Celestial Architects: Mapping Native American Astronomical Knowledge Across Ancient Landscapes

Forget the notion of ancient peoples gazing at the stars in simple wonder. Across the vast and diverse landscapes of North America, indigenous tribes developed incredibly sophisticated systems of astronomical observation, interpretation, and application. Their knowledge wasn’t just about identifying constellations; it was deeply interwoven with their spirituality, agriculture, architecture, social structures, and very identity. This is a journey to understand the "map" of Native American astronomical knowledge – not a physical chart, but a conceptual overlay revealing centuries of profound engagement with the cosmos, etched into the land, the sky, and their enduring cultures.

The story begins with a fundamental truth: for Native American peoples, the sky was a living, breathing entity, a sacred text, and a practical guide. Unlike Western science, which often compartmentalizes knowledge, indigenous astronomy was holistic. The movements of the sun, moon, stars, and planets dictated planting and harvesting seasons, guided migrations, signaled ceremonial times, and formed the basis of complex creation stories and moral frameworks. To understand the sky was to understand the self, the community, and one’s place within the vast cosmic order.

The Southwest: Sun Daggers and Kiva Calendars

Perhaps nowhere is this astronomical prowess more evident than in the American Southwest, home to the Ancestral Puebloans (Anasazi) and their descendants like the Hopi and Zuni. Here, monumental architecture served as both dwelling and observatory.

Chaco Canyon, New Mexico: This UNESCO World Heritage site is a prime example. The "Sun Dagger" at Fajada Butte is legendary. On the summer solstice, a dagger-shaped beam of light pierces a spiral petroglyph, bisecting it precisely. On the winter solstice, two daggers frame the spiral. During the equinoxes, a single dagger pierces the center. This isn’t random; it’s a testament to meticulous observation and sophisticated engineering, demonstrating a precise understanding of the sun’s annual path.

Beyond Fajada Butte, many of Chaco’s great houses – massive multi-story structures like Pueblo Bonito and Chetro Ketl – are aligned with celestial events. Kivas, circular underground ceremonial chambers, often feature precise alignments to solstices and equinoxes, functioning as both sacred spaces and calendrical devices. Casa Rinconada, a great kiva, has doorways and niches that align with the cardinal directions and the summer and winter solstices, facilitating the tracking of the solar year for agricultural and ceremonial purposes. This astronomical knowledge was crucial for managing their complex agricultural society in a harsh desert environment.

Mesa Verde, Colorado: Further west, the cliff dwellings of Mesa Verde, while less overtly astronomical in their structure than Chaco, still show an awareness of solar patterns. Many dwellings are oriented to maximize solar gain in winter and provide shade in summer, a practical application of solar knowledge. The Hopi, descendants of the Ancestral Puebloans, continue to maintain intricate calendrical systems based on sun-watching, where "Sun Priests" track the sun’s position along the horizon to determine the timing of critical ceremonies and agricultural activities. This living tradition demonstrates the enduring legacy of this ancient knowledge.

The Great Plains: Medicine Wheels and Star Stories

Moving northward to the vast expanses of the Great Plains, we find a different, yet equally profound, expression of astronomical understanding, particularly among tribes like the Lakota, Cheyenne, and Crow. Here, the landscape itself became the observatory, often marked by "medicine wheels."

Bighorn Medicine Wheel, Wyoming: This iconic stone structure, over 80 feet in diameter, consists of a central cairn, spokes radiating outward, and outer rings. Archaeological and archaeoastronomical studies have shown that several alignments within the wheel point to the rising positions of the summer solstice sun, as well as the rising of prominent stars like Aldebaran (in Taurus), Rigel (in Orion), and Sirius. These alignments would have served as a sophisticated calendar, marking the longest day of the year and the appearance of key stars crucial for navigation, hunting, and ceremonial timing. For Plains tribes, who followed bison herds, accurate calendrical knowledge was vital for survival and for gathering together for important rituals like the Sun Dance.

