The Unseen Map: Navigating Native American Court Systems and the Enduring Spirit of Sovereignty

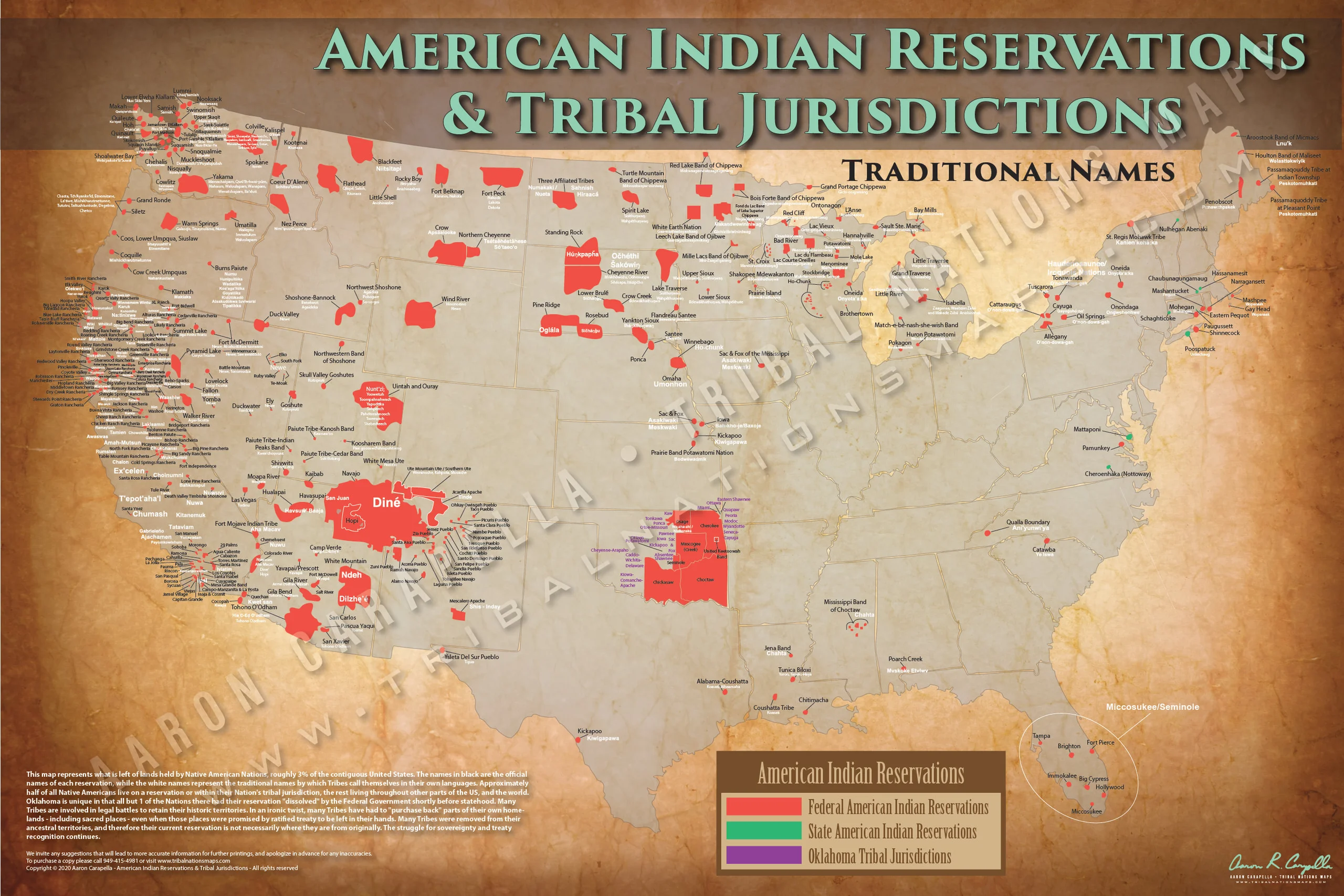

Beyond the lines on a conventional map that delineate states and counties, there exists a complex, dynamic, and profoundly significant legal landscape: the map of Native American court systems. This isn’t a static drawing, but a living testament to the enduring sovereignty, identity, and resilience of over 574 federally recognized Native American tribes within the United States. For travelers seeking a deeper understanding of American history and for educators aiming to illuminate the intricate layers of governance, comprehending these tribal judiciaries is not merely academic; it is essential for respectful engagement and a true appreciation of Indigenous self-determination.

