A map of Native American frontier conflicts is far more than a geographical representation of skirmishes and battlefields; it is a profound historical document, a tapestry woven with threads of competing visions, broken promises, fierce resistance, and enduring identity. For the history enthusiast or the conscious traveler, understanding this map offers an unparalleled insight into the formation of North America, the resilience of its Indigenous peoples, and the complex, often tragic, legacy that continues to shape contemporary identities. This map is not static; it chronicles a dynamic, evolving frontier, marking the relentless push of European and later American expansion against the steadfast sovereignty and diverse cultures of hundreds of Native nations.

The Anatomy of a Conflict Map: More Than Just Red Dots

Imagine a detailed map spanning from the colonial East Coast in the 17th century all the way to the far reaches of the American West in the late 19th century. What would it reveal?

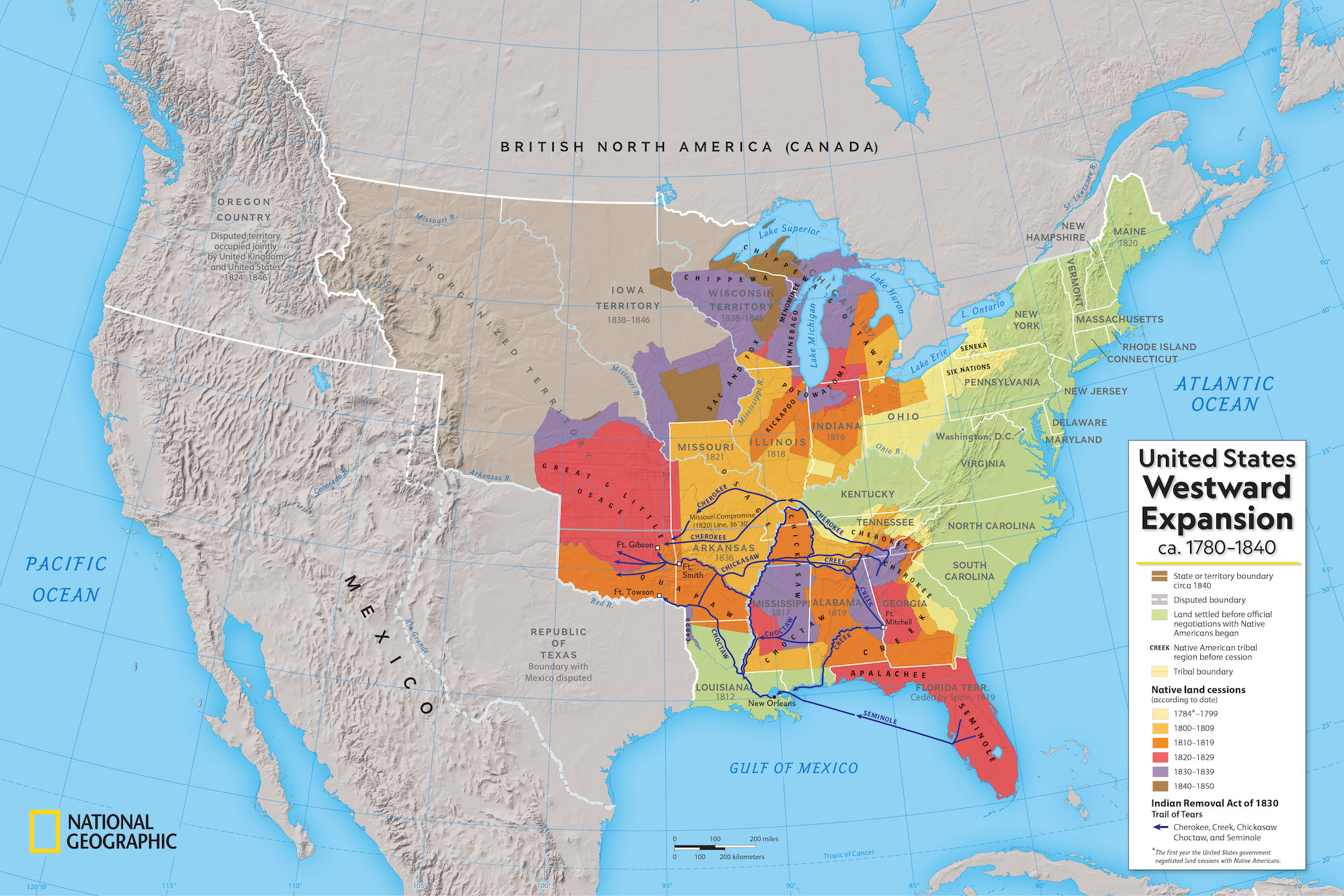

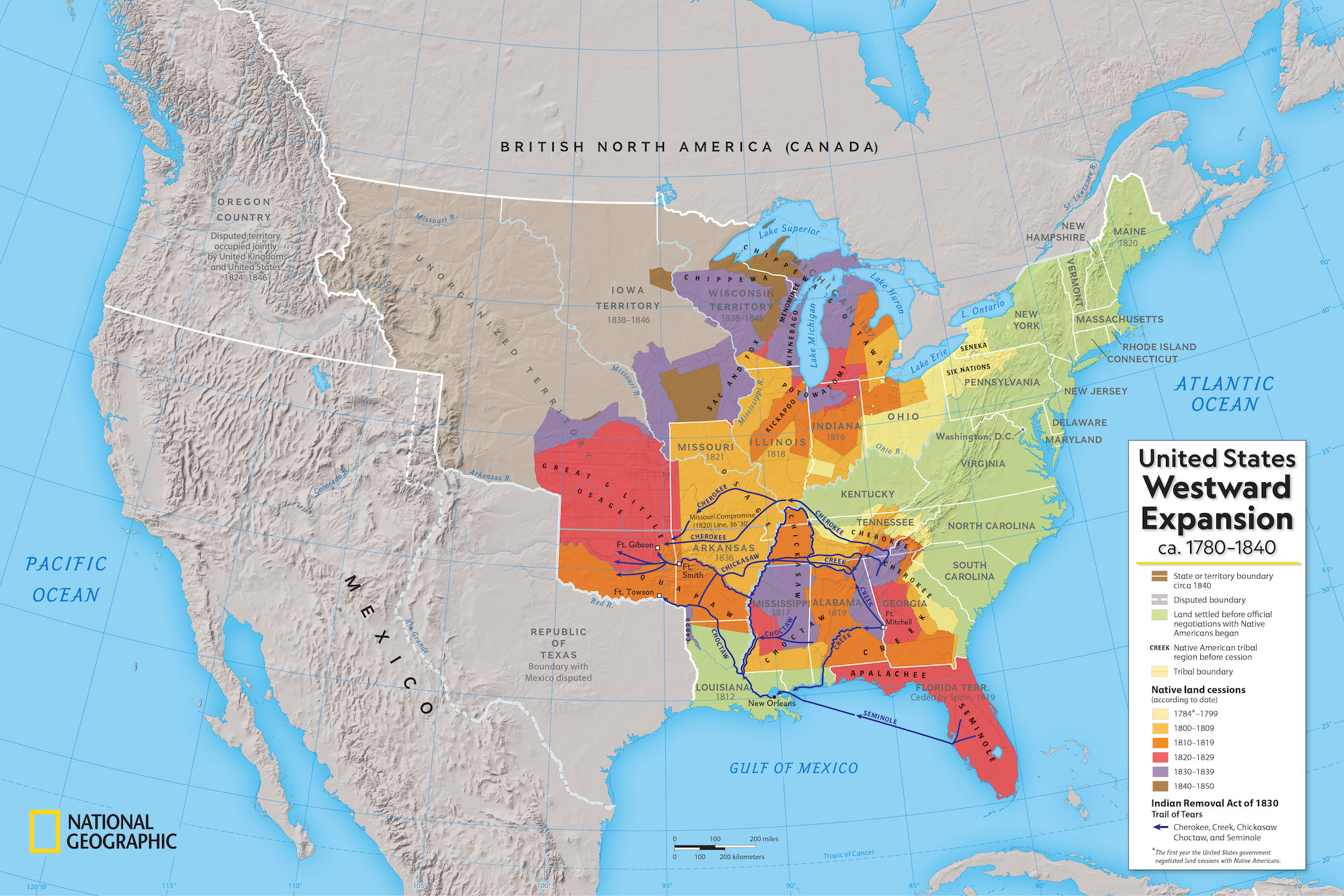

- Tribal Territories (Pre and Post-Contact): Layers indicating the vast, often overlapping, traditional lands of various Native American nations before and after significant conflicts. This visually emphasizes the immense territorial losses.

