The Living Map: Infrastructure as a Tapestry of Native American Sovereignty and Identity

Beyond the static lines of reservation boundaries or the often-incomplete historical maps, a dynamic and evolving "map" of Native American infrastructure projects tells a profound story. It is a narrative not just of concrete, steel, and fiber optics, but of enduring sovereignty, cultural revitalization, and self-determination. For travelers seeking deeper understanding and for students of history, this living map offers an unparalleled lens into the resilience and future vision of tribal nations across North America. This article delves into how infrastructure development on Native lands is inextricably linked to their history, identity, and the ongoing assertion of their inherent rights, making it a compelling subject for both educational and experiential exploration.

The Historical Landscape: Seeds of Underdevelopment

To truly appreciate the significance of contemporary Native American infrastructure, one must first understand the historical context that necessitated its urgent development. Prior to European contact, Indigenous nations maintained sophisticated infrastructure: vast trade networks, intricate irrigation systems, well-planned settlements, and sustainable resource management practices. However, centuries of colonization systematically dismantled these systems, replacing them with policies designed for displacement, assimilation, and control.

The post-colonial era, particularly following the reservation period, saw federal policies that actively stifled tribal development. Lands were often assigned in remote, resource-poor areas. Treaties, though legally binding, were frequently violated, leading to land loss and economic disenfranchisement. Federal "trust responsibility" often translated into paternalistic oversight rather than genuine investment. The Dawes Act of 1887 broke up communal lands, further eroding tribal economic bases. The "termination era" of the mid-20th century sought to dissolve tribal governments and assimilate Native peoples, resulting in catastrophic losses of land, resources, and social services.

The cumulative effect of these policies was devastating. By the late 20th century, many Native American communities faced chronic underdevelopment: dilapidated housing, unpaved roads, limited access to clean water and sanitation, non-existent broadband, and inadequate healthcare and educational facilities. These conditions were not accidental; they were the direct legacy of systemic neglect and deliberate suppression of tribal self-sufficiency. Thus, every new road, every water treatment plant, and every fiber optic cable laid on tribal land today is not merely an amenity but a direct act of reclaiming what was lost and building a future on their own terms.

Infrastructure as an Assertion of Sovereignty

The modern era of tribal self-determination, ushered in by legislation like the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975, marked a pivotal shift. Tribes began to assert their inherent sovereign right to govern themselves, manage their resources, and plan for their own futures, rather than passively receiving federal services. Infrastructure development became a powerful tool in this assertion.

When a tribal government builds a new road, it’s not just connecting two points; it’s demonstrating its capacity to govern and provide for its citizens. When a tribe establishes its own broadband network, it’s not just closing the digital divide; it’s asserting control over vital communications infrastructure within its borders. This is the essence of sovereignty in action – the power to define, design, and implement solutions that meet the unique needs and cultural values of their communities.

Federal programs, such as the Tribal Transportation Program (TTP) and funding through the Indian Health Service (IHS) and the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), have become crucial pathways for these projects. However, the impetus and direction overwhelmingly come from tribal governments, who prioritize projects based on community needs, cultural significance, and long-term economic development goals, rather than external mandates.

Key Infrastructure Sectors: Building the Future, Preserving the Past

The "map" of Native American infrastructure projects is multifaceted, covering essential sectors that address both immediate needs and long-term aspirations.

1. Transportation: The Arteries of Opportunity

Poor road conditions have historically isolated many tribal communities, hindering access to jobs, education, healthcare, and emergency services. The construction and maintenance of roads and bridges on tribal lands are therefore critical. Projects range from paving unpaved reservation roads to building modern highway connections, facilitating commerce, tourism, and community cohesion. For example, improved roads allow tribal members to access jobs outside the reservation, bring goods to market, and ensure that cultural events are accessible to all. These roads often trace ancestral paths, symbolically reconnecting communities to their traditional territories.

