Etched in Stone, Woven in Story: Decoding Native American Maps of Paleo-Indian America

Forget your GPS. Unlearn the grid of latitude and longitude. To truly understand the ancient landscapes of North America, to trace the very first footsteps of its human inhabitants, we must shed our modern cartographic biases and embrace a form of mapping far older, far richer, and deeply embedded in the land itself: Native American maps of Paleo-Indian sites. This isn’t about finding a parchment scroll marked "Paleo-Indian Hunting Ground." It’s about a profound journey into the living landscape, where stories are maps, rock art is a historical atlas, and sacred sites are navigational beacons passed down through millennia.

For the intrepid traveler seeking a connection to the deepest human history of this continent, exploring this concept isn’t just an archaeological tour; it’s a spiritual and intellectual expedition. We’re talking about the earliest peoples of the Americas, the Paleo-Indians, who arrived over 15,000 years ago, master navigators of an Ice Age world. While they left no conventional maps, their descendants—the myriad Indigenous nations of today—preserved, adapted, and expanded upon a sophisticated understanding of the land that undoubtedly traces its roots back to these first explorers.

Beyond the Cartographic Grid: What Are Native American "Maps"?

When we speak of Native American maps, we’re rarely talking about paper or parchment. Instead, these are dynamic, multi-layered systems of knowledge. They manifest as:

- Oral Traditions: Epic narratives, songs, and ceremonies that describe ancestral migrations, resource locations, territorial boundaries, and significant events tied to specific landscape features. A mountain isn’t just a peak; it’s a marker of a journey, a site of creation, or a place where a crucial historical event unfolded.

- Rock Art: Petroglyphs (carved into stone) and pictographs (painted on stone) are often more than just art. They can depict hunting routes, water sources, constellations, clan territories, or even the layout of sacred spaces. They are enduring visual records etched into the landscape itself.

- Sacred Geography: The arrangement of ceremonial sites, burial grounds, and places of power forms a spiritual and practical map. These sites often align with astronomical events or natural features, guiding movement and understanding of the cosmos and the earth.

- Physical Layouts: Earthworks, stone alignments, and even the strategic placement of settlements reflect a deep spatial awareness and practical knowledge of resources, defenses, and ceremonial purposes.

The critical link to Paleo-Indian sites lies in the continuity of human occupation and knowledge. While direct "maps" from 15,000 years ago are elusive, the systems of understanding, navigating, and communicating about the landscape were forged during that ancient era. Later Indigenous maps, whether carved or spoken, often incorporate knowledge of very old places, ancient migration routes, and enduring sacred geographies that predate recorded history.

Echoes of the First Americans: Navigating the Ice Age

Imagine the Paleo-Indians. They weren’t just wandering aimlessly. They were highly skilled hunters and gatherers, intimately familiar with vast territories. They tracked megafauna like mammoths and mastodons across continents, understood seasonal resource availability, and knew the safest routes through challenging terrain. This required an extraordinary internal, or "mental," map of their world.

Their "maps" would have been crucial for survival:

- Where are the perennial water sources in this arid land?

- Which passes are traversable in winter?

- Where do the caribou migrate?

