Mapping Dispossession: How Allotment Policies Reshaped Native American Lands and Identity

Imagine a map. Not just a static representation of borders, but a living document scarred by policy, a visual chronicle of profound loss and resilient survival. This is the map that emerges when we delve into the history of Native American allotment policies in the United States. Far from a dry historical footnote, these policies, primarily enacted through the General Allotment Act of 1887 (also known as the Dawes Act), fundamentally redrew the physical and cultural landscape of Indigenous America, leaving an indelible mark on identity, sovereignty, and the very concept of land itself. Understanding this map is crucial for anyone seeking a deeper, more responsible engagement with Native American history and contemporary issues.

The Genesis of a Policy: Land Hunger Meets Assimilation

The story of allotment is rooted in the post-Civil War era, a period marked by aggressive westward expansion, insatiable land hunger, and a dominant national ideology of "Manifest Destiny." By the late 19th century, the U.S. government faced what it termed the "Indian Problem"—the continued existence of sovereign Native nations occupying vast tracts of land desired by settlers, railroads, and resource extractors. Previous policies had focused on removal to reservations, but even these designated lands were increasingly coveted.

Simultaneously, a powerful "reform" movement emerged, advocating for the assimilation of Native Americans into mainstream American society. Driven by a mix of genuine, if misguided, paternalism and thinly veiled racism, reformers believed that the "savage" Indian could be "civilized" by abandoning communal tribal life, embracing private property ownership, farming, and Christianity. The slogan "kill the Indian, save the man" encapsulated this brutal philosophy. Allotment became the perfect tool, a policy that promised to solve both the "land problem" and the "Indian problem" simultaneously.

The Dawes Act: An Act of Calculated Fragmentation

The General Allotment Act of 1887 was the legislative hammer that shattered communal land ownership. Its core mechanism was deceptively simple: instead of tribes holding land collectively, individual Native Americans would be assigned parcels of land, typically 160 acres for heads of households, 80 acres for single adults, and 40 acres for minors. These allotments were held in a 25-year "trust" period, during which the land was tax-exempt and could not be sold, ostensibly to protect Native landowners from exploitation. After the trust period, the allottee would receive a fee simple patent, making them full citizens and subject to state law and taxation.

The critical, and devastating, corollary to this policy was the declaration of "surplus" land. Once all eligible tribal members received their allotments, any remaining tribal land was deemed "surplus" by the government and opened up for sale to non-Native settlers, often at rock-bottom prices. This was the primary driver of the massive land loss that followed.