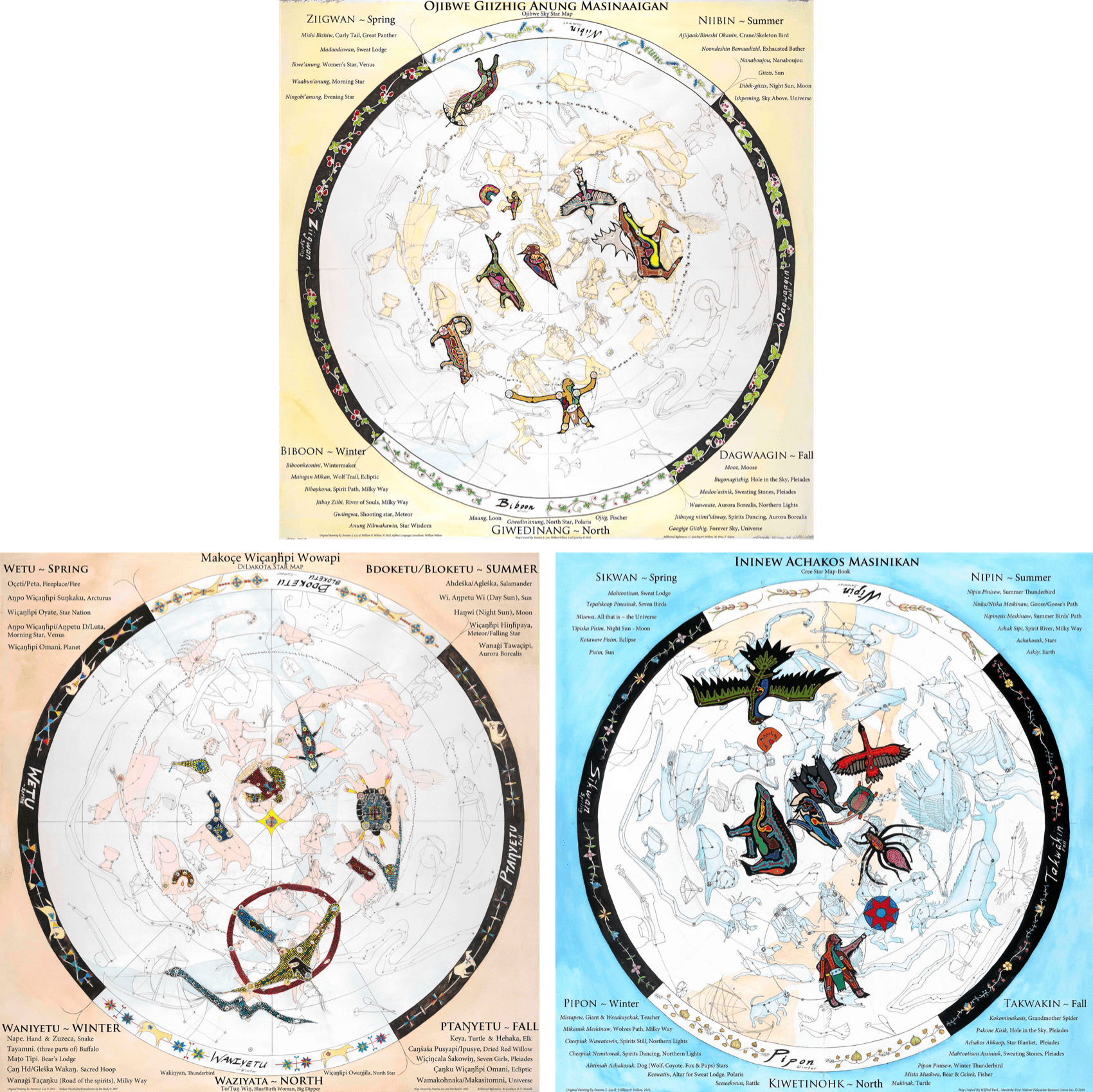

Beyond these stone structures, the celestial map was woven into the oral traditions of the Plains peoples. The Lakota, for instance, saw the Big Dipper as a "skunk" or a "hunting party." The Pleiades (the Seven Sisters) were often associated with important stories and ceremonies, sometimes seen as a cluster of lost children or powerful spirits. Their "Winter Counts" – pictographic calendars painted on hides – often recorded significant astronomical events, demonstrating a continuous, generations-long engagement with the sky. Black Elk, the famous Oglala Lakota holy man, spoke extensively of his visions and the importance of the stars, revealing a cosmic understanding that linked the individual, the community, and the universe.

The Eastern Woodlands: Woodhenges and Serpent Mounds

On the other side of the continent, the mound-building cultures of the Eastern Woodlands, such as the Hopewell and Mississippian peoples, also left behind impressive evidence of astronomical sophistication.

Cahokia Mounds, Illinois: Near modern-day St. Louis, Cahokia was the largest pre-Columbian city north of Mexico, a bustling metropolis with a population rivaling London’s at its peak. Central to its calendrical system was "Woodhenge," a series of large timber circles. Much like Stonehenge in England, these circles consisted of massive log posts, carefully placed to mark the rising positions of the sun at the solstices and equinoxes. These alignments were critical for managing Cahokia’s vast agricultural output, particularly maize cultivation, and for scheduling the elaborate ceremonies that defined Mississippian life. The construction of Woodhenge demonstrates advanced surveying techniques and a deep understanding of solar mechanics.

