The Map of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women (MMIW) is not merely a collection of dots; it is a profound overlay on centuries of Indigenous land maps, revealing a devastating narrative of violence rooted in historical dispossession and ongoing systemic injustice. For the conscious traveler and history enthusiast, understanding this layered geography is not just an academic exercise; it is an ethical imperative, offering critical insights into the resilience of Indigenous peoples and the urgent need for action. This article delves into the profound connection between ancestral lands, colonial mapping, and the MMIW crisis, emphasizing its historical and identity-based dimensions.

The MMIW Crisis: A Stark Reality on Stolen Land

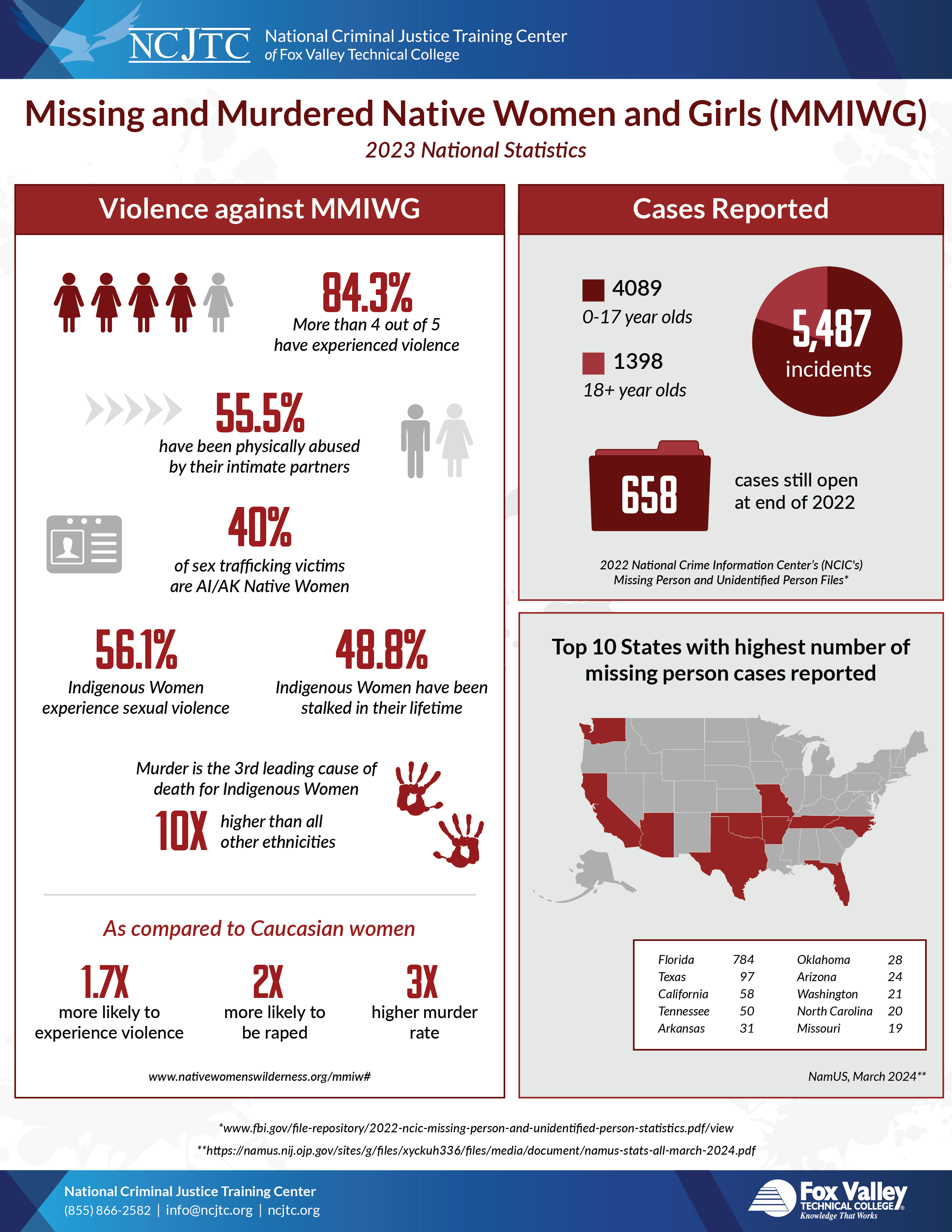

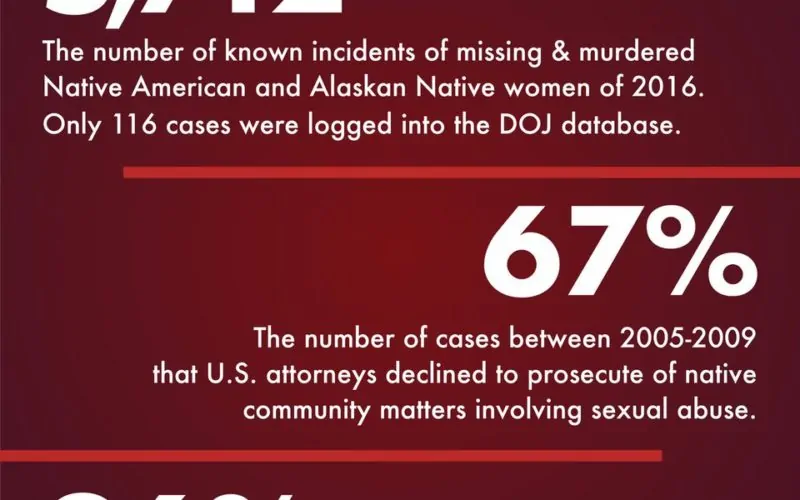

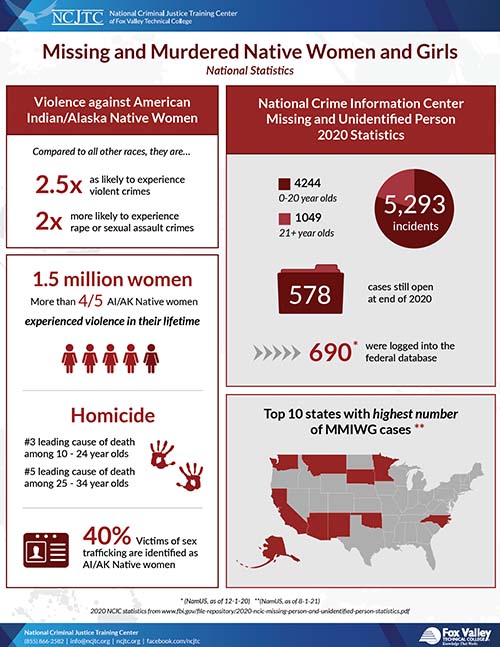

The crisis of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls, and Two-Spirit people (MMIWG2S) is an epidemic, a silent genocide unfolding across North America. Indigenous women are murdered at rates ten times higher than the national average, and often, their cases receive minimal media attention, inadequate law enforcement response, and remain unsolved. This is not a random phenomenon; it is a direct consequence of historical trauma, systemic racism, and the ongoing impacts of colonization.

When we speak of MMIW, we are not just discussing individual tragedies but a pattern of violence inextricably linked to the lands Indigenous peoples have inhabited since time immemorial. The places where Indigenous women go missing or are found murdered are often border towns adjacent to reservations, areas near resource extraction sites ("man camps"), and within communities grappling with the aftershocks of forced relocation and cultural suppression. To understand the MMIW map, we must first understand the maps that came before it: the vibrant, complex, and often contested maps of Indigenous nations.

