Forget the sterile grid lines of Google Maps. Forget the dispassionate cartography of modern atlases. To truly understand the Great Lakes, to grasp the profound connection between land, water, and human experience, you must journey to a different kind of map – one etched in memory, woven into story, carved into rock, or meticulously drawn on birch bark. These are the Great Lakes Native American maps, sophisticated systems of knowledge that predate European arrival by millennia. And there’s no better place to begin unearthing this rich legacy than the Field Museum in Chicago.

This isn’t just a museum visit; it’s a recalibration of your geographical imagination. The Field Museum, strategically positioned within the vast watershed of the Great Lakes, serves as an unparalleled gateway to understanding Indigenous cartography not as a quaint historical curiosity, but as a living, breathing testament to complex environmental knowledge, spiritual wisdom, and enduring cultural resilience.

The Field Museum: A Cartographic Crossroads

The Field Museum is a titan among natural history institutions, but its true strength, when it comes to understanding Native American maps, lies not in a single dedicated exhibit (though that would be magnificent), but in the comprehensive and thoughtfully curated "Native North America Hall" and its broader commitment to Indigenous voices and perspectives. Here, the concept of "map" expands beyond a two-dimensional representation to encompass tools, trade routes, ceremonial objects, and oral histories that collectively chart a deeply relational geography.

As you step into the hall, you’re not just looking at artifacts; you’re deciphering fragments of ancient maps. Consider the intricately decorated pottery, the finely crafted tools, the woven baskets – each speaks of resource locations, travel routes, and specialized knowledge of the land’s bounty. The trade networks, meticulously displayed, are themselves a kind of map, illustrating the pathways of exchange that connected disparate communities across the Great Lakes basin, from the copper mines of Lake Superior to the fertile agricultural lands south of Lake Michigan.

What makes the Field Museum experience so powerful is the context it provides. Unlike merely reading about Indigenous maps, seeing the physical manifestations of the cultures that produced them helps you visualize the landscape through their eyes. You begin to understand that a map wasn’t just about where things were, but how they were connected, who lived there, and the stories that made a place sacred or significant.

