Beyond the Lines: Experiencing the Living Map of Indigenous America in the Four Corners

Looking at a map of Native American tribal lands is one thing. It’s a static representation, lines drawn on paper, colors denoting territories that once were or still are. But to truly understand "who lived where"—and, crucially, who still lives where—requires stepping off the page and onto the land itself. It demands a journey into the heart of those ancestral and contemporary territories, allowing the landscape, the ruins, and the living cultures to tell their own stories.

For a travel experience that transcends mere sightseeing and transforms a historical map into a vibrant, three-dimensional narrative, there is no region more profound and impactful than the American Southwest, specifically the Four Corners area. This unique convergence of Utah, Colorado, Arizona, and New Mexico is not just a geographical marker; it is a profound cultural crossroads, a landscape etched with millennia of human history, and a testament to the enduring presence and resilience of indigenous peoples.

This isn’t a review of a single site, but rather an immersive travel concept—a journey designed to illuminate the very essence of "who lived where" by experiencing the diverse layers of indigenous occupation, innovation, and continuation. It’s about moving from the ancient cliff dwellings of the Ancestral Puebloans to the sprawling contemporary lands of the Navajo and the timeless mesas of the Hopi, witnessing the continuum of human connection to this powerful land.

The Ancestral Puebloans: Architects of Stone and Sky

Our journey begins by delving into the deep past, exploring the legacies of the Ancestral Puebloans (often referred to as Anasazi, though this term is now generally considered outdated by many). Their history here is a foundational layer on the indigenous map, revealing a sophisticated agrarian society that thrived in an often-harsh environment.

Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado:

Stepping into Mesa Verde is like walking into a living textbook of human adaptation. The sheer scale and ingenuity of the cliff dwellings—structures like Cliff Palace, Balcony House, and Spruce Tree House—are breathtaking. These aren’t just random caves; they are meticulously planned multi-story residential complexes, built directly into natural alcoves, offering protection from the elements and defense.

The experience of descending ladders and navigating through these ancient homes provides an intimate understanding of daily life here between 600 and 1300 CE. You see the small kivas (circular ceremonial chambers) that served as spiritual centers, the storage rooms for maize, beans, and squash, and the communal living spaces. The park’s well-preserved pithouses (earlier subterranean homes) and surface pueblos offer a chronological progression, demonstrating architectural evolution over centuries.

Mesa Verde teaches you that "who lived where" wasn’t static. These people moved, adapted, and innovated. Their departure from Mesa Verde around 1300 CE is still debated, but it’s widely believed they migrated south and east, becoming ancestors to modern Pueblo peoples in New Mexico and Arizona. This park is a powerful introduction to the concept of movement and change within the indigenous map.

Chaco Culture National Historical Park, New Mexico:

A stark contrast to Mesa Verde’s cliffside intimacy, Chaco Canyon presents a different, equally astounding facet of Ancestral Puebloan life. Here, between 850 and 1250 CE, a vast ceremonial, administrative, and economic center flourished, characterized by monumental "Great Houses" like Pueblo Bonito, Chetro Ketl, and Hungo Pavi. These aren’t just villages; they are colossal multi-story complexes, some with hundreds of rooms, meticulously aligned with celestial events, and connected by an elaborate network of ancient roads extending for hundreds of miles across the landscape.

Visiting Chaco is an experience of immense scale and profound silence. The desert wind whispers through the towering stone walls, inviting contemplation on the advanced knowledge of astronomy, engineering, and social organization required to build such a place. The sheer volume of timber, often sourced from distant mountains, and the precision of the masonry speak volumes about a highly organized society.

Chaco expands the "who lived where" narrative by showcasing a regional phenomenon—a complex cultural system that influenced vast territories, suggesting a level of interconnectedness far beyond what many might imagine from a simple map. It challenges the notion of isolated tribes, instead painting a picture of a vibrant, interactive indigenous world.

The Living Legacy: Navajo and Hopi Nations

Moving from the ruins of the past to the vibrant present is critical for understanding the full scope of "who lived where." The Four Corners is home to the largest tribal nation in the United States, the Navajo (Diné), and the deeply rooted communities of the Hopi. Their lands are not just historical sites; they are living, breathing territories where traditions endure and contemporary life thrives.

The Navajo Nation (Diné Bikeyah):

Spanning parts of Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah, the Navajo Nation is a land of breathtaking beauty and immense cultural significance. From the iconic red rock formations of Monument Valley to the sacred Canyon de Chelly, the landscape itself is woven into the fabric of Navajo identity and cosmology.

