Forget the conventional GPS. Imagine a map that doesn’t just show roads and landmarks, but weaves in millennia of story, spirituality, and ecological wisdom. This is the realm of contemporary Indigenous cartography, and encountering a location through its lens isn’t just travel—it’s an immersion into the very soul of a place. For the discerning traveler seeking depth beyond the postcard, understanding and engaging with these profound mapping projects offers an unparalleled opportunity to truly "review" a destination, not just for its scenic beauty, but for its living history and the deep connection of its First Peoples.

This article reviews the experience of visiting places—specifically, the vast and ancient landscapes of Australia, which I’ll use as a primary example, though these principles apply globally—through the transformative perspective offered by contemporary Indigenous cartography projects. It’s a review not of a single site, but of a paradigm shift in how we perceive and interact with the land.

The Unseen Layers: What is Contemporary Indigenous Cartography?

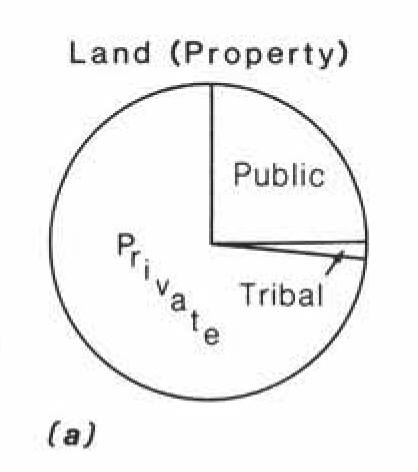

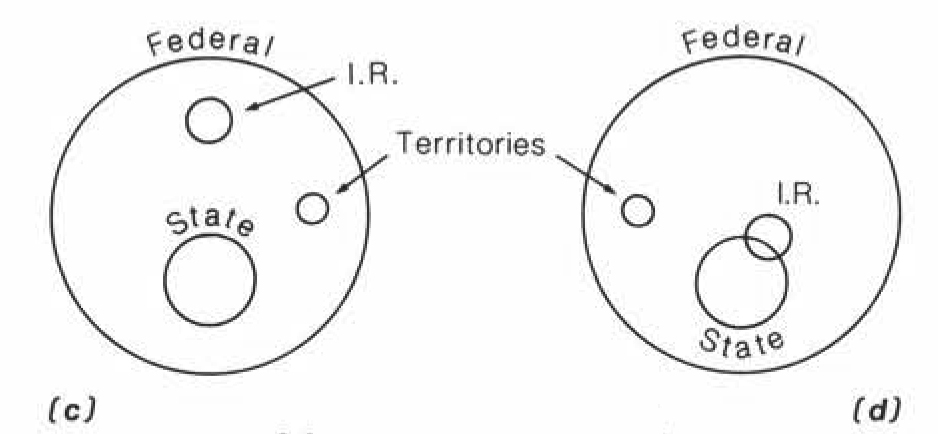

Contemporary Indigenous cartography is far more than just drawing lines on a paper. It’s the dynamic application of ancient knowledge systems, spiritual beliefs, and Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) using modern mapping technologies like Geographic Information Systems (GIS), satellite imagery, and GPS. It’s a powerful fusion, bridging the gap between ancestral memory and the digital age. These maps are not merely navigational tools; they are living documents of cultural heritage, land tenure, resource management, and identity.

In Australia, the concept of "Country" is central. For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, Country is not just land; it’s a sentient being, an intricate web of relationships encompassing land, water, air, ancestors, plants, animals, and people. It’s where spiritual beliefs, cultural practices, and identity are rooted. Traditional songlines, often seen as invisible pathways across the landscape, are themselves complex, multi-layered maps, detailing creation stories, sacred sites, resource locations, and ancestral journeys. Contemporary Indigenous cartography digitizes and revitalizes these songlines, making the invisible visible, and in doing so, reveals the profound meaning of a place that a standard topographic map simply cannot convey.

Why This Lens Transforms Your Travel Experience

1. Beyond the Surface: Unveiling Deep Meaning

When you visit a national park or a remote stretch of wilderness, a conventional map shows you trails, elevations, and points of interest. But an Indigenous-informed map, or the knowledge gained from understanding these projects, unveils layers of meaning. A rock formation isn’t just geology; it’s a creation ancestor. A waterhole isn’t just a source of hydration; it’s a sacred site, a place of spiritual power, or a vital community gathering point for millennia. This perspective transforms a scenic vista into a living narrative, making your journey infinitely richer. You’re not just seeing the land; you’re feeling its story.

2. A Deeper Connection to People and Culture

Engaging with contemporary Indigenous cartography inevitably leads to engaging with the Traditional Owners of the land. These projects are almost always community-led, driven by the desire to preserve and pass on knowledge, assert land rights, and manage their Country according to their traditions. As a traveler, this means opportunities for genuine cultural immersion. Instead of just observing, you can seek out tours led by Indigenous rangers who use these very maps to explain their connection to the land, their responsibilities, and the importance of specific sites. This fosters respectful interaction and a profound understanding of a culture deeply intertwined with its environment.

3. Ethical and Respectful Travel

In many parts of the world, particularly in settler-colonial nations like Australia, Canada, and the USA, land rights and sovereignty remain contentious issues. Indigenous mapping projects are often at the forefront of land claim efforts, demonstrating historical occupation and ongoing connection. As a traveler, understanding this context is crucial for ethical engagement. Knowing that the land you traverse has been cared for by specific peoples for tens of thousands of years, and that their knowledge of it is foundational, changes your relationship to the place. It encourages respectful visitation, adherence to cultural protocols, and an awareness of the ongoing struggles and triumphs of Indigenous communities.

