Unveiling the Invisible: The Map of Native American Displacement, Resilience, and Enduring Identity

The concept of a "map of Native American diaspora" immediately conjures images of profound historical shifts and enduring cultural resilience. While not a traditional diaspora in the sense of a people scattered from a single homeland, the term effectively captures the widespread displacement, forced migration, and subsequent re-establishment of Indigenous communities across North America. These maps are not mere geographical representations; they are intricate tapestries woven with threads of ancestral memory, broken treaties, fierce resistance, and an unyielding connection to the land. For the curious traveler and the earnest student of history, understanding these maps is essential to grasping the true narrative of the continent, moving beyond simplistic narratives to appreciate the complex, living histories of its First Peoples.

Beyond the Blank Slate: Mapping Pre-Colonial North America

To truly understand the "diaspora," one must first acknowledge the vibrant, diverse, and deeply rooted world that existed before European contact. Pre-colonial North America was not an empty wilderness, but a continent teeming with hundreds of distinct Indigenous nations, each with its own language, governance, spiritual traditions, economic systems, and vast territories.

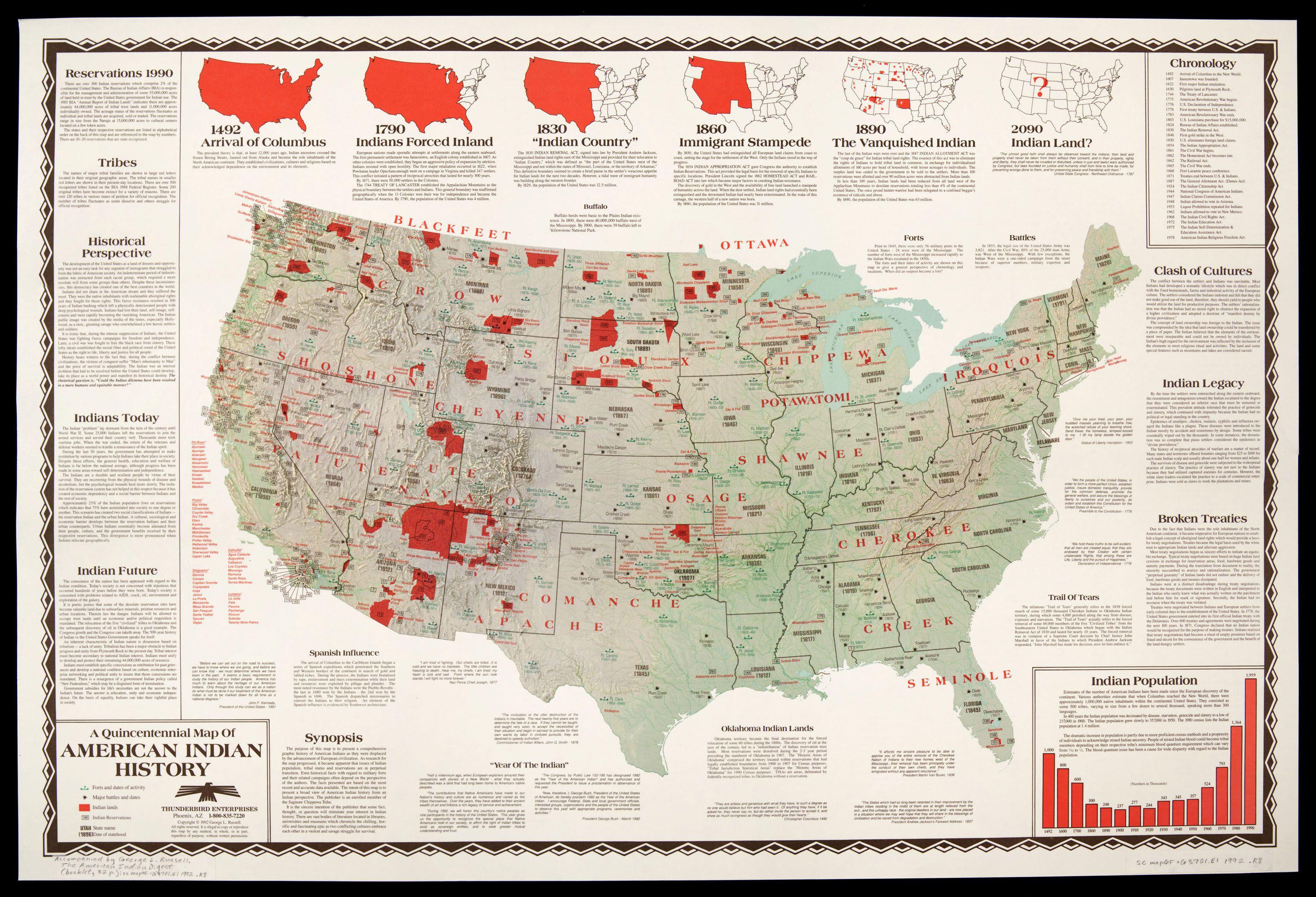

Modern attempts to map pre-colonial Indigenous lands, such as those by Aaron Carapella’s Tribal Nations Maps or the Native Land Digital project, are crucial tools. These maps challenge the myth of terra nullius (empty land) by illustrating the dynamic, often overlapping, and always occupied territories of nations like the Cherokee, Lakota, Iroquois Confederacy, Navajo, Apache, Anishinaabeg, and countless others. They show complex trade routes, diplomatic alliances, and even conflicts, demonstrating sophisticated societies that managed vast ecosystems. These are not static boundaries but fluid zones reflecting seasonal movements, hunting grounds, and agricultural practices. These initial maps, often reconstructed from oral histories, early explorer accounts, and archaeological evidence, serve as a vital baseline, reminding us of the immense loss and transformation that followed. They underscore that every subsequent movement was a deviation from a deeply established, sovereign presence.

The Cartography of Conquest: From Treaty Lines to Forced Removals

The arrival of European powers fundamentally altered the Indigenous landscape, initiating a period marked by land cessions, broken promises, and systematic displacement. The maps from this era tell a chilling story of shrinking territories and the relentless advance of colonial expansion.