To experience the Navajo Nation is to engage with a living, resilient culture. Guided tours are essential here, often led by Navajo individuals who can share their perspective, history, and connection to the land. A tour into Canyon de Chelly, for example, reveals ancient Ancestral Puebloan ruins nestled against sheer cliffs, but also demonstrates how the Navajo have utilized and revered this same canyon for centuries, maintaining sheep herds and farms on the canyon floor.

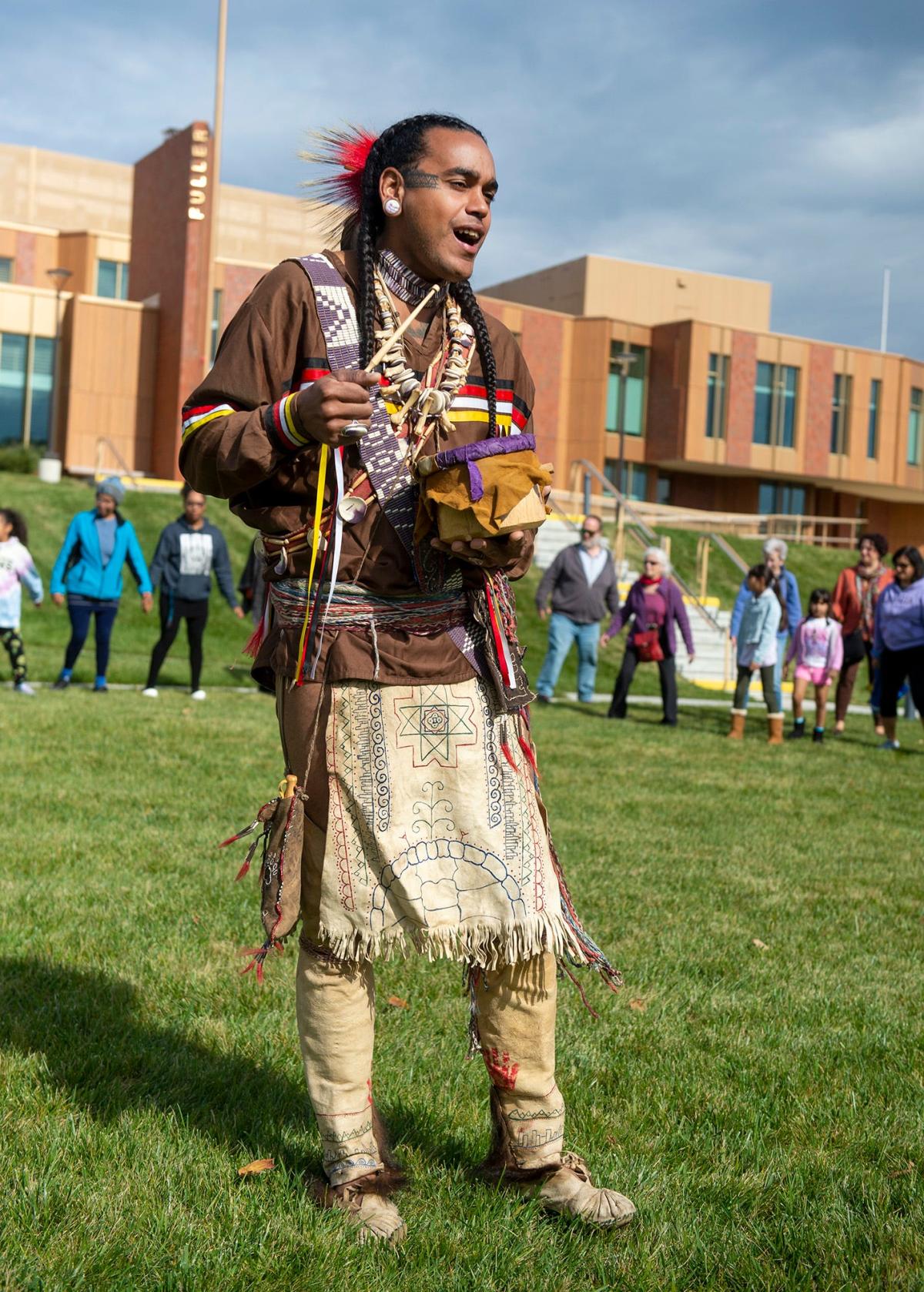

Beyond the famous landmarks, interaction with Navajo artists, weavers, and storytellers provides a deeper understanding of contemporary life. You learn about the importance of language (Diné bizaad), the clan system, and the concept of Hózhó (balance and harmony). The "who lived where" map here isn’t just about ancestral presence; it’s about continued stewardship, adaptation, and the ongoing struggle to maintain sovereignty and cultural identity in the modern world. It emphasizes that indigenous history is not confined to the past; it is a continuous, evolving story.