The Foundation: Inherent Sovereignty and Distinct Legal Systems

To understand Native American court systems, one must first grasp the concept of tribal sovereignty. This is not a right granted by the United States government, but an inherent governmental authority that predates the formation of the United States. From time immemorial, Native nations exercised their own forms of justice, dispute resolution, and law enforcement, rooted in their unique cultures, traditions, and spiritual beliefs. When the United States was formed, it recognized these nations through treaties, which, though often violated, fundamentally acknowledged their distinct governmental status.

Today, this inherent sovereignty manifests in tribal governments, which, like federal and state governments, typically comprise executive, legislative, and judicial branches. Tribal courts are the judicial arm of these sovereign nations, exercising jurisdiction over their citizens and, in many cases, over activities within their territorial boundaries, often referred to as "Indian Country." These courts are not merely extensions of the federal or state systems; they are distinct legal entities that apply tribal law, which can be a blend of traditional customs, codified statutes, and constitutional provisions.

The diversity among these systems is immense. Some tribal courts operate with structures mirroring state or federal courts, complete with formal dockets, judges with law degrees, and appellate processes. Others may incorporate more traditional forms of justice, such as peacemaking circles, elders’ councils, or restorative justice practices focused on community healing and reconciliation rather than purely punitive measures. This variation reflects the rich cultural tapestry of Native America itself, where each tribe maintains its unique traditions and approaches to justice.

The Jurisdictional Labyrinth: A "Checkerboard" of Authority

The most challenging aspect for outsiders to grasp, and often for legal professionals themselves, is the intricate web of jurisdiction that characterizes Indian Country. This isn’t a simple division of power; it’s a dynamic, often overlapping, and historically contingent arrangement that creates a "checkerboard" effect, where who has authority can depend on the location, the nature of the crime or dispute, and the tribal affiliation (or lack thereof) of those involved.

1. Tribal Criminal Jurisdiction:

Historically, tribal courts held broad criminal jurisdiction over all persons within their territories. However, a series of landmark Supreme Court cases and federal legislative acts significantly curtailed this.

- Major Crimes Act (1885): Following the Ex Parte Crow Dog (1883) decision which upheld tribal jurisdiction, Congress passed this act, granting federal courts jurisdiction over certain enumerated major felonies (e.g., murder, rape, arson) committed by Native Americans in Indian Country. This was a significant erosion of tribal sovereignty.

- Oliphant v. Suquamish Indian Tribe (1978): This pivotal Supreme Court case ruled that tribal courts do not possess inherent criminal jurisdiction over non-Native Americans, even for crimes committed on tribal land. This created a jurisdictional vacuum, as state governments generally also lack criminal jurisdiction over non-Natives for crimes committed against Natives on tribal land (unless Congress grants it). This decision left many tribal communities vulnerable, as non-Native perpetrators of crimes on reservations could often escape justice.

- Duro v. Reina (1990) and Congressional Response: The Supreme Court initially ruled that tribes also lacked criminal jurisdiction over non-member Native Americans. However, Congress swiftly responded with the Duro Fix (codified in the Indian Civil Rights Act), affirming tribal criminal jurisdiction over all Native Americans, regardless of tribal membership, for crimes committed in Indian Country.

- Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) Reauthorization (2013 & 2022): In a significant restoration of tribal sovereignty, Congress amended VAWA to allow tribal courts to exercise criminal jurisdiction over non-Native perpetrators of domestic violence, dating violence, and certain other crimes (like sexual assault, stalking, and child abuse) against Native Americans within their reservations. This was a direct response to the Oliphant decision’s negative impact on public safety in Indian Country.

2. Tribal Civil Jurisdiction:

Generally, tribal courts retain broad civil jurisdiction over disputes arising within their territories, regardless of the parties’ ethnicity. This includes matters like divorce, child custody (with the crucial involvement of the Indian Child Welfare Act, or ICWA), contract disputes, property issues, and torts. This is particularly vital for preserving tribal cultural norms and protecting vulnerable tribal members.

3. Public Law 280 (PL-280):

Enacted in 1953, PL-280 was a federal law that transferred criminal and, in some cases, civil jurisdiction over certain matters in Indian Country from the federal government to specific states (California, Minnesota, Nebraska, Oregon, Wisconsin, and later Alaska). Other states could opt into PL-280. This policy, part of the disastrous "termination era," further complicated jurisdiction, as it subjected tribal members in these states to state law and courts without their consent, often leading to a loss of tribal governmental authority and resources. While some tribes have retroceded from PL-280, its legacy continues to impact jurisdiction in these states.

In essence, if a crime occurs in Indian Country, the question of who has jurisdiction (tribal, federal, or state) depends on:

- The location (on fee simple land vs. trust land).

- The nature of the crime (major felony vs. misdemeanor).

- The ethnicity/tribal affiliation of the perpetrator and the victim.

