The Unseen Map: Protecting Native American Genetic Resources, History, and Identity

The concept of a "map" often conjures images of lines on paper, delineating territories and charting routes. But for Native American communities, the map of genetic resources is far more profound, complex, and deeply intertwined with their history, identity, and sovereignty. This isn’t just about geographical boundaries; it’s about the very fabric of life – human, plant, animal, and microbial – that has co-evolved with Indigenous peoples on this continent for millennia. Understanding this intricate "unseen map" is crucial for anyone interested in responsible travel, historical education, and the ongoing struggle for Indigenous rights and self-determination.

Beyond Borders: What is the "Map" of Genetic Resources?

When we speak of a "Map of Native American genetic resources protection," we are not talking about a single, static document. Instead, it’s a conceptual framework encompassing several layers:

- Ancestral Lands and Territories: The most fundamental layer. For Native American tribes, land is not merely property; it is a relative, a source of identity, spirituality, and sustenance. The biodiversity within these traditional territories, from medicinal plants to unique crop varieties and specific animal populations, represents a vast repository of genetic information. This connection means that the protection of genetic resources inherently involves the protection of land rights and ecological integrity.

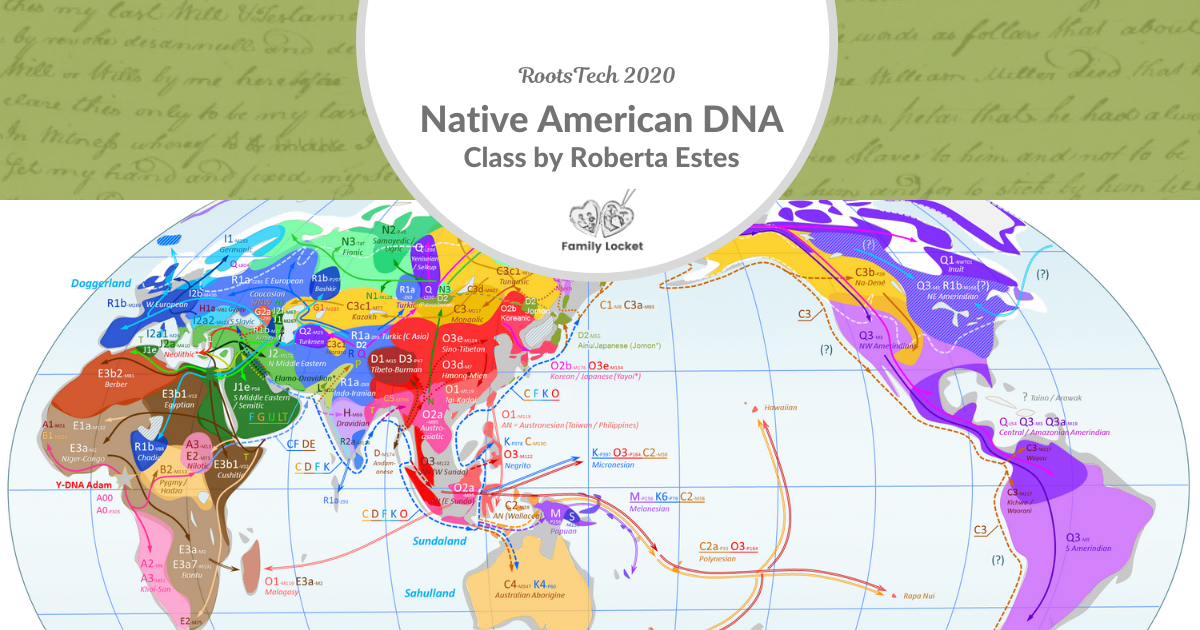

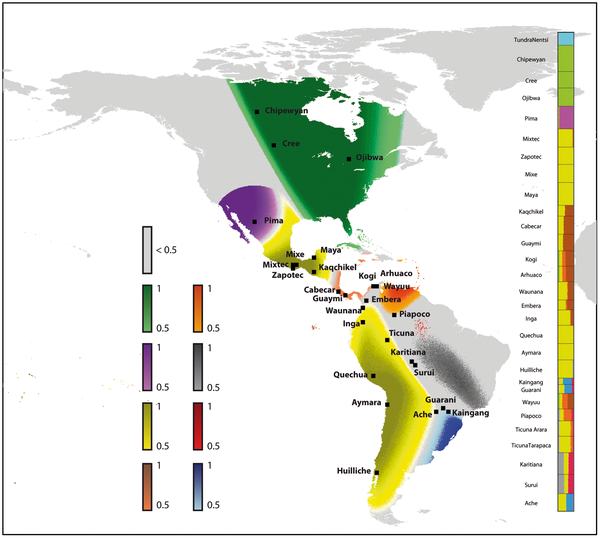

- Human Genetic Diversity: The genetic makeup of Native American peoples themselves. Each tribe possesses unique genetic markers, reflecting ancient migrations, adaptations to specific environments, and the deep histories of their communities. This human genetic diversity is inseparable from their identity, ancestry, and cultural narratives.

- Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK): This isn’t genetic material itself, but it’s the indispensable "key" to understanding and utilizing these resources. TEK comprises generations of cumulative knowledge, practices, and beliefs concerning the relationships of living beings (including humans) with their environment. It details the properties of medicinal plants, the cultivation techniques for heirloom crops, the sustainable management of forests and waters, and the spiritual significance of various species. Without TEK, much of the genetic resource map would remain indecipherable.

- Cultural Landscapes: Beyond mere physical territory, this refers to areas imbued with cultural and spiritual significance, often containing specific plants or animals central to ceremonies, diets, or traditional crafts. The genetic resources found within these landscapes are therefore also culturally irreplaceable.

This multi-layered map highlights that protecting genetic resources for Native Americans is not a purely scientific endeavor; it is a profound act of cultural preservation, historical justice, and the affirmation of Indigenous sovereignty.

A Legacy of Exploitation: The Historical Context

To appreciate the urgency of genetic resource protection, one must understand the historical backdrop of dispossession and exploitation that Native American tribes have endured.

Pre-Colonial Abundance and Stewardship: Before European contact, Indigenous peoples were sophisticated stewards of the land, developing vast agricultural systems (like the "Three Sisters" – corn, beans, and squash), managing forests, and cultivating an immense diversity of plant and animal species. Their societies were built upon sustainable practices, deeply integrated with the natural world. This era saw the co-evolution of human cultures and the genetic resources around them, creating unique landraces and traditional varieties perfectly adapted to local conditions and human needs.

Colonialism and Dispossession: The arrival of Europeans ushered in an era of catastrophic change. Land was seized, often violently, leading to forced removals, the destruction of traditional agricultural systems, and the loss of access to ancestral plant and animal populations. Diseases introduced by Europeans decimated populations, severing intergenerational chains of knowledge transmission about specific genetic resources.

The Rise of "Extractive Science": In the 19th and 20th centuries, scientific endeavors often mirrored colonial patterns. Researchers, driven by curiosity or the desire for commercial gain, frequently collected biological samples (human remains, plant specimens, animal parts) from Native American lands and peoples without consent or proper attribution. Human remains were exhumed from burial sites and stored in museums; medicinal plants were documented and sometimes patented by pharmaceutical companies without tribal benefit. This "extractive science" viewed Indigenous bodies and knowledge as raw materials to be taken, rather than as sovereign entities or intellectual property to be respected.

The "Blood Quantum" Conundrum: Even the very definition of Native American identity became entangled with genetics through the problematic concept of "blood quantum." Imposed by the U.S. government, this system attempted to quantify Native ancestry, often with the intent to diminish tribal populations and claim more land. While not directly about genetic resources, it illustrates how Western frameworks have historically sought to define and control Indigenous identity through biological parameters, further underscoring the need for Indigenous self-determination over their own biological and genetic information.

This history has instilled a deep distrust of external researchers and institutions, making the current efforts for protection a vital means of reclaiming agency and rectifying past injustices.

Why Protection Matters: Identity, Sovereignty, and the Future

For Native American tribes, the protection of genetic resources is not a niche scientific concern; it’s fundamental to their very existence and future.

- Identity and Ancestry: Genetic information, particularly human DNA, is intimately linked to individual and communal identity. It traces ancestral lines, validates oral histories, and strengthens connections to specific places and peoples. The unauthorized study or commercialization of this data is an affront to selfhood and heritage. Similarly, heirloom seeds and traditional animal breeds are living testaments to generations of stewardship and ingenuity, embodying the identity of the people who cultivated them.

- Tribal Sovereignty: The ability to control, manage, and benefit from one’s own resources – including genetic resources – is a cornerstone of sovereignty. This means tribes must have the power to decide who accesses their lands, who studies their peoples, how their traditional knowledge is used, and how any benefits derived are shared. Without this control, sovereignty is incomplete.

- Cultural Preservation: Many genetic resources are directly tied to specific cultural practices, ceremonies, languages, and belief systems. For instance, sacred plants are central to spiritual rituals, and their genetic integrity and continued existence are vital for the perpetuation of those traditions. Losing access to or control over these resources risks the erosion of cultural identity.

- Economic Justice and Benefit Sharing: The potential for commercial exploitation of genetic resources (e.g., pharmaceuticals derived from traditional medicinal plants, agricultural innovations from heirloom crops) is immense. Protection ensures that if such resources are used, tribes receive equitable benefits and that their traditional knowledge is recognized and compensated. This prevents biopiracy and promotes economic self-sufficiency.

