Beyond the Tourist Trail: Mapping Indigenous Food Systems in Bears Ears National Monument

For many of us, the concept of a map conjures images of neatly drawn lines, shaded topographical contours, and perhaps the ubiquitous blue dot on a digital screen guiding us to the nearest coffee shop. We use maps to navigate, to understand terrain, and to locate resources. But what if a map wasn’t just a static representation, but a living, breathing guide to sustenance, woven into the very fabric of culture, ceremony, and survival? What if it charted not just where food could be found, but how it connected generations, healed bodies, and sustained entire civilizations for millennia?

This profound understanding of "maps" – those intricate, traditional food systems of Native American peoples – is perhaps best experienced not in a museum, but by immersing oneself in a place where these systems are not only preserved but actively practiced. My journey took me deep into the heart of the American Southwest, to the breathtaking and culturally resonant landscapes of Bears Ears National Monument in southeastern Utah. This isn’t just a travel destination; it’s a living classroom, a repository of ancestral knowledge, and an unparalleled opportunity to witness how traditional food systems are, in essence, the most sophisticated and sustainable maps ever conceived.

The Unseen Maps: Beyond Cartography

Before delving into Bears Ears, it’s crucial to recalibrate our understanding of "maps" in an Indigenous context. For Native American communities, a map is rarely just a piece of paper. It’s a holistic understanding of the land, its cycles, its resources, and its spiritual significance. These maps are transmitted through oral histories, seasonal rounds, star knowledge, petroglyphs, ceremonies, and generations of direct observation and interaction with the environment. They dictate when to harvest, how much to take, where to hunt, and how to ensure the land’s continued bounty. They are dynamic, responsive, and intrinsically linked to stewardship and reciprocity.

Traditional food systems are the manifestation of these maps. They encompass the entire process from planting and harvesting to hunting, fishing, gathering, processing, and sharing. They are not merely about caloric intake but about cultural identity, community cohesion, spiritual well-being, and a deep respect for all living things. To understand these systems is to understand a people’s enduring connection to their homeland.

Bears Ears: A Living Tapestry of Sustenance

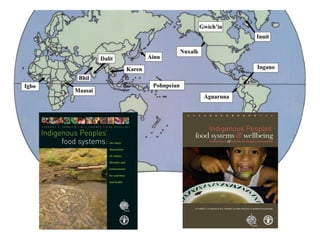

Bears Ears National Monument, a landscape of towering mesas, deep canyons, and ancient cliff dwellings, is a place of profound spiritual and cultural significance to numerous Indigenous nations, including the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe, Navajo Nation, Hopi Tribe, Ute Indian Tribe of the Uintah and Ouray Reservation, and Zuni Tribe. Its very designation as a national monument was a direct result of these tribes advocating for the protection of their ancestral lands, recognizing its irreplaceable value as a living cultural landscape.

Here, the concept of a traditional food system as a map becomes strikingly clear. The monumental landscape itself is etched with the narratives of sustenance. Every canyon, every mesa top, every spring, every pinyon grove tells a story of survival, innovation, and interconnectedness.

Mapping the Forager’s Bounty:

One of the most immediate "maps" revealed at Bears Ears is that of traditional foraging. For millennia, the Indigenous peoples of this region have expertly navigated the high desert environment, discerning edible from inedible, medicine from poison.

- Pinyon Nuts: The pinyon pine is perhaps the most iconic food source in the Bears Ears region. The knowledge of where and when to find the best pinyon groves, how to harvest the tiny, nutrient-dense nuts without damaging the trees, and the intricate process of roasting and storage, constitutes a complex seasonal map. A good "pinyon year" is a blessing, celebrated with communal gatherings that strengthen social bonds. To walk through a pinyon forest here, especially in late autumn, is to trace the footsteps of countless generations who relied on this precious resource.

- Juniper Berries: While often overlooked by outsiders, the small, bluish-purple juniper berry is another vital component of the traditional diet, used both for food and medicine. The "map" for juniper berries involves knowing which trees produce the sweetest, most resinous fruit, and how to process them for teas, flavoring, or even a form of flour.

- Prickly Pear Cactus: This resilient desert plant offers both fruit (tunas) and pads (nopales) that are rich in vitamins and minerals. The traditional map includes knowing the optimal time to harvest the fruit (after the spines have softened with frost), how to safely de-spine the pads, and various culinary preparations.

- Yucca and Agave: These plants, central to many desert Indigenous cultures, provided not just food (the stalks, flowers, and roasted hearts) but also fiber for tools, clothing, and shelter. The "map" for these plants involves a deep understanding of their growth cycles and sustainable harvesting practices that ensure their survival.

The Farmer’s Blueprint: Ancient Agricultural Maps:

While Bears Ears is often associated with foraging, it also holds the remnants of sophisticated agricultural systems developed by the Ancestral Puebloans and later practiced by other groups. The cliff dwellings and mesa top sites found throughout the monument are often accompanied by evidence of dry farming techniques that are astounding in their ingenuity.

