The Invisible Cartography: Mapping Native American Citizenship Rights, History, and Identity

Understanding the "Map of Native American Citizenship Rights" isn’t about tracing lines on a conventional atlas. It’s an intricate, evolving cartography woven from centuries of treaties, legislation, court decisions, and the enduring resilience of indigenous peoples. This map isn’t static; it pulses with history, delineates spheres of sovereignty, and profoundly shapes the identity of Native Americans today. For any traveler or student of history seeking to truly grasp the fabric of North America, comprehending this complex landscape is not just educational—it’s essential.

Before the arrival of European powers, hundreds of distinct Native nations governed vast territories, each with its own intricate systems of law, governance, and citizenship. These were sovereign peoples, whose identity was inextricably linked to their land, culture, and communal bonds. European contact initially saw these nations treated, at least on paper, as foreign powers capable of entering into treaties. Early colonial powers, and later the nascent United States, often negotiated land cessions and alliances as if dealing with sovereign entities. However, this recognition was fleeting and often opportunistic, quickly giving way to policies of subjugation, removal, and assimilation.

The foundational shift in the relationship between Native nations and the United States began to crystalize in the early 19th century. Landmark Supreme Court cases, particularly Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (1831) and Worcester v. Georgia (1832), established the concept of Native tribes as "domestic dependent nations." This legal doctrine, while affirming a degree of inherent sovereignty, also positioned tribes as wards of the federal government, subject to federal oversight but not directly to state laws. This was a critical distinction, as it began to delineate a unique status for Native Americans within the nascent American legal framework—a status that was neither fully foreign nor fully citizen.

This period also saw the implementation of devastating policies like the Indian Removal Act of 1830, which forcibly relocated thousands of Native people from their ancestral lands in the southeastern United States to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma). The Trail of Tears is a stark reminder of how federal power was wielded to dispossess and displace, fundamentally altering the spatial and political map of Native America. Reservations were established, often on marginal lands, further isolating tribes and subjecting them to federal control, yet paradoxically preserving a communal land base that would later become crucial for the assertion of tribal sovereignty.

The late 19th century brought another seismic shift: the Allotment Era, primarily through the Dawes Act of 1887. Driven by a misguided belief that private land ownership would "civilize" Native Americans and integrate them into mainstream American society, this act broke up communal tribal lands into individual allotments. Any "surplus" land was then sold off to non-Native settlers. The Dawes Act was catastrophic, resulting in the loss of nearly two-thirds of the remaining Native American land base between 1887 and 1934. Critically, those who accepted allotments and adopted "habits of civilized life" were theoretically granted US citizenship. However, this was a hollow citizenship, often without full voting rights or the protection of the law, and came at the cost of tribal identity and land. This era underscored that even when citizenship was offered, it was frequently conditional and designed to dismantle, rather than empower, Native communities.

Despite these efforts to assimilate, the question of comprehensive Native American citizenship remained largely unresolved. The 14th Amendment, ratified in 1868, declared that "all persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States." However, this clause was widely interpreted to exclude most Native Americans living on reservations, who were deemed to be under the jurisdiction of their tribal governments rather than the full jurisdiction of the United States. While some Native Americans gained citizenship through specific treaties, military service (especially after World War I), or marriage to a non-Native citizen, the vast majority remained non-citizens of the United States, even as their lands and lives were increasingly dictated by federal policy.