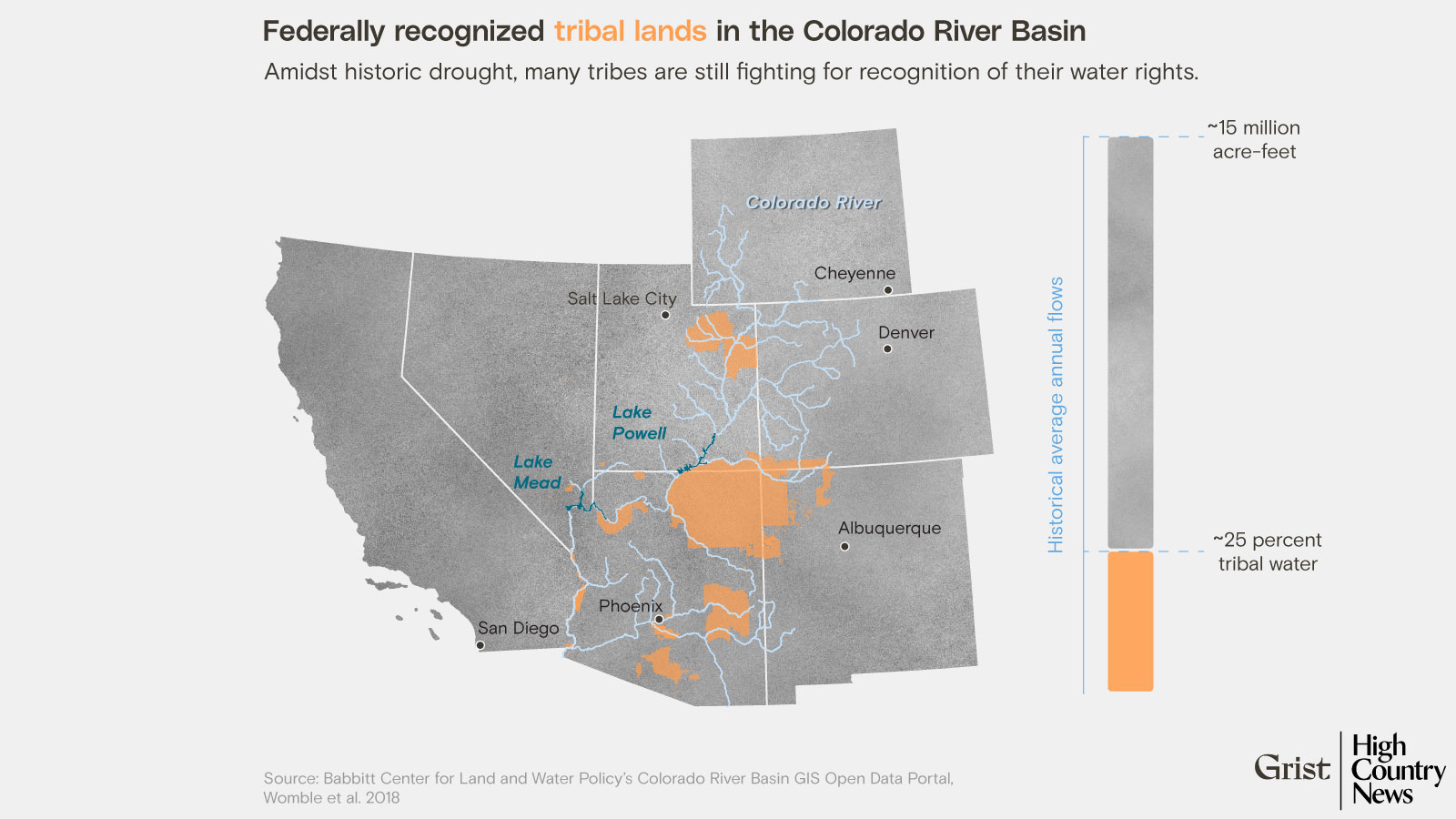

2. Water and Sanitation: Health, Environment, and Sacred Trust

Access to clean, safe drinking water and adequate sanitation systems remains a pressing issue for many Native communities, a stark reminder of historical neglect. Infrastructure projects in this sector – including new water treatment plants, well drilling, pipeline construction, and wastewater management systems – are fundamental to public health and environmental justice. Many tribes are also investing in traditional water management techniques, blending indigenous knowledge with modern technology to ensure sustainable water resources, reflecting a deep cultural reverence for water as a sacred element. Projects like the Navajo-Gallup Water Supply Project illustrate massive undertakings to bring reliable water to thousands of homes.

