Tracing the Invisible Map: The Cayuga Nation’s Historical Lands in New York

New York State, a vibrant tapestry of urban sprawl and natural beauty, holds a profound and often overlooked history etched into its very soil: the ancestral lands of the Haudenosaunee, or Iroquois Confederacy. Among its six nations, the Cayuga (Gayogo̱hó꞉nǫʼ) stand as a poignant example of resilience and enduring identity against centuries of dispossession. For travelers exploring the stunning Finger Lakes region, understanding the Cayuga Nation’s historical lands is not just an academic exercise; it’s an essential lens through which to appreciate the landscape, its names, and the living history that continues to shape it. This article delves into the historical map of the Cayuga Nation, exploring their pre-colonial sovereignty, the devastating impact of colonization, and their ongoing fight for recognition and land.

The Heart of the Haudenosaunee: Cayuga Homeland and Culture

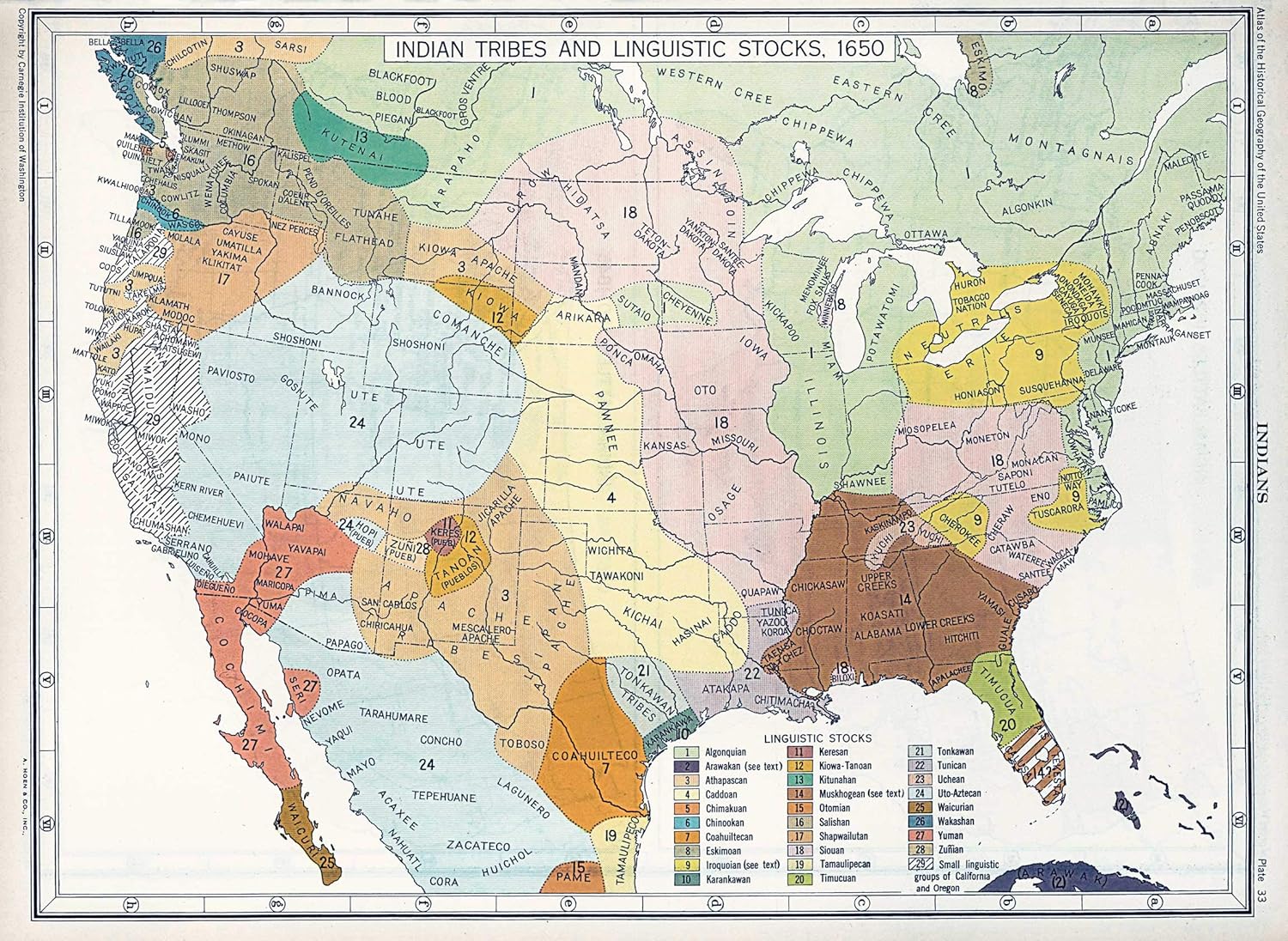

Before European contact, the Cayuga Nation occupied a central position within the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, residing primarily in the area between Cayuga Lake and Seneca Lake, extending westward towards the Genesee River and eastward to the Unadilla River. Their territory encompassed much of what is now the Finger Lakes region, a land rich in resources and spiritual significance. The Cayuga were known as the "People of the Great Swamp" or "People of the Mucky Land," a reference to the marshlands and fertile soils around their primary lake, Gayogo̱hó꞉nǫʼ (Cayuga Lake).

As one of the original five nations (Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, and Seneca) that formed the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, the Cayuga played a crucial role in maintaining the Great Law of Peace (Kaianere’kó:wa). Their central location meant they were vital intermediaries and keepers of the confederacy’s protocols. Their villages, like Gayagaanha (Cayuga Castle) and Chonodote (Canoga), were sophisticated settlements, characterized by longhouses, agricultural fields of corn, beans, and squash (the "Three Sisters"), and intricate social structures governed by clan mothers and chiefs. Their deep connection to the land wasn’t just economic; it was spiritual, foundational to their identity, language, ceremonies, and oral traditions. Every stream, hill, and forest held a name and a story, reflecting a profound reciprocal relationship with their environment.

The Crucible of Conflict: European Arrival and the American Revolution

The arrival of Europeans in the 17th century introduced a new era of profound change. Initial interactions with Dutch, French, and later British traders brought new goods, but also new diseases and geopolitical complexities. The Haudenosaunee, including the Cayuga, initially navigated these relationships as powerful, sovereign nations, engaging in diplomacy, trade, and strategic alliances to protect their interests and territory.

