Unearthing the Heart of Ancient America: A Journey Through the Hopewell Culture Distribution Map

Imagine a vast network, stretching across the ancient heartland of North America, connecting diverse communities through shared beliefs, sophisticated artistry, and an astonishing trade system. This isn’t a modern highway map, but a distribution map of the Hopewell culture, a pre-Columbian civilization that flourished from roughly 200 BCE to 500 CE. For the discerning traveler and history enthusiast, this map is far more than just lines and shaded areas; it’s a living testament to a complex and innovative people, offering profound insights into their history, identity, and enduring legacy.

This article delves directly into the essence of the Hopewell distribution map, decoding its implications for understanding one of North America’s most enigmatic and influential ancient cultures. Forget the notion of a single empire; the Hopewell story is one of shared ideas, monumental landscapes, and an interconnected world that predates European arrival by over a millennium.

Decoding the Geographic Footprint: Where the Hopewell Thrived

The first glance at a Hopewell culture distribution map immediately reveals a compelling geographic truth: this was a civilization deeply intertwined with the great river systems of the Eastern Woodlands. The core area, the epicenter of Hopewell influence, is prominently centered in the Ohio River Valley, particularly in what is now Ohio and Illinois. Here, the density of archaeological sites, especially monumental earthworks, is staggering.

However, the map’s shading extends far beyond this core, reaching into parts of Indiana, Kentucky, Michigan, Wisconsin, Iowa, Missouri, Arkansas, and even pockets of the Appalachian region and the Southeast. This expansive, yet often diffuse, spread is key to understanding the Hopewell phenomenon. It wasn’t a unified political entity with defined borders like the Roman Empire. Instead, the map illustrates the reach of the Hopewell Interaction Sphere – a concept crucial for grasping their identity.

The map shows clusters of activity along major tributaries of the Mississippi River, such as the Illinois River, the Scioto River, and the Muskingum River. These waterways were not barriers but vital arteries, facilitating travel, communication, and the movement of goods and ideas. The choice of these fertile river valleys provided access to abundant resources: diverse flora and fauna, rich soils for horticulture, and clay for pottery. This strategic placement was foundational to their cultural flourishing and the extensive networks they would establish.

The Hopewell Interaction Sphere: A Shared Identity Forged in Trade

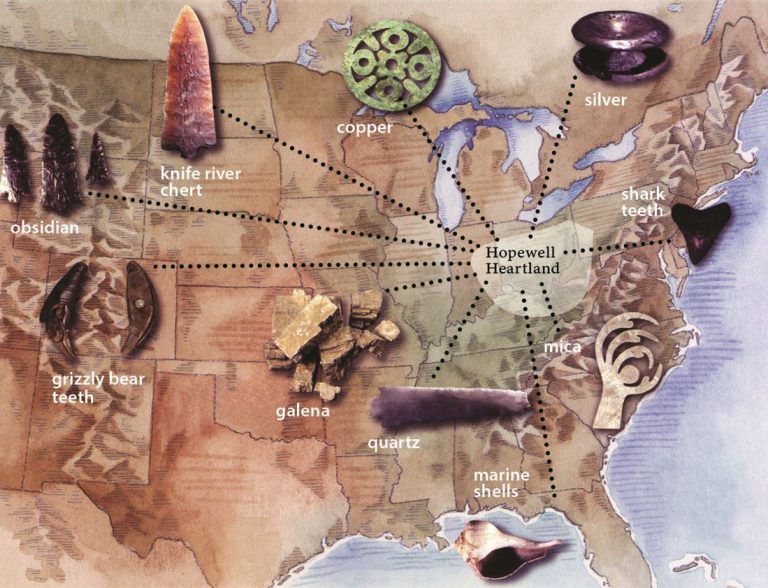

Perhaps the most fascinating aspect illuminated by the distribution map is the sheer scale and sophistication of the Hopewell Interaction Sphere. This wasn’t just about local communities; it was a vast, pan-regional exchange network that shaped a shared cultural identity across hundreds of thousands of square miles. The map, in essence, is a visual representation of their trade routes and the cultural diffusion that resulted.

Imagine tracing lines from the Ohio core to distant points on the map:

- Copper from the Lake Superior region (present-day Michigan and Wisconsin) traveled south, transformed into intricate ornaments, tools, and ceremonial objects found in Hopewell burials.

- Obsidian, a volcanic glass used for razor-sharp tools and ceremonial blades, journeyed thousands of miles from sources as far west as the Yellowstone region (Wyoming and Idaho).

- Mica, a shimmering mineral, came from the Appalachian Mountains (North Carolina, Tennessee), fashioned into cutouts depicting hands, raptors, and abstract shapes.

- Marine shells (conch, whelk) and pearls were sourced from the Gulf of Mexico and the Atlantic Coast, indicating trade routes extending over 1,000 miles.

- Galena (lead ore) from Missouri, pipestone (catlinite) from Minnesota, and various types of chert and flint for tool-making were also widely exchanged.