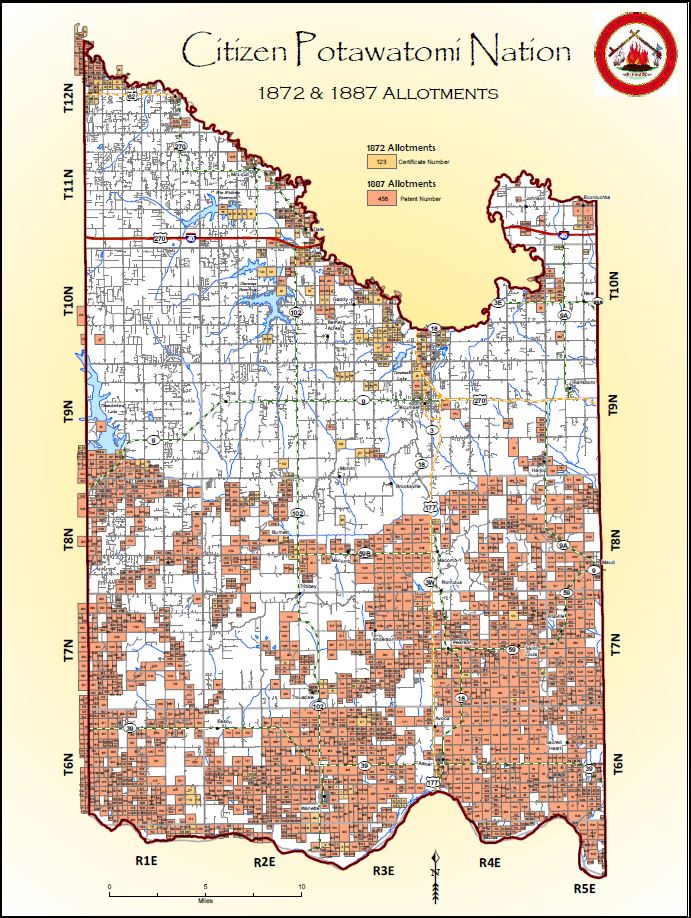

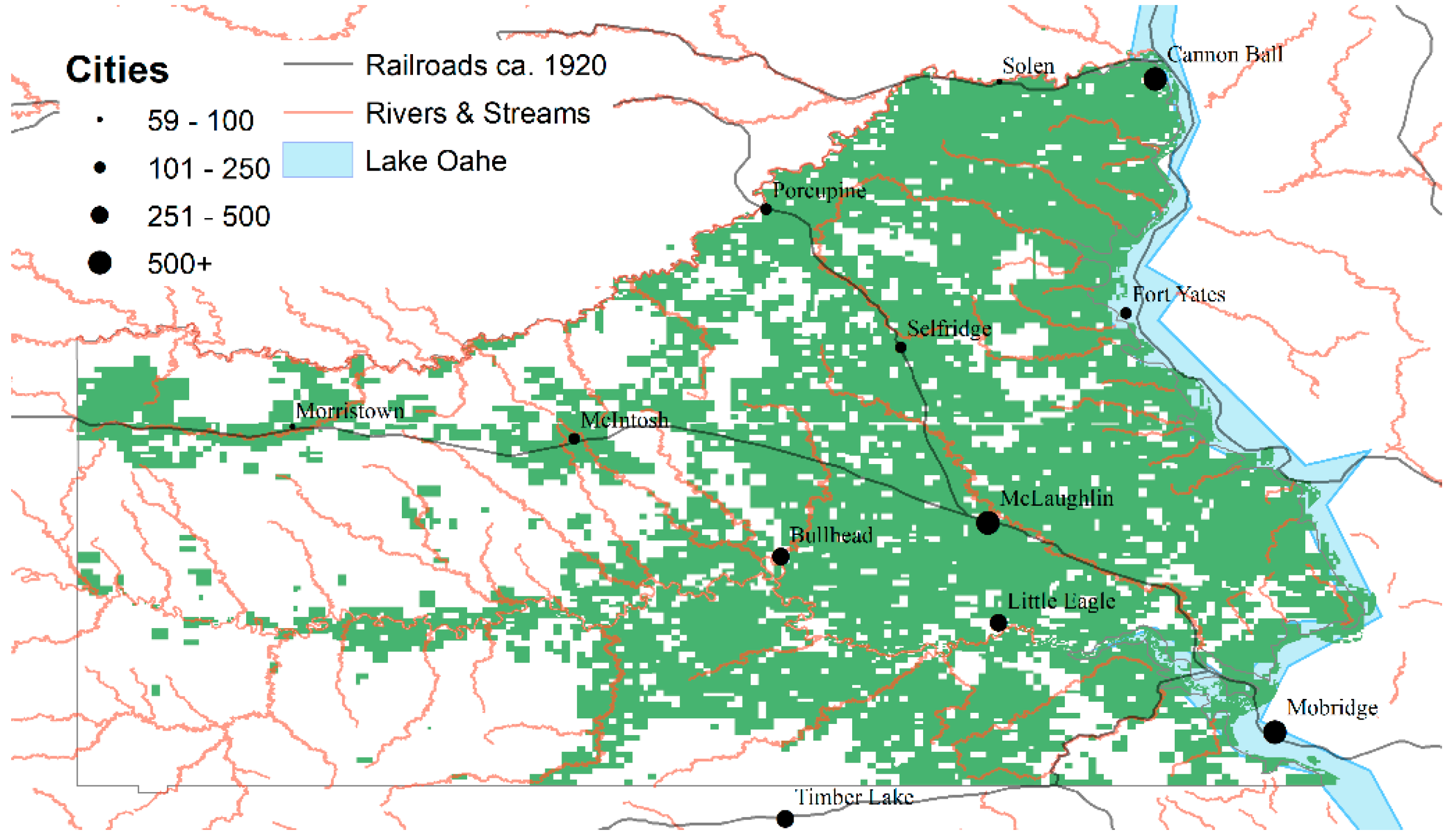

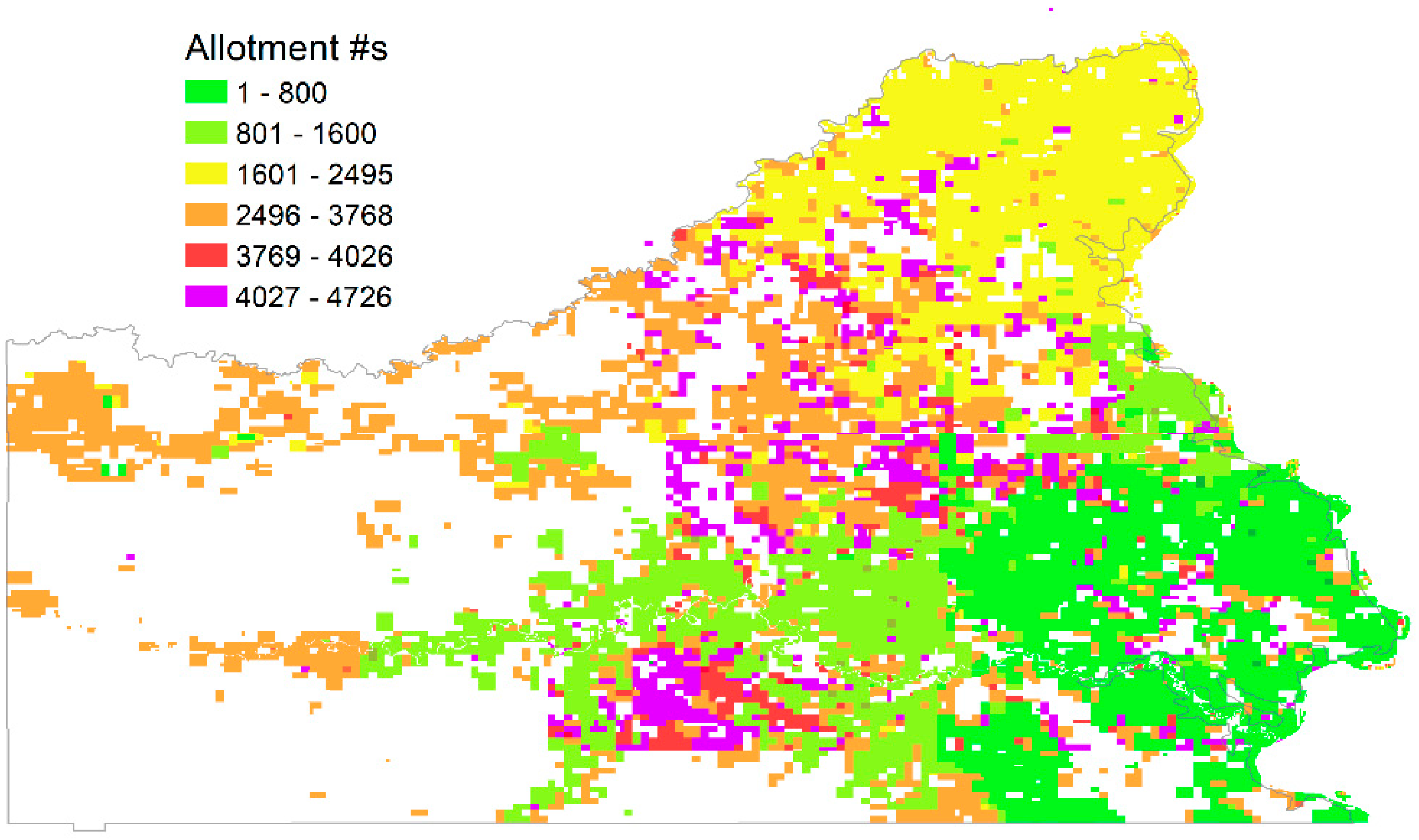

To appreciate the impact, visualize this on our map. Before Dawes, large, contiguous blocks represented tribal reservations. After Dawes, these blocks would begin to shrink, pockmarked by individual allotments, and surrounded by newly settled non-Native lands. The map would show a rapid fragmentation, a deliberate dismantling of the physical basis of tribal existence.