The Hopi Mesas, Arizona:

Perhaps the most profound living connection to the ancient past can be found on the Hopi Mesas. Perched atop three distinct mesa fingers, these villages are among the oldest continuously inhabited communities in North America, with some settlements like Old Oraibi dating back over a thousand years. The Hopi are direct descendants of the Ancestral Puebloans, and their spiritual and cultural practices remain deeply intertwined with their ancient heritage.

Visiting the Hopi Mesas is a privilege that demands the utmost respect and sensitivity. Tours are mandatory and must be arranged through official channels, led by authorized Hopi guides. Photography is often restricted or forbidden to protect the privacy and sacredness of their way of life.

The experience is less about grand archaeological sites and more about the profound sense of continuity. Walking through villages where stone homes have stood for centuries, witnessing the quiet rhythm of life, and hearing the stories of creation and stewardship from a Hopi guide, offers an unparalleled insight into a worldview deeply rooted in place. The "who lived where" here is a testament to unwavering cultural persistence, a spiritual connection to land that has been maintained through millennia, despite immense external pressures. It illustrates how traditional knowledge, ceremony, and community structure have allowed a people to thrive in their ancestral homeland.

The Deeper Meaning: Beyond the Map’s Lines

This journey through the Four Corners, tracing the footsteps of the Ancestral Puebloans, and walking alongside the Navajo and Hopi, does more than just fill in the blanks on a map. It transforms a flat, two-dimensional concept into a multi-layered, living experience.

- Understanding Movement and Adaptation: The map shows static lines, but the land reveals constant movement, migration, and ingenious adaptation to changing environments. It highlights how people responded to climate shifts, resource availability, and social dynamics.

- Challenging Stereotypes: It shatters monolithic views of "Native Americans." You witness the incredible diversity of cultures, languages, architectural styles, and spiritual practices that have thrived in this region.

- The Power of Place: Every ruin, every mesa, every canyon, tells a story of profound connection to the land. It’s a lesson in stewardship, not ownership—a concept deeply embedded in indigenous philosophies that stands in stark contrast to many modern approaches.

- Resilience and Continuation: Perhaps most importantly, this journey emphasizes that indigenous history is not just about the past. It’s about vibrant, living cultures that continue to thrive, innovate, and maintain their identities in the present. The map’s lines may denote historical territories, but the living communities demonstrate the ongoing presence and sovereignty of indigenous nations.

- Ethical Travel: This kind of immersive travel inherently requires a commitment to ethical engagement. Supporting local, indigenous-owned businesses, hiring tribal guides, respecting cultural protocols, and understanding the concept of tribal sovereignty are not just good practices; they are essential to enriching the experience and contributing positively to the communities you visit.

Practical Tips for the Engaged Traveler

To embark on this transformative journey, thoughtful planning is key:

- Time of Year: Spring and Fall offer the most pleasant weather. Summer can be intensely hot, and winter brings snow and road closures, especially at higher elevations or in remote areas.

- Transportation: A reliable vehicle with good ground clearance is highly recommended, especially for Chaco Canyon’s unpaved access roads and some areas within the Navajo Nation. Fuel stations can be sparse.

- Lodging: Book accommodations well in advance, especially near National Parks and within tribal lands. Consider staying at tribal-owned hotels or campgrounds where available.

- Guides are Essential: For places like Canyon de Chelly and the Hopi Mesas, authorized tribal guides are mandatory and provide invaluable insights. Support these local economies directly.

- Respect Tribal Sovereignty: Remember you are visiting sovereign nations. Laws and customs may differ from surrounding states. Observe all posted signs regarding photography, alcohol, and conduct. Always ask permission before photographing people.

- Leave No Trace: Practice strict Leave No Trace principles. Pack out everything you pack in. Do not disturb artifacts or natural features.

- Be Prepared: Carry plenty of water, snacks, sunscreen, and appropriate clothing for varying temperatures. Cell service can be non-existent in many areas.

- Support Local Economies: Purchase authentic arts and crafts directly from the artists. Eat at local, tribally-owned establishments.

This isn’t just a trip; it’s an education, a perspective shift, and a profound encounter with the enduring human spirit. By moving beyond the static lines of a map and engaging directly with the land and its peoples in the Four Corners, you gain an understanding of "who lived where" that is vibrant, complex, and utterly unforgettable. It’s a journey that leaves you not just with memories, but with a deeper appreciation for the rich tapestry of indigenous America, past and present.