The "Map of Native American Civil Rights Movement" is not a static atlas of roads and borders, but a dynamic, interwoven tapestry of places, events, and legal battles spanning centuries. It charts a continuous journey of resistance, resilience, and the relentless pursuit of sovereignty and self-determination against the backdrop of colonial expansion, forced assimilation, and systemic injustice. For a travel blog focused on historical education, understanding this map means delving into the physical sites where history was forged, and the conceptual spaces where identity was reclaimed and redefined.

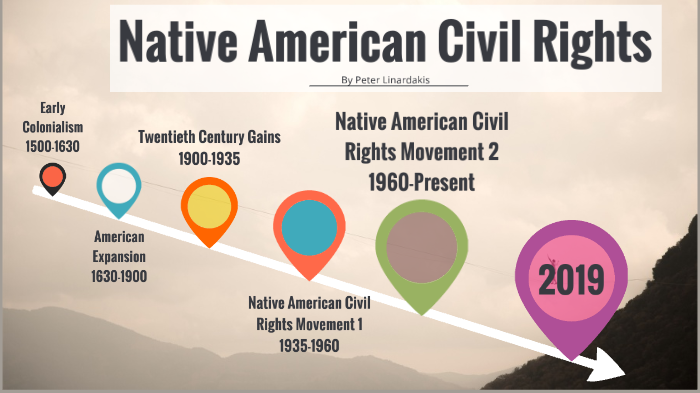

I. The Deep Roots: A Legacy of Sovereignty and Struggle (Pre-1900s to Mid-20th Century)

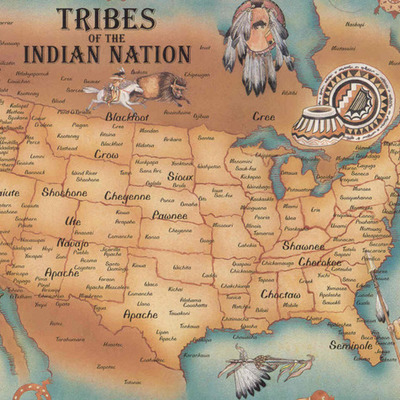

The foundational layer of this map begins long before the term "civil rights movement" entered popular lexicon. It originates with the thousands of sovereign Indigenous nations that inhabited North America for millennia, each with its own governance, culture, and territorial claims. The arrival of European powers marked the beginning of a prolonged struggle for survival and recognition. Early "civil rights" efforts were often acts of armed resistance against land encroachment and treaty violations, such as the various Plains Wars, the Seminole Wars, or the Pueblo Revolt of 1680. These conflicts, fought across vast landscapes from Florida swamps to the Western plains, represent the earliest physical manifestations of defending inherent rights.

The 19th century brought an era of forced removal, epitomized by the "Trail of Tears," where the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole nations were forcibly marched from their ancestral lands in the Southeast to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma). This brutal journey, marked by immense loss of life, etched a deep scar on the map and collective memory, symbolizing the devastating impact of federal policy on Indigenous populations. The map here is one of displacement and profound injustice, highlighting the resilience required merely to endure.

Following the era of removals and the establishment of reservations, the late 19th and early 20th centuries saw policies aimed at assimilation. Boarding schools, such as the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania or Sherman Institute in California, became notorious sites where Indigenous children were forcibly separated from their families, languages, and cultures. These institutions, spread across the country, represent a dark chapter in the map of identity suppression, yet also ironically became spaces where a pan-Indian identity began to coalesce among survivors. The struggle here was not just for physical rights, but for the very soul and identity of a people.

The Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) of 1934, while intended to reverse some assimilationist policies and promote tribal self-governance, was a mixed blessing. It often imposed foreign governmental structures on tribes and further complicated land tenure. Still, it laid some groundwork for future self-determination efforts. However, the mid-20th century brought the devastating "Termination" policy (1950s-1960s), which sought to end federal recognition of tribes and abolish reservations, and the "Relocation" program, which encouraged Indigenous people to move to urban centers like Los Angeles, Chicago, and Denver for job opportunities. These policies dispersed communities and identities, yet inadvertently created new hubs for Indigenous political organizing, as individuals from diverse tribal backgrounds found common cause in urban environments. The map expands to include urban landscapes, where a new form of activism began to simmer.

II. Igniting the Flames: The Red Power Movement (1960s-1970s)

The 1960s and 70s saw the eruption of the Red Power Movement, a direct parallel to the African American Civil Rights Movement, but distinct in its focus on tribal sovereignty, treaty rights, and cultural revitalization. This period offers some of the most iconic and geographically significant markers on the map of Native American civil rights.

-

Alcatraz Occupation (1969-1971): This barren island in San Francisco Bay, once a notorious federal prison, was occupied by "Indians of All Tribes" for 19 months. The occupiers, citing the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty which allowed Lakota to claim abandoned federal land, demanded the island be turned into an Indigenous cultural and educational center. Alcatraz became a powerful symbol of Indigenous resilience, defiance, and the demand for treaty rights. It galvanized national and international attention, inspiring other acts of Indigenous activism. Its location, a prominent landmark, made it a highly visible site of protest.

-

The Trail of Broken Treaties (1972): Following Alcatraz, a cross-country caravan of Indigenous activists, organized by the American Indian Movement (AIM) and others, traveled from the West Coast to Washington D.C. to demand a review of treaty violations and present a "Twenty Points" proposal for federal policy reform. The march culminated in the occupation of the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) building, where activists seized documents to expose corruption and misdeeds. The map here traces a physical journey across the continent, highlighting the widespread discontent and the determination to bring grievances directly to the nation’s capital, a symbolic seat of power.