However, the 18th century brought escalating conflicts that irrevocably altered the landscape of Indigenous sovereignty. The French and Indian War (Seven Years’ War, 1754-1763) saw the Haudenosaunee attempting to maintain neutrality or strategically align with powers they believed would best preserve their lands and autonomy. Yet, it was the American Revolution (1775-1783) that proved to be the most devastating turning point for the Cayuga and the Confederacy as a whole.

Caught between the warring British and American factions, the Haudenosaunee Confederacy faced an impossible choice, ultimately leading to its division. While some Oneida and Tuscarora sided with the American colonists, the majority of the Mohawk, Onondaga, Cayuga, and Seneca Nations allied with the British Crown, honoring existing treaties and believing the British were more likely to respect their land rights. This decision sealed their fate in the eyes of the nascent United States.

In retaliation for their alliance with the British, General George Washington authorized the Sullivan-Clinton Expedition in 1779. This brutal military campaign, led by Generals John Sullivan and James Clinton, was explicitly designed to destroy the Haudenosaunee nations, eliminate their capacity to wage war, and break their morale. American forces systematically marched through the Cayuga heartland, burning villages, destroying vast fields of corn, beans, and squash, and leveling fruit orchards. The Cayuga people, driven from their homes, faced starvation, displacement, and immense loss. This was not merely a military victory; it was an act of scorched-earth policy aimed at dispossessing the Haudenosaunee from their ancestral lands, clearing the way for American expansion. The historical map of Cayuga territory, once teeming with life and culture, was rendered desolate by the fires of war.

The Erosion of Territory: Treaties and Dispossession

Following the American Revolution, the newly formed United States and the State of New York aggressively pursued policies of land acquisition that further dispossessed the Cayuga Nation. The Treaty of Fort Stanwix in 1784, intended to establish peace and define boundaries, was largely seen by the Haudenosaunee as coercive, signed under duress, and did not reflect their true intentions regarding land cessions.

New York State, acting independently and in direct violation of federal laws like the Indian Nonintercourse Act of 1790 (which required federal approval for all land transactions with Native American nations), engaged in a series of highly questionable treaties and purchases with individual Cayuga leaders or factions. These transactions often involved small sums of money or goods and were not ratified by the full Cayuga Nation or the federal government, rendering them illegal under U.S. law.

