The Living Map: Navigating Native American Human Rights Advocacy

Forget static lines on paper. The "Map of Native American Human Rights Advocacy" is not a cartographic artifact you can unfurl; it is a dynamic, multi-layered tapestry woven from centuries of struggle, resilience, and unwavering commitment to justice. For anyone seeking a deeper understanding of North American history, identity, and the ongoing fight for fundamental rights, this conceptual map offers an essential, often overlooked, lens. It charts the interconnected geographies of land, sovereignty, culture, and human dignity, revealing how Indigenous peoples across the continent have continuously asserted their rights against immense odds. This is a map for the curious traveler and the dedicated historian alike, inviting engagement with the vibrant, complex realities of Native nations today.

The Deep Roots of Advocacy: A Historical Imperative

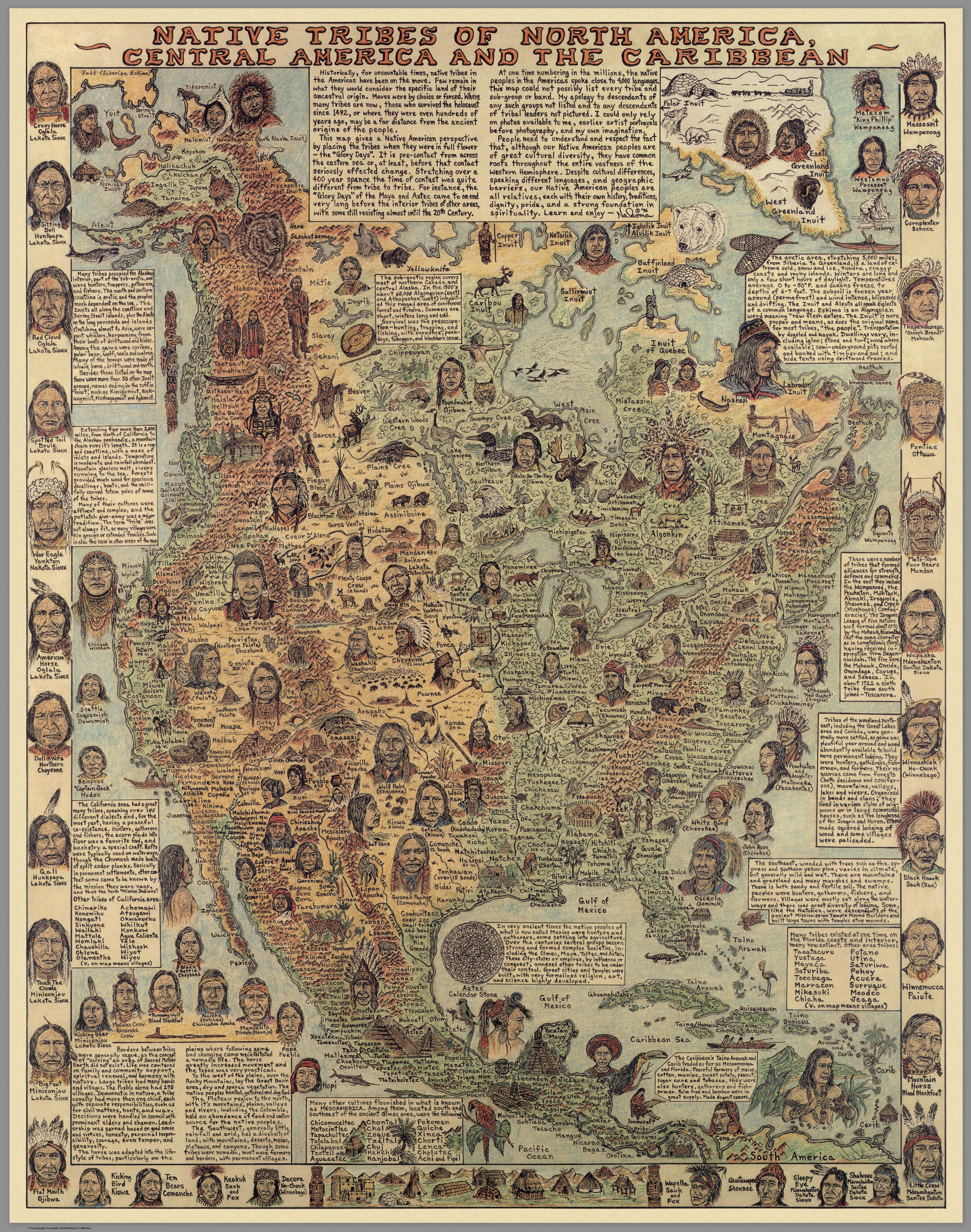

To understand contemporary Native American human rights advocacy, one must journey back to its origins – a history not of petitioning for rights, but of defending inherent sovereignty and existence. Before European contact, hundreds of distinct Indigenous nations thrived, each with intricate governance systems, economies, and spiritual practices. The arrival of European powers marked an immediate shift from sovereign self-determination to a prolonged battle for survival.

