Journey Through Uncharted Histories: A Review of The Great Lakes Indigenous Cartography Institute

Forget everything you thought you knew about maps. Forget the neat grid lines, the compass roses, the carefully delineated national borders. To truly understand the Great Lakes region – its history, its land, and its original peoples – one must shed the colonial lens and embrace a profoundly different cartographic philosophy. This is precisely the mission and unparalleled offering of The Great Lakes Indigenous Cartography Institute (GLICI), a groundbreaking cultural and research center that I recently had the privilege to immerse myself in. This isn’t just a museum; it’s a portal to a pre-contact world, a living archive of knowledge etched not on paper, but in memory, story, song, and the very landscape itself.

GLICI is situated on the shores of Lake Michigan, a deliberate choice that roots its mission in the ancestral lands of the Anishinaabeg and other Great Lakes nations. From the moment you step inside, the conventional notion of a "map" is challenged. The vast, open atrium features a stunning, illuminated relief map of the Great Lakes basin, but it’s not simply topographical. Projected onto its surface are dynamic overlays: migration routes of various nations, seasonal hunting and gathering territories, ancient trade networks, and the locations of sacred sites, all animated and narrated by Indigenous voices. This immediate sensory immersion sets the stage for an experience that is both intellectually rigorous and deeply spiritual.

The Institute’s core premise is that pre-contact Indigenous maps were not static representations of geography, but dynamic, multi-layered repositories of knowledge essential for survival, governance, and spiritual well-being. These "maps" existed in forms far more sophisticated and integrated than anything European cartographers could conceive before contact. They were oral histories, mnemonic devices, petroglyphs, wampum belts, astronomical observations, and an intimate, experiential knowledge of the land itself. GLICI masterfully curates exhibits that bring these diverse forms to life.

One of the most compelling sections is dedicated to Oral Cartography. Here, interactive displays allow visitors to listen to elders recounting ancestral journeys, describing seasonal camps, identifying medicinal plants by their location, and detailing the precise contours of rivers and portages through narrative. These are not just stories; they are GPS systems of the past, encoded with vital information about resources, hazards, and social territories. You can don headphones and hear an Ojibwe elder describe a canoe route across Lake Superior, not with cardinal directions, but with references to specific rock formations, the sound of certain rapids, the scent of particular cedar groves, and the constellation visible at dusk. The precision is astonishing, revealing a level of environmental literacy that modern society has largely lost.

Adjacent to this is a powerful exhibit on Wampum Belts as Cartographic Records. Often misunderstood as mere decorative items or currency, wampum belts were intricate historical documents, treaties, and indeed, maps. GLICI displays exquisite reproductions and explains how the arrangement of different colored beads, their patterns, and the "reading" of the belts by trained keepers conveyed not only diplomatic agreements but also the spatial relationships of allied nations, shared hunting grounds, and agreed-upon boundaries. A particularly poignant display shows how a wampum belt could delineate a river system or a series of villages, serving as a mnemonic map for envoys traveling between communities. The Institute’s researchers have done extensive work correlating these wampum records with historical accounts and archaeological findings, offering compelling evidence of their cartographic function.

The Institute also delves into the Landscape as a Living Map. This section features stunning photography and 3D models of significant Great Lakes landmarks – Spirit Island in Lake Superior, the Sleeping Giant formation, various effigy mounds – explaining how these natural features served as fixed points of reference, guiding markers, and sacred sites within the Indigenous worldview. Pre-contact peoples understood the land not as an empty space to be filled, but as a sentient being, rich with meaning and history. The contours of a hill, the bend of a river, the growth of a particular forest were all elements of a grand, interconnected map, guiding movement and informing resource management. GLICI highlights how these "natural maps" dictated seasonal migration patterns, ensured sustainable harvesting, and reinforced spiritual connections to specific territories.