Key among these "sales" were the Treaties of 1789 and 1795, which effectively stripped the Cayuga of nearly all their remaining lands in New York. The 1789 "treaty" purported to cede all Cayuga lands to New York State, reserving only a 100-square-mile "reservation" (a mere fraction of their traditional territory) near the northern end of Cayuga Lake. Just six years later, the 1795 "treaty" saw New York "purchase" this remaining reservation, leaving the Cayuga Nation virtually landless within its ancestral territory. The narrative was clear: the state wanted the land, and it used any means necessary to acquire it, paving the way for non-Native settlement and the development of towns like Auburn, Ithaca, and Geneva. The historical map transformed from one of Cayuga sovereignty to one of encroaching colonial grids and property lines.

A Nation Divided: Diaspora and Resilience

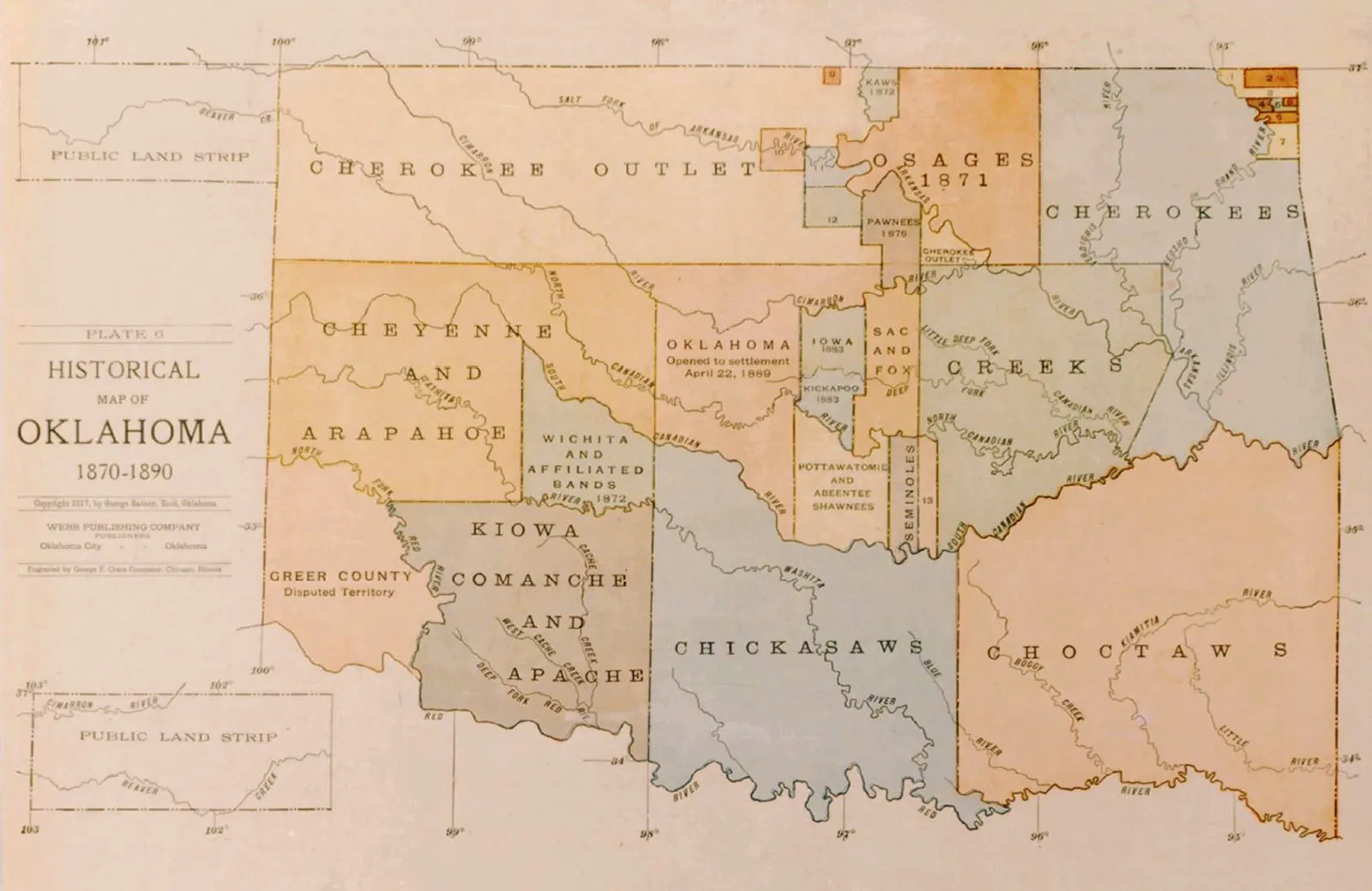

The loss of their ancestral lands forced the Cayuga people into a painful diaspora. Without a land base to sustain their traditional way of life, many sought refuge elsewhere. A significant portion of the Cayuga migrated north to Canada, settling on the Six Nations of the Grand River Reserve in Ontario, established by the British for their Haudenosaunee allies. Others moved westward, joining other Haudenosaunee nations, eventually settling in Oklahoma as part of the Seneca-Cayuga Nation.

While these communities flourished, maintaining Cayuga culture and identity in new territories, a smaller but persistent number of Cayuga remained in New York. Scattered, often living on the fringes of non-Native society or on other Haudenosaunee reservations (such as the Seneca Nation’s Cattaraugus or Allegany Reservations, or the Onondaga Nation Territory), they steadfastly held onto their heritage, language, and the dream of returning to their homeland. This division, born of dispossession, created complex challenges for the nation’s governance, unity, and efforts to reclaim their identity and land in New York. The historical map now depicted not just physical boundaries, but also the dispersed paths of a people determined to survive.

Reclaiming Identity and Land: Modern Struggles

The 20th century saw the Cayuga Nation of New York embark on a determined struggle for recognition and justice. In 1980, the Cayuga Nation of New York filed a landmark land claim against the State of New York, alleging that the 1795 "treaty" was illegal under the 1790 Indian Nonintercourse Act. This claim sought compensation for the illegal taking of their lands and the return of some of their ancestral territory.