Early forms of advocacy were direct and often martial: defending ancestral lands, resisting forced conversion, and negotiating treaties that, while often broken by the colonizers, were themselves acts of diplomatic engagement between sovereign entities. Figures like Pontiac, Tecumseh, and Metacom (King Philip) were not merely war chiefs but formidable political leaders advocating for their people’s future.

The formation of the United States brought a new, systematic challenge. The Indian Removal Act of 1830, leading to the forced relocation of the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole nations along the "Trail of Tears," epitomizes the egregious human rights violations that necessitated organized advocacy. Even as communities were shattered, legal battles, such as Worcester v. Georgia (1832), demonstrated early attempts to use the colonizer’s own legal framework to assert Indigenous rights, even if the ruling was largely ignored.

The late 19th and early 20th centuries saw a concerted effort by the U.S. government to assimilate Native peoples. Policies like the Dawes Act (1887) aimed to break up communal landholdings into individual allotments, destroying tribal economies and governance structures. Simultaneously, the boarding school era forcibly removed Indigenous children from their families, banning their languages and cultural practices in a deliberate act of cultural genocide. It was during this period that the first pan-tribal organizations began to emerge, such as the Society of American Indians (founded 1911), which sought to advocate for Native interests within the dominant society’s political system.

The mid-20th century witnessed another assault on tribal sovereignty with the "Termination Era" (1950s-1960s), which sought to dismantle tribal governments and assimilate Native Americans into mainstream society, often leading to devastating poverty and loss of services. This era, coupled with federal relocation programs that moved Native people to urban centers, inadvertently sparked a new wave of pan-tribal activism. The National Congress of American Indians (NCAI), founded in 1944, became a pivotal voice, advocating for tribal sovereignty and self-determination.

By the 1960s and 70s, the civil rights movement provided a template and inspiration for Native American activists. The American Indian Movement (AIM), founded in 1968, brought a more confrontational approach, engaging in direct action, occupations (like Alcatraz and Wounded Knee), and public protests to draw attention to treaty violations, systemic injustice, and the need for self-determination. This period solidified the foundation for modern Native American human rights advocacy, shifting the narrative from assimilation to self-governance and the assertion of inherent rights.

Geographies of Struggle and Resilience: The Living Map in Action

The conceptual "Map of Native American Human Rights Advocacy" manifests in countless specific struggles and triumphs across the continent. It’s a mosaic of localized battles that collectively illustrate the overarching themes of Indigenous rights.

Land and Resource Rights: At the heart of Indigenous identity and survival is the land. The fight for land and resource rights is a central pillar of advocacy. The Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) protests at Standing Rock (2016-2017) became a global symbol of Indigenous environmental justice, highlighting the violation of treaty rights, the protection of sacred sites, and the disproportionate impact of fossil fuel infrastructure on Native communities. This struggle, led by the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe and supported by hundreds of other tribes and allies, demonstrated the power of collective action in defending ancestral lands and water.

Similarly, the fight to protect sacred sites like Bears Ears National Monument in Utah (a coalition of five tribes) or Oak Flat in Arizona (San Carlos Apache and others) from mining or development underscores the deep spiritual and cultural connection Indigenous peoples have to their territories. Water rights, particularly in the arid American West, are another critical area of advocacy, with tribes like the Navajo, Hopi, and various Pueblo nations constantly battling to secure their rightful share of water for their communities and traditional lifeways. These struggles aren’t just about resources; they are about cultural survival and the ability to practice traditional ways of life.

Sovereignty and Self-Determination: Advocacy for sovereignty means asserting the inherent right of Native nations to govern themselves. This manifests in various ways:

- Tribal Courts and Law Enforcement: Strengthening tribal justice systems to exercise jurisdiction over their territories and people.

- Economic Development: Tribes leveraging their sovereign status to pursue economic ventures, most notably gaming, to fund essential services and create jobs for their communities, often against significant political opposition.

- Treaty Enforcement: Ongoing legal battles to uphold treaty obligations, such as fishing and hunting rights in the Pacific Northwest, or land claims across the country. The Boldt Decision (1974) affirmed the fishing rights of tribes in Washington State, setting a precedent for treaty-based resource co-management.

- Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA): This landmark 1978 federal law, passed in response to the alarmingly high rates of Native children being removed from their homes and placed into non-Native foster or adoptive families, asserts tribal jurisdiction over child welfare cases. It is a vital tool for protecting Native families and cultural continuity, though it remains under constant legal threat.

Cultural Preservation and Identity: The historical attempts to erase Indigenous cultures have given rise to powerful advocacy for their revitalization.

- Language Revitalization: Efforts to preserve and teach endangered Indigenous languages, such as the Navajo Nation’s language immersion programs or the Wampanoag Language Reclamation Project, are critical to cultural survival and identity.

- Repatriation: The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) of 1990 mandated the return of Native American human remains, funerary objects, sacred objects, and objects of cultural patrimony from federal agencies and museums to lineal descendants and culturally affiliated Native American tribes. Advocacy ensures the full implementation and enforcement of this crucial law.

- Education: Advocacy for culturally relevant education, the establishment of tribal colleges and universities, and the inclusion of accurate Native American history in mainstream curricula are vital for shaping identity and empowering future generations.

