Beyond the Lines: Navigating Bears Ears, A Living Map of Indigenous Land Issues

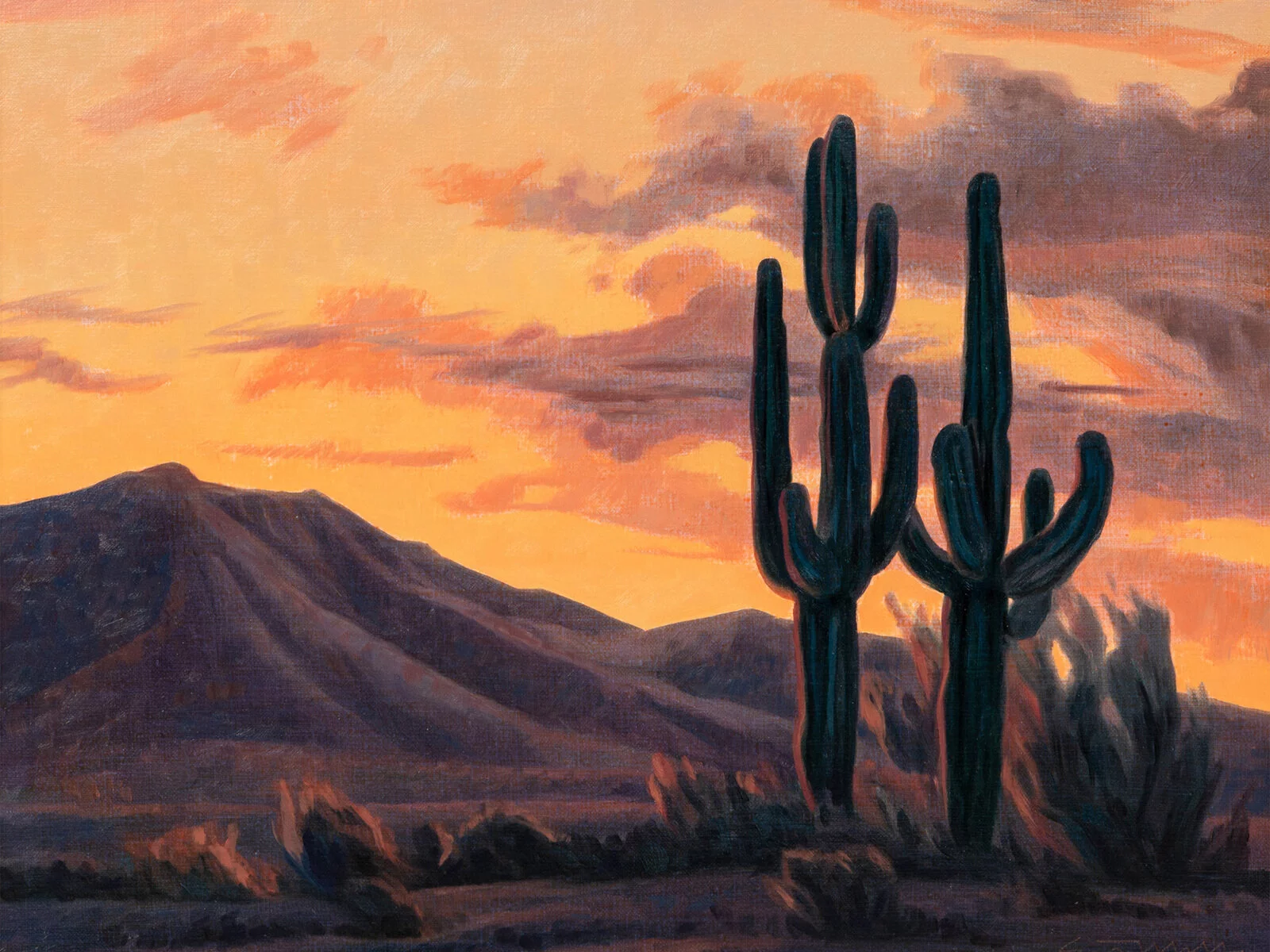

The American Southwest calls to travelers with its vast, untamed beauty – a landscape of colossal mesas, deep canyons, and an ancient silence that hums with history. But for those willing to look deeper than the scenic overlooks and Instagram-ready vistas, places like Bears Ears National Monument offer more than just a stunning view. They are living maps, etched not just with geological features but with layers of human experience, cultural memory, and the ongoing struggle for land sovereignty. This isn’t just a place to visit; it’s a place to understand, where the lines on a map represent battles fought, cultures preserved, and a future still being written.