What does this tell us about Hopewell identity? It suggests a shared aesthetic, a common set of values, and a network of elite individuals or groups who participated in these exchanges. The goods themselves were often more symbolic than purely utilitarian. They conferred status, were used in elaborate burial rituals, and served as tangible expressions of shared spiritual beliefs and social structures. The act of acquiring and displaying these exotic materials created a powerful, unifying identity among those who participated in the Sphere, distinguishing them from purely local groups.

This wasn’t a centralized empire dictating terms, but a flexible, decentralized system where communities adopted similar ceremonial practices, artistic styles, and shared symbols. The map shows us where these shared ideas took root and flourished, creating a cultural tapestry woven with threads from distant lands.

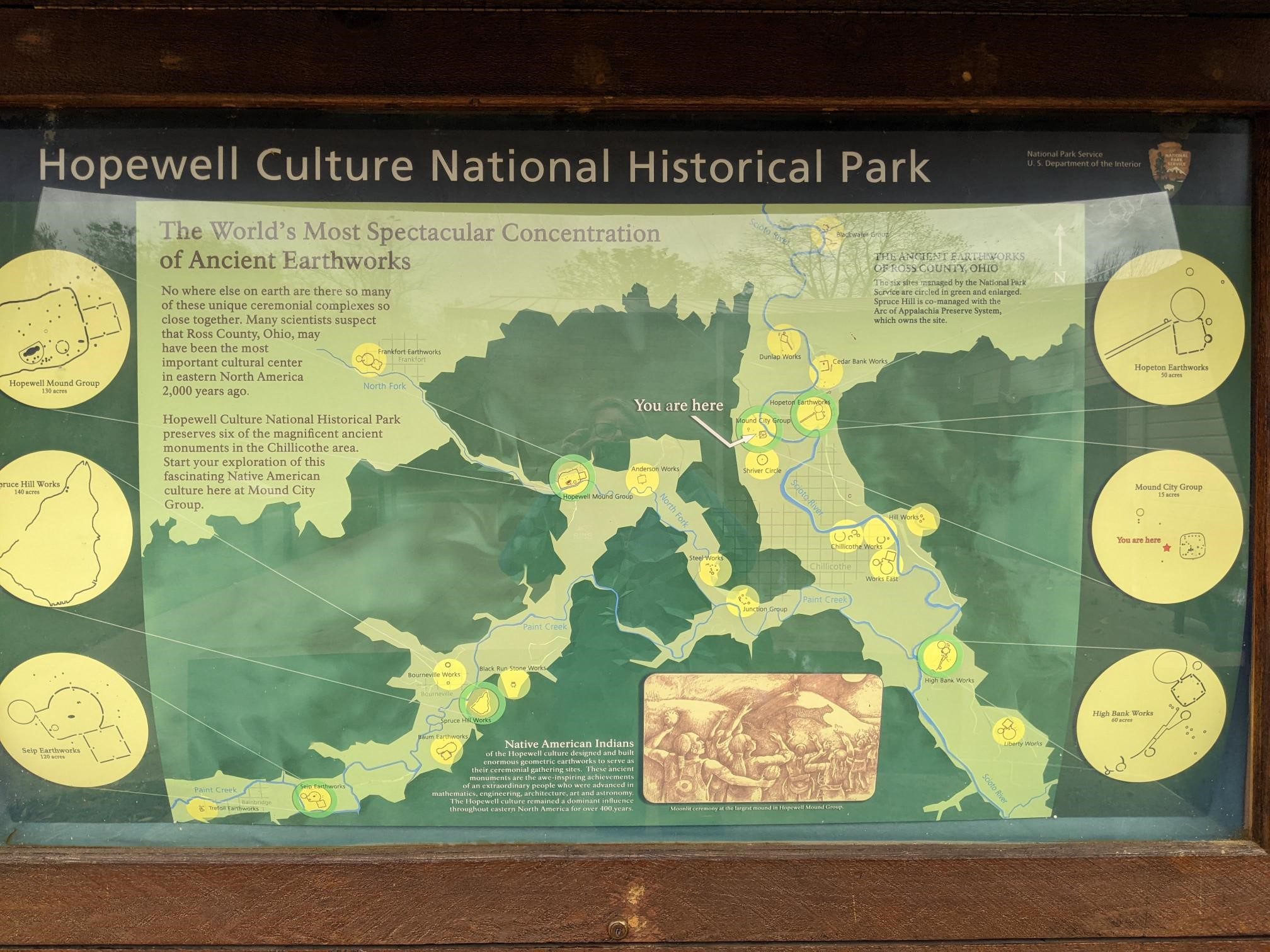

Monumental Landscapes: Earthworks as Expressions of Belief and Power

No discussion of the Hopewell culture is complete without acknowledging their monumental earthworks, and the distribution map highlights the key areas where these impressive structures are concentrated. The Ohio River Valley, particularly sites like Newark Earthworks, Fort Ancient, and Mound City, stands out as a nexus of this architectural prowess.