-

Wounded Knee Occupation (1973): Perhaps the most dramatic and widely reported event, the 71-day occupation of Wounded Knee, South Dakota, on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, brought the struggle for sovereignty and against corruption to a head. AIM and Oglala Lakota activists seized the site, which held immense historical significance as the location of the 1890 Wounded Knee Massacre. The occupation, marked by a tense standoff with federal agents, symbolized the ongoing fight against federal oppression, the demand for justice, and the deep connection to ancestral lands and historical trauma. This site on the Great Plains became a powerful, albeit tragic, beacon of the movement.

-

Fish-Ins (Pacific Northwest): Concurrent with these larger actions, localized struggles for treaty fishing rights in the Pacific Northwest (e.g., Washington State, Columbia River) were crucial. Indigenous activists, often supported by celebrity figures like Marlon Brando, engaged in direct action, fishing in defiance of state laws that infringed upon their federally recognized treaty rights. These actions emphasized the importance of resource rights and the living nature of treaties, directly connecting specific waterways and fishing grounds to the broader civil rights map.

III. Beyond the Headlines: Sustained Activism and Legal Battles

The intensity of the Red Power era led to significant legislative changes. The Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975 marked a pivotal shift, allowing tribes to assume control over federal programs designed to serve their communities. This act, while not tied to a single physical location, fundamentally altered the map of governance, shifting power from Washington D.C. back to tribal nations across the country.

The subsequent decades have seen a continuous, often quieter, struggle in courtrooms and legislative chambers. The map here is marked by countless legal battles over:

- Land Claims: From the Black Hills of South Dakota to ancestral lands in Maine, tribes have pursued legal avenues to reclaim or receive compensation for illegally taken territories. The ongoing struggle for the Black Hills, sacred to the Lakota, highlights the spiritual and cultural dimensions of land rights.

- Water Rights: In arid regions of the Southwest and West, access to water is life. Tribes like the Navajo, Hopi, and various California tribes have fought for their inherent water rights, often against powerful agricultural and industrial interests. These battles are mapped onto specific rivers, aquifers, and irrigation systems.

- Environmental Justice: The fight against resource extraction and pollution on or near tribal lands (e.g., uranium mining on Navajo Nation, the Dakota Access Pipeline at Standing Rock in North Dakota) represents a modern extension of civil rights, linking environmental protection with cultural preservation and health. Sacred sites like Bear Ears National Monument in Utah or Oak Flat in Arizona become focal points of protest and protection, illustrating the deep spiritual connection to the land.

- Cultural Preservation: The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) of 1990 mandated the return of ancestral remains and cultural items from museums and federal agencies to their rightful tribal owners. This legislation impacts museums, universities, and federal collections across the nation, creating a conceptual map of repatriation and healing.

- Gaming Rights: The Indian Gaming Regulatory Act of 1988 allowed tribes to operate casinos, providing a crucial source of economic development and self-sufficiency for many nations, shifting the economic map of many reservations.

IV. Identity and Cultural Resurgence: The Heart of the Movement

Throughout these struggles, the reclamation and celebration of Indigenous identity have been paramount. The map of civil rights is incomplete without recognizing the thousands of sites where cultural revitalization takes place:

- Language Immersion Schools: From Hawaii to Oklahoma, tribal communities are establishing schools to teach endangered Indigenous languages to new generations, ensuring the survival of unique worldviews.

- Tribal Colleges and Universities: Over 30 tribal colleges and universities across the country serve as beacons of higher education, tailored to Indigenous perspectives and needs, fostering future leaders and scholars.

- Cultural Centers and Museums: Institutions like the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington D.C. and countless tribal museums on reservations serve as vital spaces for education, storytelling, and the preservation of heritage.

- Powwows and Ceremonial Grounds: These vibrant gatherings, held across North America, are essential for maintaining cultural practices, spiritual beliefs, and community bonds, illustrating a living, breathing map of identity.

- Art and Literature: Contemporary Indigenous artists, writers, and filmmakers are using their crafts to challenge stereotypes, assert identity, and share their stories, creating a cultural landscape that pushes boundaries and educates broader audiences.

V. Mapping the Future: Ongoing Struggles and the Path Forward

The map of Native American civil rights continues to evolve. Contemporary issues include:

- Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women (MMIW): This crisis, impacting communities across the US and Canada, has led to a grassroots movement demanding justice and systemic change, drawing attention to a map of vulnerability and violence.

- Voting Rights: Efforts to ensure equitable access to voting for Indigenous communities, especially in remote areas, remain a vital part of the civil rights agenda.

- Representation: The fight for accurate and respectful representation in media, education, and politics continues, aiming to dismantle harmful stereotypes and promote understanding.

- Climate Change: Indigenous communities, often on the front lines of climate change impacts, are leading efforts for environmental justice and sustainable practices, linking their ancestral lands to global ecological concerns.

Conclusion: Engaging with the Map

For the educational traveler, understanding the "Map of Native American Civil Rights Movement" is an invitation to engage with a profound and ongoing narrative. It encourages moving beyond superficial tourism to truly appreciate the depth of Indigenous history, the resilience of its peoples, and the continuing fight for justice and self-determination.

This map is not merely a collection of historical markers; it is a living document. When visiting a reservation, a cultural center, or a historical site like Alcatraz or Wounded Knee, travelers are not just witnessing history; they are engaging with the enduring spirit of nations that have fought, and continue to fight, for their inherent rights. It calls for respectful engagement, active listening, and a commitment to learning from the past to foster a more just future. This journey across the physical and conceptual landscape of Indigenous civil rights is a powerful reminder that sovereignty and identity are not given; they are continually asserted, defended, and celebrated.