Echoes of the Hunt: Unearthing the Rich Tapestry of Native American Hunting Grounds

When we speak of "hunting grounds" in the context of Native American history, we are not merely discussing geographical areas where game was pursued. We are delving into a profound and intricate concept that lies at the heart of identity, spirituality, governance, and survival for countless indigenous nations across North America. Far from static, two-dimensional lines on a colonial map, these territories were dynamic, living landscapes, interwoven with a worldview that fostered deep respect and reciprocity with the natural world. For the modern traveler and history enthusiast, understanding these historical hunting grounds offers a vital lens through which to appreciate the true depth of Native American cultures, their resilience, and their enduring connection to the land.

More Than Just Terrain: The Holistic View of Hunting Grounds

The European concept of land ownership, often based on fixed boundaries and individual deeds, was alien to most Native American peoples. Instead, their relationship with the land was communal, spiritual, and utilitarian in a holistic sense. Hunting grounds were not merely resource extraction zones; they were ancestral homelands, sacred sites, burial grounds, and places where entire cosmologies were lived out.

For tribes like the Lakota on the Great Plains, their vast hunting grounds, stretching across what is now Nebraska, South Dakota, Wyoming, and Montana, were defined by the migrations of the bison. These enormous herds were not just food; they provided hides for shelter and clothing, bones for tools, and sinew for thread. The bison was a spiritual relative, a gift from the Creator, and its presence dictated movement, ceremony, and social structure. To map these grounds was to map the heartbeat of the nation, a constantly shifting canvas reflecting seasonal cycles and the availability of resources.

Similarly, in the Eastern Woodlands, nations such as the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois Confederacy) or the Cherokee understood their hunting territories as part of a larger, managed ecosystem. Deer, bear, turkey, and smaller game were vital, but so were forests for timber and nuts, rivers for fish, and clearings for agriculture. Their "hunting grounds" often overlapped with agricultural lands, demonstrating a sophisticated system of land use that balanced resource extraction with conservation and replenishment. These were not pristine wildernesses untouched by human hands, but rather meticulously managed landscapes, shaped by generations of intentional burning, planting, and harvesting to enhance biodiversity and ensure future abundance.