These earthworks were not mere piles of dirt. They were precisely engineered structures, often aligned with celestial events, demonstrating sophisticated understanding of astronomy and geometry. The map shows us where these centers of ritual and community were established:

- Geometric Earthworks: Massive circles, squares, octagons, and other complex shapes, often enclosing dozens or even hundreds of acres. The Newark Earthworks, for example, features a perfect octagon connected to a large circle by parallel walls, spanning over four square miles. Their purpose remains debated but likely involved ceremonial gatherings, astronomical observatories, and perhaps even defensive elements. They required immense labor and social coordination, speaking volumes about the collective identity and organization of Hopewell communities.

- Burial Mounds: Conical and loaf-shaped mounds, often containing elaborate burials with a wealth of grave goods sourced from across the Interaction Sphere. These mounds served as markers of ancestry, sacred spaces, and perhaps as a way to connect the living with the spiritual realm. The presence of exotic trade goods in these burials underscores the importance of the Interaction Sphere in defining status and identity even in death.

- Effigy Mounds: While less common in the Hopewell core than in later cultures, some early effigy mounds (e.g., Serpent Mound in Ohio) are sometimes associated with the broader Hopewell period, adding another layer to their diverse architectural expressions.

The distribution of these earthworks on the map isn’t random. It signifies areas of concentrated population, shared ceremonial practices, and a collective investment in creating sacred landscapes. These sites served as focal points for their shared identity, places where communities came together to perform rituals, honor ancestors, and reinforce their cultural ties.

Daily Life Beyond the Grandeur: Sustaining a Sophisticated Culture

While the earthworks and exotic trade goods paint a picture of grandeur, the distribution map also implicitly speaks to the daily lives of the Hopewell people. The concentration of sites along fertile river valleys indicates a mixed subsistence strategy. They were not exclusively agriculturalists like later Mississippian cultures, but rather skilled horticulturists, cultivating native plants like squash, gourds, sunflowers, maygrass, and goosefoot. This was supplemented by extensive foraging, hunting (deer, turkey, small game), and fishing.

Their settlements were typically villages or hamlets, often located near the ceremonial centers but rarely directly within the earthworks themselves. The map shows us where these population centers were viable, supported by a rich and diverse natural environment. Their homes were likely pole-and-thatch structures, designed for comfort in the seasonal climates of the Eastern Woodlands.

The pottery found across the Hopewell distribution, though varying regionally, often shares decorative elements like rocker stamping and zoned decoration, further cementing the idea of a shared material culture that transcended local variations. This commonality in everyday objects, alongside the exotic ritual items, speaks to a deeply ingrained cultural identity.

The Enigma of Decline and Transformation

Around 400-500 CE, the Hopewell Interaction Sphere began to wane. The grand ceremonial earthworks ceased to be built, the elaborate trade networks dissolved, and the distinctive Hopewell artifacts became less common. The distribution map, in its temporal understanding, shows this fading. It’s not a sudden disappearance but a transformation.

The reasons for this decline are complex and multifaceted. Scholars propose various factors:

- Climate Change: A shift to cooler, drier conditions may have impacted crop yields and resource availability.

- Resource Stress: Intensive use of local resources might have led to depletion.

- Social and Political Shifts: The highly centralized nature of the ceremonial cults or elite groups might have become unsustainable, leading to fragmentation.

- Rise of New Cultural Expressions: Regional cultures continued to evolve, perhaps adopting new forms of social organization or religious practices that superseded the Hopewell model.

Crucially, the people didn’t vanish. They adapted, evolved, and their descendants are the ancestors of many modern Native American tribes in the region, including the Shawnee, Miami, Potawatomi, and others. The Hopewell map, therefore, also marks a significant turning point in the trajectory of ancient North American history, a precursor to the Mississippian cultures that would follow.

Legacy and the Modern Traveler

For the modern traveler and history enthusiast, the Hopewell culture distribution map is an invitation to explore. It points to UNESCO World Heritage sites like the Newark Earthworks and Mound City Group (part of the Hopewell Culture National Historical Park) in Ohio, where the scale and precision of their ancient achievements can still be experienced. Visiting these sites allows one to walk in the footsteps of these ancient peoples, to stand within the geometric enclosures and ponder the cosmic alignments that guided their builders.

The map encourages us to look beyond the surface, to understand that North America has a deep, rich history of complex civilizations, far predating European contact. The Hopewell, with their intricate trade networks, monumental architecture, and sophisticated artistry, offer a powerful counter-narrative to simplistic views of pre-Columbian societies.

Their story, as told by the distribution map, is one of ingenuity, shared identity, and an astonishing ability to connect disparate communities over vast distances. It reminds us that "identity" isn’t always defined by political borders but can be forged through shared beliefs, ritual practices, and the exchange of valued goods and ideas. The Hopewell culture, though long past, continues to speak to us through the landscapes they shaped and the artifacts they left behind, inviting us to delve deeper into the heart of ancient America.