3. Broadband and Digital Inclusion: Bridging the Divide

In the 21st century, internet access is not a luxury but a necessity for education, healthcare (telehealth), economic development, and civic engagement. Many remote tribal lands have been historically underserved by commercial providers due to perceived low profitability. Consequently, tribes are taking matters into their own hands, building their own fiber optic networks and wireless infrastructure. These projects are not just about connectivity; they are about digital sovereignty, enabling tribal schools to offer online learning, facilitating tribal businesses to reach global markets, and allowing tribal governments to deliver services more efficiently. This digital infrastructure is crucial for preserving Native languages and cultures through online resources and virtual community spaces.

4. Energy Independence and Renewable Projects: Stewardship and Self-Sufficiency

Native nations are increasingly leading the way in renewable energy development. Projects like solar farms on tribal lands (e.g., the Moapa Band of Paiutes’ solar plant) and wind energy initiatives not only provide clean, sustainable power but also generate significant revenue for tribal governments, creating jobs and fostering energy independence. This commitment to renewable energy often aligns deeply with traditional Indigenous values of environmental stewardship and respect for Mother Earth, offering a powerful example of how modern development can harmonize with ancestral wisdom.

5. Housing and Community Facilities: Building Homes, Nurturing Identity

Addressing chronic housing shortages and dilapidated conditions is a priority for many tribes. New housing developments, often designed with cultural considerations in mind, provide safe and stable homes. Beyond housing, tribes are investing in community centers, schools (many offering language immersion programs), healthcare clinics, and cultural preservation centers. These facilities are vital for fostering community cohesion, preserving language and traditions, and ensuring the well-being of tribal members from infancy through elderhood. A new school built with a traditional architectural style, for instance, reinforces cultural identity with every lesson taught within its walls.

The "Map" as a Narrative of Resilience and Vision

The aggregated "map" of these diverse infrastructure projects forms a powerful, multi-layered narrative. It’s a testament to:

- Resilience: Each project represents overcoming centuries of adversity, underdevelopment, and neglect. It’s a defiant statement against the forces that sought to erase Native cultures and economies.

- Cultural Preservation: From schools teaching ancestral languages to community centers hosting traditional ceremonies, infrastructure directly supports the revitalization and transmission of cultural heritage. High-speed internet allows for digital archives of oral histories and language lessons to reach a wider audience, even those off-reservation.

- Economic Self-Sufficiency: Infrastructure is the bedrock of economic development. Improved transportation, reliable utilities, and digital connectivity attract investment, support tribal enterprises, and create jobs, allowing tribes to build robust economies that benefit their members.

- Environmental Stewardship: Many infrastructure projects, particularly in water management and renewable energy, are guided by Indigenous principles of sustainability and respect for the natural world, offering models for responsible development.

- Intergenerational Vision: These projects are not just for today; they are built with future generations in mind. They represent a long-term commitment to improving quality of life, ensuring access to resources, and strengthening the foundation for continued tribal sovereignty and cultural flourishing.

For a traveler or an educator, understanding this "map" means looking beyond the physical structures to grasp the profound meaning embedded within them. A highway through a reservation isn’t just asphalt; it’s a path to opportunity forged by tribal determination. A solar farm isn’t just an energy source; it’s an expression of environmental wisdom and economic independence.

Challenges and the Path Forward

Despite significant progress, Native American infrastructure development still faces considerable challenges. Funding remains a persistent hurdle, as federal programs, while helpful, often fall short of the immense needs. Bureaucratic complexities, jurisdictional issues between tribal, state, and federal governments, and the impacts of climate change (e.g., extreme weather damaging existing infrastructure) further complicate efforts.

However, the opportunities are equally vast. The recent Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (IIJA) in the United States, for example, has earmarked substantial funding for tribal infrastructure, offering an unprecedented chance to accelerate development. Tribal ingenuity, coupled with strategic partnerships and the leveraging of traditional ecological knowledge, continues to drive innovative solutions.

Conclusion: A Living Legacy

The "Map of Native American Infrastructure Projects" is more than a geographical representation; it is a living document, constantly being drawn and redrawn by the hands of tribal nations. It is a powerful illustration of how communities, rooted in deep history and strong identity, are actively shaping their futures. For anyone interested in the true narrative of North America, this map offers essential insights into the ongoing journey of Indigenous peoples – a journey of resilience, self-determination, and a profound commitment to building a better world, one project at a time. To witness these developments, to understand their context, and to appreciate their profound significance is to engage with a vital and inspiring chapter of American history and its unfolding future.