A Cultural Cartography: Mapping the Enduring Legacy of Native American Jewelry Making

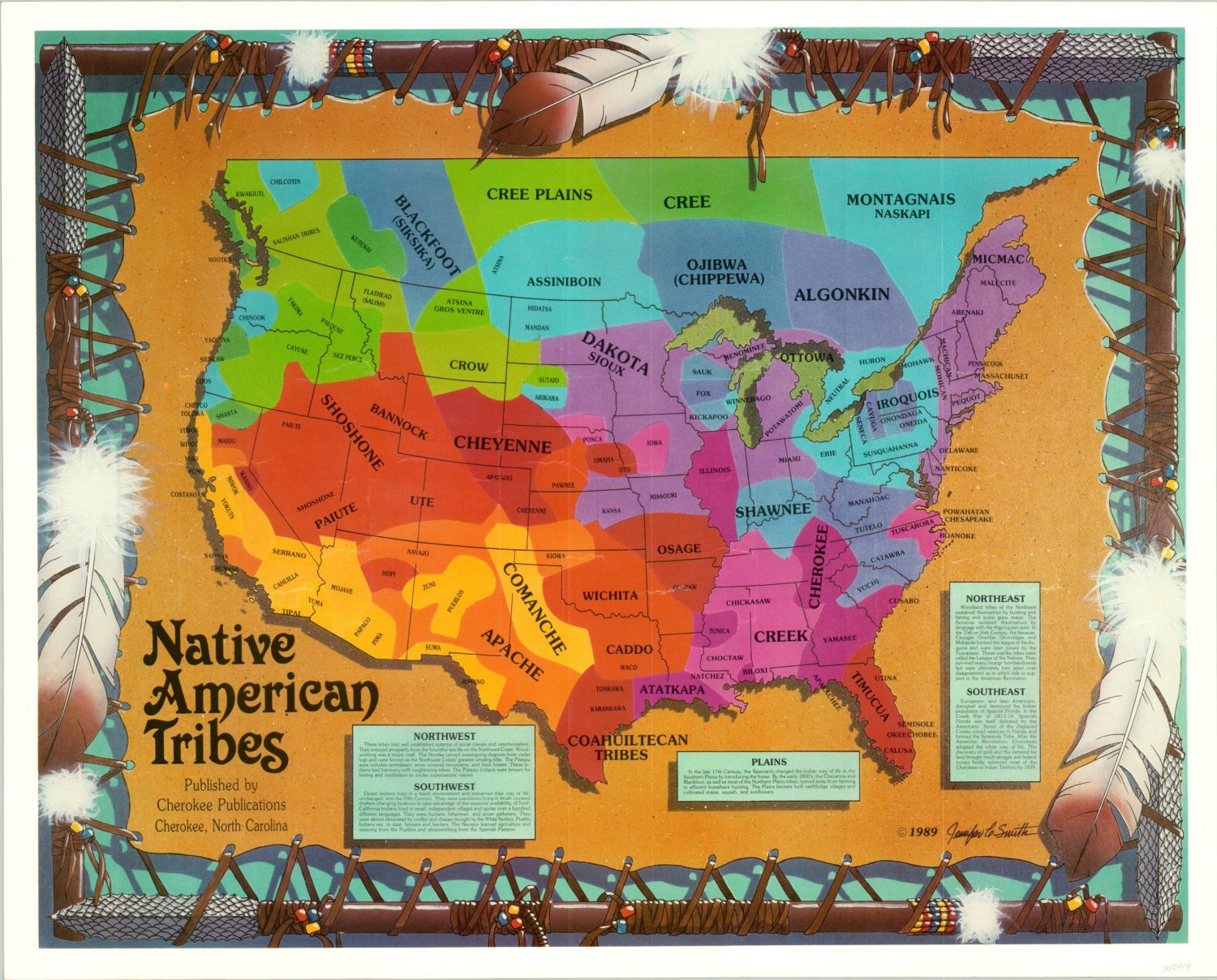

Native American jewelry is far more than mere adornment; it is a profound visual language, a tangible history, and a vibrant expression of identity etched in stone, metal, and shell. To truly appreciate its depth, one must embark on a cultural cartography, mapping the diverse tribal traditions, ancient techniques, and spiritual philosophies that have shaped this art form across the vast landscape of North America. This exploration transcends geographical boundaries, revealing an intricate tapestry woven from millennia of innovation, resilience, and sacred connection to the land.

