Beyond Borders: Unveiling Native American History and Identity Through Cultural Education Maps

Maps are more than mere navigational tools; they are powerful narratives, windows into history, culture, and identity. For Indigenous peoples across North America, maps are especially potent, serving as crucial instruments in the ongoing effort to reclaim historical narratives, preserve cultural heritage, and assert sovereignty. This article explores the profound significance of Native American cultural education maps, offering a deep dive into their historical context, the identities they represent, and their vital role in both historical education and responsible travel.

The Canvas of Time: What Are Native American Cultural Education Maps?

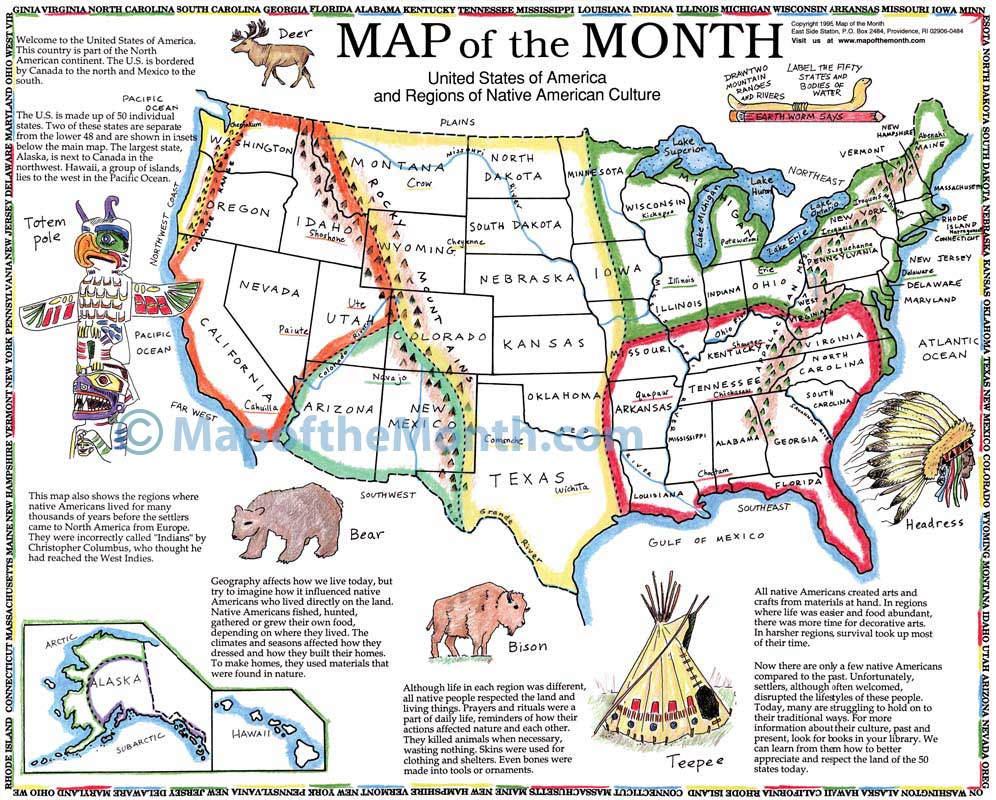

Native American cultural education maps differ fundamentally from conventional political maps. While a typical map might delineate modern state lines or national borders, Indigenous maps often depict ancestral territories, linguistic groups, migration routes, sacred sites, trade networks, and resource-gathering areas that existed long before European contact and continue to hold significance today. These are not static, fixed boundaries in the colonial sense, but fluid, dynamic representations of relationships with land, water, and fellow beings that have evolved over millennia.

These maps are multi-layered, often illustrating:

- Pre-Contact Territories: Showing the vast and diverse lands occupied by hundreds of distinct nations, often overlapping and demonstrating shared usage or historical alliances.

- Linguistic Families: Grouping tribes by their shared language roots, highlighting the immense linguistic diversity that once thrived and is now being revitalized.

- Migration Routes and Trade Networks: Tracing the movements of peoples and the intricate systems of exchange that connected distant communities.

- Sacred Sites and Cultural Landscapes: Pinpointing places of spiritual importance, ceremonial grounds, and areas where human interaction has shaped the environment over generations.

- Treaty Lands and Reservations: Documenting the complex and often broken agreements made with colonial powers and the resultant, much smaller, land bases designated for tribes.

- Contemporary Tribal Lands and Communities: Reflecting the current geography of sovereign nations, their jurisdictional areas, and ongoing land claims.