Mapping the Devastation: A Visual Chronicle of Loss

A map illustrating the effects of allotment policies is a stark testament to dispossession. It would depict:

-

Shrinking Reservations: The most immediate visual impact. Reservations that once spanned millions of acres were dramatically reduced as "surplus" lands were sold off. For example, the Umatilla Reservation in Oregon lost 75% of its land, while the Nez Perce in Idaho lost 90%. Across the contiguous United States, Native American landholdings plummeted from approximately 150 million acres in 1887 to just 48 million acres by 1934, a loss of nearly two-thirds.

-

The "Checkerboard" Effect: As individual allotments were assigned and "surplus" lands sold, reservations became a complex patchwork of land ownership. Some parcels remained in tribal trust, others were individually allotted and still in trust, some were fee simple lands owned by Native individuals, and many were fee simple lands owned by non-Native individuals or corporations. This "checkerboarding" created immense jurisdictional challenges, making it difficult for tribal governments to manage resources, enforce laws, and plan for economic development. Imagine trying to run a coherent government or build infrastructure when your land base is a jigsaw puzzle of different ownership and legal statuses.

-

Loss of Contiguous Territory: Traditional hunting grounds, sacred sites, and resource-rich areas that were integral to tribal economies and cultural practices were often among the "surplus" lands sold. The map would show vital connections severed, leaving tribes with fragmented territories that no longer supported their traditional ways of life or their ability to self-sustain.

-

Enclaves of Isolation: For many tribes, the remaining reservation lands became isolated islands within a sea of non-Native settlement. This isolation further exacerbated economic hardship and cultural erosion.

The map of allotment is not just a historical curiosity; it’s a foundational document for understanding the contemporary landscape of Native America, illuminating the roots of ongoing struggles over land, resources, and sovereignty.

Identity Eroded, Identity Reshaped: The Cultural Impact

The Dawes Act wasn’t just about land; it was a direct assault on Native American identity. The policy aimed to dismantle the very foundations of communal tribal life, replacing it with an individualistic, agrarian model.

-

Communal vs. Individual Ownership: For many Indigenous cultures, land was not a commodity to be owned by individuals but a sacred trust, a relative, or a communal resource. The imposition of private property rights directly contradicted these deeply held spiritual and cultural beliefs, disrupting social structures and traditional governance systems.

-

Loss of Cultural Practices: Traditional economies, often based on hunting, gathering, fishing, or nomadic pastoralism, were tied to the land. The confinement to small, individual plots, often unsuitable for farming, rendered these practices impossible. This led to the loss of vital knowledge, ceremonies, and languages linked to these activities.

-

Forced Assimilation: Allotment was accompanied by other assimilationist policies, most notably the boarding school system, which forcibly removed Native children from their families and cultures. The goal was to sever ties to tribal identity, language, and traditions, reinforcing the idea that "progress" meant becoming like white Americans.

-

Blood Quantum: To determine eligibility for allotments, the government began to formalize "blood quantum" definitions, arbitrarily categorizing individuals by percentages of Native American ancestry. This alien concept, foreign to most Indigenous societies that defined membership through kinship and cultural practice, created divisions within tribes and became a lasting, problematic legacy impacting tribal enrollment and identity to this day.

Yet, despite the immense pressures, Native identity proved remarkably resilient. While the map shows land loss, it doesn’t show the enduring spirit of the people, their continued practice of ceremonies, the clandestine passing down of languages, and the unwavering connection to their ancestral lands, even those now owned by others.

The Unintended Consequences (and Intended Ones)

While proponents claimed allotment would lift Native Americans out of poverty and integrate them into American society, the reality was catastrophic:

-

Massive Land Loss: As noted, tribes lost over 90 million acres, much of it fertile and resource-rich. This directly impoverished Native communities.