The Deep Roots: Pre-Columbian Foundations

Before the arrival of Europeans, Indigenous peoples across the continent were sophisticated artisans, utilizing materials readily available from their environments. Jewelry served not only as personal adornment but also as markers of status, ceremonial objects, and potent symbols imbued with spiritual meaning.

In the Southwest, ancestral Puebloan peoples, including the Hohokam and Mogollon, were master carvers and grinders. They crafted intricate beads and pendants from turquoise, shell (especially conus and abalone from distant coastal trade routes), lignite, and argillite. The Hohokam, particularly, were renowned for their acid-etched shell work, a complex process involving masking and natural acids derived from plants – a testament to advanced chemical knowledge. Turquoise, even then, was highly prized, symbolizing sky, water, and protection. Necklaces of heishi beads (small, disc-shaped beads typically made from shell) were common, meticulously drilled and strung.

Further east, in the Mississippian cultures of the Southeast (e.g., Cahokia), shell gorgets (pendants) were intricately carved with motifs representing cosmology, deities, and mythological beings, often depicting bird-men, serpents, and complex ceremonial scenes. Copper, sourced from the Great Lakes region, was cold-hammered into effigies, ear spools, and repoussé plates, demonstrating advanced metallurgy.

Along the Northwest Coast, tribes like the Tlingit, Haida, and Kwakwaka’wakw utilized wood, bone, and abalone shell to create potent crest figures and transformative masks. Copper was also valued, often beaten into shield-like forms or bracelets, symbolizing wealth and status.

These early traditions laid the groundwork, establishing a deep reverence for materials and an innate understanding of how art could embody cultural narrative and spiritual power.

The Transformative Encounter: Silver and the Spanish Influence

The landscape of Native American jewelry underwent a profound transformation with the arrival of the Spanish in the 16th century. While some Indigenous cultures already possessed limited metalworking skills (primarily cold-hammering copper), the Spanish introduced sophisticated silversmithing techniques, tools, and the metal itself – often in the form of coins.

It was in the Southwest, particularly among the Navajo (Diné), that silversmithing truly blossomed. By the mid-19th century, Navajo artisans learned the craft from Mexican smiths, quickly adapting and integrating it into their own aesthetic and cultural framework. Atsidi Sani (Old Smith), often credited as the first Navajo silversmith, began working around 1850. The Navajo rapidly developed a distinct style characterized by heavy gauge silver, intricate stamping, repoussé (hammering metal from the reverse to create a raised design), and sandcasting. The squash blossom necklace, with its crescent-shaped "naja" pendant and "blossom" beads, became an iconic Navajo creation, though its origins draw from Spanish and Moorish influences. Concho belts, often adorned with stamped or repoussé silver ovals, also became quintessential Navajo pieces. Turquoise, when combined with silver, became an even more powerful symbol, embodying the union of earth and sky, protection and prosperity.

The introduction of silver was not merely an adoption of a new material; it was an act of cultural synthesis and empowerment. It provided a new medium for expressing existing spiritual beliefs, clan identities, and personal stories, and crucially, it became a vital source of economic independence.

Mapping the Major Regional Styles and Tribal Signatures

The "map" of Native American jewelry truly comes alive when examining the distinct styles that emerged from different tribal nations and geographical regions, each a unique dialect within a shared artistic language.

1. The Southwest: A Symphony of Stone and Silver

The Southwest remains the epicenter of Native American jewelry, home to diverse Pueblo tribes, the Navajo, and the Zuni, each with a recognizable signature.

