Navigating Ancestral Waters: A Map of Native American Fishing Territories, A Tapestry of History and Identity

To look upon a map of Native American fishing territories is to gaze not merely at lines on parchment, but into the very soul of a continent. It is an invitation to understand an enduring human relationship with water, a story etched across millennia, pulsating with history, identity, and profound resilience. Far from being simple resource charts, these maps delineate complex webs of culture, economy, spirituality, and sovereignty, offering an invaluable lens for both the curious traveler and the dedicated student of history. They reveal that for Indigenous peoples across North America, fishing was, and remains, far more than sustenance; it is a way of life, a sacred trust, and a fundamental pillar of identity.

The Pristine Past: Pre-Colonial Harmony and Sustainable Stewardship

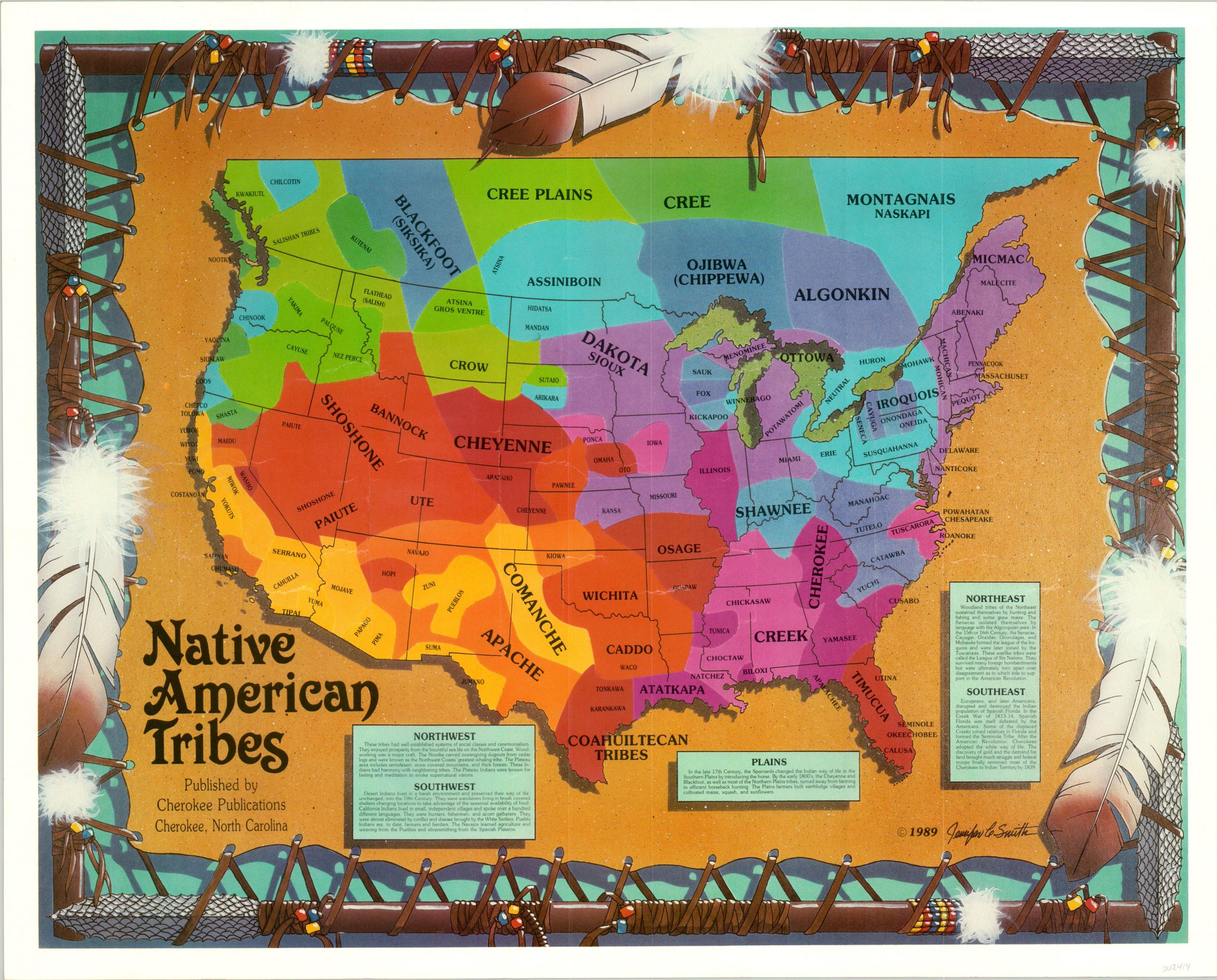

Before the arrival of European powers, the waterways of North America teemed with life, and Indigenous communities thrived in intimate communion with them. From the salmon-rich rivers of the Pacific Northwest to the vast Great Lakes, the Atlantic estuaries, and the intricate river systems of the interior, diverse Native nations developed sophisticated and sustainable fishing practices perfectly adapted to their unique environments.

Diversity of Practices and Species: The variety of fishing traditions was as diverse as the tribes themselves. Along the Columbia River, tribes like the Yakama, Umatilla, and Warm Springs developed intricate systems of weirs and dip nets to harvest millions of migrating salmon and lamprey. On the Pacific Coast, nations like the Haida, Tlingit, and Coast Salish mastered deep-sea fishing for halibut and cod, utilizing massive cedar canoes and sophisticated hooks, while also building elaborate intertidal traps for salmon and shellfish. In the Great Lakes region, the Anishinaabeg (Ojibwe, Odawa, Potawatomi) skillfully