-

Poverty and Economic Disadvantage: Many allottees, unfamiliar with Anglo-American farming techniques, lacking capital, or assigned poor quality land, struggled to make a living. The trust period, meant to protect, often created dependency and prevented Native landowners from leveraging their land for economic development. When fee patents were granted, many were pressured or defrauded into selling their lands, further exacerbating poverty.

-

Fractionation and Heirship: One of the most insidious legacies of allotment is "fractionation." When an original allottee died, their land was divided among all their heirs. With each successive generation, the number of owners for a single parcel of land could multiply exponentially, leading to situations where hundreds or even thousands of individuals might own a tiny, undivided interest in a few acres. This makes land management, development, and even simple decision-making incredibly complex, hindering economic growth and perpetuating land disputes. Imagine trying to get 500 people to agree on how to use a 160-acre plot.

-

Environmental Degradation: The pressure to develop "surplus" lands and the imposition of unfamiliar agricultural practices often led to unsustainable resource extraction and environmental damage on newly opened lands.

Resistance and Resilience: Surviving the Storm

The map of allotment is also a map of resistance. Native nations did not passively accept these policies. They fought back through:

- Legal Challenges: Tribes and individual Native Americans repeatedly challenged the Dawes Act in courts, though often with limited success in the early decades.

- Political Advocacy: Native leaders organized and lobbied Congress, highlighting the devastating impact of the policies.

- Cultural Preservation: Despite intense pressure, many communities secretly maintained traditional languages, ceremonies, and governance structures, ensuring the survival of their distinct identities.

- The Meriam Report (1928): A groundbreaking government study, "The Problem of Indian Administration," unequivocally condemned the Dawes Act, revealing its disastrous social and economic consequences. This report was instrumental in shifting federal policy.

- The Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) of 1934: This landmark legislation, a direct response to the failures of allotment, ended the practice of allotment, encouraged tribal self-government, and initiated efforts to consolidate land back into tribal ownership. While not without its own complexities, the IRA marked a significant turning point towards recognizing tribal sovereignty.

The Legacy Today: A Lingering Shadow

The map of allotment continues to shape Native American life today. The "checkerboard" ownership patterns create ongoing jurisdictional nightmares, hindering law enforcement, resource management, and economic development on reservations. The problem of heirship and fractionation remains a massive challenge, with the Department of Interior estimating millions of fractional interests complicating land use.

However, the map also shows signs of hope and reclamation. Many tribes are actively working to buy back fractionated interests and "fee simple" lands within their aboriginal territories, consolidating their land base and strengthening their sovereignty. They are revitalizing languages, rebuilding economies, and asserting their inherent rights. The map is slowly, painstakingly, being redrawn by Native hands, reflecting a future built on self-determination and cultural renewal.

For the Traveler and Learner: Engaging with This History

For those exploring the landscapes of the United States, understanding the map of Native American allotment policies transforms a simple journey into a profound historical and cultural education.

- Look Beyond the Borders: When you see a modern reservation on a map, remember its history. It’s often a fraction of what it once was, and its internal boundaries are a complex legacy of allotment.

- Seek Out Native Voices: Visit tribal cultural centers, museums, and historical sites. These institutions, often run by Native communities, offer invaluable perspectives on their history, resilience, and ongoing efforts to heal from policies like allotment.

- Understand Land as Identity: Appreciate that for many Native peoples, land is not merely real estate but a sacred relative, intimately connected to identity, spirituality, and survival.

- Support Tribal Economies: Engage in responsible tourism. Buy authentic Native arts and crafts directly from tribal enterprises, dine at Native-owned businesses, and support initiatives that help tribes regain economic self-sufficiency on their lands.

- Learn About Local Tribes: Before you travel, research the Indigenous peoples whose ancestral lands you will be visiting. Learn about their history, their contemporary issues, and their efforts to reclaim their heritage.

The map of Native American allotment policies is a powerful, visual narrative of injustice and resilience. It challenges us to look beyond simplistic narratives of American history and to recognize the enduring impact of past policies on present realities. By understanding this map, we not only honor the past but also become more informed and responsible participants in shaping a more just future.