Whispers Across the Land: Decoding the Ancient Map of Native American Communication Methods

Imagine a continent teeming with hundreds of distinct nations, each with its own language, customs, and territory. How did these diverse peoples, often separated by vast distances and formidable landscapes, communicate not just within their communities but across tribal lines, for trade, diplomacy, warning, and celebration? The answer lies in a sophisticated, multi-layered "map" of communication methods, far more intricate and profound than simple spoken words. This isn’t a geographical map of routes, but a conceptual one charting the ingenuity, cultural depth, and enduring identity embedded in how Native Americans shared information and meaning. For the modern traveler and history enthusiast, understanding this map offers an unparalleled journey into the heart of Indigenous cultures.

Directly, let’s explore the rich tapestry of Native American communication, weaving together historical context, cultural identity, and the practical genius behind these ancient systems.

1. The Living Libraries: Oral Traditions, Storytelling, and Oratory

At the very core of Native American communication lies the power of the spoken word, not merely as a tool for daily interaction but as a sacred vessel for history, law, spirituality, and identity. Oral traditions were the original libraries, meticulously preserved and transmitted through generations.

Historical Context: Before the arrival of Europeans, and for centuries after, the vast majority of Native American societies relied exclusively on oral transmission. This wasn’t a deficit; it was a highly developed art form. Elders, designated storytellers, and spiritual leaders were the custodians of vast bodies of knowledge, including creation myths, tribal histories, genealogies, moral lessons, and intricate ceremonial instructions.

Identity & Impact: These stories weren’t just entertainment; they defined who a people were. They established a community’s place in the cosmos, explained their relationship to the land, outlined social norms, and recounted the deeds of ancestors, fostering a powerful sense of collective identity and continuity. Through epic narratives, children learned their people’s values, history, and responsibilities. The Navajo Blessingway, for example, is not just a ceremony but a complex narrative cycle that restores balance and harmony, defining Navajo identity and their relationship with the universe. Similarly, the Iroquois Great Law of Peace, a foundational constitution uniting multiple nations, was transmitted orally for generations before being recorded.

Oratory was another highly esteemed form of spoken communication. Council meetings, treaty negotiations, and inter-tribal diplomacy relied on eloquent speakers who could articulate complex ideas, persuade, and build consensus. The ability to speak powerfully and thoughtfully was a mark of leadership and wisdom, shaping political landscapes and forging alliances across vast territories.

2. The Universal Handshake: Plains Sign Language (PSL)

One of the most remarkable innovations in inter-tribal communication was Plains Sign Language (PSL), sometimes called Plains Indian Sign Language (PISL) or Hand Talk. This wasn’t a collection of simple gestures but a fully developed, independent language with its own grammar and syntax.