4. Environmental Stewardship and Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK)

Indigenous peoples are often the world’s most effective conservationists, holding vast Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) passed down through generations. Contemporary Indigenous cartography is a vital tool for applying this knowledge to modern environmental challenges. For instance, in Australia’s Top End, Indigenous ranger groups use GIS to map fire regimes, monitor endangered species, track invasive plants, and manage water resources, all informed by millennia of observation and practice.

When you travel through these areas, appreciating the role of Indigenous mapping means understanding the landscape not just as "nature" but as a carefully managed ecosystem, sustained by human interaction and ancient wisdom. It reframes environmental issues, showing that sustainable practices are often deeply rooted in traditional ways of knowing and being.

Reviewing the Experience: Australia’s Living Maps

To truly review the experience of encountering a location through contemporary Indigenous cartography, let’s consider a hypothetical journey through parts of Australia’s vast northern territories—a region where these projects are particularly active and impactful.

Preparation: Before setting out, a traveler seeking this deeper engagement would look beyond standard guidebooks. They might research organizations like AIATSIS (Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies), regional land councils, or specific Indigenous ranger programs. Online resources often showcase community-led mapping projects, detailing their objectives and the cultural significance of their work. Seeking out Indigenous-owned tour operators is also key, as they are often directly connected to these knowledge systems.

On the Ground: The Transformation:

Imagine arriving in a remote area, perhaps in the Kimberley or Arnhem Land. A standard map might show a river, a mountain range, and a few dotted tracks. But with the insights from Indigenous cartography:

- The River: Is no longer just a body of water. Through the lens of an Indigenous map, or a guided explanation, it becomes a "Dreaming track" of a Rainbow Serpent, a creator being whose journey shaped the landscape and instilled it with sacred power. The bends in the river might correspond to specific events in the Dreamtime story, and certain banks might be traditional fishing grounds, meticulously managed for sustainability. Your perception shifts from a geographical feature to a living, spiritual artery.

- The Mountain Range: Isn’t just an elevation. It’s a place where ancestors rested, where significant ceremonies were held, or where specific resources like ochre for painting are found. An Indigenous map might highlight sacred sites, traditional pathways for seasonal migrations, or areas of cultural significance that are not to be disturbed. Suddenly, hiking through these ranges becomes an act of walking through a vast, open-air museum, each step imbued with history and reverence.

- The Bush: Is not just "empty" wilderness. It’s a meticulously managed larder and pharmacy. Contemporary Indigenous maps, often used by ranger groups, detail the locations of bush tucker (native foods) in season, medicinal plants, and water sources known only to Traditional Owners. These maps also track the impact of controlled burning, a practice dating back millennia, used to regenerate the land, prevent catastrophic wildfires, and encourage new growth for animals. Observing this management firsthand, perhaps on a guided walk, reveals a sophisticated land management system that far predates Western science.

The Martu Example: The Martu people of Western Australia offer a compelling real-world example. Their traditional lands span vast desert areas. Using satellite imagery and GIS, Martu elders have mapped their traditional water sources (rock holes, soaks), their fire management zones, and their knowledge of bilby and other threatened species habitats. This mapping is critical for managing their country, applying traditional burning practices, and asserting their native title rights. A traveler encountering Martu country with an awareness of these maps would see not a barren desert, but a vibrant, interconnected ecosystem, understood and managed with astonishing precision.

The Kowanyama Rangers: In far north Queensland, the Kowanyama Aboriginal Land and Natural Resources Management Office uses GIS to map traditional hunting areas, monitor turtle and dugong populations, and manage country. Their maps are vital for protecting their cultural heritage and sustaining their livelihoods. A traveler engaging with the Kowanyama Rangers would gain invaluable insights into the delicate balance of their coastal and riverine ecosystems, informed by generations of intimate knowledge.

Challenges and Considerations for the Traveler

While the rewards are immense, engaging with contemporary Indigenous cartography and the communities behind it requires thoughtfulness:

- Respect for Sacred Sites: Not all knowledge is for public consumption. Many maps, or parts of maps, contain restricted information about sacred sites or ceremonies, accessible only to initiated members of the community. Travelers must always respect these boundaries and never trespass on restricted areas.

- Intellectual Property: The knowledge embedded in these maps is the intellectual property of Indigenous communities. Support their initiatives ethically, through official tours or direct contributions, rather than seeking to extract information without permission or compensation.

- Avoiding "Cultural Tourism" Pitfalls: Ensure your engagement is genuine and reciprocal, not merely a superficial consumption of culture. Listen, learn, and be prepared to be challenged in your preconceptions.

- The Ongoing Struggle: Remember that these mapping projects are often part of a larger struggle for self-determination, land rights, and cultural survival. Be an ally by understanding and respecting these contexts.

Conclusion: A Journey of Profound Understanding

Reviewing a location through the lens of contemporary Indigenous cartography is not just a travel hack; it’s a profound shift in perspective. It transforms a landscape from a mere physical space into a dynamic, living entity imbued with history, spirituality, and ecological wisdom. It moves the traveler beyond superficial observation to deep engagement, fostering respect, understanding, and a genuine connection to the land and its First Peoples.

For the traveler seeking more than just sights, for those who crave a journey that nourishes the mind and soul, seeking out and appreciating the power of contemporary Indigenous cartography projects is an absolute imperative. It’s an invitation to see the world not just as it appears on a conventional map, but as it truly is: a tapestry of interconnected stories, meticulously charted and lovingly cared for by those who have called it home for millennia. This is the ultimate travel review – not of a place, but of the transformative experience of seeing a place with new, ancient eyes.