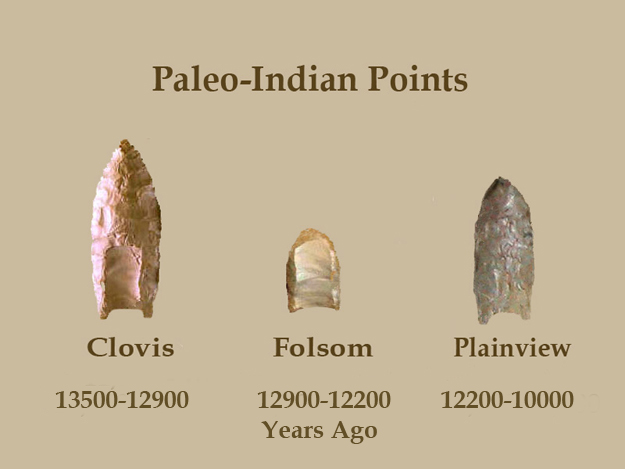

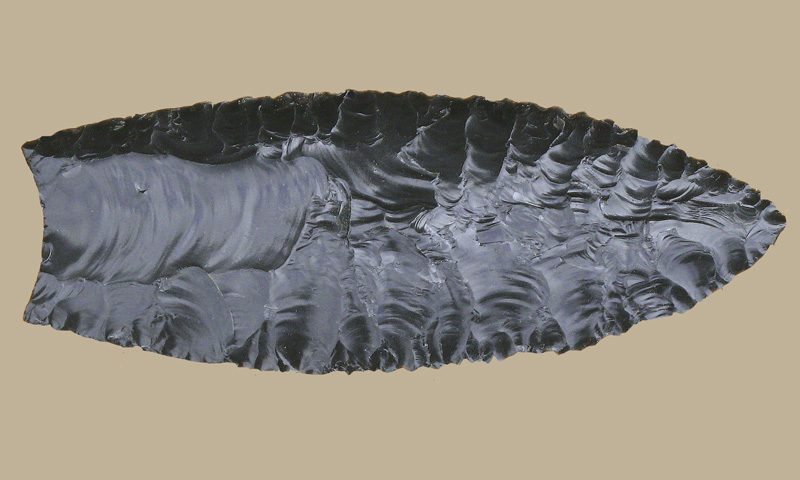

- Where can we find chert or obsidian for tools?

- Which caves offer shelter?

This inherited knowledge, passed down through generations, became the bedrock of the more formalized mapping traditions seen in later Indigenous cultures. When we visit a site today with ancient rock art depicting a herd of animals, or a landscape feature central to an origin story, we are, in a sense, tapping into the remnants of these Paleo-Indian mental maps.

The Southwest & Great Basin: A Living Archive of Deep Time

For travelers keen to experience this profound connection, the American Southwest and Great Basin regions offer an unparalleled opportunity. This vast expanse, characterized by dramatic canyons, towering mesas, and stark deserts, boasts some of the longest continuous human occupation in North America. Here, the landscape itself is a historical document, and Indigenous cultures have maintained an unbroken link to their ancestral lands for millennia, often preserving knowledge of sites inhabited by the earliest peoples.

Petroglyph National Monument, New Mexico:

Begin your journey here, just outside Albuquerque. This monument preserves one of the largest petroglyph sites in North America, with an estimated 25,000 images carved into volcanic rocks. While many carvings date to more recent Pueblo periods, some are thousands of years old, their creators lost to time. As you walk the trails, observe the symbols: spirals, human-like figures, animal tracks, geometric patterns. Are these simply art? Or are they mnemonic devices, marking important places, telling stories of hunts, migrations, or spiritual journeys across the landscape?

Imagine a Paleo-Indian hunter, thousands of years ago, leaving a mark to indicate a good hunting ground, a safe passage, or a significant event. The continuity of human mark-making on this land is palpable. These petroglyphs act as ancient signposts, components of a vast, open-air map that transcends generations. They remind us that communication and a deep understanding of place have been central to human existence here since time immemorial.

Nine Mile Canyon, Utah: The "World’s Longest Art Gallery"

Venture into the remote, breathtaking beauty of Nine Mile Canyon in Utah, often called the "world’s longest art gallery." Here, thousands of petroglyphs and pictographs adorn the canyon walls, left by various cultures over thousands of years, including the Fremont people and earlier inhabitants. Some panels are so ancient, their exact dating is a challenge, but their presence speaks to a continuous human presence stretching back to deeply ancient times.

As you drive or hike through the canyon, you’ll encounter complex panels that depict intricate scenes: large animal figures, enigmatic humanoids, hunting scenarios, and abstract designs. Some scholars interpret these not just as individual images but as components of larger narratives—story maps that chronicle seasonal movements, resource availability, or the spiritual topography of the region. A series of sheep figures might indicate a migration route; a human figure holding a spear might mark a prime hunting spot. These are not merely pictures; they are data points on an ancient map, critical for survival and cultural transmission. The sheer volume and age of the art here make it a powerful place to contemplate the enduring human impulse to map and record their world on the very fabric of the earth.