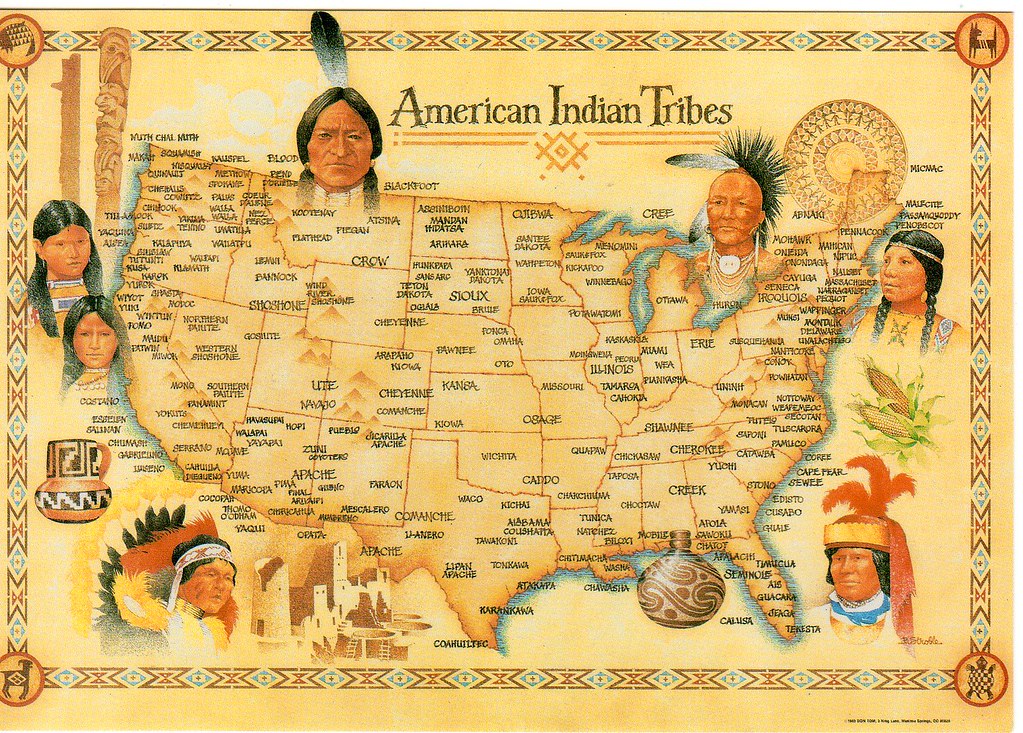

Historical Context: The Great Plains were a crossroads of diverse linguistic families (Siouan, Algonquian, Caddoan, Uto-Aztecan, Athabaskan, Kiowa-Tanoan, etc.). With over 30 distinct spoken languages spoken across the Plains, direct verbal communication between tribes was often impossible. PSL emerged as a pragmatic solution, allowing for seamless communication for trade, hunting, diplomacy, and even storytelling among groups speaking mutually unintelligible languages. It likely developed over centuries, reaching its zenith in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Identity & Impact: PSL facilitated an unprecedented level of interaction across tribal boundaries, fostering a shared identity among Plains peoples despite their linguistic differences. It was crucial for negotiating peace, forming alliances against common enemies, and coordinating massive buffalo hunts that were vital to survival. A Kiowa warrior could converse fluently with a Crow trader or a Cheyenne diplomat. This shared language became a symbol of Plains culture itself, a testament to adaptability and ingenuity. Today, PSL is still used by some Native Americans, a living legacy of inter-tribal unity.

3. Art as Archive: Petroglyphs, Pictographs, Wampum, and Winter Counts

Native Americans also developed sophisticated visual communication systems that served as enduring records, spiritual expressions, and historical archives.

Petroglyphs and Pictographs: These ancient forms of rock art, found across the continent, are visual narratives etched (petroglyphs) or painted (pictographs) onto stone surfaces.

- Historical Context: Dating back thousands of years, these images depict everything from spiritual visions, astronomical events, hunting scenes, and historical battles to territorial claims and directional markers. Sites like Newspaper Rock in Utah or the hundreds of panels in Canyon de Chelly, Arizona, offer glimpses into the lives and beliefs of ancient peoples.

- Identity & Impact: These visual messages are direct links to the past, preserving cultural memory and spiritual connections to specific landscapes. They are declarations of presence and identity, marking sacred places or recounting pivotal events for future generations. For many tribes, these sites remain sacred, embodying the spirits of their ancestors.

Wampum Belts: Primarily used by Northeastern Woodlands tribes, particularly the Iroquois Confederacy and Algonquian nations, wampum beads (made from quahog and whelk shells) were woven into intricate belts.

- Historical Context: Wampum served as currency in some contexts, but its primary role was as a mnemonic device and ceremonial object for recording treaties, laws, historical events, and important messages. The patterns and colors of the beads held specific meanings. For instance, the Hiawatha Belt symbolizes the unity of the five nations of the Iroquois Confederacy.

- Identity & Impact: Wampum belts were tangible manifestations of agreements and historical truths. They embodied the word of a nation, symbolizing its integrity and identity. When a treaty was made, the wampum belt was exchanged, serving as a permanent record and a reminder of mutual obligations. To "read" a wampum belt was to recall and recite the history and laws it represented, ensuring that knowledge was passed down accurately.

Winter Counts: Predominantly used by Plains tribes like the Lakota, Kiowa, and Mandan, winter counts were annual pictorial calendars that recorded the most significant event of each year.

- Historical Context: Typically painted on buffalo hides, muslin, or paper, a single pictograph or ideogram represented an entire year, from first snow to first snow. A tribal historian (or "keeper of the count") would narrate the story associated with each image, providing a chronological history of the community.

