Echoes in the Peaks: Navigating Glacier National Park Through Native American Maps

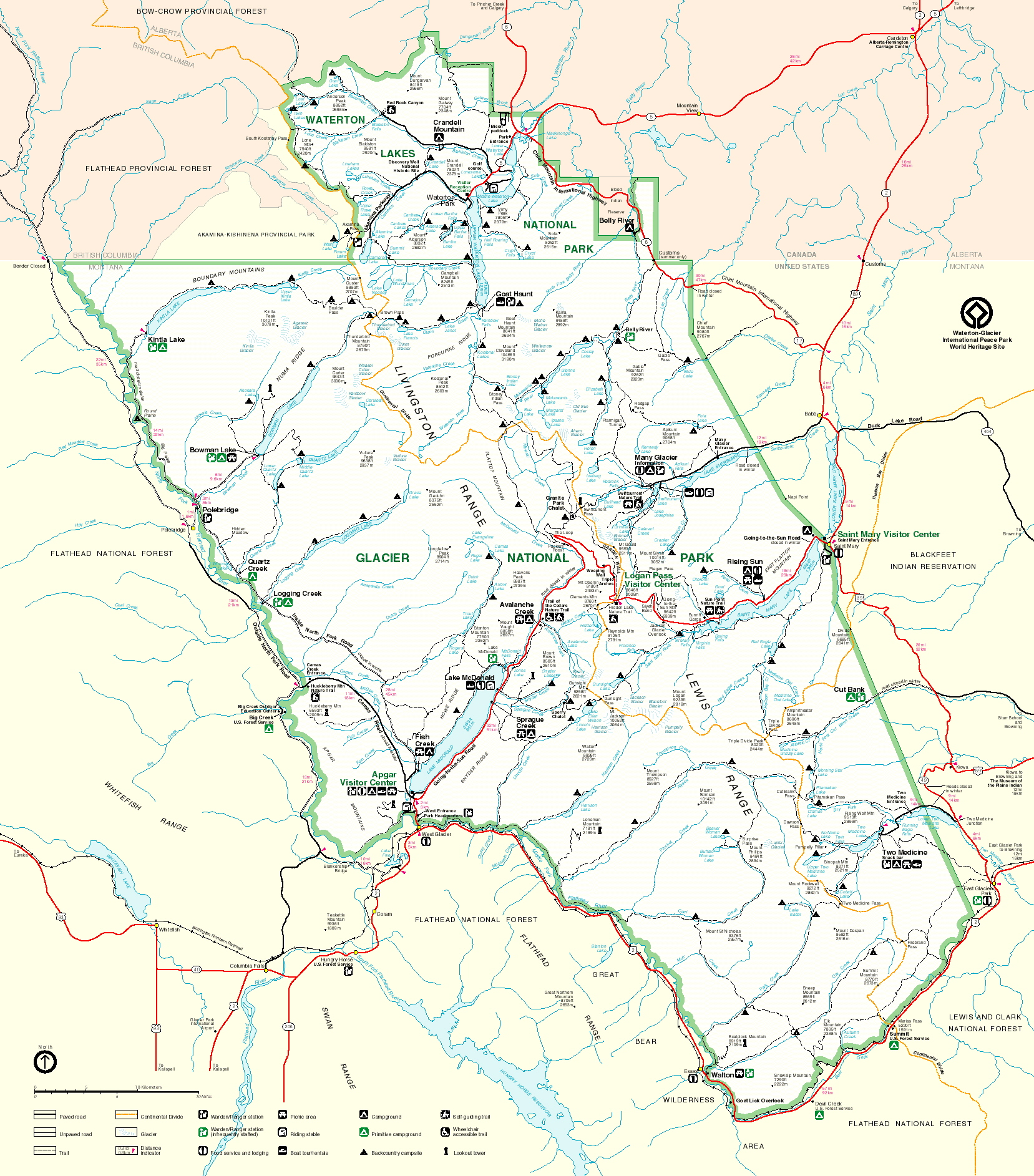

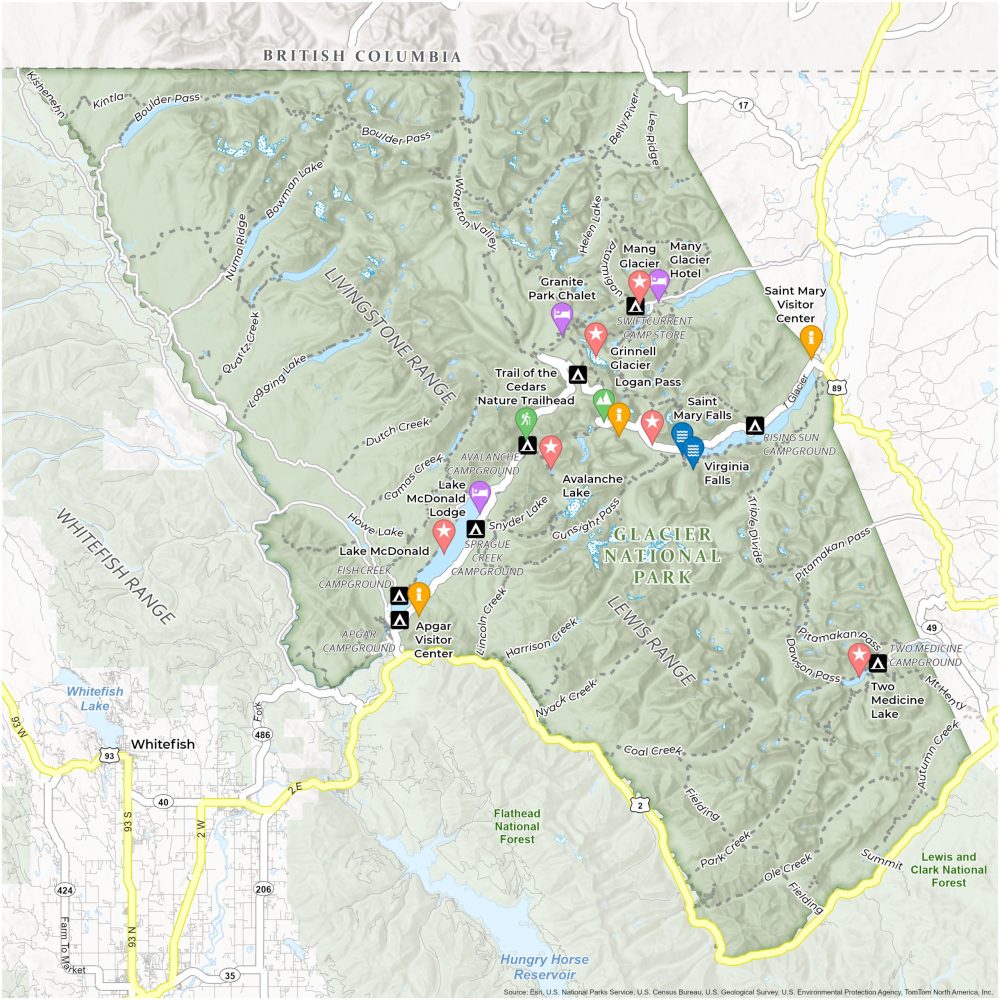

Glacier National Park. The name alone conjures images of colossal, snow-capped peaks, pristine alpine lakes, and the raw, untamed majesty of the "Crown of the Continent." Millions flock here annually, drawn by its ephemeral beauty and the promise of wild adventure. We trace its well-marked trails, consult modern topographical maps, and marvel at the engineering feat of Going-to-the-Sun Road. Yet, beneath this familiar surface lies an ancient tapestry of understanding, a profound connection to the land woven by generations long before the first park ranger, before the first surveyor, before the very concept of a "national park" existed. To truly experience Glacier, to truly comprehend its spirit, we must learn to read the land as its original custodians did: through the intricate, living maps of the Native American tribes who have called this sacred geography home for millennia.