Indigenous Land Maps: More Than Lines on Paper

Before European contact, North America was a mosaic of diverse Indigenous nations, each with its own intricate governance, spiritual practices, and deep connection to specific territories. These weren’t static, rigid borders in the European sense, but fluid, often shared, and deeply understood landscapes defined by hunting grounds, sacred sites, trade routes, and kinship ties. Maps, in this context, were not just cartographic representations; they were living narratives of identity, sovereignty, and ecological knowledge. They told stories of creation, migration, and the responsibilities humans held towards the land.

The arrival of European colonizers introduced a radically different concept of land ownership and mapping. European maps were instruments of conquest, designed to carve up the continent, impose new names, and erase existing Indigenous presence. The doctrine of terra nullius ("land belonging to no one") was used to justify the seizure of vast territories, despite the clear existence of thriving Indigenous societies. Treaties, often broken or coerced, further complicated this mapping, reducing ancestral lands to fragmented reservations—tiny islands within an encroaching colonial state.

This colonial mapping was an act of violence in itself. It severed Indigenous peoples from their traditional food sources, spiritual sites, and social structures. It disrupted trade networks, forced assimilation, and initiated a cycle of poverty and cultural erosion that continues to this day. The lands represented on these early colonial maps became battlegrounds, not just for physical territory, but for identity and survival.

The Intersecting Geographies of MMIW and Ancestral Lands

The connection between colonial land dispossession and the MMIW crisis is profound and multi-faceted. The very act of displacing Indigenous communities from their ancestral lands created the conditions for vulnerability.

-

Jurisdictional Nightmares: Reservations, often isolated and under-resourced, fall under a complex patchwork of tribal, state, and federal laws. This jurisdictional ambiguity creates dangerous gaps in law enforcement, allowing crimes to go uninvestigated and perpetrators to evade justice. When a crime occurs on a reservation, who has the authority? Often, the answer is unclear, leading to delays and inaction that disproportionately affect Indigenous victims.

-

Resource Extraction and "Man Camps": Many Indigenous communities are located near sites of extensive resource extraction—oil and gas pipelines, mining operations, logging camps. These "man camps," temporary housing for largely non-Indigenous, transient male workers, are consistently linked to increased rates of sexual assault, violence, and human trafficking against Indigenous women. The MMIW map frequently shows clusters of cases in these very regions, highlighting how the exploitation of land directly correlates with the exploitation of Indigenous bodies. This is a modern manifestation of colonial resource extraction, where both the land and Indigenous women are viewed as disposable commodities.

-

Border Towns and Racial Animus: Indigenous communities often border non-Indigenous towns. These "border towns" are frequently sites of racial tension, discrimination, and violence. Indigenous women traveling to these towns for essential services or social interaction become targets, facing heightened risks of violence, abduction, and murder, often perpetrated by non-Indigenous individuals who operate with a sense of impunity.

-

Historical Trauma and Identity Disruption: The forced removal from ancestral lands, the breaking of treaties, and the residential school system (which systematically separated children from their families and culture) inflicted deep, intergenerational trauma. This trauma manifests in various ways, including substance abuse, mental health challenges, and the breakdown of community support systems, making individuals more vulnerable to violence. The loss of land is not merely an economic or political event; it is a spiritual wound that impacts identity, self-worth, and the fabric of Indigenous societies. When people are disconnected from their sacred places and traditional ways of life, the protective factors that once existed within their communities are weakened.

Maps as Tools of Resistance and Reclamation

Despite centuries of erasure, Indigenous peoples have never stopped mapping their world. Today, maps are powerful tools in the fight for justice and sovereignty, particularly in the MMIW movement.

-

Indigenous-Led Cartography: Contemporary Indigenous communities are actively engaged in mapping their ancestral territories, documenting traditional ecological knowledge (TEK), and asserting their inherent rights. These maps serve multiple purposes: they educate younger generations, inform land claims, guide environmental stewardship, and challenge the colonial narratives that sought to diminish Indigenous presence. They are acts of cultural survival and self-determination.

