Lines of Conflict, Rivers of Resilience: Mapping Native American Colonial Wars

Maps are more than mere navigational tools; they are historical documents, political statements, and often, silent witnesses to immense human drama. When we examine maps depicting the colonial wars involving Native American tribes, we are not simply looking at shifting borders or battle lines. We are confronting centuries of conflict, resilience, loss, and the enduring struggle for identity and sovereignty. These maps unveil an unfolding drama where Indigenous nations, each with distinct cultures, languages, and territories, faced relentless pressure from expanding European and later American powers. For the history enthusiast and the thoughtful traveler, understanding these maps offers a profound, often sobering, journey into the true foundations of North America.

The Pre-Colonial Tapestry: A Continent Already Mapped

Before the arrival of Europeans, North America was not a "wilderness" but a continent intricately understood and managed by hundreds of diverse Indigenous nations. Their maps were not always drawn on parchment; they were etched in memory, sung in oral traditions, carved into wood, or woven into textiles. These "mental maps" detailed ancestral hunting grounds, trade routes, sacred sites, resource locations, and the boundaries of allied and rival nations. They reflected sophisticated understandings of ecology, geography, and inter-tribal relations.

The initial European maps, often crude and speculative, reflected an ignorance of this complex reality, frequently labeling vast, populated areas as terra nullius – empty land. This cartographic erasure laid the ideological groundwork for conquest, allowing colonial powers to claim territories already inhabited, already mapped in Indigenous minds, and already governed by Indigenous laws. Understanding this pre-existing Indigenous cartography is crucial because it highlights that the colonial wars were not fought over empty land, but over a continent already rich in history, culture, and sovereign nations.

Early Encounters and the First Lines of Conflict (16th-17th Centuries)

The earliest colonial maps began to sketch out European claims along the coasts, depicting nascent settlements alongside vast, undifferentiated "Indian territories." Spanish entradas into the Southwest, French forays into the Great Lakes and Mississippi Valley, and English settlements along the Atlantic seaboard inevitably led to clashes. These early conflicts were often localized, driven by resource competition, misunderstandings, and the devastating impact of European diseases, which decimated Indigenous populations and destabilized existing power structures.

Maps from this period might show the early Virginia colonies locked in conflict with the Powhatan Confederacy, or Spanish missions attempting to assert control over Pueblo lands. What these maps don’t always show, but what history reveals, are the complex alliances Indigenous nations formed, sometimes with Europeans against traditional rivals, sometimes against the encroaching Europeans. The Pequot War in New England (1636-1638), for instance, was a brutal conflict that saw English colonists, aided by Mohegan and Narragansett allies, decimate the Pequot nation. Maps produced afterward began to show Pequot lands absorbed into colonial holdings, a stark visual representation of a devastating defeat and the beginning of a pattern of dispossession.

Imperial Rivalries and Indigenous Geopolitics (18th Century)

The 18th century saw European imperial rivalries – primarily between Britain and France – spill over into North America, fundamentally altering the landscape of Indigenous relations and warfare. The French and Indian War (1754-1763), known globally as the North American theater of the Seven Years’ War, was a seismic event. Maps of this era reveal a continent fiercely contested not just by European powers, but by powerful Indigenous confederacies like the Iroquois, Huron, Algonquin, Cherokee, and Shawnee, who often played a sophisticated geopolitical game, aligning with one European power against another to protect their own interests and territories.