Forget the simplistic maps you buy at a gas station, outlining highways and national park boundaries. To truly "review" Bears Ears, you must engage with a different kind of cartography – one drawn from millennia of Indigenous stewardship, oral histories, and a profound spiritual connection to the land. This is where the travel experience transcends mere sightseeing and becomes an education, an act of witnessing, and an opportunity for respectful engagement with contemporary land issues that are as old as the continent itself.

The Land as Sacred Text: What You See (And Don’t See)

From the moment you approach Bears Ears, whether from the north through the dramatic Manti-La Sal National Forest or the south via the arid expanses of San Juan County, Utah, the sheer scale is humbling. Two distinct twin buttes, known as Bears Ears (or "Hon’ne” by the Ute, “Shash Jáa” by the Navajo), rise majestically, serving as unmistakable landmarks. The monument encompasses a breathtaking mosaic of landscapes: towering red rock spires, deep slot canyons, pinyon-juniper forests, and high-altitude aspen groves.

As a traveler, your initial impression will likely be one of awe. You’ll find thousands of archaeological sites – cliff dwellings, kivas, petroglyphs, and pictographs – left by Ancestral Puebloan peoples and others over the last 12,000 years. Hiking through places like Grand Gulch or the Valley of the Gods, you walk amongst the ghosts of ancient civilizations, their presence palpable in the meticulously crafted stone structures clinging to canyon walls. These aren’t just ruins; they are libraries, repositories of knowledge, and sacred spaces.