![]()

Unlike maps imposed by external powers, Native American cultural education maps are often developed by Indigenous communities themselves, reflecting their own knowledge systems, oral traditions, and perspectives. They are living documents, constantly being updated and interpreted to serve educational, cultural, and political purposes.

A Historical Imperative: Reclaiming Narratives

The history of Native Americans has long been distorted or erased in mainstream narratives. Colonial maps frequently depicted North America as terra nullius—empty land awaiting European discovery and settlement—ignoring the sophisticated societies, intricate land management practices, and vibrant cultures that had thrived for thousands of years. Native American cultural education maps directly challenge this erasure, providing irrefutable evidence of ancient presence and profound connection to the land.

Consider the impact of depicting the vast territories of the Lakota, Navajo, Cherokee, or Iroquois Confederacy before European encroachment. These maps immediately convey the scale and complexity of Indigenous civilizations, countering the myth of nomadic, primitive peoples. They highlight:

- Sovereignty and Self-Determination: By illustrating ancestral domains, these maps underscore the inherent sovereignty of Indigenous nations that predates the formation of the United States and Canada. They are visual arguments for treaty rights and self-governance.

- The Trauma of Forced Removal: Maps tracing the "Trail of Tears," the Long Walk of the Navajo, or the forced relocation of countless other tribes vividly illustrate the devastating impact of colonial expansion. They transform abstract historical events into tangible journeys of immense suffering and resilience. Showing the original homelands alongside the reduced reservation lands tells a powerful story of loss and survival.

- Broken Treaties: Many maps specifically outline the areas promised to tribes through treaties—agreements often violated by colonial governments. These maps become legal and historical documents, demonstrating the ongoing injustices and the basis for modern land claims and reparations. They serve as a constant reminder of unfulfilled obligations.

- Resilience and Persistence: Despite centuries of warfare, disease, and assimilation policies, Native American cultures endure. The modern component of these maps—showing current tribal lands, cultural centers, and revitalized language programs—testifies to an extraordinary resilience and a determination to preserve identity against overwhelming odds.

These maps are not just about showing where things happened; they are about showing who was there, what they knew, and how they endured. They are a powerful tool for decolonization, allowing Indigenous peoples to tell their own stories on their own terms.

Identity and Belonging: The Land as Teacher

For Indigenous peoples, identity is inextricably linked to the land. The land is not merely property; it is a relative, a teacher, a source of spiritual power, and the repository of ancestral memory. Native American cultural education maps visually represent this profound connection.

- Place Names and Language: Indigenous maps often feature original place names, which are not just labels but encapsulate entire stories, ecological knowledge, and historical events. Learning these names is a crucial step in language revitalization and reconnecting with ancestral knowledge. A river might be named not just for its physical characteristics, but for the sacred ceremonies performed there or the specific fish it provides at certain times of the year.

- Ancestral Homelands as Cultural Blueprints: The specific geographical features of a tribe’s ancestral lands—mountains, rivers, deserts, forests—have shaped their worldview, their ceremonies, their art, and their way of life. Maps that highlight these features allow for a deeper understanding of cultural practices. For example, a map showing traditional hunting grounds for a Plains tribe or traditional fishing territories for a Northwest Coast tribe directly informs their cultural practices.

- Spiritual and Ceremonial Sites: Many maps include locations of sacred sites, demonstrating the deep spiritual connection to the land. These sites are often central to ceremonies, storytelling, and the transmission of traditional knowledge. They are places where the spiritual and physical worlds converge, and their preservation is vital to cultural continuity.

- Collective Memory and Belonging: By seeing their ancestral lands depicted, individuals and communities reinforce their sense of belonging and their shared heritage. These maps help to bridge the gap between past and present, ensuring that future generations understand their roots and their responsibilities to the land and their ancestors. They are a visual affirmation of who they are and where they come from.

- Sovereignty and Stewardship: The maps reinforce the idea that Indigenous nations have a rightful claim and a sacred responsibility to be stewards of their traditional lands, even those areas now within modern political boundaries. This concept of land stewardship is a core component of Indigenous identity and environmental philosophy.

In essence, these maps illustrate that Indigenous identity is not an abstract concept; it is geographically rooted, culturally expressed, and historically informed by the very landscapes depicted.

Beyond Static Lines: Dynamic Cultural Landscapes

One of the most powerful aspects of Native American cultural education maps is their ability to convey dynamism rather than static boundaries. Traditional Indigenous land use was often seasonal, migratory, and shared, reflecting sophisticated ecological knowledge and resource management.

- Seasonal Round Maps: These maps illustrate how tribes moved across their territories throughout the year, following animal migrations, harvesting different plant resources, and adapting to environmental cycles. This contrasts sharply with the European concept of fixed, year-round property ownership.