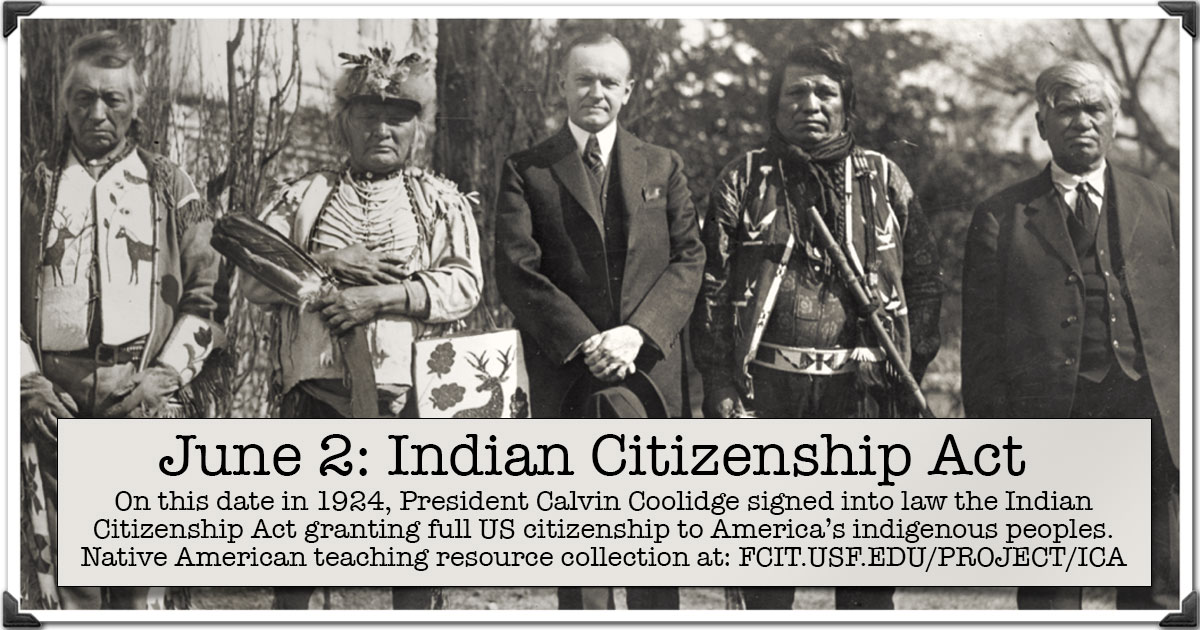

The true turning point arrived with the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924. This landmark legislation granted full US citizenship to all Native Americans born within the territorial limits of the United States. It was a momentous achievement, a recognition that after centuries of occupation, displacement, and assimilation attempts, Native peoples were undeniably part of the American nation. However, this act was not without its complexities. It was passed without consulting many tribal leaders, and some viewed it as another federal imposition, while others saw it as a long-overdue right. Crucially, the ICA did not extinguish tribal citizenship; it established a dual citizenship, allowing Native Americans to be citizens of both their tribal nation and the United States. This dual identity remains a cornerstone of Native American life today.

Yet, the "map of rights" did not become universally equitable overnight. Even after 1924, many states continued to deny Native Americans the right to vote through discriminatory practices such as poll taxes, literacy tests, and residency requirements, or by simply claiming that those living on reservations were "wards of the state" and thus ineligible. It wasn’t until the late 1940s that states like Arizona and New Mexico finally granted Native Americans unrestricted voting rights. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 further strengthened these protections, but even today, challenges related to voter access and representation persist in many Native communities.

The Indian Citizenship Act also did not diminish tribal sovereignty. Instead, it highlighted the unique legal and political status of Native nations. The map of Native American citizenship rights today is deeply intertwined with the concept of tribal sovereignty. Each of the over 574 federally recognized tribes in the United States maintains its own government, laws, and judicial systems. These nations have the inherent right to determine their own membership (tribal citizenship), manage their lands and resources, establish their own courts, and regulate economic activity within their borders. This means that for a Native American person, their rights and responsibilities can vary depending on whether they are on tribal land, the specific laws of their tribe, and the complex web of federal and state laws that apply.

For instance, criminal jurisdiction on reservations is a particularly complex area, often creating a multi-layered legal landscape. Major crimes might fall under federal jurisdiction, while minor crimes involving only tribal members might be handled by tribal courts. If a non-Native person commits a crime against a Native person on tribal land, state jurisdiction might be invoked, or federal depending on the crime. This patchwork quilt of jurisdiction is a direct legacy of the "domestic dependent nation" status and the evolving legal frameworks.

Identity for Native Americans is thus multifaceted and profoundly shaped by this unique legal and historical journey. Being a US citizen does not erase one’s identity as a citizen of the Navajo Nation, the Cherokee Nation, or the Lakota Oyate. Instead, it adds a layer of belonging and responsibility. Native identity is rooted in ancestral lands, language, cultural practices, spiritual beliefs, and the communal bonds of their tribe. It is an identity forged through centuries of resistance, adaptation, and resilience in the face of immense pressure to assimilate.

Travelers visiting Native American lands will immediately encounter this distinct identity. Tribal flags fly alongside the US flag, tribal police enforce tribal laws, and cultural centers celebrate unique histories. Understanding that these are not merely "ethnic groups" but sovereign nations with inherent rights and a distinct legal status is crucial. It’s an invitation to engage with a vibrant, living history, to recognize the ongoing struggles for self-determination, and to appreciate the rich tapestry of cultures that continue to thrive.

The "map" of Native American citizenship rights is ultimately a conceptual one, charting not geographical boundaries alone, but also layers of legal jurisdiction, historical injustices, and the enduring spirit of self-governance. It illustrates a journey from independent nations to wards of the state, through forced assimilation, and finally to a recognition of dual citizenship and affirmed tribal sovereignty. This journey is far from over. Contemporary issues such as land rights, water rights, economic development, protection of sacred sites, and the ongoing fight against systemic inequities continue to define the contours of this map. For anyone seeking to understand the United States beyond its superficial narratives, exploring this complex, dynamic map of Native American citizenship rights, history, and identity is an indispensable and enlightening endeavor. It reveals not just a part of American history, but a profound testament to the strength and endurance of indigenous cultures.