I. The Treaty Era (17th – 19th Centuries): Early colonial maps often depicted Indigenous nations as independent entities, and European powers initially engaged in treaty-making to acquire land. These treaties, however, were almost universally misunderstood or deliberately violated. Indigenous nations often viewed treaties as agreements for shared use or alliances, not outright sales of sovereign land. European powers, conversely, interpreted them as permanent cessions. Maps from this period illustrate the steady encroachment: land "purchased" or "ceded" through dubious means, often under duress, carving away ancestral domains piece by piece. The vast territories of nations like the Lenape or Powhatan, once extending across entire regions, were progressively reduced to smaller and smaller parcels.

II. The Indian Removal Act and the Trail of Tears (1830s): This period represents one of the most brutal chapters in American history and a defining moment in the Native American "diaspora." The Indian Removal Act of 1830 authorized the forced relocation of southeastern Indigenous nations (the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole, collectively known as the "Five Civilized Tribes") from their ancestral lands in the southeastern United States to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma).

Maps charting the Trail of Tears are profoundly moving. They depict the original homelands in Georgia, Tennessee, Alabama, and Florida, overlaid with the forced routes of thousands of men, women, and children marching westward, often in chains, through harsh conditions, leading to the deaths of thousands. These maps starkly contrast "before" and "after," showing rich agricultural lands in the East abandoned for unfamiliar territories hundreds of miles away. This was not a voluntary migration but a government-orchestrated ethnic cleansing, profoundly scattering communities and severing ancient ties to sacred sites and burial grounds.

III. The Reservation System (Late 19th Century): As westward expansion continued, driven by Manifest Destiny, the remaining Indigenous lands were consolidated into reservations. Maps of the late 19th and early 20th centuries show the proliferation of these isolated, often desolate, parcels of land. The reservation system was designed to contain, control, and ultimately assimilate Indigenous peoples, breaking their connection to traditional lifeways and governance.

These maps illustrate a checkerboard pattern across the American West, where vast tribal territories were reduced to small, often non-contiguous "reserves." The Great Sioux Nation’s lands, for instance, once encompassing millions of acres, were systematically broken up into smaller reservations like Pine Ridge, Rosebud, and Standing Rock, with significant portions opened to non-Native settlement. This forced confinement, far from ancestral hunting grounds and ceremonial sites, constituted another form of internal displacement, profoundly impacting Indigenous identity and economic self-sufficiency.

