Beyond the Horizon: Mapping Indigenous Architecture at the National Museum of the American Indian

For the intrepid traveler seeking to understand the intricate relationship between culture, land, and shelter, a journey to the National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI) in Washington D.C. offers an unparalleled experience. This isn’t just a museum; it’s a profound portal into the indigenous worldviews that shaped the diverse traditional housing types across North America, illuminated by the very maps – physical and conceptual – that guided their creation and habitation. Forget the typical museum fatigue; NMAI provides a direct, immersive dive into the ingenuity and spiritual depth of Native American architecture.

Upon entering the NMAI, the visitor is immediately struck by its unique architectural style, a curvilinear, buff-colored stone structure that evokes natural rock formations and ancient earthworks. This deliberate design sets the stage: this is a space built with and for indigenous perspectives, a stark contrast to many institutions that merely display indigenous artifacts. The exhibits on traditional housing and mapping are not static displays but living narratives, demonstrating how homes were not merely shelters but extensions of the land, cosmology, and social fabric of each nation.

Decoding Indigenous Maps: More Than Just Lines

Before delving into the specific housing types, it’s crucial to understand the indigenous concept of "map." Western cartography often prioritizes precise, fixed boundaries and topographical features, driven by resource extraction and political demarcation. Indigenous maps, as showcased at NMAI through various interpretations and historical artifacts, operate on a fundamentally different premise. They are often dynamic, mnemonic, and laden with cultural information.

These "maps" could be painted on hide, etched into stone, woven into textiles, or even recited as oral traditions passed down through generations. They detail not just physical landmarks but also spiritual sites, seasonal resource availability (hunting grounds, berry patches, fishing spots), migration routes, ceremonial paths, and the very stories that give meaning to a landscape. Crucially, these maps embody a deep ecological knowledge – understanding the flow of water, the prevailing winds, the soil composition, and the presence of specific building materials.

It is this profound, holistic mapping that directly informed the design and placement of traditional housing. A map showing the migratory path of bison dictated the use of mobile structures like tipis. A map indicating abundant cedar forests and salmon runs led to the development of monumental plank houses along the Northwest Coast. A map of arid desert mesas, complete with defensible positions and natural water sources, shaped the multi-story pueblos of the Southwest. The NMAI excels at presenting these conceptual maps, often juxtaposed with physical models and ethnographic accounts, allowing the visitor to grasp the profound connection between land knowledge and architectural innovation.

A Tapestry of Shelters: Housing Types and Their Stories

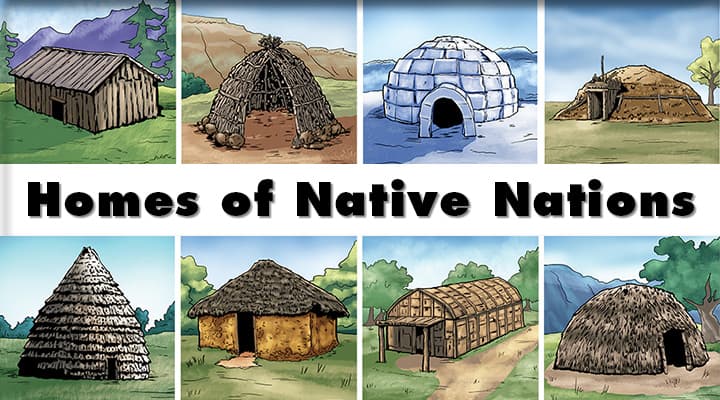

The NMAI’s exhibits offer a breathtaking survey of traditional Native American housing, each type a testament to human adaptability and cultural expression. They are not merely structures but reflections of diverse climates, available resources, spiritual beliefs, and societal organizations.

1. The Nomadic Adaptations: Tipis of the Plains

One of the most iconic images, the tipi, is brilliantly contextualized at NMAI. Far from being a primitive tent, the tipi (from the Lakota word típi, meaning "to dwell") was an engineering marvel perfectly suited for the nomadic lifestyle of the Plains nations like the Lakota, Cheyenne, and Crow. The exhibits explain how its conical shape, typically constructed from some 12-20 bison hides stretched over a framework of lodgepoles, was incredibly stable against strong winds. The smoke flaps at the top, adjustable with external poles, allowed for efficient ventilation for interior fires. Indigenous maps of the Plains would have highlighted vast grasslands, bison migration routes, and sources for lodgepoles (often found along river systems). The NMAI showcases not just the structure but the intricate paintings and symbolic decorations that transformed each tipi into a mobile canvas of family history and spiritual belief.

2. The Sedentary Communal Living: Longhouses of the Northeast

In stark contrast to the tipi are the longhouses of the Iroquois (Haudenosaunee) Confederacy and other Northeastern Woodlands nations. These impressive, elongated communal dwellings, constructed from a framework of saplings covered with bark (often elm or cedar), could stretch over 100 feet in length and house multiple related families. The NMAI exhibits emphasize the social and political significance of the longhouse, often referred to as "the People of the Longhouse" – a metaphor for their confederacy. Indigenous maps of the Northeast would have detailed dense forests, navigable rivers for trade and transport, and rich agricultural lands (corn, beans, squash – the "Three Sisters") that supported their sedentary lifestyle. The longhouse was not just a home but a political center, a spiritual space, and a hub of communal life.