Beyond the purely geographical, GLICI explores Celestial and Spiritual Cartography. Indigenous peoples of the Great Lakes observed the stars with profound accuracy, using constellations for navigation, timekeeping, and calendrical purposes. The exhibit showcases how the position of the sun, moon, and stars throughout the year informed planting and harvesting cycles, guiding communities through their annual rounds. Furthermore, the spiritual landscape – the locations of spirit helpers, sacred springs, and ceremonial sites – was an integral part of their spatial understanding. These were not abstract beliefs but tangible points of reference that influenced travel, settlement, and daily life. The Institute uses immersive dome projections to recreate the night sky as it would have appeared thousands of years ago, with Indigenous constellations highlighted, accompanied by traditional star stories.

What makes GLICI more than just a passive viewing experience is its commitment to interactive learning and community engagement. Throughout the Institute, touchscreens allow visitors to delve deeper into specific topics, view historical documents (both Indigenous and colonial), and listen to contemporary Indigenous scholars and knowledge keepers discuss the enduring relevance of these ancient cartographies. There are regular workshops on traditional navigation techniques, storytelling, and language revitalization, connecting visitors directly with the living traditions that kept these maps alive for millennia. The gift shop, far from being a collection of tourist trinkets, offers books by Indigenous authors, traditional crafts, and ethically sourced goods from Great Lakes Native communities, further supporting their cultural continuity.

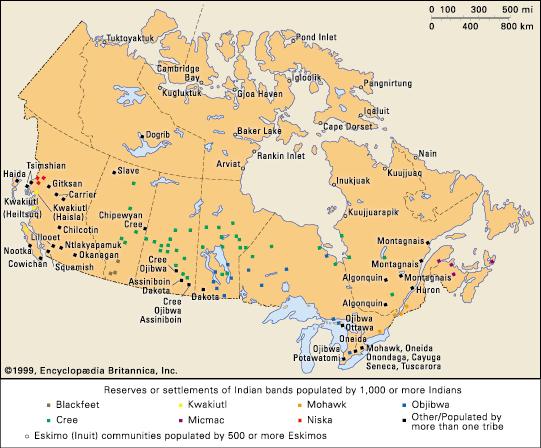

The profound impact of European contact on Indigenous cartography is also handled with sensitivity and scholarly depth. The Institute doesn’t shy away from discussing the subsequent erasure and marginalization of Indigenous knowledge systems. Early European maps of the Great Lakes, while often reliant on Indigenous guides and their knowledge, rarely credited them and frequently superimposed European concepts of ownership and boundaries over existing Indigenous territories. GLICI presents a fascinating comparison of early European maps alongside reconstructions of Indigenous spatial knowledge, illustrating the stark differences in worldview and the tragic consequences of colonial mapping for Indigenous land rights and sovereignty. This section is a crucial reminder that maps are not neutral; they are powerful tools that reflect and shape political realities.

Visiting GLICI is a transformative experience for anyone interested in history, geography, or Indigenous cultures. It fundamentally alters one’s perception of "maps" and "mapping," revealing a richness and complexity that Western cartography has only begun to appreciate. It underscores the incredible resilience of Great Lakes Native peoples, who, despite centuries of attempted cultural annihilation, have maintained and revitalized their ancestral knowledge. The Institute is not just preserving the past; it is actively shaping a more informed and respectful future.

The Great Lakes Indigenous Cartography Institute is more than a recommended travel destination; it’s an essential pilgrimage. It offers an unparalleled opportunity to engage with a sophisticated and profound understanding of the land, one that existed long before the arrival of Europeans and continues to resonate today. By shedding preconceived notions and opening oneself to these ancient "maps," visitors gain not only a deeper appreciation for the Great Lakes region but also a critical new perspective on knowledge, territory, and the enduring power of Indigenous wisdom. This institution is a beacon of decolonization, guiding us toward a more holistic and respectful understanding of the world we inhabit. It’s an experience that will stay with you long after you’ve left its hallowed halls, forever changing how you look at a map, and more importantly, how you look at the land beneath your feet.