Maps as Acts of Reclamation: Identity, Sovereignty, and Resilience

Despite centuries of dispossession and attempts at cultural eradication, Indigenous nations have not only survived but thrived, adapting and reclaiming their narratives. Modern maps, especially those created by Indigenous communities themselves, are powerful tools for asserting identity, sovereignty, and a renewed connection to ancestral lands.

I. Reasserting Sovereignty and Land Claims: Contemporary maps reflecting Native American lands often highlight the boundaries of federally recognized reservations, illustrating the ongoing legal and political status of tribal nations as sovereign entities within the United States. These maps are crucial for understanding tribal governance, jurisdiction, and the complex interplay between tribal, state, and federal law. Beyond official reservation boundaries, Indigenous cartography also emphasizes traditional use areas, sacred sites, and areas of historical significance that extend far beyond current legal definitions. The "Land Back" movement, for example, utilizes maps to visualize ancestral territories and advocate for the return of Indigenous lands.

II. Cultural Preservation and Language Revitalization: For many Indigenous nations, identity is inextricably linked to specific geographical features—mountains, rivers, forests—that hold cultural and spiritual significance. Maps depicting traditional place names (toponymy) in Indigenous languages are vital for language revitalization efforts. They reconnect younger generations with the landscape through the linguistic lens of their ancestors, preserving oral histories and cultural narratives tied to specific locations. For example, a Navajo map might not just show Diné Bikeyah (Navajo Nation), but also label specific mesas and canyons with their Diné names, each carrying a story or a teaching.

III. Digital Cartography and Indigenous Voices: The advent of Geographic Information Systems (GIS) and digital mapping technologies has empowered Indigenous communities to create their own maps, offering counter-narratives to colonial cartography. Interactive online maps, often developed by tribal cultural resource departments or Indigenous scholars, can layer historical information with contemporary land use, environmental data, and cultural sites. These digital platforms allow Indigenous voices to shape the representation of their own territories, showcasing their deep knowledge of the land, their traditional ecological practices, and their ongoing stewardship. They become living documents, constantly updated with new research, oral histories, and community input.

Navigating with Respect: A Call for Travelers and Learners

For anyone interested in responsible travel and a deeper understanding of American history, engaging with the "map of Native American diaspora" is not merely an academic exercise; it’s an ethical imperative.

I. Understand the Landscape’s Layers: When you travel across North America, recognize that the seemingly pristine landscapes or bustling cities often sit atop ancestral Indigenous lands. Use resources like Native Land Digital to identify the traditional territories you are visiting. This simple act of acknowledgment is a powerful step towards recognizing Indigenous presence.

II. Visit Tribal Museums and Cultural Centers: Many tribal nations operate museums, cultural centers, and heritage sites that offer invaluable insights into their history, art, and contemporary life. These institutions provide a platform for Indigenous voices to share their stories on their own terms. Learning directly from Indigenous people about their maps, their history of displacement, and their enduring identity fosters genuine understanding and respect.

III. Support Indigenous Economies and Sovereignty: Recognize that tribal nations are sovereign governments. When you visit or engage with Indigenous communities, be mindful of their laws, customs, and economic initiatives. Support Indigenous artists, businesses, and cultural events. Understanding the maps of their past and present empowers you to be a more informed and respectful ally in their ongoing struggles for self-determination and justice.

Conclusion

The "map of Native American diaspora" is a powerful, multifaceted narrative. It begins with the vibrant tapestry of pre-colonial nations, traces the devastating lines of colonial conquest and forced removal, and culminates in the dynamic, self-determined maps created by Indigenous communities today. These maps are not static historical relics but living documents that illustrate the profound human cost of displacement, the incredible resilience of Indigenous cultures, and the unyielding connection to ancestral lands that continues to shape identity. By engaging with these maps, we not only uncover hidden histories but also contribute to a more just and informed future, one where the enduring presence and sovereignty of Native American nations are recognized, respected, and celebrated. For the discerning traveler and lifelong learner, exploring these maps is an essential journey into the heart of North America’s true story.