- Identity & Impact: Winter counts were vital historical documents, preserving the collective memory and identity of a tribe. They tracked major events like battles, epidemics, environmental changes, and important cultural ceremonies, offering a unique Indigenous perspective on history. They connected generations by providing a shared narrative of the past, reinforcing tribal identity and resilience.

4. Signals of Distance: Drums, Flutes, and Smoke

Beyond direct interaction, Native Americans employed methods to communicate across greater distances, utilizing sound and visual cues from the environment.

Drums: The drum is a sacred instrument across many Native American cultures, central to ceremonies, dances, and social gatherings.

- Historical Context: While not a complex "language" like Morse code, specific drum patterns and rhythms could convey information over distances. For example, a particular rhythm might signal the start of a ceremony, the approach of visitors, or a call to gather.

- Identity & Impact: The drumbeat is often described as the heartbeat of the people, connecting individuals to their community, their ancestors, and the spiritual world. It fosters a sense of unity and shared identity during communal events.

Flutes: Native American flutes, typically made from wood or cane, were used for personal expression, courtship, and spiritual practices rather than long-distance communication.

- Historical Context: The haunting melodies of the flute were often played by young men during courtship, to express emotions, or in solitary moments of contemplation.

- Identity & Impact: Flute music is deeply personal and reflective, connecting the individual to their inner self and the natural world. It represents a form of spiritual communication and emotional expression, contributing to the rich tapestry of cultural identity.

Smoke Signals: Often romanticized in popular culture, smoke signals were indeed employed by some Native American tribes, primarily for short-distance, pre-arranged communication.

- Historical Context: They weren’t complex messages but rather alerts: "presence," "danger," "gathering," or "all clear." Their efficacy depended on clear visibility and a shared understanding of specific smoke patterns (e.g., number of puffs, density, duration), making them more of a localized alarm system than a broad communication network. Fires were built in specific locations, and blankets or hides were used to create controlled puffs of smoke.

- Identity & Impact: This practical application, rather than myth, reveals a sophisticated understanding of environmental conditions and strategic information sharing. It speaks to a collective vigilance and a coordinated response system vital for community safety and organization.

5. Linguistic Diversity: The Spoken Word’s Unparalleled Richness

It is crucial to remember that there is no single "Native American language." North America was and still is home to hundreds of distinct Indigenous languages, belonging to numerous language families.

