Mapping Resilience: The Enduring Legacy of the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde, Oregon

A map is rarely just a collection of lines and labels; for Indigenous peoples, it is a living document, a testament to ancestral presence, profound loss, and enduring resilience. For the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde (CTGR) in Oregon, their map is an intricate tapestry woven with centuries of history, identity, and an unwavering spirit of self-determination. Far from a static cartographic representation, it is a dynamic narrative that invites us to delve into the complex, often painful, but ultimately triumphant story of over two dozen distinct tribes and bands forcibly brought together, who forged a new, powerful collective identity.

This article explores the map of the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde not merely as a geographical guide but as a portal into their rich history, their journey through dispossession and forced removal, their fight for survival, and their powerful resurgence. For the mindful traveler and the history enthusiast, understanding this map is essential to appreciating the true landscape of Oregon—a landscape shaped as much by Indigenous heritage as by settler narratives.

The Grand Ronde Map: More Than Cartography

When one encounters a map associated with the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde, it’s crucial to understand what it should represent, beyond just current reservation boundaries. A comprehensive CTGR map speaks volumes:

- Ancestral Territories: It outlines the vast, diverse ancestral lands of the more than 27 tribes and bands that now comprise the CTGR. These lands stretched across the Willamette Valley, the Coast Range, and parts of Southern Oregon, encompassing varied ecosystems from dense forests and fertile river valleys to the rugged Pacific coastline. This pre-contact map illustrates a mosaic of distinct cultures, languages, and lifeways, each intimately connected to their specific environment.

- Treaty-Ceded Lands: Crucially, the map would delineate the immense tracts of land ceded under duress through a series of treaties in the mid-19th century. These are the lands that now make up much of Western Oregon. This stark contrast between ancestral domain and ceded territory highlights the scale of land dispossession.

- The Grand Ronde Reservation: It marks the original 61,000-acre reservation established in 1856, a fraction of their former territories, and then the drastically reduced footprint after the General Allotment Act of 1887. Finally, it shows the current, restored reservation lands, a testament to their successful fight for federal recognition and land reacquisition.

- Cultural and Historical Sites: While not always explicitly labeled on every map, understanding the CTGR map implicitly points to countless sacred sites, traditional resource gathering areas, historic village locations, and the forced migration routes—the "Oregon Trail of Tears"—that led their ancestors to Grand Ronde.

This map, therefore, is not a simple guide to navigating the physical terrain; it is a guide to navigating history, identity, and the ongoing journey of a sovereign nation.

A Tapestry of Nations: The "Who" of the CTGR

The "Confederated" aspect of the Tribes of Grand Ronde is central to their identity and story. Unlike many single-nation reservations, Grand Ronde was specifically created as a crucible, a holding pen for disparate peoples displaced from their homelands. Beginning in the 1850s, the U.S. government forcibly relocated numerous distinct tribes and bands from across Western Oregon to this single, relatively small reservation.

Among the many peoples who found themselves suddenly neighbors were:

- Kalapuya: From the fertile Willamette Valley.

- Molalla: From the foothills of the Cascade Mountains.

- Umpqua and Rogue River Tribes: From Southern Oregon, survivors of brutal conflicts.

- Chinook and Clackamas: From the lower Columbia River and its tributaries.

- Tillamook and Nestucca: From the Oregon Coast.

- And many others: Including bands of Shasta, Takelma, and various Athapaskan-speaking groups.

Each of these nations possessed unique languages, governance structures, spiritual beliefs, and subsistence practices tailored to their specific environments. The map of their ancestral lands, therefore, would have shown a rich, complex mosaic of overlapping territories and distinct cultural markers. The trauma of forced removal meant that these diverse peoples, many of whom had previously been strangers or even occasional adversaries, were now compelled to coexist, adapt, and eventually, forge a new, shared identity within the confines of Grand Ronde.