- Battle Sites and Skirmishes: Pinpoints marking specific engagements – from major battles like Little Bighorn to countless smaller, localized resistances. Each dot represents lives lost, strategies employed, and pivotal moments.

- Forts and Military Outposts: Locations of colonial and later U.S. military forts, which served as staging grounds for campaigns, centers of trade (often unequal), and symbols of encroaching power.

- Treaty Lines and Cessions: Lines illustrating the numerous treaties signed, often under duress, and the subsequent land cessions. These lines frequently shifted, were often violated by settlers or the government, and highlight the legalistic facade of dispossession.

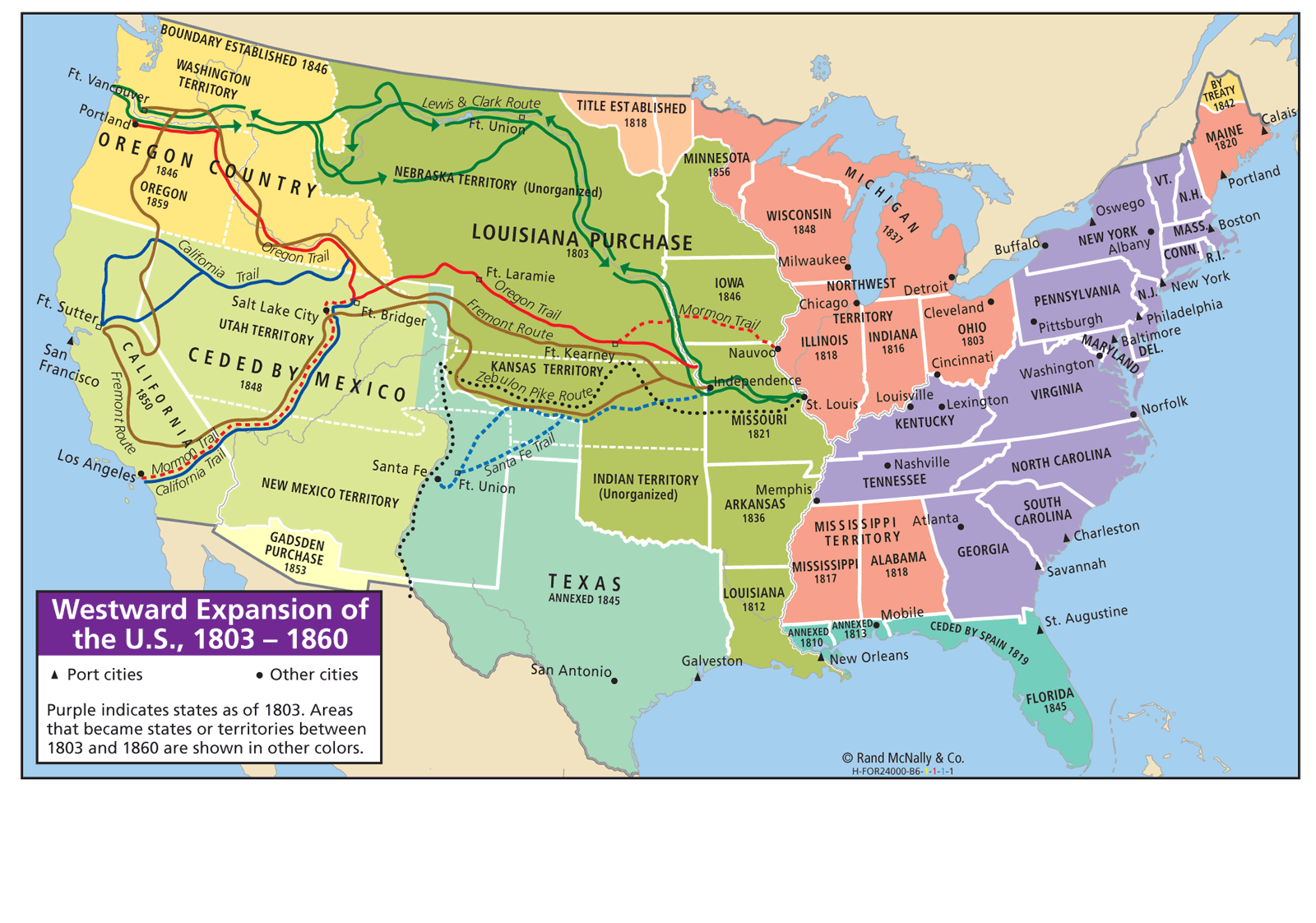

- Migration and Removal Routes: Tracing the forced displacement of entire nations, most famously the "Trail of Tears," but also countless smaller, lesser-known removals. These routes underscore the human cost of expansion.

- Resource Hotspots: Areas rich in resources like fur, timber, gold, or fertile land, which often fueled the desire for expansion and ignited conflicts.

- Paths of Expansion: Showing the general westward movement of settlers, marked by routes like the Oregon Trail, reflecting the ideology of Manifest Destiny.

Such a map is a powerful educational tool, allowing us to visualize the staggering scale of the conflicts and the systematic nature of territorial acquisition. But beyond the geography, it tells a story of identity – how it was challenged, defended, and ultimately, redefined.

Early Encounters: The Eastern Frontier (17th – 18th Centuries)

The earliest frontier conflicts erupted along the Atlantic seaboard as European colonies established footholds. Here, the map would highlight interactions between:

- Wampanoag, Narragansett, Pequot (New England): These nations, led by figures like Metacom (King Philip), fiercely resisted English encroachment, leading to devastating wars such as King Philip’s War (1675-1678). This conflict, marked by extreme violence on both sides, profoundly shaped the identity of both the nascent American colonies and the surviving Native communities, leading to increased European dominance and the decimation of Indigenous populations. For the Wampanoag, identity became intertwined with survival and the memory of profound loss.

- Powhatan Confederacy (Virginia): Initially engaging in trade and diplomacy with the Jamestown settlers, conflicts soon arose over land and resources. Figures like Pocahontas and Chief Powhatan symbolize the early, complex attempts at coexistence and the inevitable clash when cultural boundaries were crossed. The legacy for the Powhatan was one of continuous struggle to maintain their cultural distinctiveness against overwhelming pressure.

- Iroquois Confederacy (Haudenosaunee) and Algonquin Nations (New York/Great Lakes): These powerful groups became key players in the Anglo-French rivalry, skillfully playing European powers against each other to maintain their sovereignty. Pontiac’s Rebellion (1763), following the French and Indian War, saw a unified effort by various Great Lakes tribes, including the Ottawa, Ojibwe, and Potawatomi, to resist British expansion. This demonstrated a nascent pan-Indian identity in the face of a common threat, even as it ultimately failed to halt the tide. Their identity was forged in strategic alliance and military prowess.

For the Native peoples of the East, identity was often tied to specific homelands, spiritual traditions, and intricate social structures. The conflicts forced a painful re-evaluation, sometimes leading to alliances, sometimes to desperate last stands, and always to an enduring spirit of cultural preservation despite immense pressure.

The Trans-Appalachian Frontier and the Old Northwest (Late 18th – Early 19th Centuries)

As the United States gained independence, its frontier pushed westward over the Appalachian Mountains. The map here would be dense with conflicts in the Ohio River Valley and Great Lakes region, involving:

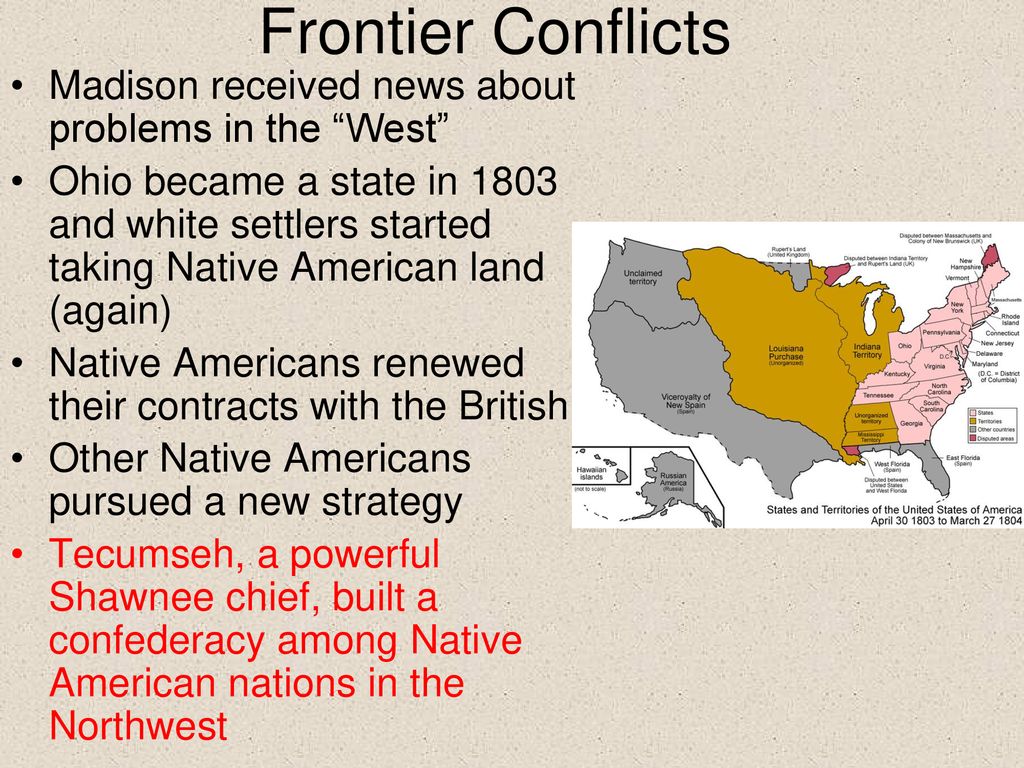

- Shawnee, Miami, Delaware, Wyandot: These nations formed powerful confederacies to resist American settlement of the "Ohio Country." Figures like Tecumseh (Shawnee) emerged as visionary leaders, advocating for a united Native American front against the U.S. The Battle of Fallen Timbers (1794) and Tecumseh’s War (culminating in the Battle of Tippecanoe in 1811) were pivotal.

- Identity: Tecumseh’s movement was a powerful assertion of a pan-Indian identity, transcending individual tribal loyalties to defend a shared way of life and sovereignty. His legacy continues to inspire Native peoples as a symbol of unity and resistance. The map would show the gradual erosion of this collective power, leading to further land cessions and forced migrations.

The Southeastern Removals (Early-Mid 19th Century)

The map of the Southeast would highlight a different kind of conflict – one often fought in courts and through political maneuvering, culminating in forced removal.

- Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, Seminole ("Five Civilized Tribes"): These nations, having adopted many aspects of American culture (written languages, constitutional governments, farming methods), still faced the insatiable demand for their lands, especially after the discovery of gold in Cherokee territory. The Indian Removal Act of 1830 led to:

- The Trail of Tears (1838-1839): The forced march of the Cherokee and other nations from their ancestral lands to Indian Territory (Oklahoma). This is a stark, tragic line on the map, representing immense suffering and loss of life.

- Seminole Wars (Florida): A protracted and costly series of conflicts (1816-1858) where the Seminole, often allied with runaway slaves, fiercely resisted removal from the Florida Everglades.

- Identity: For these nations, identity was challenged by the very act of "civilization" – attempts to assimilate were met with betrayal. The Cherokee’s legal battles, led by figures like John Ross, defined an identity rooted in legal rights and nationhood. The Seminole’s long, bloody resistance forged an identity of defiant independence and unwavering connection to their unique homeland, making them the only tribe never formally to sign a peace treaty with the U.S. government.

The Great Plains and the Western Indian Wars (Mid-Late 19th Century)

The latter half of the 19th century saw the frontier shift to the vast plains and mountains of the West, leading to the most iconic and often romanticized "Indian Wars." The map here would be a web of military campaigns, buffalo hunting grounds, and the shrinking territories of:

-

Lakota (Sioux), Cheyenne, Arapaho: These nations, whose lives revolved around the buffalo and nomadic hunting, clashed violently with settlers, miners, and the U.S. Army. Key conflicts include:

- Sand Creek Massacre (1864): A horrific attack on a peaceful Cheyenne and Arapaho village, symbolizing the brutality often inflicted upon Native communities.