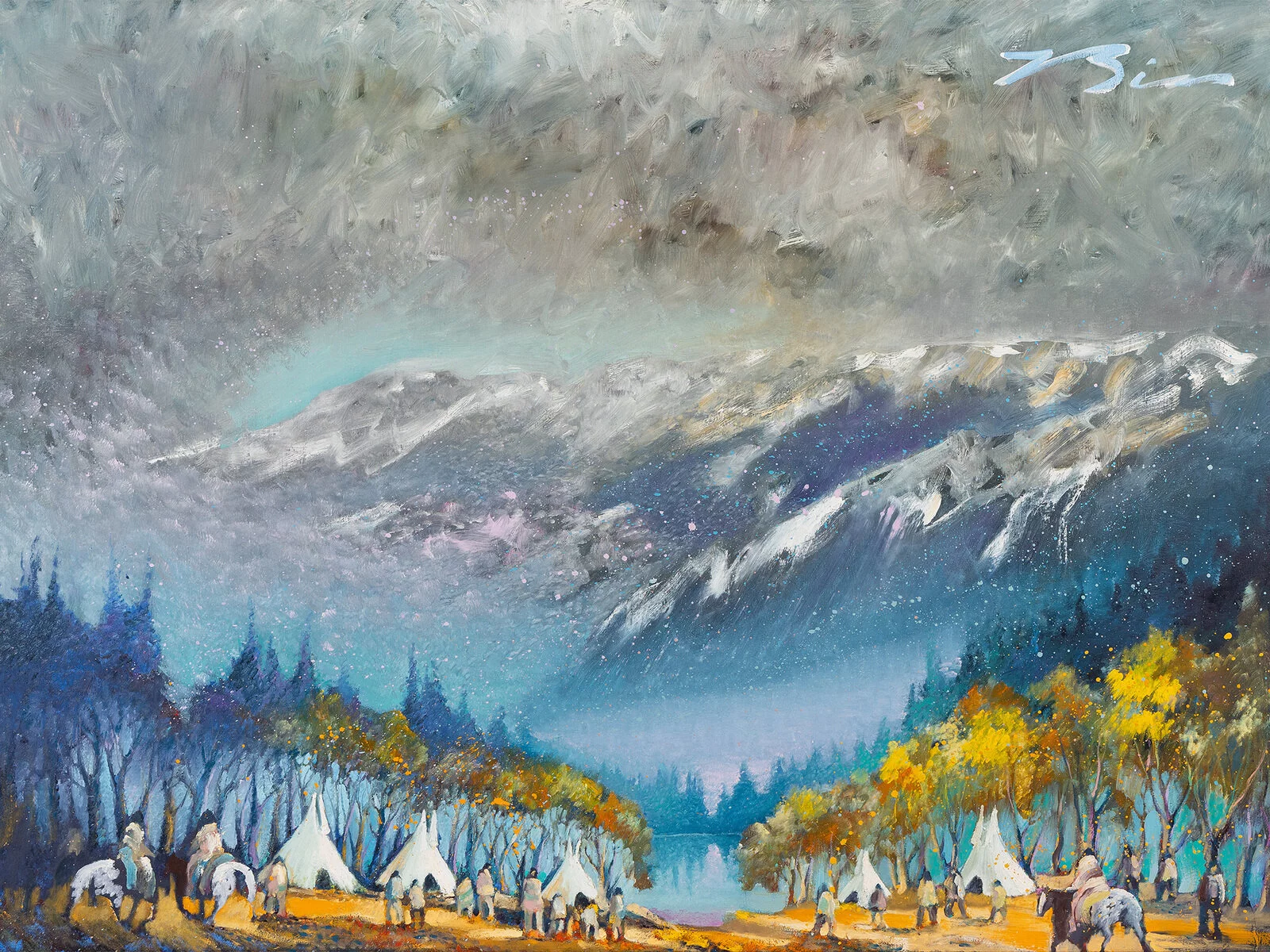

But what an Indigenous map reveals goes far beyond the archaeological. For the Ute Mountain Ute, Navajo, Hopi, Zuni, and Ute Indian Tribes (the Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition), this land is not merely an outdoor museum; it is home, a pharmacy, a ceremonial ground, and a spiritual sanctuary. Their maps aren’t lines on paper, but a deep, ingrained understanding of every spring, every plant, every game trail, and every sacred peak. These are maps of seasonal migrations, hunting grounds, gathering sites for medicinal herbs and ceremonial materials, and pilgrimage routes. They are maps of ancestral stories, songlines that navigate the landscape through generations of memory. When these tribes refer to Bears Ears as "a cultural landscape," they mean that every feature, every rock, every shadow holds meaning, history, and a piece of their identity. This profound connection is the bedrock upon which contemporary land issues are built.