-

Navajo (Diné): As mentioned, Navajo jewelry is renowned for its bold, substantial silverwork. Their pieces often feature large, natural turquoise stones, set simply to highlight the beauty of the matrix (the host rock). Techniques include heavy stamping (using hand-carved dies), sandcasting (pouring molten silver into a mold made of sand and clay), tufa casting (using volcanic tufa stone for molds), and overlay (though less common than Hopi overlay, some Navajo artists use it). Themes often draw from the natural world, spiritual concepts like Hózhó (walking in beauty), and the importance of family and community. Their work often reflects individual artistic expression and improvisation.

-

Zuni: In contrast to the Navajo’s bold simplicity, Zuni jewelry is characterized by its meticulous precision and intricate stone setting. Zuni artisans are masters of:

- Inlay: Carefully cut and fitted stones (turquoise, coral, jet, mother-of-pearl) laid into a silver channel, often forming mosaic designs or pictorial representations.

- Needlepoint and Petit Point: Tiny, elongated or round stones meticulously set to create delicate, lace-like patterns, often forming clusters or rosettes.

- Fetish Carvings: Small, animal effigies carved from stone (often turquoise, jet, or shell) and adorned with beads or tiny bundles. These are believed to embody the spirit of the animal and offer protection or guidance. Zuni jewelry often tells stories, depicts sacred animals (like the bear or badger), or represents traditional Zuni cosmology.

-

Hopi: Hopi jewelry is distinguished by its unique overlay technique. Two layers of silver are used: a bottom layer that is oxidized (blackened), and a top layer from which a design is cut out. The top layer is then soldered onto the bottom, allowing the darkened silver to show through the cut-out areas, creating a striking contrast. Hopi designs are deeply symbolic, featuring clan symbols (bear paw, eagle, cloud, corn), Katsina figures, and motifs representing the Hopi universe and their agricultural heritage. Their work is often clean, geometric, and rich in spiritual narrative.

-

Santo Domingo (Kewa) Pueblo: Known for their continuation of ancient traditions, Santo Domingo artisans excel in heishi bead making from shell (often turquoise, jet, or argillite). They also produce beautiful mosaic inlay jewelry, where small, precisely cut pieces of stone and shell are meticulously set onto a base of shell, wood, or other material, often forming geometric or animal designs. Their work often reflects a direct lineage to pre-Columbian techniques and aesthetics.

2. The Plains Tribes: Adornment of Power and Protection

For tribes of the Great Plains, such as the Lakota, Cheyenne, Crow, and Blackfeet, jewelry and personal adornment were integral to expressing identity, status, and spiritual power. While silverwork was less prominent, other materials took center stage.

- Beadwork: Post-contact, glass seed beads became a primary medium. Plains tribes developed intricate beadwork techniques like the lazy stitch and peyote stitch, creating vibrant geometric patterns and pictorial designs on buckskin, rawhide, and cloth. Beads were used to adorn everything from moccasins and dresses to pipe bags, horse regalia, and ceremonial items.

- Quillwork: Before the widespread availability of glass beads, porcupine quills were a primary decorative element. Quills were flattened, dyed, and then intricately sewn onto hide or birchbark using specific stitches (wrapping, plaiting, weaving) to create geometric patterns.

- Bone and Shell: Bone hair pipes were strung into chokers and breastplates, offering protection and signifying warrior status. Dentalium shells, acquired through extensive trade networks, were also incorporated into necklaces and ear ornaments. These pieces were not just decorative; they were often worn into battle or for important ceremonies, imbued with personal and communal significance.

3. The Northwest Coast: Narrative in Copper and Carving

The Indigenous peoples of the Northwest Coast (e.g., Haida, Tlingit, Kwakwaka’wakw) have a distinct artistic tradition characterized by complex formline design – a unique style of curvilinear shapes that depict animals, mythological beings, and ancestral crests.

- Copper and Silver: While wood carving is paramount, metalwork, particularly in copper and later silver, plays a significant role. Artists create bracelets, rings, and pendants often featuring engraved or repoussé designs of clan animals like the raven, bear, or killer whale. These pieces are not just aesthetically pleasing; they are potent symbols of family lineage, social status, and spiritual connection.