Chaco Culture National Historical Park, New Mexico:

While Chaco Canyon is renowned for its monumental Puebloan architecture (dating from 850 to 1250 CE), its significance for understanding Indigenous mapping traditions, and their deep roots, is profound. The Chacoan people constructed an elaborate system of "roads" and "outliers" extending for hundreds of miles across the landscape. These aren’t simply functional roads; they often lead to natural features, water sources, or other significant sites, creating a vast, interconnected network that functions as a highly sophisticated map of their world.

The precision with which these structures align with astronomical events (solstices, equinoxes) further demonstrates an advanced understanding of time, space, and the cosmos—a "cosmic map" that guided their lives. While Chaco’s peak is far removed from the Paleo-Indian era, the underlying principles of sacred geography, resource management, and communal navigation almost certainly evolved from millennia of earlier Indigenous habitation. Visiting Chaco is to walk upon a landscape that has been intricately mapped and understood by human beings for thousands of years.

Oral Traditions and Landscape Narratives: Maps Spoken Aloud

Beyond the visible rock art, the most profound "maps" are often those held in the memories and stories of Indigenous elders. Many Native American cultures possess rich oral traditions that function as encyclopedic guides to their ancestral lands. These narratives often describe:

- Place Names: Each peak, canyon, river, and spring has a name, and that name often carries a story, a warning, or a resource indicator. For example, a name might mean "place where the deer gather in autumn," or "canyon of the dangerous winds."

- Migration Routes: Ancient stories recount the journeys of ancestral clans, describing the sequence of significant landmarks, the challenges encountered, and the resources found along the way. These are verbal maps of incredible detail and accuracy.

- Resource Calendars: Narratives might tie the ripening of certain plants or the presence of certain animals to specific locations and times of year, providing a dynamic, seasonal map for sustenance.

While these stories are not always publicly shared, their existence underscores the depth of Indigenous knowledge about their homelands—knowledge that has been honed and passed down since the earliest days of human habitation. When visiting these lands, simply knowing that such a rich tapestry of stories exists enriches the experience, transforming a mere landscape into a vibrant, storied realm.

Visiting with Respect and Openness

For the traveler, engaging with Native American maps of Paleo-Indian sites is not about finding definitive "Paleo-Indian maps" in a Western sense. It’s about cultivating a deeper appreciation for the ingenuity, resilience, and profound connection to land that Indigenous peoples have demonstrated for thousands of years.

Practical Advice for Your Journey:

- Educate Yourself: Before you go, research the specific Indigenous nations whose ancestral lands you will be visiting. Understand their history, culture, and their ongoing relationship with the land.

- Visit Designated Sites: Focus on established archaeological parks and monuments where interpretation is provided by experts and where cultural sensitivity is paramount.

- Respect the Land: Stay on marked trails, do not touch rock art, and leave no trace. These sites are sacred and irreplaceable.

- Seek Indigenous Voices: If opportunities arise to hear from Indigenous guides or educators, embrace them. Their perspective offers an invaluable, living connection to the past.

- Look Beyond the Obvious: Train your eye to see the landscape as a dynamic, interconnected system. Consider how ancient peoples would have read the subtle signs of water, game, and shelter.

- Embrace the "Why": Instead of asking "Where is the map?", ask "How did these people understand and navigate their world? How did they pass that knowledge on?"

Conclusion: The Land Remembers

Exploring Native American maps of Paleo-Indian sites is an invitation to journey into a different way of knowing. It’s a recognition that long before satellites and GIS, human beings possessed sophisticated, nuanced methods of mapping their world—methods born of necessity, refined by generations, and deeply interwoven with their spiritual and cultural identities.

From the ancient petroglyphs of Nine Mile Canyon to the vast cosmic alignments of Chaco, the echoes of Paleo-Indian footsteps resonate through these landscapes. They speak of a time when the entire world was a map, etched in stone, woven in story, and remembered in the very contours of the earth. As a traveler, to engage with this profound legacy is to not only explore ancient sites but to open your mind to an ancient wisdom, gaining an unparalleled understanding of North America’s deepest human history. It’s a journey that re-maps your own understanding of place, time, and the enduring human spirit.