This isn’t a review of a physical location you can pinpoint on Google Maps, but rather an invitation to "review" and re-experience Glacier National Park through an entirely different, richer lens. It’s about understanding the park not just as a collection of geological wonders, but as a living document, inscribed with the stories, routes, resources, and spiritual essence known intimately by the Blackfeet (Niitsítapi), Kootenai (Ktunaxa), and Salish (Séliš) peoples.

Beyond Cartography: What are Native American "Maps"?

When we speak of Native American "maps" in the context of Glacier, we aren’t referring to paper documents with grids and legends in the Western sense. Instead, these are comprehensive, multi-layered cognitive maps, passed down through oral tradition, song, ceremony, and practical demonstration. They are embodied knowledge, etched into memory and reinforced by the landscape itself.

These indigenous maps include:

- Oral Histories and Place Names: Every peak, valley, river, and lake had a name, often descriptive, sometimes narrating an event, a warning, or a spiritual significance. These names functioned as mnemonic devices, carrying vast amounts of information about resources, dangers, and sacred sites. For instance, what we know as Chief Mountain is known to the Blackfeet as Nínaiistáko, "Chief Mountain," but also embodies the spirit of a revered elder and a place of vision.

- Songlines and Ceremonial Routes: Certain songs acted as navigational guides, their verses describing landmarks and routes, sometimes over vast distances. Ceremonial paths, often tied to seasonal migrations or spiritual quests, were meticulously followed, their importance reinforcing the landscape’s sacredness.

- Star Charts and Celestial Navigation: The night sky was a primary map. Knowledge of constellations, planetary movements, and the sun’s path throughout the year allowed for precise navigation, especially during long journeys across featureless plains or through dense forests.

- Physical Markers: While less formal than modern signposts, cairns, blazed trees, and specific rock formations served as trail markers, indicating safe passages, water sources, or important hunting grounds.

- Resource Maps: Perhaps most critically, these "maps" encoded a deep understanding of ecological cycles: where and when to find berries, roots, fish, and game; the migration patterns of bison, deer, and elk; the locations of medicinal plants and suitable materials for tools and shelter. This knowledge ensured survival and sustainable living.

The Blackfeet (Niitsítapi): Guardians of the Backbone of the World

For the Blackfeet Nation, the eastern slopes of what is now Glacier National Park were, and remain, the Backbone of the World (Mistakis). Their traditional territory stretched from the North Saskatchewan River in Canada south to the Yellowstone River in Montana, and from the Rocky Mountains east across the plains. Glacier’s peaks, particularly the Two Medicine and St. Mary Valleys, were central to their spiritual and physical existence.

Their maps detailed routes for hunting mountain sheep and goats, for gathering medicinal plants in the high alpine meadows, and for vision quests in solitary, sacred places. The stories tied to these peaks, like the tale of Napi (Old Man) shaping the landscape, infused the mountains with deep cultural meaning. A journey through these lands wasn’t just physical transit; it was a re-engagement with ancestral narratives, a walk through a living history book. To them, the land was not merely property but a relative, a provider, a source of spiritual power.

The Kootenai (Ktunaxa) and Salish (Séliš): Traversing the Western Watersheds

On the western side of the park, the Kootenai and Salish peoples navigated the dense forests, powerful rivers like the Flathead, and numerous lakes. Their maps emphasized riverine travel, portages, and the locations of prime fishing spots. The Kootenai, with their distinctive sturgeon-nosed canoes, were expert navigators of the Flathead River system, their routes connecting them to vast trading networks that reached the Pacific coast.

Their knowledge included the best places to harvest huckleberries, dig camas roots, and hunt elk and deer in the lower valleys. Their oral traditions spoke of the creation of the lakes and the origins of the animals, guiding their relationship with the natural world. For these tribes, the mountains were not an impenetrable barrier but a resource-rich homeland, traversed with skill and reverence.