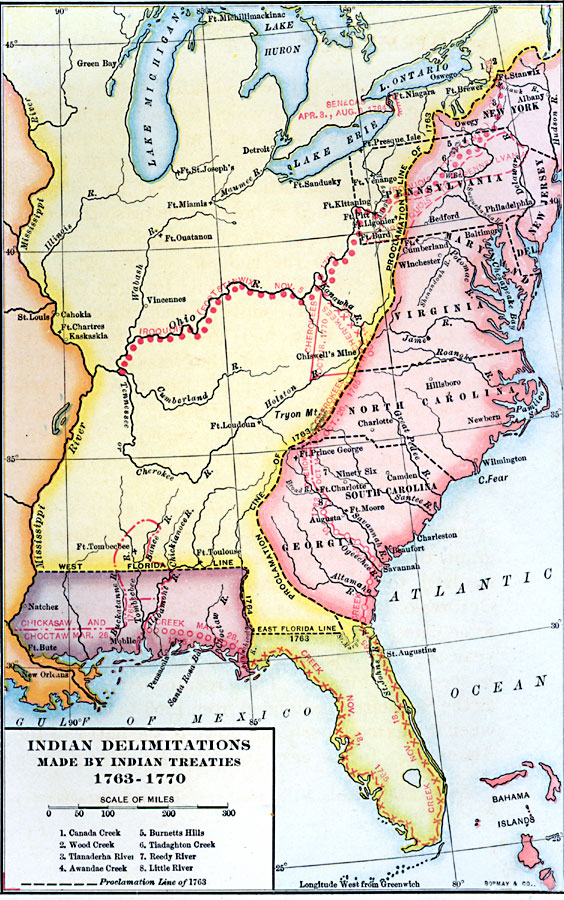

Maps from this period illustrate strategic forts built by both sides, trade routes, and areas of control. The Ohio Valley, a critical fur-trading region and a gateway to the interior, became a flashpoint. Indigenous nations, recognizing the existential threat posed by either British or French dominance, fought valiantly to maintain their independence. Pontiac’s War (1763-1766), which erupted in the wake of British victory and their perceived arrogance, saw a pan-tribal confederacy attempt to drive the British out of the Great Lakes region. Maps charting the widespread attacks on British forts and settlements demonstrate the power and coordination of this Indigenous resistance, even if ultimately unsuccessful in preventing British expansion.

The Proclamation Line of 1763, drawn by the British Crown along the Appalachian Mountains, was a significant cartographic moment. It aimed to prevent colonial settlement west of the line, ostensibly to protect Indigenous lands and prevent further conflict. While often viewed as a temporary measure by colonists, for many Indigenous nations, it represented a recognition of their territorial rights, however fleeting. This line became a source of intense friction between colonists hungry for land and the British government, foreshadowing the American Revolution.

The American Revolution and the Era of Dispossession (Late 18th – Early 19th Centuries)

The American Revolution (1775-1783) placed Indigenous nations in an impossible position. Caught between two warring European-descended powers, many tribes allied with the British, seeing them as the lesser of two evils or as defenders of the Proclamation Line against land-hungry American settlers. The Iroquois Confederacy, for example, was tragically split, with the Mohawk, Seneca, Cayuga, and Onondaga largely siding with the British, while the Oneida and Tuscarora sided with the Americans. Maps of the frontier during the Revolution are crisscrossed with military campaigns, raids, and retaliatory expeditions that devastated Indigenous communities and lands, regardless of their allegiance.

The Treaty of Paris (1783), which ended the war, was a brutal betrayal for many Indigenous allies of the British. The treaty ceded vast territories, including Indigenous lands, to the newly formed United States without any consultation or consent from the Native nations who inhabited them. Maps produced by the fledgling United States immediately began to depict these lands as American territory, ignoring Indigenous sovereignty.

This era marked the beginning of a relentless push for "Indian Removal." Maps from the early 19th century begin to show the relentless westward expansion of American settlement. Figures like Tecumseh and his brother Tenskwatawa, the Shawnee Prophet, attempted to forge a pan-tribal confederacy to resist this encroachment, leading to the Battle of Tippecanoe (1811) and involvement in the War of 1812. Maps of the Great Lakes region during this period illustrate the continued Indigenous resistance, often with British support, against American expansion.

The Trail of Tears and the Cartography of Forced Migration (1830s-1850s)

The Indian Removal Act of 1830 formalized the U.S. policy of forcibly relocating Native American nations from their ancestral lands in the southeastern United States to designated "Indian Territory" (primarily present-day Oklahoma). Maps from this period are perhaps the most chillingly explicit visual records of colonial violence. They delineate the forced marches of the "Five Civilized Tribes" – the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole – along what became known as the Trail of Tears.

These maps show not just the starting and ending points, but the arduous routes themselves, often multiple paths, over thousands of miles, across rivers and mountains. Each line on these maps represents immense suffering, death from disease, starvation, and exposure, and the profound trauma of cultural uprooting. The lands left behind by these nations were quickly surveyed, divided, and opened for white settlement, visually transforming the map of the American South. The identity of these nations, intrinsically linked to their ancestral lands for millennia, was shattered and then re-forged in new, often hostile, environments.