speared and netted whitefish, lake trout, and walleye, navigating treacherous waters in birch bark canoes. Along the Atlantic seaboard, the Wampanoag and Penobscot peoples harvested cod, mackerel, and an abundance of shellfish, including clams, oysters, and mussels, often managing estuarine fish runs with brush weirs.

Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK): Underlying these practices was a profound Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK)—a holistic understanding of ecosystems accumulated over countless generations. Indigenous peoples understood the delicate balance of their environments. They practiced selective harvesting, allowing populations to regenerate. They knew the seasonal rhythms of fish migrations, the spawning grounds, and the indicators of ecological health. This knowledge was not merely practical; it was interwoven with spiritual beliefs that viewed fish, water, and all living things as relatives, deserving of respect and gratitude. Ceremonies like the First Salmon Ceremony in the Pacific Northwest reinforced this spiritual connection, ensuring the continuity of life and the renewal of resources. Fishing territories were not just places to take; they were places to care for, to steward, and to honor.

Economic and Social Hubs: Fishing territories were also vital economic and social centers. Dried and smoked fish, particularly salmon, served as a primary food source, providing essential protein and nutrients year-round. Surplus fish became a valuable trade commodity, fostering extensive inter-tribal networks that exchanged goods, knowledge, and culture across vast distances. Potlatches in the Pacific Northwest, for example, were elaborate ceremonies where wealth, often accumulated through fishing and hunting, was redistributed, cementing social status and community bonds. The control and management of these territories, therefore, were central to a tribe’s prosperity, sovereignty, and cultural integrity.