The Clash of Cartographies: Lines of Power and Dispossession

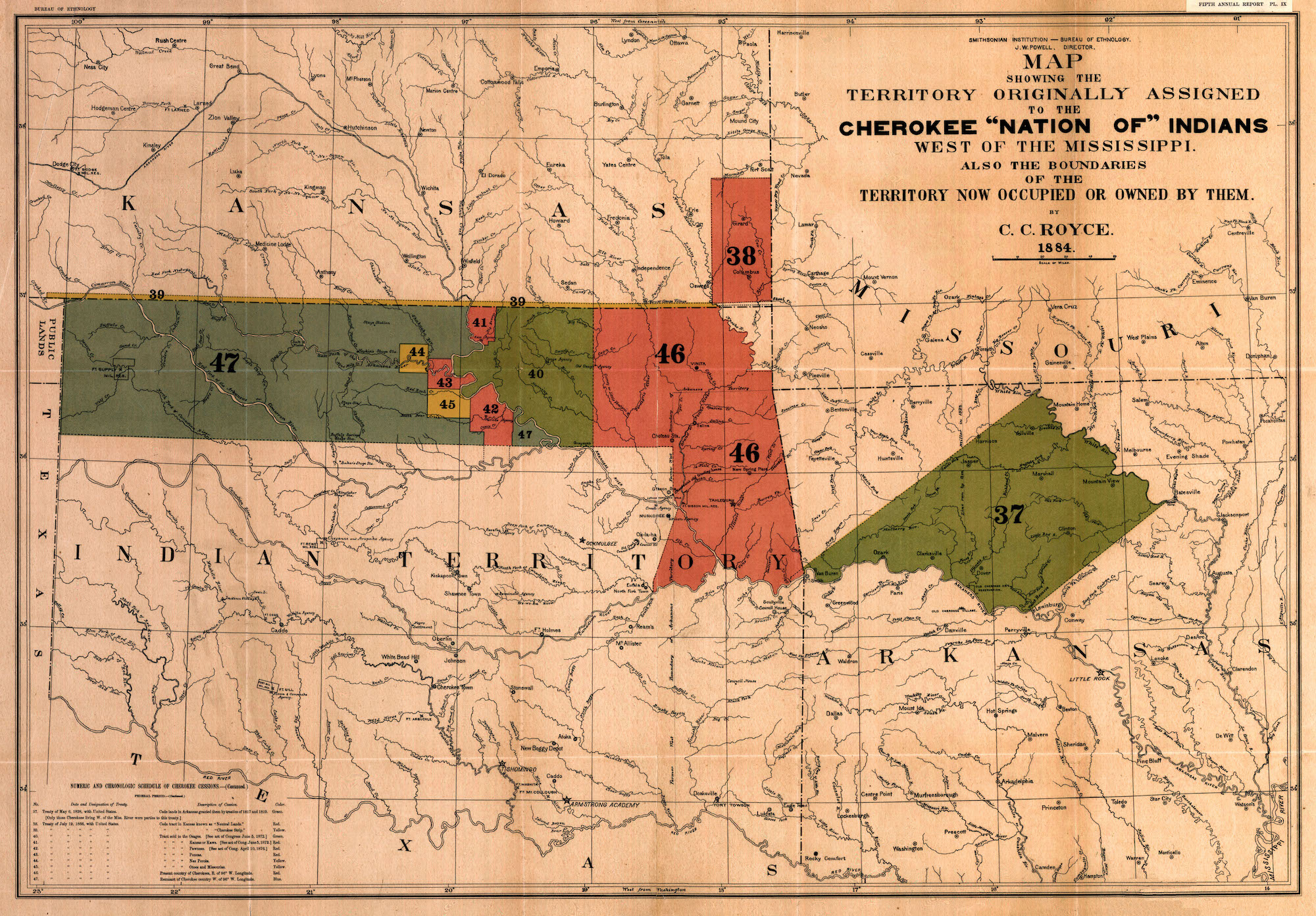

The "maps" of Indigenous peoples, rich with cultural and ecological knowledge, have historically been ignored or overwritten by colonial cartography. Western maps, with their grid lines, arbitrary borders, and property markers, were instruments of conquest and control. They defined "unclaimed" land, facilitating resource extraction and settlement, often disregarding the continuous presence and stewardship of Indigenous nations.

Bears Ears became a flashpoint in this clash of cartographies. For decades, the area was under federal management, but concerns grew over looting, desecration of sacred sites, and the threat of increased oil, gas, and uranium extraction. This prompted the five sovereign nations of the Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition to come together, unprecedented in its scope, to propose a new kind of map: a 1.9-million-acre national monument. Their proposal wasn’t just about conservation; it was about co-management, about recognizing their inherent sovereignty and their millennia-long role as stewards of this land.

In 2016, President Barack Obama designated the Bears Ears National Monument, a significant victory for Indigenous advocacy. This new map, drawn from Indigenous proposals, acknowledged the cultural and ecological significance of the region, protecting it from further degradation. But the lines on this map proved to be fluid, subject to political whims and competing interests.

Just a year later, President Donald Trump dramatically reduced the monument by 85%, shrinking it to two separate units totaling just over 200,000 acres. This was more than just a policy change; it was a physical redrawing of the map, effectively opening up vast swaths of culturally sensitive and ecologically vital land to potential mining, drilling, and other development. The message was clear: the priorities of resource extraction outweighed Indigenous claims and cultural preservation. This act of cartographic erasure sent shockwaves through Indigenous communities and conservation groups, highlighting the fragility of land protections and the ongoing struggle for recognition.