- Trade Routes and Interconnectedness: Ancient trade routes, depicted on maps, reveal a vast network of intertribal communication, exchange of goods, and shared cultural practices that spanned the continent. This demonstrates a sophisticated pre-colonial economy and diplomacy.

- Ecological Knowledge: Embedded within these maps is invaluable ecological knowledge. The locations of specific plants, animal migration paths, water sources, and geological features reveal centuries of intimate understanding of the environment, a knowledge system critical for sustainable living.

- Cultural Landscapes: The maps help us understand the concept of "cultural landscapes," where the environment itself is shaped by human interaction, storytelling, and spiritual beliefs. A mountain is not just a geological formation; it’s a character in a creation story, a provider of medicinal plants, and a site for vision quests.

These dynamic maps teach us that Indigenous relationships with land were not about drawing lines on a piece of paper, but about living in harmony with the natural world, understanding its rhythms, and passing that knowledge down through generations.

Practical Applications for Travel and Education

For travelers and educators alike, Native American cultural education maps are indispensable tools for fostering a deeper understanding and promoting respectful engagement.

For Travelers:

- Ethical Engagement: Before visiting a region, consulting these maps helps travelers identify the traditional lands of the Indigenous peoples there. This knowledge encourages respectful behavior, such as acknowledging traditional territories, seeking permission for certain activities, and understanding local protocols. Websites like Native Land Digital are excellent starting points.

- Deeper Appreciation: Knowing the historical and cultural significance of the land transforms a casual visit into a profound learning experience. A scenic vista becomes a sacred site, a forest path a traditional hunting trail, or a river a vital trade route.

- Supporting Indigenous Tourism: Many Native American nations operate cultural centers, museums, and tourism businesses on their lands. Using these maps to identify and visit these sites directly supports tribal economies and self-determination, ensuring that tourism benefits Indigenous communities.

- Challenging Stereotypes: Engaging with accurate historical maps and information helps dispel harmful stereotypes and fosters a more nuanced understanding of Indigenous cultures, moving beyond romanticized or outdated depictions.

For Educators:

- Comprehensive Historical Education: These maps are essential for teaching a more complete and accurate history of North America, one that includes Indigenous perspectives and challenges colonial narratives. They can be used to illustrate historical events, territorial changes, and the impact of policies like the Dawes Act.

- Cultural Sensitivity and Awareness: Integrating Indigenous maps into curriculum helps students develop cultural sensitivity, recognize the diversity of Native American nations, and appreciate the richness of Indigenous cultures.

- Promoting Critical Thinking: Analyzing different types of maps (colonial vs. Indigenous) encourages students to think critically about who creates maps, why they are created, and whose perspectives they represent or omit.

- Language and Environmental Education: Maps featuring traditional place names can be used in language revitalization efforts, while those depicting resource use and cultural landscapes can inform environmental studies, highlighting Indigenous stewardship practices.

Museums, universities, and tribal cultural centers are increasingly using these maps as central components of their educational outreach, offering interactive exhibits and digital platforms that bring this rich history to life.

Challenges and the Path Forward

Despite their immense value, the creation and dissemination of Native American cultural education maps face challenges. Historical records can be incomplete, oral traditions are sometimes sensitive or proprietary, and the mapping process itself requires significant resources and expertise. Furthermore, ongoing land disputes and the need to protect culturally sensitive information mean that not all traditional knowledge can or should be publicly mapped.

However, the future is bright. Indigenous communities are leading the charge in developing sophisticated mapping projects, leveraging GIS technology, and integrating traditional ecological knowledge with modern cartography. These efforts are crucial for:

- Empowerment: Giving Indigenous communities control over their own representations of land and history.

- Reconciliation: Fostering understanding and truth-telling between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples.

- Preservation: Documenting vital cultural and historical information for future generations.

- Advocacy: Providing powerful visual evidence for land claims, resource protection, and treaty rights.

Conclusion

Native American cultural education maps are far more than geographical diagrams; they are profound testaments to resilience, identity, and enduring connection to the land. They challenge conventional historical narratives, illuminate the spiritual and cultural depth of Indigenous peoples, and offer invaluable lessons in ecological stewardship. For anyone seeking to genuinely understand the history of North America, to travel respectfully, or to contribute to a more just and informed future, engaging with these maps is not just an educational opportunity—it is a moral imperative. By looking beyond the lines drawn by colonizers and embracing the rich, complex narratives embedded in Indigenous maps, we begin to see the world, and its true history, with new eyes.