Beyond Western Grids: The Nature of Indigenous Mapping

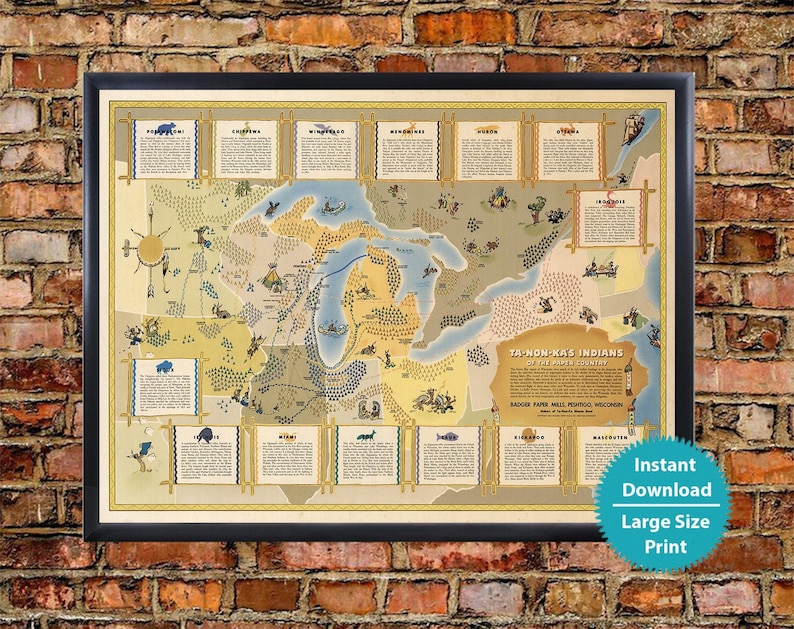

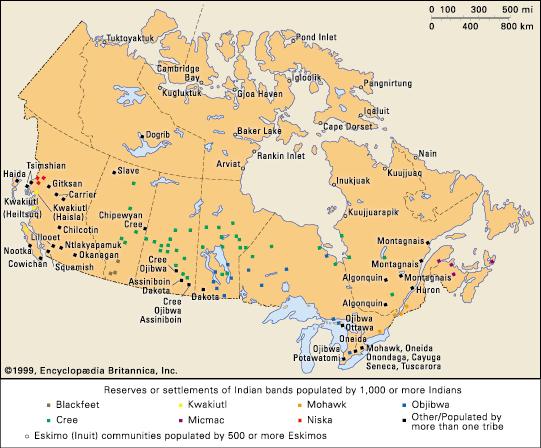

To appreciate what you’re seeing at the Field Museum, it’s crucial to shed Western preconceptions of cartography. For European navigators, maps were primarily tools for claiming territory, marking boundaries, and facilitating resource extraction. For the Anishinaabeg (Ojibwe, Odawa, Potawatomi), Ho-Chunk (Winnebago), Menominee, Miami, and countless other nations of the Great Lakes, maps served a far more intricate and holistic purpose.

-

Memory & Oral Tradition: Many Indigenous maps were not drawn on a physical surface but existed in the collective memory, passed down through generations via storytelling, song, and ceremony. These "maps" contained not just routes and landmarks, but also historical events, spiritual narratives, and ecological information crucial for survival. A journey, for example, might be remembered not as a series of compass bearings, but as a sequence of stories tied to specific features: "where the old woman wept for her lost child," "the place where the blueberries grow thickest after the first frost," "the rapids where the thunder beings reside." The museum’s exhibits, particularly those featuring audio recordings of Indigenous languages and stories, offer glimpses into this rich oral tradition.

-

Multisensory Experience: Indigenous maps engaged all senses. A "map" might include the smell of certain plants indicating a medicinal gathering spot, the sound of a particular waterfall marking a portage, or the feel of a specific type of rock underfoot. The Field Museum, while limited to visual and auditory displays, endeavors to evoke this multisensory engagement through detailed dioramas and immersive cultural presentations. You can almost hear the lapping waves of Lake Michigan, smell the pine forests, or feel the chill of a winter journey as you explore the exhibits.

-

Dynamic & Relational: Unlike static Western maps, Indigenous maps were dynamic, constantly updated with new information about changing seasons, resource availability, or community movements. They were relational, emphasizing the interconnectedness of all elements within the landscape – humans, animals, plants, and spirits. A map of a hunting ground wasn’t just lines on a surface; it was a guide to the deer’s migration patterns, the bear’s hibernation dens, and the sacred protocols for a respectful harvest. The museum’s depiction of seasonal cycles and resource management techniques across different Great Lakes nations beautifully illustrates this dynamic and relational worldview.

-

Materials & Mediums: While birch bark maps are perhaps the most famous physical examples, Indigenous cartography manifested in diverse forms:

- Birch Bark: The Ojibwe, particularly, were masters of drawing intricate maps on rolls of birch bark, often depicting waterways, portages, villages, and significant landmarks. These were practical tools for navigation and trade. While the Field Museum may not always have these specific artifacts on display due to their fragility, its extensive collection of birch bark containers and crafts demonstrates the material mastery that made such mapping possible.

- Hide: Animal hides, durable and portable, were also used for mapping, sometimes depicting hunting territories or migration routes.

- Wampum Belts: These intricate belts of shell beads, primarily used by nations like the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) but traded and understood across the Great Lakes, served as mnemonic devices for treaties, historical events, and territorial agreements – functioning as a form of diplomatic and historical mapping.

- Rock Art & Petroglyphs: Throughout the Great Lakes, ancient rock carvings depict celestial events, spirit beings, and possibly routes or significant places, serving as enduring markers on the landscape itself.

- Ceremonial Objects & Art: Many cultural items, from pipe stems to clothing, incorporated designs that referenced specific landscapes, sacred sites, or ancestral journeys, imbuing them with a cartographic function.

Deciphering the Field Museum’s Indigenous Maps

As you traverse the "Native North America Hall," approach each exhibit with a cartographer’s eye, but one trained in Indigenous knowledge.