In 2021, President Joe Biden restored Bears Ears to its original 1.36 million acres (slightly less than Obama’s initial 1.9 million, but still a significant restoration). This too was a redrawing, an attempt to honor previous commitments and Indigenous sovereignty. But the back-and-forth nature of these designations underscores a critical contemporary land issue: the politicization of sacred landscapes and the constant battle to protect them from short-term economic gains.

The Modern Map as a Tool for Sovereignty

In the face of these challenges, Indigenous communities are increasingly leveraging modern mapping technologies, like Geographic Information Systems (GIS), alongside their traditional knowledge. This "counter-mapping" isn’t just about drawing new lines; it’s about asserting Indigenous narratives, documenting traditional ecological knowledge, and creating spatial data that supports their legal and political claims.

For instance, the Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition utilized sophisticated mapping to identify culturally significant areas, archaeological sites, and traditional use areas, creating a compelling visual argument for the monument’s protection. These maps are powerful tools in legal battles, legislative advocacy, and public education, translating complex cultural connections into data that Western legal and political systems can understand. They show not just where a site is, but why it matters, connecting tangible locations to intangible cultural heritage.

When you visit Bears Ears today, the ongoing land issues are not abstract concepts. They are visible in the landscape itself. You might see a mining claim stake on land that was once part of the monument, or a newly blazed trail through an area revered by Indigenous peoples. You see the debate playing out in the signs at visitor centers, in the conversations with locals, and in the very act of navigating a landscape whose boundaries have been so fiercely contested.

Your Journey: A Deeper Engagement

So, how does a traveler "review" a place like Bears Ears, knowing its fraught history and ongoing struggles? It means going beyond the superficial.

1. Prepare with Knowledge: Before you even set foot in the monument, read about its history. Learn about the five tribes of the Coalition. Understand the significance of the archaeological sites you might encounter. Websites like the Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition or Friends of Cedar Mesa are excellent resources.

2. Seek Indigenous Voices: Whenever possible, engage with local Indigenous communities. While there isn’t a dedicated tribal visitor center within the monument yet, nearby communities like Bluff, Blanding, and Mexican Hat offer museums, cultural centers, and local guides who can provide invaluable perspectives. The Edge of the Cedars State Park Museum in Blanding, for example, offers incredible insights into Ancestral Puebloan culture and contemporary Ute and Navajo life.

3. Practice Deep Respect: This cannot be overstated. You are visiting sacred land. Stay on marked trails. Do not touch or disturb archaeological sites, petroglyphs, or artifacts – "Take only pictures, leave only footprints" is the bare minimum. Respect privacy and cultural practices. Understand that many areas are considered sacred and are not simply tourist attractions.

4. Observe the Landscape Critically: Look for the signs of past and present human activity. Notice the variations in the landscape, the delicate ecosystems, and the evidence of ancient life. Consider how different "maps" – the federal monument boundaries, the traditional Indigenous use areas, the resource extraction claims – overlay and sometimes clash within this single territory.

5. Support Sustainable Tourism: Choose tour operators who prioritize ethical practices and respect Indigenous sovereignty. Support local businesses that demonstrate a commitment to the region’s cultural and environmental integrity.

Conclusion: Bears Ears as a Continuous Conversation

Bears Ears National Monument is more than just a travel destination; it is a profound lesson in the power of maps. It demonstrates how lines drawn on paper can dictate destinies, dispossess peoples, or, conversely, protect priceless heritage. It highlights the enduring resilience of Indigenous nations, who continue to fight for their lands, their cultures, and their right to self-determination.

A visit here is a call to reflection. It asks you to consider your own relationship to land, to history, and to the ongoing dialogues about justice and stewardship. By engaging with Bears Ears not just as a scenic wonder, but as a living map of contemporary land issues and Indigenous sovereignty, you transform your journey into something deeper. You become a participant in a continuous conversation, leaving with not just photographs, but with a richer understanding of a landscape that is as complex and contested as it is beautiful. This is a review of a place that challenges you to see beyond the surface, to understand that every line on every map tells a story – and sometimes, many conflicting stories – that continue to shape the world we inhabit.