The Weight of Treaties and Removal: How the Map Changed

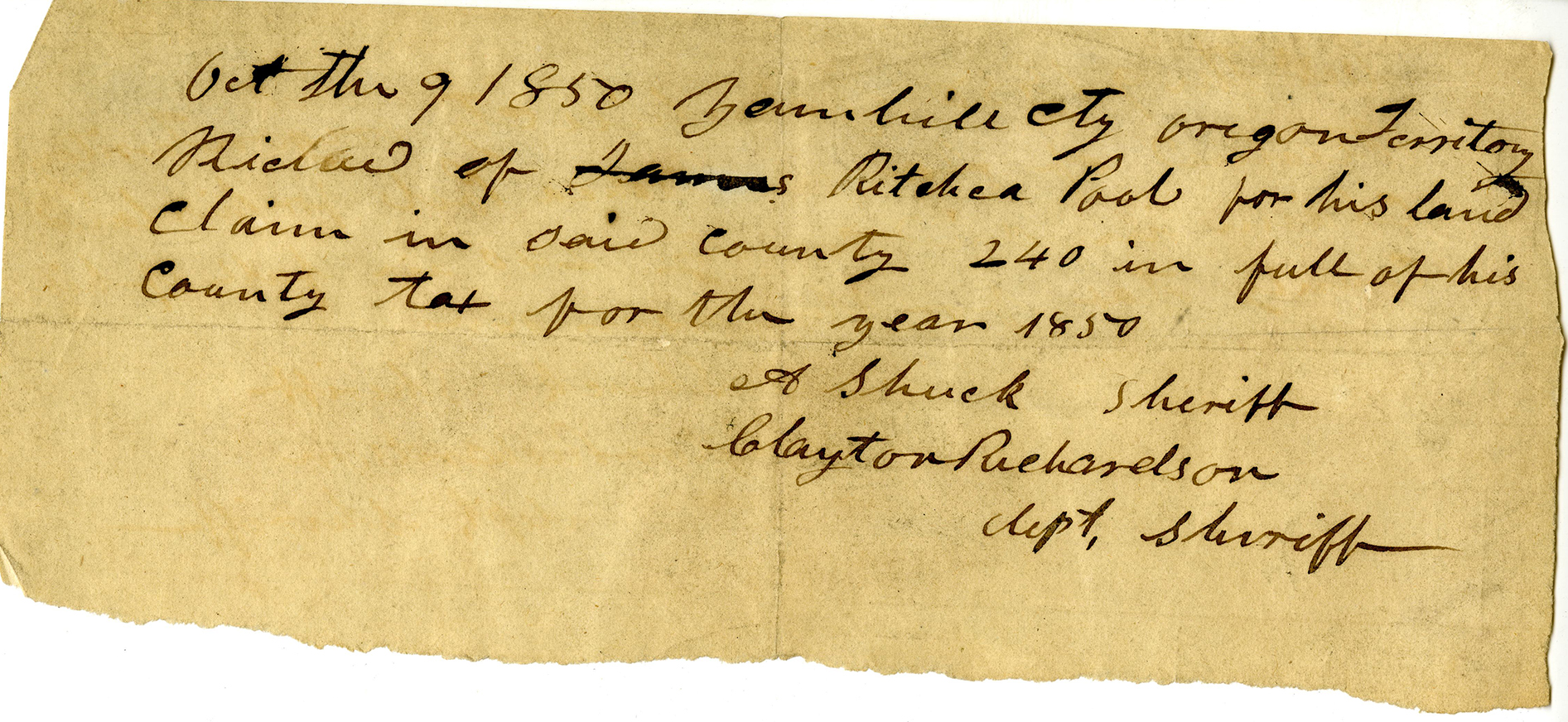

The mid-19th century brought an aggressive wave of American settlement to Oregon, spurred by the Oregon Trail and the Donation Land Claim Act of 1850, which encouraged white settlers to claim vast tracts of Indigenous land. This era ushered in a period of intense pressure, conflict, and ultimately, forced treaty-making.

Between 1853 and 1855, U.S. treaty commissioners, often employing coercion and deceit, negotiated a series of treaties with the Indigenous peoples of Western Oregon. These treaties, frequently misunderstood or misrepresented to the tribal leaders, resulted in the cession of millions of acres of ancestral land. In exchange, the tribes were promised small reservations and annuities—promises that were often broken.

The map dramatically transformed during this period. The expansive, interconnected territories of the Indigenous nations were replaced by isolated dots: the newly designated Grand Ronde and Siletz Reservations. The period of forced removal, often referred to as the "Oregon Trail of Tears," saw thousands of people, from infants to elders, marched hundreds of miles from their homes to the reservations. Many perished from disease, starvation, and exposure along the way. The establishment of the Grand Ronde Reservation in 1856 was not a benevolent act, but a calculated effort to clear land for white settlement and control the remaining Indigenous population.

Survival and Resilience: Forging a New Grand Ronde Identity

Life on the Grand Ronde Reservation was a profound test of survival. The U.S. government’s policies aimed at assimilation, actively suppressing Indigenous languages, spiritual practices, and traditional governance. Children were sent to boarding schools, forbidden to speak their native tongues. Despite these immense pressures, the diverse peoples of Grand Ronde began the arduous process of adapting and building a new community.

Intermarriage among the different tribal groups became common, fostering new kinship ties. Shared experiences of loss, hardship, and the fight for cultural continuity gradually forged a distinct "Grand Ronde" identity. A vital element in this process was the emergence of Chinuk Wawa (also known as Chinook Jargon or Wawa Lipt), a trade pidgin that became the lingua franca on the reservation. This shared language allowed different tribes to communicate, facilitating the development of a unified community and preserving elements of their collective Indigenous heritage.

Even as they built this new identity, further land loss occurred. The General Allotment Act of 1887 broke up communal reservation lands into individual parcels, with "surplus" lands then sold off to non-Native settlers. By 1954, the original 61,000-acre reservation had shrunk to a mere 300 acres of tribally owned land. The map shrank further, mirroring the erosion of their land base and sovereignty.