- The Ojibwe Birch Bark Canoe: This iconic watercraft, central to Great Lakes travel, isn’t just a mode of transport; it’s a cartographic tool. Its design reflects deep knowledge of waterways, currents, and portage routes. The exhibits detailing its construction and use implicitly map the vast network of rivers and lakes that formed the arteries of Indigenous life.

- Tools for Gathering and Hunting: Displays of fishing spears, wild rice processing tools, and hunting implements speak volumes about resource distribution and seasonal movements – a practical, functional map of the Great Lakes ecosystem and its bounty.

- Trade Route Narratives: Look for exhibits that highlight the vast trading networks that crisscrossed the region. The flow of copper, shells, furs, and agricultural products sketches out ancient highways and waterways, demonstrating a sophisticated understanding of regional geography and economic connections.

- Cultural Expressions of Place: Pay close attention to the art, regalia, and ceremonial objects. Often, the patterns, colors, and imagery tell stories of specific landscapes, ancestral territories, or cosmological journeys – maps of the spirit world interwoven with the physical. The floral patterns in Anishinaabe beadwork, for instance, are not just decorative; they are often deeply connected to the plant life of their homelands.

- The Power of Language: The museum’s efforts to incorporate Indigenous languages are vital. Each word for a place, a plant, or an animal carries layers of meaning, history, and ecological insight – a linguistic map of the environment.

Beyond the Glass Cases: The Living Legacy

The Field Museum doesn’t just present historical artifacts; it connects them to the vibrant, living cultures of today’s Great Lakes Native American nations. This connection is crucial, as Indigenous cartography isn’t a dead art. Contemporary Indigenous artists, storytellers, and land stewards continue to draw upon these ancient mapping principles, advocating for environmental protection, asserting land rights, and revitalizing cultural knowledge.

Visiting the Field Museum helps you understand the profound implications of this legacy:

- Environmental Stewardship: Indigenous maps prioritize a sustainable relationship with the land, emphasizing cyclical patterns, resource regeneration, and the interconnectedness of all life. This perspective offers invaluable lessons for addressing modern environmental challenges in the Great Lakes basin.

- Understanding Land Claims: To comprehend current land claims and treaty rights, one must first grasp the historical Indigenous understanding of territory, not as lines on a colonial map, but as homelands defined by cultural practices, spiritual connections, and ancestral presence.

- Decolonizing Perspectives: By engaging with Indigenous cartography, you challenge the dominant, often colonial, narratives of geography. You learn to see the Great Lakes not as a blank slate awaiting European discovery, but as a deeply mapped and understood landscape with a rich, complex human history stretching back thousands of years.

Your Journey to a Deeper Great Lakes Understanding

So, as you plan your next trip to the Great Lakes, make a deliberate detour to Chicago’s Field Museum. Don’t just walk through the "Native North America Hall"; engage with it. Look for the maps hidden in plain sight – in the tools, the trade routes, the ceremonial objects, the very stories that imbue these artifacts with meaning.

- Before You Go: Check the Field Museum’s website for current exhibitions, as they frequently update and rotate displays. Consider researching specific Great Lakes nations (Ojibwe, Potawatomi, Menominee, Ho-Chunk) to better appreciate the cultural context of the artifacts.

- While You’re There: Take your time. Read every interpretive panel. Listen to any audio guides. Allow yourself to imagine the landscapes and lifeways that these objects represent. Think about how these items functioned as part of a larger system of knowledge and navigation.

- After Your Visit: Carry this expanded understanding with you. When you gaze at Lake Michigan, or paddle a quiet river, or hike through a northern forest, try to see it through the lens of Indigenous cartography. Recognize the layers of history, the whispers of ancient pathways, and the enduring presence of nations who have mapped these lands and waters for millennia.

The Field Museum offers more than just a glimpse into the past; it provides a profound re-education in how we understand place. It reminds us that maps are not just about lines and labels, but about stories, relationships, and a deep, abiding connection to the living world. And in the heart of the Great Lakes region, this understanding is perhaps the most valuable map you can acquire.