Chaco Canyon: Where the Earth Itself Becomes an Anasazi Map

Forget the folded paper maps we consult on our smartphones. To truly understand the Ancestral Puebloans, often referred to as the Anasazi, one must shed modern cartographic assumptions and embrace a world where the landscape itself, the stars above, and the very architecture of a civilization served as a living, breathing map. And nowhere is this profound spatial understanding more palpable, more awe-inspiring, than at Chaco Culture National Historical Park in New Mexico.

This isn’t a review of a place with Anasazi maps; it’s a deep dive into a place that is an Anasazi map. Chaco Canyon isn’t just a collection of ruins; it’s a meticulously engineered blueprint of the Ancestral Puebloan cosmos, a testament to their sophisticated grasp of astronomy, geology, and social organization. Visiting Chaco is not merely walking through ancient structures; it’s walking through a three-dimensional, deeply spiritual map of an advanced civilization that flourished over a thousand years ago.

The Journey to the Map’s Heart: Reaching Chaco

The journey itself is part of the experience, a pilgrimage that immediately sets the tone. Chaco Canyon is remote, deliberately so it seems, nestled in the stark, high desert of northwestern New Mexico. Paved roads eventually give way to unpaved, often washboarded dirt tracks that test both vehicle and resolve. This isn’t a place you stumble upon; it’s a destination you commit to, an effort that amplifies the sense of discovery once you arrive. The isolation is key – it preserves the profound silence that allows one to truly listen to the whispers of the past. There’s no cell service, no bustling tourist infrastructure, just the vast sky, the ancient stones, and an overwhelming sense of time.

Deconstructing the Anasazi Map: Beyond the Parchment

Our modern minds often equate maps with two-dimensional representations on paper or screens. For the Ancestral Puebloans, maps were multifaceted, deeply embedded in their oral traditions, their ceremonial practices, and their physical environment. They were:

- Celestial Maps: The sky was their clock, calendar, and compass. They observed the sun, moon, and stars with astonishing precision. Solstices and equinoxes were marked not just ceremonially, but architecturally.

- Terrestrial Maps: These weren’t drawn lines, but physical pathways – vast road networks connecting distant communities, trade routes, and sacred sites. They were also the natural features of the landscape: mountains, mesas, canyons, and water sources, all understood and integrated into their spatial memory.

- Architectural Maps: The Great Houses of Chaco Canyon weren’t randomly placed. Their orientation, internal layouts, and relationships to one another encode astronomical alignments, cardinal directions, and perhaps even social hierarchies. Each structure, in essence, was a fixed point on their grand map.

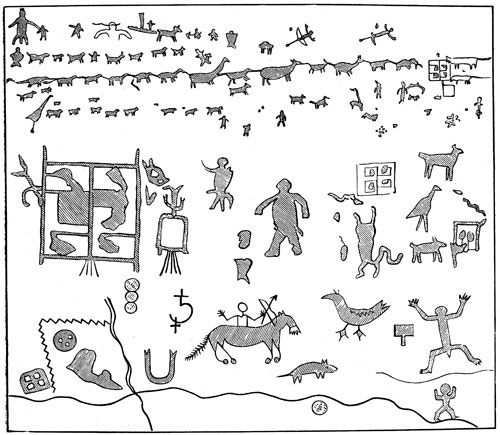

- Symbolic/Spiritual Maps: Petroglyphs and pictographs, while sometimes recording events or observations, often served as symbolic representations of their world, their cosmology, and their journey through life. These were often found at significant points in the landscape, acting as markers or guideposts.

Chaco Canyon: A Masterpiece of Spatial Engineering

Stepping into Chaco Canyon is to step into the heart of this mapping system. The Great Houses here – Pueblo Bonito, Chetro Ketl, Kin Kletso, Casa Rinconada, and many others – are not merely impressive ruins; they are grand statements of a civilization’s understanding of its place in the cosmos.

Pueblo Bonito: The Grand Central Station of the Map

Pueblo Bonito, the largest and most famous of the Chacoan Great Houses, is an architectural marvel and arguably the most complex physical map within the canyon. Its D-shaped structure, built with exquisite masonry over three centuries, housed hundreds of rooms and dozens of kivas. But its true genius lies in its orientation. The central wall of Pueblo Bonito is aligned almost perfectly north-south, serving as a meridian. Its corners align with cardinal directions. The entire structure appears to be carefully positioned to capture specific solar and lunar events, turning the building itself into an observatory and a calendar. Walking through its vast courtyards, one can sense the deliberate planning, the way light and shadow play at crucial times, revealing a deep understanding of time and space.

The Chacoan Roads: Arteries of a Civilization’s Map

Beyond the structures, the most striking evidence of the Anasazi’s terrestrial mapping prowess is the Chacoan road system. Imagine an intricate network of perfectly straight roads, some extending for dozens of miles, radiating out from Chaco like arteries from a beating heart. These weren’t mere trails; they were engineered pathways, up to 30 feet wide, often built with curbing and ramps, traversing challenging terrain with astonishing precision.

