The Ghostly Hues of History: Navigating the Map of Native American Disease Impact

The Map of Native American Disease Impact is not a casual cartographic curiosity; it is a profound and somber historical document, a visual lament etched with the contours of demographic catastrophe and cultural upheaval. For any traveler seeking to truly understand the landscapes, the peoples, and the layered histories of North America, this map is an indispensable, albeit heartbreaking, guide. It transcends mere geography, offering a window into the biological, social, and spiritual unraveling that reshaped an entire continent long before the arrival of large-scale European settlement. Forget the romanticized notions of "empty wilderness"; this map reveals a land violently emptied by forces unseen, forces that irrevocably altered the course of human destiny in the Americas.

The Unseen Weapon: "Virgin Soil" Epidemics

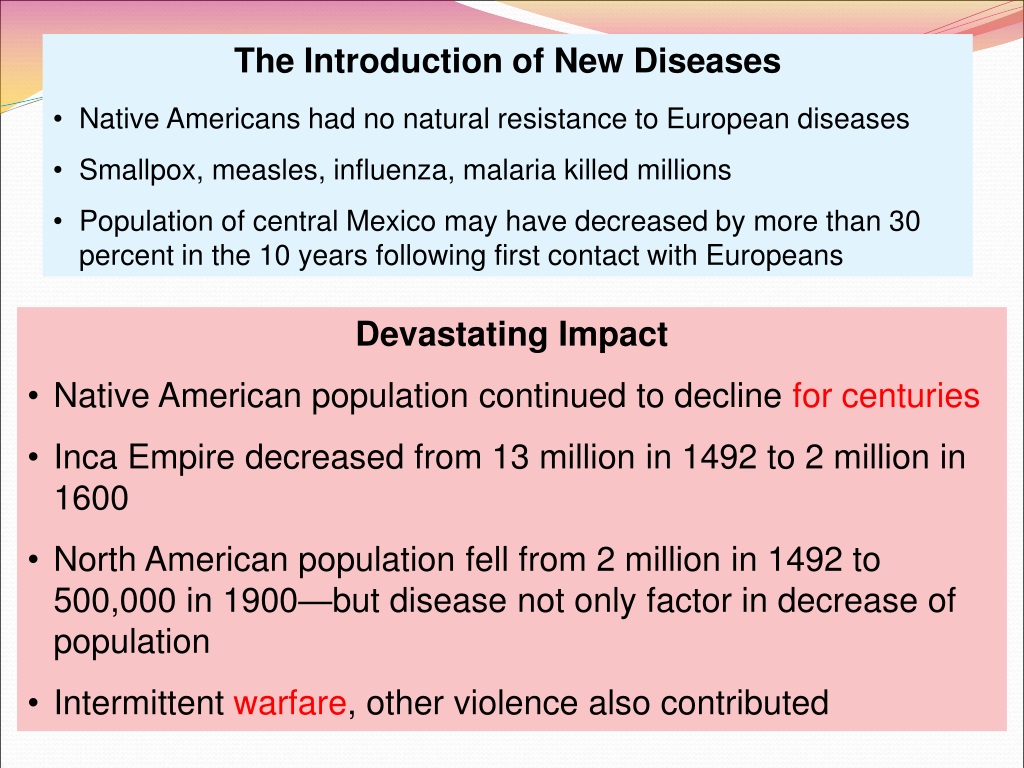

To grasp the map’s chilling significance, one must first comprehend the concept of "virgin soil epidemics." For millennia, the populations of the Old World (Europe, Asia, Africa) lived in close proximity to domesticated animals and in dense urban centers, fostering a constant exchange of pathogens. Over generations, these populations developed a degree of acquired immunity or genetic resistance to a host of diseases – smallpox, measles, influenza, typhus, bubonic plague, diphtheria, mumps, whooping cough, chickenpox, cholera, malaria, yellow fever, and more. While devastating, these diseases were often endemic, meaning a significant portion of the population had survived previous outbreaks, passing on some level of resistance.

The Americas, however, were a different biological world. Isolated for thousands of years after the last major migrations across the Bering land bridge, Indigenous populations had evolved without exposure to these specific pathogens. They lacked the acquired immunities and genetic resistances common in the Old World. When Europeans arrived, they brought not only their cultures and technologies but also a silent, invisible armada of microorganisms. For Native Americans, every new disease introduced was a "virgin soil" epidemic, meaning it swept through a population with no prior exposure whatsoever. The result was an unprecedented level of mortality, far exceeding anything seen in the Old World, where even the Black Death, horrific as it was, still left a significant proportion of the population alive due to prior exposure and partial immunity.

The Cascade of Plagues: Primary Culprits and Their Devastation

The map primarily traces the devastating spread of several key diseases, each leaving its own distinctive, tragic mark:

-

Smallpox (Variola Major): The undisputed king of killers. Highly contagious and often fatal, smallpox could wipe out 50-90% of an infected Native American population. Its symptoms – high fever, body aches, and characteristic pustules that left deep scars (pockmarks) on survivors – were terrifying. The disease often spread faster than the Europeans themselves, carried by trade networks, fleeing refugees, and even contaminated blankets, reaching deep into the interior before direct European contact.