- Abalone Shell: Abalone shell, with its iridescent sheen, is frequently inlaid into wood carvings or silver pieces, adding a luminous quality to the designs.

- The jewelry reflects a deep connection to oral traditions, potlatch ceremonies, and the rich marine environment that defines their culture.

4. Great Lakes and Eastern Woodlands: Wampum and Woodland Aesthetics

Tribes like the Iroquois (Haudenosaunee), Ojibwe, and Penobscot in the Great Lakes and Eastern Woodlands regions developed distinct styles.

- Wampum: Perhaps the most iconic material is wampum, beads made from quahog (purple) and whelk (white) shells. Wampum belts were not merely decorative; they served as mnemonic devices, recording treaties, historical events, and sacred laws. They were also used in ceremonies and as currency.

- Quillwork and Beadwork: Similar to the Plains, quillwork and later glass beadwork adorned clothing, pouches, and ceremonial items, often featuring floral motifs, woodland animals, and geometric patterns unique to their regional aesthetics. The vibrant colors and intricate details spoke to their connection to the forest environment.

Identity Woven In: More Than Adornment

Across all these diverse traditions, Native American jewelry transcends its material form to become a powerful repository of identity.

- Spiritual Connection: Many stones, like turquoise, are considered sacred, connecting the wearer to the sky, water, and ancestral spirits. Fetishes embody the spirit of animals, offering protection or guidance. Designs often reflect cosmology, creation stories, and prayers.

- Cultural Resilience: Through centuries of colonization, forced assimilation, and cultural suppression, jewelry making remained a steadfast means of preserving and expressing Indigenous identity. It was a silent, yet powerful, act of cultural survival and self-determination.

- Storytelling and History: Each piece often carries a narrative – a clan history, a personal journey, a spiritual teaching. Wampum belts literally record treaties, while Hopi overlay designs depict ancestral migration paths.

- Status and Community: Historically, jewelry marked status within the community, denoted achievements, or signified membership in particular societies. Even today, heirloom pieces are passed down, connecting generations.

- Economic Empowerment: For many Native American artists, jewelry making is a vital source of livelihood, allowing them to sustain their families and communities while preserving cultural heritage. This economic independence is a crucial aspect of modern Indigenous sovereignty.

The Modern Landscape and Ethical Engagement

Today, Native American jewelry making continues to evolve. Contemporary Indigenous artists are pushing boundaries, blending traditional techniques and motifs with modern aesthetics, creating breathtaking pieces that speak to both ancient wisdom and present-day experiences. They innovate with new materials, reinterpret classic designs, and engage with global art movements, all while maintaining a profound respect for their heritage.

For the traveler and the conscious consumer, engaging with this art form demands respect and education. To truly appreciate Native American jewelry is to understand its history, its cultural significance, and the identity it embodies.

- Seek Authenticity: Learn to identify genuine Native American-made jewelry. Look for hallmarks, artist signatures, and provenance.

- Support Directly: Purchase from reputable galleries, tribal enterprises, or directly from artists at markets and festivals. This ensures that the economic benefits directly support Native communities.

- Educate Yourself: Learn about the specific tribes, their traditions, and the meanings behind the designs. Avoid generalizing all "Native American" jewelry as monolithic.

- Respect Cultural Significance: Understand that some designs or materials may hold sacred meaning and should be treated with reverence. Avoid cultural appropriation by understanding the context and not simply replicating designs without permission or understanding.

Conclusion: A Living Map of Heritage

The "map" of Native American jewelry making is not static; it is a living, breathing testament to the enduring creativity, spirituality, and resilience of Indigenous peoples. Each bead, each stamp, each carefully set stone is a marker on this cultural cartography, guiding us through millennia of history, revealing the profound identities of countless nations, and inviting us to connect with a heritage that is as rich and diverse as the land itself. To wear or collect Native American jewelry is to carry a piece of this extraordinary journey, a tangible link to a world where art, history, and identity are inextricably bound. It is an invitation to learn, to respect, and to celebrate an artistic legacy that continues to inspire and enrich the world.