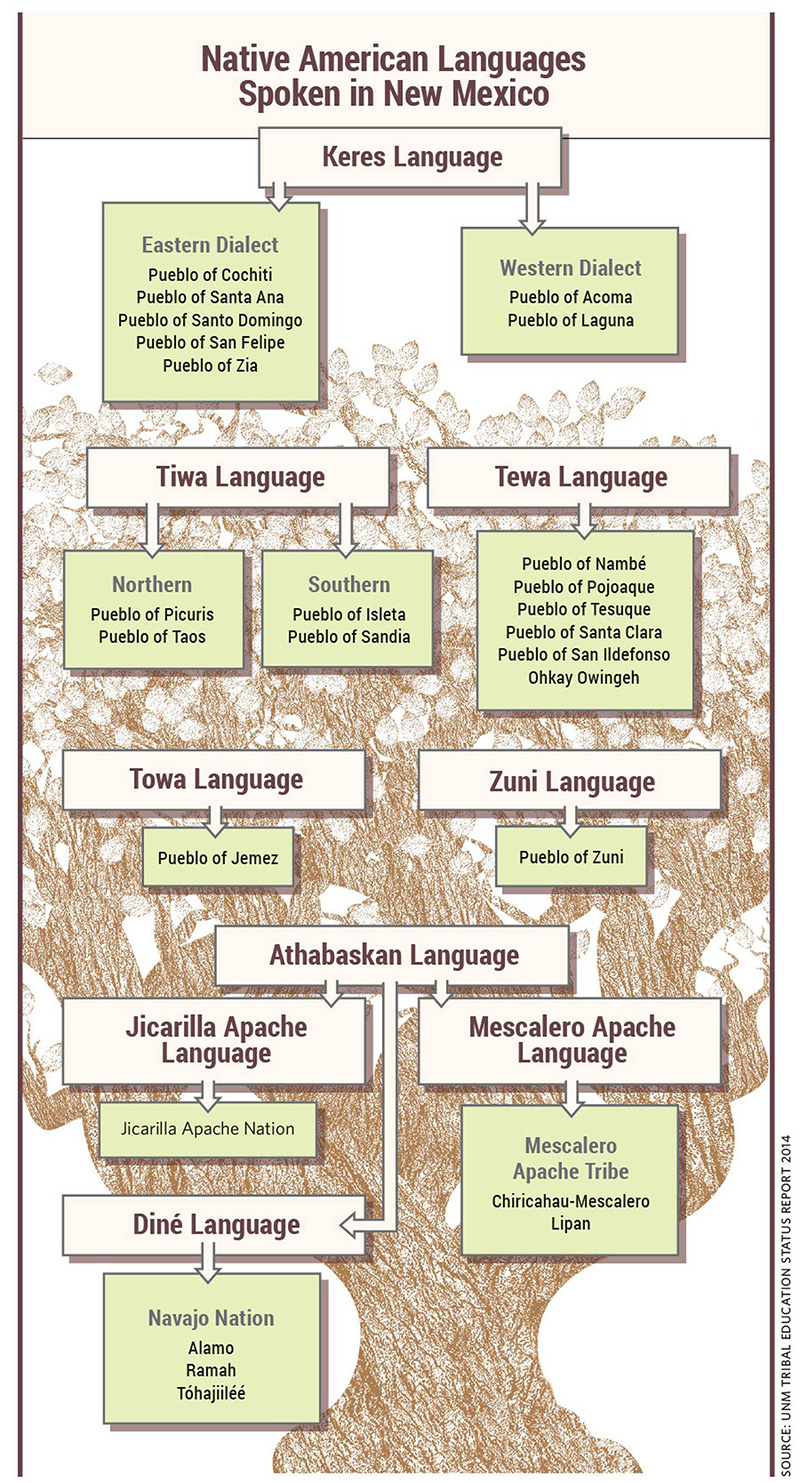

Historical Context: Before European colonization, there were an estimated 300-500 distinct languages spoken north of Mexico. These languages are as diverse from each other as English is from Chinese or Arabic. Major language families include Algonquian (e.g., Cree, Ojibwe, Blackfoot), Siouan (e.g., Lakota, Dakota, Crow), Uto-Aztecan (e.g., Hopi, Ute, Comanche), Athabaskan (e.g., Navajo, Apache), Iroquoian (e.g., Mohawk, Cherokee), and many more, including numerous language isolates (languages with no demonstrable relationship to others).

Identity & Impact: Each language is a unique worldview, a complete system for understanding and interacting with the world. It encodes a people’s history, their philosophies, their relationship with the land, and their social structures. For instance, many Indigenous languages have verb-heavy structures that emphasize processes and relationships over static nouns, reflecting a dynamic, interconnected understanding of existence. The loss of a language is the loss of an irreplaceable repository of knowledge, culture, and identity.

Today, many tribes are engaged in heroic efforts to revitalize their languages, understanding that language is a foundational pillar of their identity and sovereignty. These efforts involve immersion schools, master-apprentice programs, and the creation of new media in Indigenous languages.

Conclusion: The Enduring Map of Understanding

The "map" of Native American communication methods is not a static artifact but a dynamic, living testament to human ingenuity, cultural depth, and resilience. From the nuanced narratives of oral tradition to the universal gestures of Plains Sign Language, the enduring records of rock art and wampum, and the vast diversity of spoken languages, Indigenous peoples developed sophisticated systems to connect, share, and preserve their unique identities.

For the modern traveler, understanding this complex map transforms a simple visit to a historical site into an immersive journey through time and culture. It challenges romanticized stereotypes and reveals the profound intelligence and adaptability of Native American societies. It invites us to listen more closely, look more deeply, and appreciate the incredible richness of human expression that thrived across this continent long before it was ever called America. This map, ultimately, is a guide not just to communication methods, but to a deeper understanding of Indigenous peoples themselves – their history, their identity, and their enduring legacy as masterful communicators and cultural architects.