Termination and Restoration: The Fight for Existence

The mid-20th century brought another devastating blow: the federal policy of "Termination." In the 1950s, the U.S. government unilaterally ended its trust relationship with over 100 Native American tribes, including the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde in 1954. This policy was catastrophic. It stripped tribes of their federal recognition, abolished their reservations, ended essential services, and led to the sale of their remaining lands. For Grand Ronde, it meant the dissolution of their sovereign status and a desperate struggle for survival without any federal support.

Despite the profound challenges, the people of Grand Ronde refused to disappear. For nearly three decades, tribal members, led by visionary leaders like Kathryn Harrison, organized, advocated, and tirelessly fought for the restoration of their federal recognition. Their struggle was a testament to their deep-seated identity and commitment to their heritage.

On November 18, 1983, their perseverance paid off. Congress passed the Grand Ronde Restoration Act, officially restoring the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde to federal recognition. This monumental achievement marked a turning point, allowing the Tribe to begin the arduous work of rebuilding their nation, reacquiring ancestral lands, and revitalizing their culture. The map, once again, began to expand, not to its original ancestral vastness, but to a new, sovereign territory under tribal stewardship.

The Map Today: A Living Document of Sovereignty and Future

Today, the map of the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde reflects a powerful story of resurgence and self-determination. It illustrates:

- Restored Reservation Lands: While still a fraction of their ancestral domain, the map highlights the current 12,000+ acres of tribally owned trust land that constitute the Grand Ronde Reservation. This land base is crucial for their economic, cultural, and political sovereignty.

- Economic Enterprises: A modern CTGR map would likely feature key tribal enterprises, most notably the Spirit Mountain Casino. Established in 1995, it is the largest employer in Polk County and a vital source of revenue that funds tribal government, health services, education, housing, and cultural programs. These enterprises represent economic sovereignty—the ability to generate wealth and manage resources for the benefit of their people, rather than relying on federal appropriations.

- Cultural and Educational Hubs: The map points to the Chachalu Museum and Cultural Center, a vibrant institution dedicated to preserving and sharing the history, languages, and traditions of the Grand Ronde people. It also signifies the tribal government offices, health clinic, and educational facilities that serve the community.

- Land Stewardship and Environmental Efforts: The CTGR are active participants in land management, environmental restoration, and salmon habitat recovery across their ancestral lands, often collaborating with state and federal agencies. Their map implicitly shows areas of ecological importance where their traditional knowledge guides modern conservation efforts.

The contemporary Grand Ronde map is a dynamic representation of a thriving, self-governing nation. It speaks to an ongoing commitment to cultural revitalization, with significant investments in language immersion programs (Chinuk Wawa), traditional arts, and ceremonies. It demonstrates political influence, with the Tribe actively engaging in local, state, and federal policy discussions. Most importantly, it signifies a future built on the foundations of their ancestors’ resilience and vision.

Experiencing the Grand Ronde Legacy: A Guide for Travelers and Learners

For those traveling through Oregon, understanding the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde map and their story transforms the landscape. It encourages a deeper, more respectful engagement with the land and its original inhabitants.

- Visit the Chachalu Museum and Cultural Center: Located on the Grand Ronde Reservation, this is an essential stop. It offers powerful exhibits, historical context, and educational programs that directly connect to the narratives embedded in the CTGR map. It’s a place to learn about their languages, stories, and the journey of their ancestors.

- Acknowledge the Land: As you travel through Western Oregon, take a moment to acknowledge that you are on the ancestral lands of the various tribes that now form the CTGR. This simple act of recognition honors their enduring presence and historical connection to the land.

- Support Tribal Enterprises: Patronizing businesses like the Spirit Mountain Casino or other tribal ventures contributes directly to the well-being and self-sufficiency of the Grand Ronde community.

- Engage with Respect: If you have the opportunity to attend a public event (such as a powwow, if open to the public), do so with an open heart and a commitment to respectful observation and learning.

- Educate Yourself: The CTGR website (www.grandronde.org) is a rich resource for further learning about their history, government, and cultural programs. Understanding their journey enriches any visit to Oregon.

Conclusion

The map of the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde is not merely a cartographic representation of land; it is a profound testament to survival, adaptation, and unwavering identity. It charts the pre-contact world of diverse nations, the devastating impact of forced removal and treaties, the crucible of reservation life, the existential threat of termination, and the triumphant resurgence of a sovereign people.

For the mindful traveler and the student of history, this map serves as a vital tool for understanding Oregon’s true narrative—one that acknowledges the immense losses suffered by Indigenous peoples, but also celebrates their extraordinary resilience and the enduring strength of their cultures. The CTGR map is a living document, constantly being re-drawn by the vibrant present and hopeful future of a people who have overcome immense adversity to reclaim their place on the land and in the world. It reminds us that history is not static, and the stories embedded in the landscape continue to shape who we are and where we are going.