- Art and Storytelling: Indigenous artists, writers, and performers use their platforms to reclaim narratives, challenge stereotypes, and affirm Indigenous identity and worldviews, acting as powerful cultural advocates.

Social Justice Issues: Native American communities face unique and often severe social justice challenges, demanding specific advocacy efforts.

- Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women (MMIW): The MMIW movement highlights the epidemic of violence against Indigenous women, girls, and Two-Spirit people, advocating for greater awareness, improved data collection, and systemic changes in law enforcement and justice systems.

- Healthcare Disparities: Decades of underfunding of the Indian Health Service (IHS) have led to severe health disparities. Advocacy pushes for adequate funding, culturally competent care, and tribal control over healthcare delivery.

- Voting Rights: Indigenous communities often face unique barriers to voting, including geographical isolation, lack of consistent mail delivery, and discriminatory ID laws. Advocacy works to ensure equitable access to the ballot box.

Key Organizations and the Global Reach of Advocacy

Populating this living map are numerous organizations, both historical and contemporary, that have driven and continue to drive Native American human rights advocacy. Beyond the NCAI and AIM, groups like the Native American Rights Fund (NARF), founded in 1970, have been instrumental in using legal strategies to protect tribal sovereignty, natural resources, and human rights. The Indigenous Environmental Network (IEN) connects Indigenous communities globally in the fight for environmental justice, linking land defense with human rights. Organizations like Women of All Red Nations (WARN) and the National Indian Youth Council (NIYC) have provided platforms for specific demographics within the broader movement.

Moreover, Native American human rights advocacy extends beyond national borders. Indigenous leaders have consistently brought their concerns to international forums, playing a crucial role in the development and adoption of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) in 2007. This declaration, though non-binding, provides a universal framework for the minimum standards for the survival, dignity, and well-being of Indigenous peoples worldwide, offering a powerful tool for advocacy at both national and international levels.

The Indispensable Role of Identity in Advocacy

The strength of Native American human rights advocacy is inextricably linked to identity. "Native American" is an umbrella term encompassing hundreds of distinct tribal nations, each with its unique history, language, spiritual practices, and governance. Advocacy is rarely monolithic; it is deeply rooted in these specific tribal identities. The resilience of these identities, despite centuries of assimilationist policies, is a testament to the enduring spirit of Indigenous peoples.

For many, identity is not merely a matter of heritage but a living connection to ancestors, land, and culture. It is this profound connection that fuels the determination to protect sacred sites, revitalize languages, and assert sovereignty. Youth engagement is particularly vital, with young Indigenous leaders leveraging social media and new technologies to amplify their voices, educate others, and continue the legacy of their elders, ensuring that the map of advocacy continues to expand and evolve.

Engaging with the Map: Travel and Education

For those interested in history, culture, and responsible travel, understanding this "Map of Native American Human Rights Advocacy" is paramount. It transforms passive observation into active learning and respectful engagement.

Responsible Tourism: When traveling through Native lands or visiting cultural sites, visitors should prioritize responsible tourism. This means:

- Respecting Sovereignty: Understanding that tribal nations are sovereign entities with their own laws and customs.

- Seeking Permission: Not entering private or sacred lands without explicit permission.

- Supporting Native Economies: Purchasing authentic Native art and crafts directly from artists or tribal enterprises, dining at Native-owned restaurants, and staying at tribally owned accommodations, thereby contributing directly to community well-being.

- Learning Before You Go: Researching the history and culture of the specific tribe whose lands you are visiting.

Learning Opportunities: Travel offers unparalleled opportunities to engage with authentic Native voices and perspectives.

- Tribal Museums and Cultural Centers: These institutions, often tribally run, offer invaluable insights into history, art, and contemporary life, challenging prevalent stereotypes.

- Powwows and Cultural Events: Attending public powwows (with an understanding of proper etiquette) can be a vibrant way to experience Native culture, dance, and community.

- Listening and Learning: Engaging with Indigenous guides, elders, and community members with an open mind and a willingness to listen.

By actively seeking out and supporting Native voices, travelers can contribute to a more accurate and respectful understanding of history, moving beyond the often-problematic narratives found in mainstream textbooks. This educational journey challenges visitors to confront uncomfortable truths about colonization while celebrating the incredible resilience, innovation, and cultural richness of Native nations.

Conclusion: An Ongoing Journey for Justice

The "Map of Native American Human Rights Advocacy" is not a historical artifact to be archived, but a living, breathing testament to the ongoing journey for justice. It charts the unwavering commitment of Indigenous peoples to their lands, their cultures, their sovereignty, and their inherent human dignity. From the ancient defense of homelands to modern battles for environmental justice and cultural revitalization, this map reveals a continuous, evolving struggle.

For anyone seeking a comprehensive understanding of the continent’s history and its future, engaging with this map is essential. It demands a recognition of past injustices, an appreciation for enduring resilience, and an active commitment to supporting the self-determination of Native nations. By understanding the deep historical roots and the contemporary expressions of Native American human rights advocacy, we can all contribute to a more just, equitable, and respectful future, honoring the original inhabitants and stewards of these lands.