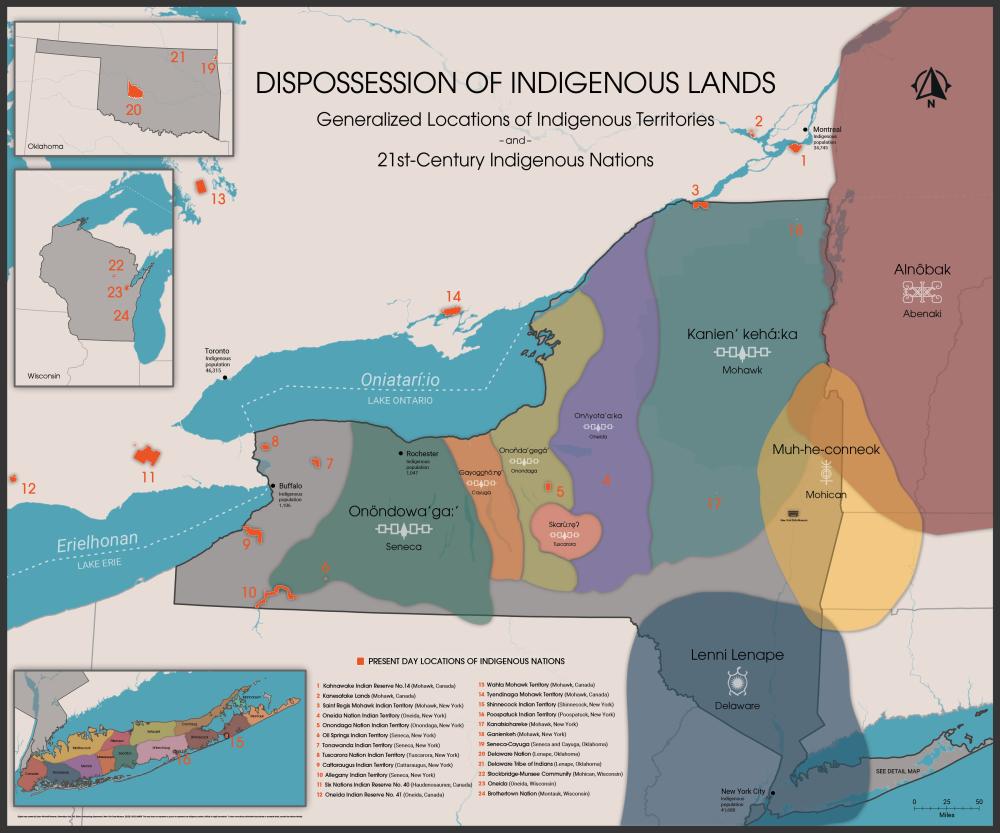

The Cataclysm of Contact: Dispossession and Disruption

The arrival of European colonists marked a devastating turning point. The concept of "empty land" or terra nullius—a legal fiction used to justify seizure—ignored the millennia of Indigenous stewardship and the complex territorial maps of Native nations. As colonial expansion accelerated, Native fishing territories were systematically disrupted, diminished, and often destroyed.

Land Seizure and Resource Depletion: Treaties, often coerced and rarely honored by the colonizers, typically ceded vast tracts of land, pushing tribes onto reservations, frequently far from their traditional fishing grounds. The subsequent industrialization of waterways—damming rivers for hydroelectricity and irrigation, logging that caused massive siltation, and pollution from burgeoning industries—decimated fish populations. Commercial overfishing by non-Native settlers, driven by market demand rather than sustainable practices, further depleted stocks that had sustained Indigenous communities for millennia. The impact was catastrophic, severing the physical and spiritual connection between people and their ancestral waters.

The Erasure of Identity: Beyond the economic and dietary impacts, the loss of fishing territories was an assault on Indigenous identity itself. For many tribes, fishing was inextricably linked to their language, ceremonies, governance, and social structures. The inability to practice traditional fishing meant the erosion of cultural practices, the disruption of intergenerational knowledge transfer, and a profound sense of loss that reverberated through communities. It was an intentional act of cultural genocide, aimed at assimilating Indigenous peoples into the dominant society by stripping away their self-sufficiency and distinct ways of life.

The Long Fight: Treaty Rights, Resilience, and Reclamation

Despite the immense pressures, Native American tribes never fully relinquished their claims to their ancestral fishing territories. The fight to retain, reclaim, and protect these rights has been a long, arduous, and often heroic struggle, unfolding in courtrooms, on the water, and in political arenas.

The Power of Treaty Rights: Central to this struggle has been the assertion of "reserved rights" in historical treaties. Many treaties, while ceding land, explicitly or implicitly reserved the right for tribes to hunt, fish, and gather on their "usual and accustomed places" off-reservation. These rights were often ignored or actively suppressed by state and federal governments for over a century. However, landmark legal decisions in the mid-20th century began to uphold these inherent rights.