The Elusive Map: Reconstructing a Dynamic Reality

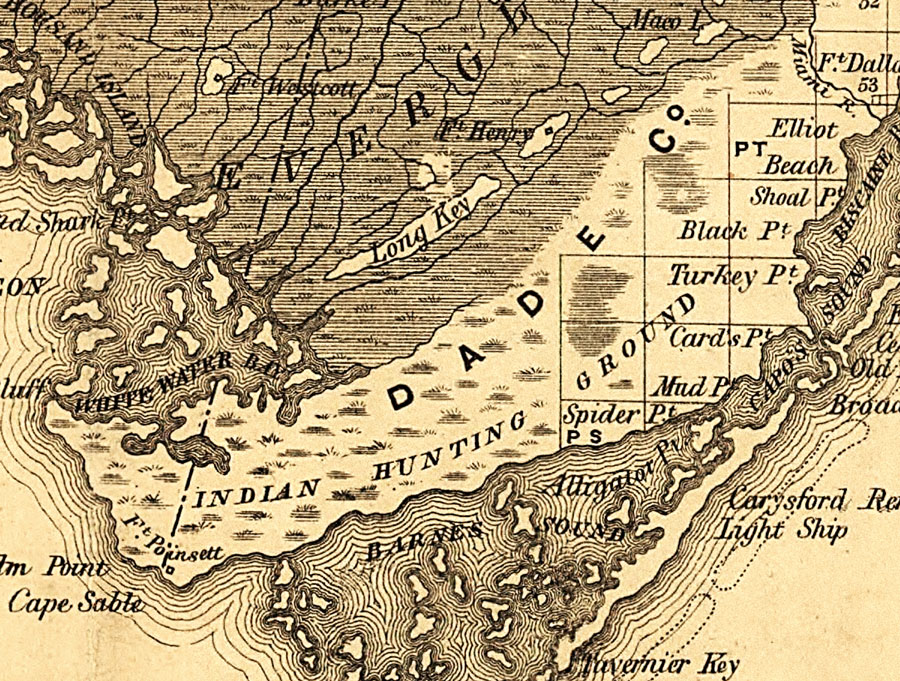

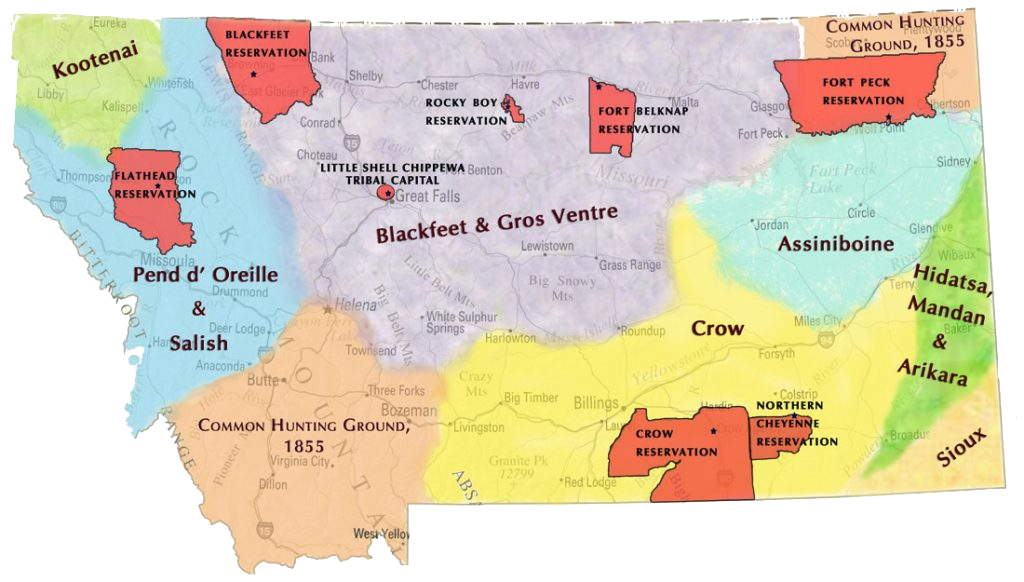

Creating a definitive "Map of Native American Hunting Grounds" is a complex, almost paradoxical endeavor. Pre-contact, most indigenous societies did not use cartographic systems akin to European maps. Their knowledge of territory was embodied in oral traditions, songs, stories, and the lived experience of generations. Boundaries were often fluid, defined by geographical features, seasonal movements, and shared understandings rather than rigid lines.

Furthermore, many hunting grounds were shared territories, utilized by multiple tribes under agreements of coexistence or through periods of contestation. For example, the Ohio Valley was often referred to as a "common hunting ground" by various Algonquin and Iroquoian-speaking groups, a place of both shared resources and occasional conflict. A single tribe’s territory might expand or contract based on military strength, political alliances, or ecological shifts.

Modern maps attempting to depict these historical hunting grounds are therefore reconstructions, often based on colonial records, treaty documents, and archaeological evidence, cross-referenced with surviving oral histories. They are invaluable tools for understanding the scale and scope of indigenous land use, but they can never fully capture the dynamic, spiritual, and deeply personal connection each nation had to its specific ancestral lands. These maps are interpretations, not immutable truths, and they serve as a starting point for deeper inquiry, rather than a definitive statement.

A Continent of Diverse Ecosystems and Adaptations

The sheer diversity of North America meant that hunting grounds varied dramatically from region to region, reflecting distinct ecological adaptations:

-

The Great Plains: Dominated by the bison, these vast grasslands were the domain of nomadic and semi-nomadic tribes like the Lakota, Cheyenne, Comanche, and Crow. Their hunting grounds followed the herds, necessitating mobility and highly organized communal hunts. The introduction of the horse by Europeans revolutionized their hunting practices, allowing for more efficient pursuit and the expansion of territories.

-

The Eastern Woodlands: From the Great Lakes down to the Southeast, dense forests, rivers, and lakes characterized the hunting grounds of tribes such as the Lenape, Algonquin, Cherokee, and Choctaw. Deer, bear, turkey, and fish were primary resources. Hunting was often a solitary or small-group endeavor, complemented by extensive agriculture (corn, beans, squash). Seasonal camps were common, moving between river valleys, upland forests, and coastal areas to exploit different resources.

-

The Southwest: Arid lands and desert environments presented unique challenges. Tribes like the Apache, Navajo, and various Pueblo peoples adapted their hunting grounds to scarce water sources and sparse game (deer, bighorn sheep, rabbit). While hunting was important, particularly for nomadic groups like the Apache, agriculture (Pueblo) and pastoralism (Navajo, post-contact) played significant roles in their subsistence strategies.

-

The Pacific Northwest: Abundant salmon runs defined the hunting and fishing grounds of coastal tribes such as the Haida, Tlingit, and Kwakwaka’wakw. Their territories included vast stretches of coastline, rivers, and dense forests where deer, bear, and marine mammals were hunted. The rich resources allowed for complex, settled societies with elaborate social structures and art forms.