-

Measles (Rubeola): While often considered a childhood illness today, measles was a deadly force in virgin soil populations. Highly contagious, it caused fever, rash, and often led to fatal complications like pneumonia or encephalitis, particularly in malnourished or already weakened communities.

-

Influenza (Flu): Often arriving in waves, influenza could rapidly incapacitate entire villages, making it impossible for people to hunt, gather, or care for the sick. The secondary infections that often followed were frequently fatal.

-

Typhus: Spread by lice and fleas, typhus thrived in conditions of crowding, poor sanitation, and stress – all exacerbated by the disruptions of European contact and the forced displacement of populations.

-

Other Diseases: Diphtheria, whooping cough, chickenpox, and even sexually transmitted diseases like gonorrhea and syphilis (though the origin of syphilis in the Old World is debated, its introduction to Native American populations certainly added to their burden) also contributed to the overall decline.

The map, therefore, is not just about isolated outbreaks but about a series of overlapping and successive epidemics that repeatedly hammered communities, preventing recovery and perpetuating a cycle of decline.

Visualizing Catastrophe: What the Map Reveals

A typical "Map of Native American Disease Impact" utilizes a combination of visual cues to convey its powerful message:

- Color-coding and Shading: Different shades of a color (often red or brown, signifying loss) or distinct colors are used to represent varying degrees of population decline. Darker shades might indicate 90-95% mortality, while lighter shades show 50-70% decline. This immediately draws the eye to areas of most severe impact.

- Timelines and Dates: Overlaid dates or chronological markers indicate when specific epidemics swept through particular regions. This highlights that the "Great Dying" was not a single event but a prolonged, multi-century process, with different areas experiencing peak mortality at different times.

- Arrows and Routes of Spread: Lines and arrows often depict the likely pathways of disease transmission. These typically follow major rivers, established Indigenous trade routes, and the paths of early European explorers, missionaries, and traders. This illustrates how diseases leapfrogged across vast distances, often ahead of the actual colonizers.

- Population Estimates: Accompanying text or legends often provide pre-Columbian population estimates and post-epidemic figures, starkly illustrating the magnitude of the loss. These numbers are, of course, estimates, but they consistently point to a continent-wide demographic collapse.

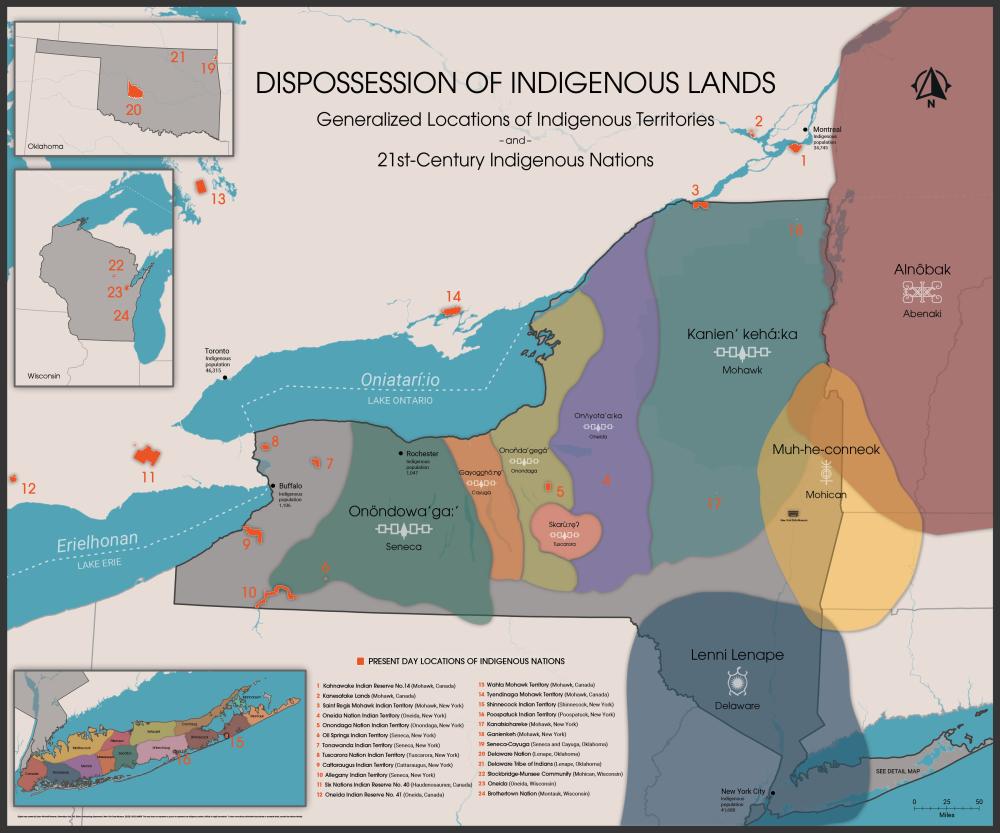

- Specific Tribal and Regional Impacts: The map highlights particular tribal territories or cultural regions that were devastated. For instance:

- The Caribbean: The Taino people, the first to encounter Columbus, were virtually annihilated within decades, a grim harbinger.