- Battle of Little Bighorn (1876): A decisive victory for the Lakota and Cheyenne, led by Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse, against Custer’s 7th Cavalry. This is a crucial dot on the map, representing a temporary triumph against overwhelming odds.

- Wounded Knee Massacre (1890): The tragic end of the major frontier conflicts, where hundreds of unarmed Lakota were killed, marking the brutal suppression of the Ghost Dance movement and the end of armed resistance.

- Identity: For the Plains tribes, warrior culture, spiritual beliefs centered on the land and the buffalo, and a strong sense of community defined their identity. The conflicts were a desperate struggle to preserve this way of life against its systematic destruction. Figures like Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse became embodiments of courage, spiritual power, and an unyielding commitment to their people’s freedom.

-

Apache (Southwest): Known for their fierce independence and masterful guerrilla warfare in the rugged terrain of Arizona and New Mexico.

- Geronimo (Chiricahua Apache): His decades-long resistance against both Mexican and U.S. forces made him a legendary figure. His band’s relentless evasion demonstrated an identity defined by freedom and an unbreakable will to resist confinement. The map would show the challenging terrain that allowed such prolonged resistance.

-

Comanche (Southern Plains): Often called "Lords of the Plains," they dominated vast territories through their equestrian skills and military prowess. Their resistance to Texas and U.S. expansion was fierce, ending with the Red River War (1874-1875).

- Identity: Their identity was intrinsically linked to their mastery of horsemanship, their hunting culture, and their formidable reputation as warriors.

-

Nez Perce (Pacific Northwest): Known for their peaceful relations and selective breeding of horses (Appaloosas).

- Chief Joseph: His eloquent plea for peace and his strategic retreat during the 1877 Nez Perce War, a desperate attempt to reach Canada, represent an identity of dignity, resilience, and a deep love for their homeland, even in the face of overwhelming military might. The map would trace their incredible 1,170-mile flight.

Beyond the Battles: The Enduring Legacy and Identity

The "Map of Native American Frontier Conflicts" does not end with the last battle. Its most profound lesson lies in its aftermath. The lines of reservations, the forced assimilation policies (boarding schools, suppression of language and religion), and the ongoing struggle for self-determination are the continuation of this historical narrative.

For Native Americans today, the map serves as:

- A Memory and a Warning: It is a powerful reminder of the injustices faced, the lands lost, and the lives sacrificed. This shared history forms a bedrock of contemporary Native identity, fostering a strong sense of community and a collective determination to prevent such atrocities from happening again.

- A Source of Resilience and Pride: Despite the immense pressures, Native cultures survived. The map’s dots and lines represent not just defeats, but also acts of incredible bravery, strategic brilliance, and unwavering commitment to cultural survival. This resilience is a core component of modern Native identity, fueling efforts in language revitalization, cultural resurgence, and political advocacy.

- A Foundation for Sovereignty: The treaties, though often broken, still represent legal agreements between sovereign nations. Modern movements for tribal sovereignty and self-governance are rooted in these historical documents and the inherent rights fought for on these conflict-laden lands.

- A Call for Understanding: For travelers and history enthusiasts, this map is an invitation to look beyond simplistic narratives of "settlers vs. savages" and to appreciate the complexity, diversity, and enduring spirit of Indigenous peoples. It encourages a visit to tribal museums, cultural centers, and historical sites, offering a deeper, more respectful engagement with the land and its original inhabitants.

In conclusion, the "Map of Native American Frontier Conflicts" is an indispensable educational tool. It is a stark visual chronicle of the profound transformations that shaped North America, detailing not just where battles were fought, but why, and at what cost. More importantly, it is a testament to the enduring identities of hundreds of Native nations – identities forged in fire, defined by resistance, marked by loss, but ultimately characterized by an unyielding spirit of survival, cultural revitalization, and the ongoing pursuit of justice and self-determination in the present day. To trace these lines and dots is to walk through a history that profoundly impacts who we are as a continent, and to acknowledge the vibrant, continuing legacy of its first peoples.