- Terracing and Water Management: Along canyon walls and on mesa tops, one can observe subtle but deliberate modifications to the landscape – small check dams, terraces, and diversion channels. These are agricultural maps etched into the earth, designed to capture and retain precious rainwater, directing it to plots where drought-resistant corn, beans, and squash were cultivated.

- Seed Saving and Plant Knowledge: The "map" for these crops wasn’t just about where to plant, but what to plant. Traditional seed varieties, adapted over centuries to the harsh desert environment, are themselves a form of living map, carrying genetic information for resilience and nutritional value. Understanding soil types, sun exposure, and microclimates was paramount.

- The Three Sisters: Corn, beans, and squash, known as the "Three Sisters," are a prime example of a mapped, symbiotic agricultural system. Planted together, they support each other: corn provides a stalk for beans to climb, beans fix nitrogen in the soil for the corn, and squash leaves shade the soil, retaining moisture and deterring pests. This intercropping is a living map of ecological wisdom.

The Hunter’s Territory: Animal Pathways as Maps:

For many Indigenous communities, hunting was, and for some, remains, a vital part of the traditional food system. The "maps" here involve an intimate knowledge of animal behavior, migration patterns, habitat preferences, and the spiritual protocols surrounding the hunt.

- Deer and Elk: The canyons and forests of Bears Ears provide habitat for mule deer and elk. Traditional hunters would have known the best places for ambushes, the seasonal movements of herds between high and low elevations, and the signs of their presence. This knowledge, passed down through generations, is a dynamic map of the animal kingdom.

- Small Game: Rabbits, squirrels, and other small game were also important protein sources, requiring different hunting techniques and knowledge of their specific habitats and behaviors.

Experiencing the Map: A Responsible Traveler’s Guide

To truly appreciate Bears Ears as a map of Indigenous food systems, one must approach it with reverence and a willingness to learn.

- Seek Tribal-Led Experiences: The most authentic and respectful way to understand these traditional systems is through tours or programs offered by the sovereign tribes associated with Bears Ears. They can provide invaluable insights into the cultural significance of the landscape and its resources. Check with visitor centers or tribal cultural offices for opportunities.

- Visit Interpretive Centers: The Bears Ears Education Center (in Bluff) and other local museums (e.g., Edge of the Cedars State Park Museum in Blanding) offer exhibits that delve into the history and culture of the region’s Indigenous peoples, often showcasing traditional tools, food preparation techniques, and the importance of native plants.

- Hike with Purpose: When exploring the numerous trails and archaeological sites within Bears Ears, look beyond the scenic beauty. Observe the plants around you. Can you identify pinyon, juniper, prickly pear, yucca? Imagine how ancestral peoples would have utilized every aspect of their environment. Look for subtle signs of ancient agriculture – faint terraces, grinding stones, or storage areas. Remember to leave everything as you find it; never disturb archaeological sites or remove anything from the monument.

- Support Local Indigenous Businesses: If possible, seek out restaurants or markets in nearby communities (like Bluff or Blanding) that might feature traditional Indigenous ingredients or support Indigenous producers. This directly contributes to the economic well-being of the communities whose heritage you are experiencing.

- Practice Deep Respect and Leave No Trace: Bears Ears is a sacred landscape. Stay on marked trails, pack out everything you pack in, respect all cultural sites, and never climb on or enter cliff dwellings without proper guidance and permission. Understand that the land you are traversing is a living heritage, not just a backdrop for tourism.

The Deeper Meaning: Food Sovereignty and Cultural Resilience

Understanding traditional food systems in Bears Ears is not just an academic exercise; it’s a window into the ongoing struggles and triumphs of Indigenous peoples. The fight for the protection of Bears Ears was, at its heart, a fight for food sovereignty – the right of communities to define their own food systems, to grow, gather, hunt, and eat foods that are culturally appropriate, healthy, and sustainably produced.

These traditional food systems represent thousands of years of ecological wisdom, adapted and refined to thrive in often challenging environments. They embody resilience, sustainability, and a profound respect for the Earth. In a world increasingly disconnected from its food sources, places like Bears Ears serve as powerful reminders of what we have lost and what we can still learn.

Conclusion:

My journey through Bears Ears National Monument revealed that a map is far more than lines on paper. It is the intricate, living knowledge of the land itself – the seasonal rounds of foraging, the enduring legacy of ancient agriculture, the pathways of game, and the ceremonial practices that tie people to place. The traditional food systems of Native American peoples are these maps, guiding sustenance, culture, and spirit across generations.

To travel to Bears Ears with an open mind and a respectful heart is to embark on a journey that transcends mere sightseeing. It is an opportunity to learn from the original cartographers of this land, to understand the profound connection between people and place, and to witness the enduring power of food as the ultimate map of cultural identity and survival. It’s a travel experience that nourishes not just the body, but the soul, leaving you with a deeper appreciation for the land and the wisdom of those who have called it home for millennia.