Serpent Mound, Ohio: This colossal effigy mound, stretching over a quarter-mile long, depicts a winding serpent. While its primary purpose is debated, archaeoastronomers have noted that the serpent’s head aligns with the summer solstice sunset, and coils along its body align with other significant solar and lunar events. This suggests a powerful connection between the serpent, a potent symbol of renewal and earth energy, and the celestial cycles, integrating landscape, mythology, and astronomy into a single, awe-inspiring monument.

Pacific Northwest and Beyond: Diverse Celestial Connections

Even in regions where monumental structures are less common, astronomical knowledge was crucial. Along the Pacific Northwest coast, tribes like the Haida and Kwakiutl tracked the moon and stars for navigation during long canoe voyages and for predicting salmon runs, vital to their sustenance. Their rich oral traditions include stories of celestial beings and the origins of constellations.

In California, various tribes used rock art and specific landscape features to mark solstices and equinoxes, often incorporating intricate pictographs that mirrored celestial phenomena. For the Navajo (Diné), the stars are integral to their concept of Hózhó (balance and harmony). Their hogans (traditional homes) are built with specific orientations, and their star stories, passed down through generations, provide moral lessons and connect them to their ancestors and the cosmos. The Pleiades (Dilyéhé) are particularly important, signifying the planting season and carrying deep cultural meaning.

The Cherokee of the Southeast also possessed a complex understanding of the stars, using them to guide planting, harvesting, and ceremonial cycles. They recognized constellations and star patterns that differed from European systems, but were equally effective for their purposes, often linked to animal figures and their rich mythological narratives.

Beyond Observation: The Integration of Knowledge

What truly sets Native American astronomical knowledge apart is its profound integration into every facet of life. It wasn’t merely a scientific pursuit; it was a spiritual endeavor, a cultural cornerstone.

- Calendrical Systems: The ability to predict seasons was paramount for agriculture, hunting, and gathering, ensuring survival and prosperity.

- Navigation: Stars provided a compass for nomadic tribes and seafaring peoples, guiding them across vast territories.

- Ceremonial Life: Solstices, equinoxes, and lunar cycles often marked the timing of major ceremonies, dances, and spiritual gatherings, reinforcing community bonds and connection to the sacred.

- Oral Traditions: Creation myths, hero journeys, and cautionary tales were often encoded with astronomical observations, preserving knowledge across generations and providing moral guidance. The stars were characters in their stories, and the sky a stage for the unfolding of cosmic drama.

- Architecture and Art: From the alignments of kivas and mounds to the symbolism in petroglyphs and pottery, astronomical motifs and principles were embedded in their material culture, making their environments resonate with cosmic meaning.

- Identity: This deep connection to the sky fostered a profound sense of place and identity. Their land was not just ground beneath their feet, but a part of a larger, interconnected cosmos. Their ancestors were the first sky-watchers, and their knowledge was a legacy passed down, defining who they were.

Identity, Resilience, and the Enduring Legacy

The arrival of European colonizers brought immense disruption. Traditional knowledge systems, including astronomy, were often suppressed, dismissed as primitive superstition, or simply lost as communities were decimated or forcibly removed from their ancestral lands. Missionaries actively discouraged indigenous practices, and the oral traditions that carried much of this knowledge were threatened.

Yet, this knowledge was not entirely extinguished. It persisted in rock art, in the memories of elders, in subtle architectural details, and in the enduring spiritual practices that went underground. Today, there is a powerful resurgence of interest and study in Native American astronomy, often termed "ethnoastronomy." Indigenous communities are actively reclaiming, revitalizing, and sharing this ancestral wisdom. Scientists, historians, and tribal members are collaborating to decipher the meanings of ancient sites, interpret oral histories, and demonstrate the sophisticated understanding that was nearly lost.

This map of Native American astronomical knowledge is a testament to human ingenuity, spiritual depth, and an enduring connection to the natural world. It reminds us that science is not exclusive to one culture or one methodology. For millennia, indigenous peoples were sophisticated observers of the cosmos, their "maps" guiding them not just across physical landscapes, but through the cycles of life, the rhythms of the universe, and the very fabric of their identity.

To truly understand the history and identity of Native America is to look up at the night sky and recognize the myriad stories, observations, and profound wisdom etched there by generations of celestial architects. It is to appreciate a holistic worldview where the stars were not distant points of light, but intimate relatives, guiding spirits, and the ultimate source of knowledge. This ancient wisdom, now being rediscovered and celebrated, offers invaluable lessons about our place in the universe and the enduring power of human connection to the cosmos.