These roads connected Chaco Canyon to over 150 outlying communities, or "outliers," creating a vast economic, political, and ceremonial network across the Four Corners region. For the Ancestral Puebloans, these roads weren’t just a means of transport; they were a physical manifestation of their understanding of the landscape, connecting communities, resources, and sacred sites – a vast, terrestrial map etched into the very earth. They imply a centralized authority, a shared vision, and an astonishing ability to coordinate massive public works.

Celestial Alignments: Mapping the Cosmos

The most famous celestial map at Chaco is arguably the "Sun Dagger" on Fajada Butte. While access to the site is restricted to protect it, its significance as a solar calendar is well-documented. On the summer solstice, a dagger of light pierces a spiral petroglyph, perfectly bisecting it. On the equinoxes, two daggers frame the spiral. This ingenious device demonstrates a sophisticated understanding of astronomical cycles, allowing the Chacoans to accurately track the seasons, crucial for agricultural planning and ceremonial timing.

But celestial mapping wasn’t limited to Fajada Butte. Many of the Great Houses, particularly their Great Kivas (large, circular subterranean ceremonial chambers), are aligned to solstices and equinoxes. Casa Rinconada, a freestanding Great Kiva, has precisely aligned doorways and niches that mark the cardinal directions and the rising and setting points of the sun at critical times of the year. These structures are not just places of worship; they are physical manifestations of their cosmic understanding, fixed points on their celestial map.

Petroglyphs and Pictographs: Symbolic Map Markers

Scattered throughout the canyon, on cliff faces and boulders, are petroglyphs and pictographs. While their exact meanings are often debated, many scholars interpret them as more than mere art. Some depict constellations, others record significant astronomical events (like the A.D. 1054 supernova, often identified by a star and a crescent moon image). Spirals, zigzags, and human-like figures could represent migration paths, water sources, or spiritual journeys – serving as symbolic map markers or narratives of their world. These aren’t maps in the literal sense, but they are crucial elements of the Ancestral Puebloans’ way of knowing and representing their landscape and cosmos.

The Experience: Walking Through the Map

Visiting Chaco is an immersive experience that deepens one’s appreciation for these ancient maps. Hiking the trails that wind between the Great Houses, one feels the scale of their ambition. Climbing to the mesa tops, one gains a panoramic view of the canyon, appreciating how each structure relates to the others and to the broader landscape.

The silence is profound, broken only by the wind or the call of a raven. This quiet allows for contemplation, for imagining the bustling life that once filled these spaces. At night, the absence of light pollution reveals a sky teeming with stars, the very celestial map the Ancestral Puebloans gazed upon. It’s under this same sky that their world clicked into place, where their architectural alignments found their meaning.

You realize that the "map" isn’t just about finding your way from point A to point B; it’s about understanding your place in the universe. It’s about a deep, reciprocal relationship with the land and the sky.

Why Chaco Matters: A Legacy of Ingenuity

Chaco Canyon stands as a monumental testament to the ingenuity, astronomical knowledge, and organizational skills of the Ancestral Puebloans. It was a cultural and ceremonial hub, a center of innovation, and a nexus of trade across the Southwest. The decline of Chaco, likely due to a prolonged drought and resource depletion, led to the dispersal of its people, but their knowledge, their traditions, and their mapping principles continued, influencing subsequent Pueblo cultures.

For modern travelers, Chaco offers more than just a glimpse into the past. It offers a re-evaluation of how we understand our world, how we orient ourselves, and how we relate to the environment. It challenges us to look beyond the obvious, to see the deeper patterns and connections that exist all around us.

Practical Considerations for Your Journey to the Map

- Getting There: Chaco is remote. Access is primarily via unpaved roads (CR 7900 from US 550 or CR 7950 from NM 371). A high-clearance vehicle is recommended, especially after rain. Check road conditions with the park service before you go.

- Best Time to Visit: Spring and fall offer the most pleasant weather for hiking. Summers can be intensely hot, and winters cold. Stargazing is exceptional year-round due to minimal light pollution, but clear nights are best.

- What to Bring: Abundant water (no potable water sources in the park), sun protection (hat, sunscreen), sturdy hiking shoes, layers of clothing (temperatures can fluctuate wildly), a flashlight/headlamp for night exploration (and if camping), and all your food and supplies.

- Accommodation: The park has a small campground (Gallo Campground), which fills up quickly. Reservations are highly recommended. Otherwise, the nearest lodging is in Farmington or Cuba, New Mexico, both over an hour’s drive away.

- Respect the Site: Chaco is a sacred place to many contemporary Pueblo peoples. Stay on marked trails, do not climb on walls, and leave all artifacts undisturbed.

- Time Commitment: Plan for at least one full day, preferably two, to truly explore the major sites and absorb the atmosphere. The Great Houses are spread out, and walking between them is part of the experience.

The Final Word

Chaco Canyon isn’t just a destination; it’s an education. It’s an opportunity to walk through an ancient civilization’s most profound "map," a landscape where every stone, every alignment, every celestial event held meaning. It is a place that humbles, inspires, and ultimately, helps you redefine what a map truly is: not just a tool for navigation, but a canvas for understanding our place in the grand tapestry of existence. If you seek a journey that transcends mere sightseeing, one that offers a profound connection to human ingenuity and the ancient wisdom of the land, then Chaco Canyon awaits. Prepare to be mapped, and to be transformed.