The legal battle was long and arduous. In 2001, a federal jury awarded the Cayuga Nation $248 million in damages for the illegal land dispossession. However, this monetary award was later overturned on appeal, leaving the Cayuga without the financial compensation. Despite these legal setbacks, the Cayuga Nation has continued its efforts to re-establish a land base in its traditional territory. Through strategic land purchases, often with the support of federal funds, the Cayuga Nation has slowly begun to acquire parcels of land in Seneca Falls and Union Springs, near their ancestral Cayuga Lake. These acquisitions, though modest compared to their original territory, are profoundly significant. They represent tangible steps towards rebuilding community, asserting sovereignty, and re-establishing their spiritual connection to the land.

The modern "map" of the Cayuga Nation in New York is complex, marked by a patchwork of small, tribally-owned parcels interspersed within non-Native private and public lands. These efforts, however, are not without internal challenges. The Cayuga Nation has faced significant internal leadership disputes and political divisions in recent decades, which have complicated land management, federal recognition efforts, and the unified pursuit of their goals. These internal struggles, while painful, are also a testament to the enduring vitality and passion within the Cayuga community to define their future on their own terms.

Conclusion: Echoes of the Past, Hopes for the Future

For the discerning traveler and history enthusiast exploring the Finger Lakes region today, the Cayuga Nation’s historical lands offer an invaluable perspective. The rolling hills, shimmering lakes, and fertile valleys are not just picturesque scenery; they are a living testament to millennia of Indigenous stewardship and the profound impacts of colonialism. Place names like Cayuga Lake, Seneca Falls, and Onondaga County whisper tales of the Haudenosaunee presence, inviting us to look beyond the surface.

Understanding the Cayuga story compels us to acknowledge the true history of the land we stand on, to recognize the resilience of a people who have endured immense loss, and to appreciate their ongoing efforts to reclaim their heritage and future. As you visit New York’s beautiful landscapes, remember the invisible map of the Cayuga Nation – a map drawn by ancient footsteps, scarred by historical injustices, and now being redrawn with hope, determination, and an unwavering commitment to identity. It’s a powerful reminder that history is not just in books; it lives on in the land, in the people, and in the continuous journey towards justice and recognition. Engaging with this history enriches the travel experience, fostering a deeper respect for the Indigenous nations who are the original custodians of this remarkable land.