- Food Security and Environmental Resilience: Traditional crops and animal breeds often possess unique genetic traits that make them resilient to local pests, diseases, and changing climates. Protecting these genetic resources is critical for tribal food security and for contributing to global biodiversity and climate adaptation strategies. Their traditional ecological knowledge offers sustainable pathways that Western science is only now beginning to appreciate.

- Future Generations: The responsibility to protect these resources extends to future generations. Ensuring the continuity of human genetic heritage, the diversity of traditional crops, and the knowledge systems that sustain them is a sacred trust.

Mechanisms and Strategies for Protection

The "map" of protection is being actively drawn through a combination of legal frameworks, ethical principles, and community-led initiatives.

Legal Frameworks:

- Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA, 1990): A landmark U.S. law requiring federal agencies and museums to inventory their collections of Native American human remains, funerary objects, sacred objects, and objects of cultural patrimony, and to consult with tribal nations for their repatriation. This was a crucial step in reclaiming ancestral human genetic material and challenging the historical exploitation of Indigenous bodies.

- International Conventions: The Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), while not directly addressing human genetics, emphasizes national sovereignty over genetic resources and calls for fair and equitable benefit-sharing. The Nagoya Protocol further operationalizes this, requiring Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC) from Indigenous and local communities for access to their genetic resources and associated traditional knowledge. The UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) affirms Indigenous peoples’ rights to self-determination, their traditional knowledge, and their cultural heritage, providing a robust international framework for protection.

- Tribal Laws and Policies: Increasingly, tribal nations are developing their own laws, research protocols, and Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) to govern access to and use of their genetic resources and associated data. These tribal-specific regulations often go beyond federal or international laws, reflecting unique cultural values and a strong commitment to data sovereignty.

Ethical Principles:

- Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC): This is paramount. No research, collection, or commercialization of genetic resources should occur without the full and transparent consent of the relevant tribal nation, obtained before any action is taken.

- Data Sovereignty: Tribes are asserting their right to own, control, access, and possess their own data, including genetic data, regardless of where it is stored. This means they decide who has access, for what purpose, and for how long.

- Benefit-Sharing: Any commercial or scientific benefits derived from Indigenous genetic resources or knowledge must be shared equitably with the originating communities.

- Respect for Traditional Ecological Knowledge: Acknowledging TEK as a legitimate and valuable form of science, and ensuring its protection from misappropriation.

Community-Led Initiatives:

- Tribal Biobanks and Seed Banks: Tribes are establishing their own facilities to preserve traditional seeds, plant varieties, and even human genetic samples, ensuring they remain under tribal control. Examples include the Akwesasne Seed Bank.

- Repatriation Efforts: Beyond NAGPRA, tribes are actively working to repatriate not just physical remains but also data, photographs, and other cultural items from institutions worldwide.

- Indigenous Research Methodologies: Developing research approaches that are culturally appropriate, community-driven, and benefit the tribe directly, shifting away from Western, extractive models.

- Cultural Heritage Centers: These centers play a vital role in documenting, preserving, and transmitting traditional knowledge about genetic resources to younger generations.

The Role of the "Map" in Education and Responsible Travel

For those engaging with Native American cultures through travel or education, understanding this "unseen map" is not just intellectually enriching; it’s a moral imperative.

- Educate Yourself: Before visiting Native lands or engaging with Indigenous communities, learn about their history, culture, and current issues, including their efforts to protect genetic resources and sovereignty. Support organizations that work with tribes on these issues.

- Respect Sovereignty: Recognize that tribal nations are sovereign governments. This means respecting their laws, customs, and protocols, especially regarding sacred sites, natural resources, and any cultural materials.

- Support Ethical Tourism: Choose tourism operators and businesses that are tribally owned or that have established ethical partnerships with Indigenous communities. Ensure that your tourism dollars directly benefit the local people and their cultural preservation efforts.

- Be Mindful of Traditional Knowledge: If you encounter traditional ecological knowledge (e.g., information about medicinal plants), treat it with the utmost respect. Do not appropriate it, share it widely without permission, or attempt to commercialize it. Recognize that this knowledge is intellectual property.

- Advocate for Rights: Support policies and legislation that uphold Indigenous rights, including those related to land, cultural heritage, and genetic resources.

Conclusion

The "Map of Native American genetic resources protection" is a dynamic, living entity – drawn by history, informed by identity, and constantly reshaped by the resilience and determination of Indigenous peoples. It highlights the profound interconnectedness between land, life, and culture, offering invaluable lessons for all humanity about sustainable stewardship, respect for diversity, and the imperative of justice.

For travelers and educators, this map serves as a guide, not to physical locations alone, but to a deeper understanding of Indigenous sovereignty and the critical importance of protecting these irreplaceable resources. By engaging with this complex map, we move beyond superficial appreciation towards a genuine respect for Native American cultures, their past struggles, and their ongoing contributions to the health of our planet and the richness of human experience. The journey to truly understand this map is one of continuous learning, humility, and active support for Indigenous self-determination.