-

MMIW Mapping Projects: Advocates and organizations are creating interactive MMIW maps that visualize the scope of the crisis. These maps plot the locations where women have gone missing or been murdered, revealing patterns, identifying hotspots, and highlighting the systemic nature of the problem. They serve as a stark visual indictment of governmental inaction and societal indifference. By mapping these tragedies, advocates transform abstract statistics into a powerful, undeniable reality, giving a face and a place to each missing sister.

-

Connecting the Dots: These two types of maps—ancestral land maps and MMIW incident maps—are deeply intertwined. Overlaying them demonstrates how the MMIW crisis is not random but spatially concentrated in areas historically impacted by colonial policies: near reservations, along resource extraction corridors, and in regions where Indigenous land has been systematically exploited. This cartographic juxtaposition powerfully illustrates how the devaluation of Indigenous land often precedes and enables the devaluation of Indigenous lives.

Historical Trauma, Identity, and Resilience

The MMIW crisis, viewed through the lens of Indigenous land maps, is a profound statement about identity. For Indigenous peoples, land is not just property; it is a relative, a teacher, a source of spiritual strength, and the very foundation of their identity. To be removed from the land is to be severed from a vital part of oneself and one’s cultural heritage. The violence against Indigenous women is, therefore, an attack not just on individuals, but on the collective identity, sovereignty, and future of Indigenous nations.

Yet, amidst this profound trauma, there is immense resilience. Indigenous women are at the forefront of movements to reclaim land, protect water, and advocate for their communities. They are revitalizing languages, passing on traditional knowledge, and leading efforts to bring their missing sisters home and achieve justice for the murdered. The act of mapping, whether it’s charting ancestral hunting grounds or documenting MMIW cases, is an act of reclaiming narrative, asserting presence, and demanding accountability. It is a powerful affirmation that Indigenous peoples are still here, their cultures vibrant, and their fight for justice unwavering.

For the Conscious Traveler and History Enthusiast

Understanding the intricate relationship between Indigenous land maps and the MMIW crisis is crucial for anyone seeking a deeper, more ethical engagement with history and travel.

-

Acknowledge the Land: When you travel, learn whose traditional territory you are on. A land acknowledgment is not just a performative gesture; it is an act of recognizing Indigenous sovereignty and challenging the colonial narrative of "empty" land. Research the history of the local Indigenous nations, their treaties, and their contemporary presence.

-

Support Indigenous Businesses and Initiatives: Seek out and support Indigenous-owned businesses, artists, and cultural centers. Your dollars can directly contribute to economic self-determination and cultural revitalization within communities that have been historically dispossessed.

-

Learn and Listen: Engage with Indigenous perspectives and histories beyond what is taught in mainstream narratives. Read books by Indigenous authors, follow Indigenous news sources, and attend cultural events (when invited and appropriate). Listen to the voices of survivors, activists, and elders.

-

Advocate for Justice: Become informed about the MMIW crisis and support organizations working to address it. This could involve contacting elected officials, sharing information on social media, or donating to MMIW advocacy groups. Understand that true "historical education" means grappling with ongoing injustices.

-

Challenge Your Assumptions: Travel can be a transformative experience, but it requires an open mind and a willingness to confront uncomfortable truths. Recognize that the beautiful landscapes you visit have complex and often painful histories, and that the "untouched wilderness" was, and often still is, Indigenous land.

Conclusion

The Map of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, when superimposed on the ancient and enduring maps of Indigenous nations, tells a story far older and more profound than recent headlines suggest. It speaks to the enduring impacts of colonialism, the systemic vulnerabilities it created, and the profound connection between land, identity, and safety for Indigenous peoples. For the travel and history enthusiast, this understanding transforms a mere journey into a powerful opportunity for education, empathy, and advocacy. By acknowledging the true history of the land and supporting Indigenous-led efforts, we can contribute to a future where all Indigenous women, girls, and Two-Spirit people are safe, respected, and visible, their stories and sovereignty woven back into the living map of this continent.