The Plains Wars and the Final Frontier (Mid-Late 19th Century)

As the United States pursued its "Manifest Destiny" across the continent, the focus of colonial conflict shifted to the Great Plains and the American West. Maps of this period chart the routes of westward expansion – the Oregon Trail, the Santa Fe Trail, the transcontinental railroad – all cutting through the territories of powerful Plains nations like the Lakota, Cheyenne, Arapaho, Comanche, and Apache.

The Plains Wars (roughly 1850s-1890s) were a series of brutal conflicts over land, resources (especially the buffalo), and the very way of life of these nomadic and semi-nomadic tribes. Maps depict cavalry campaigns, battles like Little Bighorn (1876), the Sand Creek Massacre (1864), and the Wounded Knee Massacre (1890), which marked the tragic end of large-scale armed Indigenous resistance. Simultaneously, these maps begin to show the proliferation of "Indian Reservations" – dwindling, fragmented parcels of land carved out of vast ancestral territories. These reservations were cartographic prisons, designed to contain and control Indigenous populations, disrupting their economies, cultures, and identities.

The shift from expansive, Indigenous-controlled territories to isolated, circumscribed reservations is one of the most powerful visual narratives these maps convey. It represents the near-total triumph of colonial expansion and the profound dispossession of Native American nations.

What Maps Reveal: Identity, History, and Resilience

Examining maps of Native American colonial wars offers several profound insights:

- The Illusion of Empty Land: These maps, when properly interpreted, shatter the myth of terra nullius. They reveal that every inch of land claimed by colonial powers was already someone’s homeland, sacred ground, or hunting territory.

- Contested Sovereignty: The lines on these maps represent not just territorial claims but fundamental clashes over different concepts of land ownership, governance, and nationhood. Indigenous nations never fully ceded their sovereignty; it was often violently suppressed or unjustly negotiated away.

- The Scale of Dispossession: The progressive shrinkage of Indigenous lands and the expansion of colonial claims, vividly depicted on these maps, tells a story of unparalleled land loss and resource exploitation.

- Indigenous Agency and Resilience: While the maps undeniably show loss, they also implicitly highlight the incredible resilience and agency of Native American peoples. Despite overwhelming odds, they fought, negotiated, adapted, and survived. Their strategic alliances, military tactics, and cultural persistence are crucial, though often unstated, elements within these historical maps.

- A Foundation for Modern Identity: The historical conflicts depicted on these maps directly inform contemporary Native American identity. Land claims, treaty rights, and the fight for self-determination are rooted in the injustices and broken promises of the colonial era. The memory of ancestral lands, even if lost, remains a powerful component of tribal identity and cultural revitalization efforts.

For the Traveler and Educator: Engaging with this History

For those drawn to history and travel, engaging with maps of Native American colonial wars is an essential, if sometimes uncomfortable, experience.

- Visit Historical Sites and Museums: Many national parks, state parks, and tribal museums offer interpretive exhibits that use maps to explain these conflicts. Sites like the Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument, the Trail of Tears National Historic Trail, or museums dedicated to specific tribes provide crucial context.

- Seek Indigenous Perspectives: Look for resources, books, and online materials created by Native American scholars and communities. Their interpretations of these maps and the events they represent often differ significantly from colonial narratives.

- Understand Treaty Lands: Many contemporary maps still show reservation boundaries. Researching the history of these lands, including the treaties (often broken) that established them, provides insight into ongoing issues of sovereignty and land rights.

- Support Tribal Tourism: Where appropriate and respectful, visiting tribal lands and engaging with tribal tourism initiatives directly supports Native American communities and allows for a deeper understanding of their enduring cultures.

Conclusion

The maps of Native American colonial wars are not dusty relics; they are living documents that trace the profound transformations of a continent and its peoples. They lay bare the historical injustices of colonization, the strategic brilliance and tragic losses of Indigenous nations, and the enduring legacy of these conflicts on contemporary identity and sovereignty. For anyone seeking to understand the true, complex history of North America, these maps are an indispensable guide, urging us to look beyond the lines and see the human stories, the deep historical wounds, and the unwavering spirit of resilience that continues to shape the continent today.