Perhaps the most significant example is the Boldt Decision (United States v. Washington, 1974), which affirmed that tribes in Western Washington were entitled to 50% of the harvestable salmon in their traditional fishing areas. This decision, and subsequent rulings, recognized not only a right to fish but also the right to co-manage the resource, fundamentally shifting the power dynamics and acknowledging tribal sovereignty. Similar legal battles and agreements have secured fishing rights for tribes in the Great Lakes (e.g., United States v. Michigan, 1979) and other regions, often after decades of "fish wars" characterized by tension, arrests, and even violence.

Cultural Resurgence and Economic Sovereignty: Today, the map of Native American fishing territories is not just a historical document; it is a living testament to cultural resurgence and economic sovereignty. Tribes are actively rebuilding their fisheries, often employing a blend of traditional ecological knowledge and modern science. They are managing hatcheries, restoring spawning habitats, and advocating for dam removal to allow fish migrations to resume.

For many tribes, tribal fisheries are a cornerstone of economic development, creating jobs, generating revenue, and providing healthy, culturally significant food. This includes commercial fishing operations, aquaculture, and cultural tourism initiatives that share traditional fishing practices with respectful visitors. This economic empowerment is crucial for self-determination, allowing tribes to invest in education, healthcare, and infrastructure within their communities.

Environmental Stewardship and Advocacy: Beyond their own economic and cultural well-being, Native nations are often at the forefront of environmental protection. Recognizing the interconnectedness of land, water, and life, tribes are powerful advocates for clean water, healthy ecosystems, and sustainable resource management for the benefit of all. They challenge industrial pollution, fight against unsustainable development projects, and champion policies that protect endangered species and restore degraded habitats. Their historical maps of fishing territories thus become blueprints for future environmental resilience, guiding efforts to heal and protect the land and water that have sustained them for millennia.

Engaging with the Living Map: A Traveler’s Perspective

For the modern traveler and student of history, understanding the map of Native American fishing territories offers a profound opportunity to engage with North America in a more meaningful way. When you visit a coastal community, a majestic river, or a pristine lake, consider the generations of Indigenous peoples who fished these very waters.

- Support Tribal Enterprises: Seek out and support tribal-owned businesses, including those involved in fishing, tourism, or cultural education. This directly contributes to tribal sovereignty and economic self-sufficiency.

- Visit Cultural Centers: Many tribes operate cultural centers or museums that offer invaluable insights into their fishing traditions, history, and ongoing efforts. These are places of learning and respectful engagement.

- Learn and Respect: Educate yourself about the specific tribes whose traditional territories you are visiting. Understand their history, their relationship to the land and water, and their contemporary issues. Be mindful of cultural protocols and respect sacred sites.

- Advocate for Water Protection: Recognize that the fight for healthy waterways is ongoing. Support organizations and initiatives that champion clean water, dam removal, and the protection of aquatic ecosystems, many of which are led or strongly supported by Indigenous communities.

Conclusion: A Legacy Carved in Water

The map of Native American fishing territories is far more than a geographical representation; it is a powerful narrative of survival, adaptation, and unwavering identity. It reminds us that every river, every lake, every coastline holds layers of Indigenous history, spirituality, and a deep, enduring connection to the natural world. It challenges us to look beyond simplistic narratives of discovery and settlement, and instead, to see a continent shaped by millennia of Indigenous stewardship.

In a world grappling with environmental crises and the urgent need for sustainable practices, the wisdom embedded in these ancestral fishing territories offers invaluable lessons. By understanding and respecting these maps—not as relics of the past, but as vibrant, living documents—we honor the resilience of Native American nations and gain a deeper appreciation for the intricate, sacred relationship between humanity and the waters that sustain us all. It is a legacy carved in water, flowing through time, and continuing to shape the present and future of this continent.