- Whether the tribe is in a PL-280 state.

This jurisdictional maze means that a simple traffic stop on a reservation might be handled by tribal police and court, while a murder involving the same individuals could fall under federal jurisdiction, and a crime committed by a non-Native against another non-Native on non-Indian fee land within a reservation might fall under state jurisdiction.

Historical Context: From Self-Governance to Assimilation and Back

The current map of tribal court systems is a direct result of centuries of interaction, conflict, and policy shifts between Native nations and the United States.

Pre-Contact: Native nations had sophisticated, diverse legal systems. Justice was often restorative, focused on maintaining harmony within the community.

Early Treaty Era (Late 1700s – Mid-1800s): Treaties formally recognized tribal sovereignty, but increasing U.S. expansionism began to erode it.

Reservation Era and Assimilation (Late 1800s – Early 1900s): Policies aimed at "civilizing" Native Americans led to the creation of "Courts of Indian Offenses" by the federal government, often staffed by non-lawyer tribal members under federal supervision. These courts were designed to suppress traditional practices and enforce U.S. norms, stripping tribes of genuine self-governance over justice. The Dawes Act (1887) further fragmented tribal lands and communities.

Termination and Relocation (1940s – 1960s): This era saw the U.S. government attempt to dissolve its relationship with tribes, ending federal recognition and services. PL-280 was a product of this policy. It was devastating, leading to immense poverty and cultural loss for terminated tribes.

Self-Determination Era (1970s – Present): A paradigm shift began with the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975. This policy recognized the failure of assimilation and termination, empowering tribes to rebuild their governments and take control of their own affairs, including justice systems. This period saw a resurgence of tribal courts, the development of tribal law codes, and the training of tribal judges and legal professionals. The Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) of 1978, which prioritizes placing Native children with Native families in foster care and adoption, is a crucial example of federal recognition of tribal sovereignty in family matters.

Identity and Cultural Preservation Through Justice

For Native American tribes, their court systems are far more than mere legal institutions; they are vital organs of cultural preservation and identity. They provide a mechanism for:

- Upholding Traditional Values: Many tribal laws are infused with traditional principles, promoting community responsibility, respect for elders, and restorative practices that aim to heal individuals and the community rather than simply punish.

- Protecting Children: ICWA ensures that tribal courts have jurisdiction over child welfare cases involving Native children, protecting them from being separated from their culture and kinship ties. This is a direct response to historical practices that forcibly removed Native children from their families.

- Preserving Language and Ceremonies: Court proceedings may incorporate tribal languages, traditional oaths, or ceremonial elements, reinforcing cultural identity within a formal setting.

- Empowering Self-Governance: The ability to administer justice is a core function of any sovereign nation. Tribal courts are tangible proof of self-determination, allowing tribes to address internal issues in ways that reflect their unique needs and values, rather than having external systems imposed upon them.

- Addressing Historical Trauma: By providing culturally relevant justice, tribal courts can play a role in healing the intergenerational trauma caused by centuries of colonialism, forced assimilation, and injustice.

Why This Matters for Travelers and Educators

For anyone traveling through or learning about Native American lands, understanding the map of tribal court systems is paramount for several reasons:

- Respecting Sovereignty: It acknowledges and respects the governmental authority of Native nations. Just as one would respect the laws of any foreign country, visitors to Indian Country should understand and adhere to tribal laws and regulations.

- Informed Engagement: Knowing about jurisdictional complexities helps travelers understand why certain services or laws might differ on a reservation compared to an adjacent county. It fosters an informed perspective, moving beyond simplistic views of "reservations" to appreciating them as distinct nations.

- Challenging Stereotypes: Learning about sophisticated tribal justice systems directly counters outdated and harmful stereotypes that depict Native Americans as lacking governance or legal order. It highlights the strength and adaptability of Indigenous institutions.

- Supporting Self-Determination: By recognizing and understanding these systems, travelers and educators indirectly support the ongoing efforts of tribes to exercise their sovereignty, protect their cultures, and build stronger, safer communities.

- Deepening Historical Understanding: The evolution of tribal courts is a microcosm of the broader history of Native American-U.S. relations, illustrating periods of conflict, assimilation, and ultimately, a powerful resurgence of self-governance.

The map of Native American court systems is not just a series of legal boundaries; it is a profound narrative etched in the land and the hearts of its people. It tells a story of enduring sovereignty, the struggle for justice against immense odds, and the unwavering commitment to cultural identity. For those who seek to truly understand the fabric of the United States, engaging with this unseen map is an indispensable journey into the living history and vibrant present of Native America. It is an invitation to look beyond the superficial and appreciate the profound depth of Indigenous nationhood.