- Mesoamerica: The Aztec and Inca empires, already weakened by internal strife, collapsed under the successive waves of smallpox, measles, and other diseases, paving the way for Spanish conquest.

- The American Southwest: Pueblo communities, while sometimes initially resistant due to their fortified villages, eventually succumbed as diseases spread along trade routes with Spanish missions and settlements. The map shows pockets of severe loss even in seemingly remote areas.

- The Northeast: Tribes like the Wampanoag, Narragansett, and Iroquois Confederacy experienced devastating pre-contact epidemics (e.g., the "Great Dying" of 1616-1619 in New England), which significantly weakened them just prior to the arrival of English Pilgrims and Puritans, making colonization far easier.

- The Southeast: The sophisticated Mississippian cultures, responsible for vast mound cities like Cahokia, were already in decline before Europeans arrived in force, likely due to earlier waves of disease spreading from the Caribbean and Gulf Coast.

- The Pacific Northwest: Later in the colonial period, smallpox and other diseases ravaged coastal communities, sometimes intentionally spread through infected blankets, leaving behind depopulated villages and broken societies by the time American and Canadian settlers arrived in large numbers in the 19th century.

Beyond Demographics: Cultural, Social, and Spiritual Fallout

The map’s true power lies not just in the numbers but in what those numbers represent: the unraveling of entire civilizations. The impact extended far beyond mere population reduction:

- Loss of Knowledge and Oral Traditions: The elders, spiritual leaders, healers, and storytellers were often the first to die, taking with them generations of accumulated knowledge, history, spiritual practices, agricultural techniques, and medicinal wisdom. This created an irreversible break in the chain of cultural transmission.

- Social and Political Disruption: The rapid death toll shattered family structures, clan systems, and political hierarchies. Power vacuums emerged, leading to internal strife or making communities vulnerable to external enemies, both Indigenous and European. Inter-tribal warfare sometimes intensified as weakened groups struggled for resources or sought to fill power vacuums.

- Economic Collapse: Agricultural systems withered as there were too few hands to plant, tend, and harvest crops. Trade networks, which had been vital arteries of exchange for millennia, broke down. Famine often followed epidemics, further weakening survivors.

- Psychological and Spiritual Trauma: Survivors grappled with unimaginable grief and existential despair. Their gods and spirits seemed to have abandoned them. Traditional healing practices proved ineffective against the new diseases, leading to a crisis of faith and identity. The very fabric of their understanding of the world was torn apart.

- Facilitating Colonization: Perhaps the most insidious "impact" was how the disease decimated populations and cleared the land, making it appear "empty" to European settlers. The myth of the "pristine wilderness" or "virgin land" was, in many cases, a landscape made artificially empty by disease, not by a lack of prior human presence. This demographic collapse dramatically facilitated European conquest and settlement.

The Enduring Legacy and Contemporary Identity

The Map of Native American Disease Impact is a testament to immense tragedy, yet it is also a silent tribute to extraordinary resilience. Despite the unprecedented decimation, Native American peoples survived. They adapted, reformed, and found ways to preserve their cultures, languages, and identities.

Today, this history profoundly shapes contemporary Native American identity. It informs land claims, sovereignty movements, and efforts to revitalize languages and traditions. It underscores the deep connection to ancestral lands, even those emptied by disease. For modern Native Americans, this map is not just a historical relic; it is a part of their collective memory, a recognition of the immense sacrifices and struggles that their ancestors endured.

Why This Matters for Travelers and Educators

For anyone traveling through North America, particularly to areas rich in Indigenous history or natural beauty, understanding this map is crucial:

- Context for the Landscape: It provides essential context for archaeological sites, ancient ruins, and even seemingly "wild" landscapes. Those vast stretches of forest or plain were once home to thriving, complex societies.

- Deeper Appreciation for Native Cultures: It fosters a deeper appreciation for the resilience, adaptability, and enduring spirit of Native American peoples. Encountering contemporary Native communities, understanding their history of survival against such odds, transforms a superficial visit into a profound learning experience.

- Challenging Historical Narratives: It challenges simplistic narratives of "discovery" and "settlement," replacing them with a more nuanced, and often painful, understanding of the true cost of contact. It pushes us to acknowledge the profound human loss that underpins much of American history.

- Promoting Respect and Understanding: By acknowledging this history, we can engage with Native American sites and communities with greater respect, empathy, and a commitment to learning from the past. It encourages responsible tourism that honors the ancestral inhabitants of the land.

The Map of Native American Disease Impact is more than just data points on a page; it is a spectral reminder of the millions of lives lost, the cultures disrupted, and the course of a continent forever altered. It is a vital tool for anyone seeking to move beyond superficial narratives and engage with the rich, complex, and often sorrowful layers of North American history. It urges us to see the land not just as it is today, but as it once was, and to recognize the enduring spirit of those who survived the unseen storm.