Experiencing Glacier Through Indigenous Eyes: A Traveler’s Guide

So, how can a modern traveler, armed with GPS and waterproof park maps, begin to access and appreciate these ancient layers of understanding? It requires a shift in perspective, a willingness to slow down, and an active engagement with the park’s deeper narrative.

- Visit the Blackfeet Reservation: The most direct way to connect with the living culture is to visit the adjacent Blackfeet Reservation, especially the Museum of the Plains Indian in Browning, or attend local pow-wows and cultural events (check schedules in advance). Here, you can encounter the contemporary vibrancy of the Niitsítapi people, learn about their history directly, and support their artists and businesses.

- Seek Out Interpretive Programs: Glacier National Park, recognizing the importance of indigenous history, increasingly offers ranger-led programs that incorporate Native American perspectives. Look for these at visitor centers or check the park’s activity schedule. Some programs might even feature tribal members as guest speakers, offering invaluable first-hand insights.

- Read and Research: Before or during your visit, delve into books and articles about the Blackfeet, Kootenai, and Salish peoples and their connection to this land. Authors like James Welch (Blackfeet) offer powerful perspectives. The park’s official website also provides resources. Understanding the specific stories associated with prominent peaks or valleys will transform them from mere geological features into living landmarks.

- Observe Place Names: While many indigenous place names were replaced by colonial ones, some persist, and understanding their original meanings can be enlightening. For example, learning the Blackfeet name for Chief Mountain and its significance adds a profound layer to its already imposing presence.

- Walk Ancient Paths: Many of Glacier’s hiking trails follow routes established by Native Americans over centuries. As you walk, imagine the journeys of those who came before you – not just as recreational hikers, but as hunters, gatherers, spiritual seekers, and traders. What would they have observed? What would their priorities have been?

- Reflect on the Landscape: Spend time simply sitting and observing. Listen to the wind, the water, the wildlife. Try to imagine how the landscape would have been read as a source of survival, not just scenic beauty. Consider the interdependencies of plants, animals, and humans. This contemplative approach can open a window to the holistic understanding inherent in indigenous maps.

- Support Indigenous Tourism: Look for opportunities to support Native American-owned businesses or cultural initiatives that promote authentic experiences and ensure the benefits of tourism reach the original communities.

The Enduring Legacy and Our Shared Responsibility

The imposition of colonial boundaries and the creation of Glacier National Park in 1910 dramatically altered the traditional way of life for these tribes, severing their access to ancestral lands and resources. Many sacred sites became inaccessible, and their traditional place names were often replaced. This history of displacement and cultural erasure is an uncomfortable but essential part of understanding the park’s narrative.

Yet, despite these challenges, the connection of the Blackfeet, Kootenai, and Salish peoples to this land remains unbroken. Their knowledge, stories, and spiritual ties endure. Today, there’s a growing movement towards reconciliation and collaboration, with the tribes playing an increasingly important role in park management, interpretation, and cultural preservation. The park’s very existence, in a sense, is a testament to the enduring power of these landscapes, which continue to resonate with the ancient "maps" that guided and sustained generations.

Conclusion: A Deeper Journey

Visiting Glacier National Park with an awareness of its Native American "maps" transforms the experience from a mere scenic tour into a profound journey through time and culture. The mountains cease to be just rocks and ice; they become storytellers, ancient guides, and sacred guardians. The rivers whisper not just of meltwater, but of ancestral journeys. The forests breathe with the knowledge of countless generations who understood every leaf and creature.

By actively seeking to understand and respect the indigenous perspectives, we don’t just add an extra layer of information to our trip; we unlock a deeper, more meaningful connection to one of the most magnificent places on Earth. We become more responsible travelers, more informed observers, and ultimately, more enriched by the enduring wisdom of those who first truly mapped and loved this incomparable landscape. So, the next time you gaze upon the soaring peaks of Glacier, listen closely. The echoes of ancient voices, guided by their living maps, are still there, waiting to be heard.