-

The Arctic and Subarctic: For groups like the Inuit and Dene, hunting grounds were vast, frozen expanses where caribou, seal, whale, and polar bear were essential for survival. These territories were often immense, requiring extensive knowledge of migration patterns, ice conditions, and animal behavior.

Each region’s hunting grounds were a testament to generations of accumulated ecological knowledge, sophisticated land management, and a deep understanding of the natural world.

The Cataclysm of Contact: Disruption and Dispossession

The arrival of Europeans brought catastrophic changes to Native American hunting grounds. Initially, the fur trade, driven by European demand for beaver pelts and other furs, dramatically altered indigenous hunting practices. Tribes, incentivized by European goods like metal tools, firearms, and alcohol, often intensified their hunting efforts, sometimes leading to over-trapping in certain areas. This economic shift introduced a market economy that disrupted traditional subsistence patterns and fostered new rivalries among tribes for control of prime trapping territories.

However, the more devastating impact came from disease and land hunger. European diseases, against which Native Americans had no immunity, decimated populations, sometimes by as much as 90%. This weakened tribal resistance and left vast areas seemingly "empty" to European eyes, despite millennia of indigenous habitation and use.

As colonial settlements expanded, the concept of "unoccupied land" became a convenient justification for appropriation. Treaties, often poorly understood by Native signatories, fraudulently negotiated, or simply broken, systematically chipped away at ancestral hunting grounds. The "Indian Removal Act" of 1830, for instance, forcibly relocated numerous southeastern tribes (Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole) from their ancestral lands and hunting grounds to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma), a traumatic event known as the Trail of Tears. This act was a blatant disregard for established treaties and millennia of cultural and spiritual connection to specific landscapes.

The relentless westward expansion of the United States, fueled by Manifest Destiny, further encroached upon hunting grounds, particularly on the Great Plains. The systematic slaughter of the bison, driven by both market demand and a deliberate strategy to starve and subdue the Plains tribes, effectively destroyed the foundation of their traditional way of life and sovereignty. By the late 19th century, millions of bison had been reduced to a few hundred, and the vast hunting grounds that sustained entire nations lay desolate.

The Enduring Legacy: Hunting Grounds in the Modern Era

Today, the concept of Native American hunting grounds continues to resonate deeply. While most traditional hunting grounds have been lost to private ownership, state parks, national forests, and urban development, the memory and significance of these lands persist.

Many contemporary Native American nations are actively engaged in reclaiming, protecting, and revitalizing their ancestral lands and resources. This includes:

- Treaty Rights: Many treaties, though often violated, still enshrine specific hunting, fishing, and gathering rights on ancestral lands, even those outside current reservation boundaries. These rights are continually litigated and defended, representing a crucial aspect of tribal sovereignty and cultural preservation.

- Land Back Movement: This ongoing initiative seeks to return ancestral lands to indigenous stewardship, recognizing that Native American communities are often the best conservators of these ecosystems, drawing on millennia of traditional ecological knowledge.

- Cultural Revitalization: Hunting, fishing, and gathering remain vital cultural practices for many Native Americans, connecting younger generations to their heritage, traditional foodways, and spiritual beliefs. Efforts are made to teach traditional hunting methods, language, and ceremonies associated with these practices.

- Environmental Stewardship: Native American nations are at the forefront of conservation efforts, applying traditional ecological knowledge to manage forests, restore rivers, and protect endangered species. They understand that healthy ecosystems are intrinsically linked to cultural health and self-determination.

The maps we study today, showing historical hunting grounds, are not merely relics of the past. They are powerful reminders of a profound connection to land that predates colonial borders. They illustrate the vastness of indigenous knowledge systems, the resilience of cultures in the face of immense adversity, and the ongoing struggle for self-determination and environmental justice.

Beyond the Lines: Identity, Spirituality, and the Land

Ultimately, understanding Native American hunting grounds transcends the lines on any map. It is about comprehending a worldview where the land is not merely property but a relative, a teacher, and a source of life. It is about acknowledging the intricate web of relationships – between humans and animals, between present generations and ancestors, between the physical and spiritual realms – that defined existence for centuries.

For the travel blogger and history enthusiast, this understanding offers an opportunity to engage with places in a deeper, more respectful way. When visiting national parks, wilderness areas, or even urban centers, recognizing that these were once vibrant hunting grounds, imbued with history, ceremony, and the daily lives of indigenous peoples, transforms the experience. It invites us to look beyond the superficial, to listen for the echoes of the hunt, and to appreciate the enduring identity forged in these lands. By doing so, we not only honor the past but also gain invaluable insights into sustainable living, cultural resilience, and the universal human quest for belonging to a place.