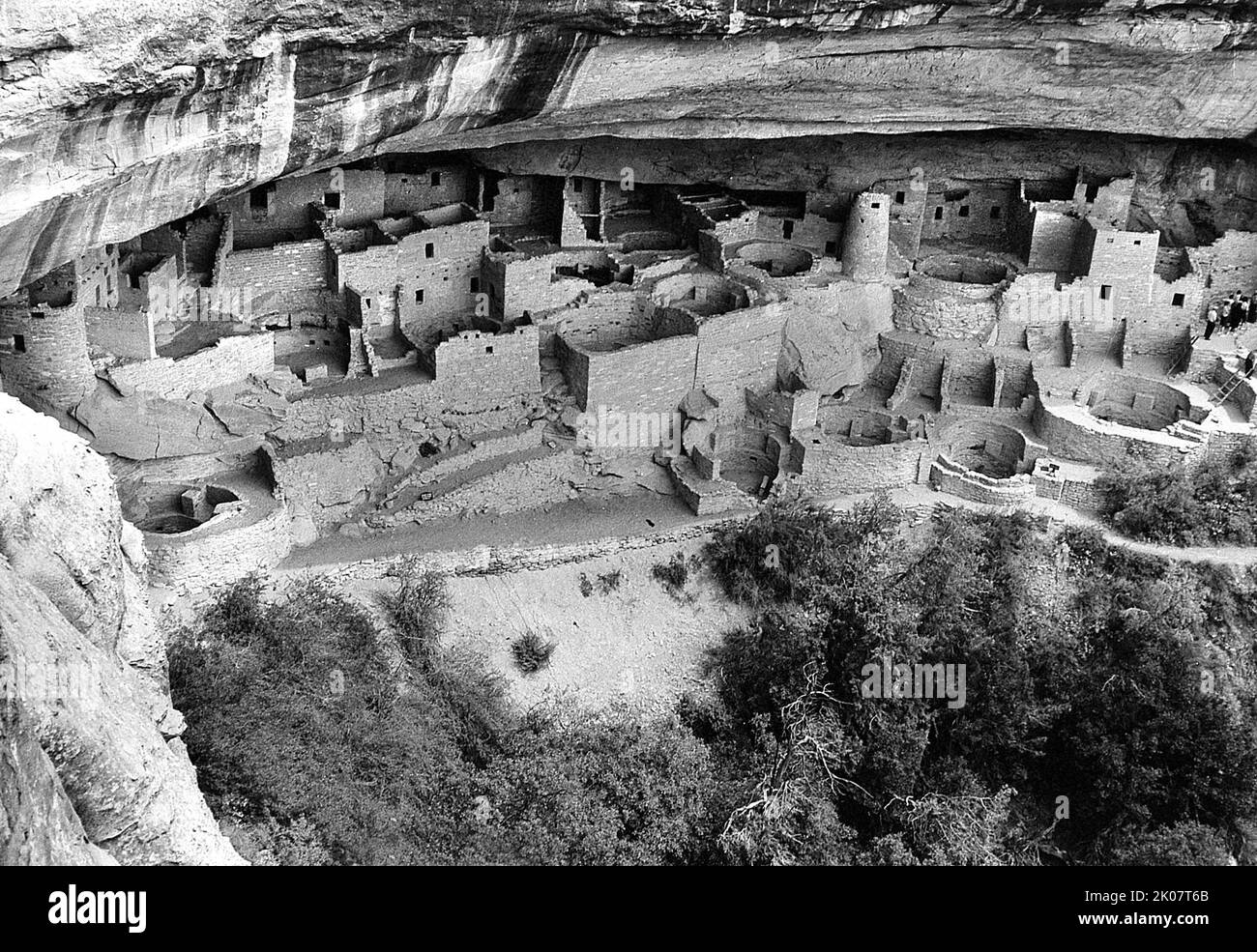

3. The Enduring Earth: Pueblos and Hogans of the Southwest

The arid Southwest demanded different architectural solutions, and the NMAI dedicates significant space to the ingenuity of the Pueblo peoples (Hopi, Zuni, Taos Pueblo) and the Navajo (Diné). The multi-story, apartment-like pueblos, constructed from adobe (sun-dried earth bricks) and stone, are remarkable for their thermal mass, keeping interiors cool in summer and warm in winter. Their defensive positions, often built into cliffs or atop mesas, reflect a deep understanding of the landscape’s strategic value, clearly delineated on indigenous maps.

The Navajo hogan, another iconic Southwest dwelling, is presented as a circular or polygonal earth lodge, typically constructed from logs and earth, with its door facing east to welcome the rising sun and good fortune. The hogan is deeply spiritual, representing the universe and a place for ceremonies and healing. Indigenous maps for the Diné would have included grazing lands for sheep, sources for juniper and piñon pine for construction, and sacred mountains that define their ancestral territory. The NMAI illustrates how these structures are not just buildings but living embodiments of spiritual and cultural identity.

4. The Monumental Woodworks: Plank Houses of the Northwest Coast

Moving to the lush, resource-rich Northwest Coast, the NMAI showcases the majestic plank houses of nations like the Haida, Kwakwaka’wakw, and Tlingit. Built from massive cedar planks and beams, these large, rectangular structures housed extended families and were often adorned with elaborate carved and painted totem poles. The sheer scale and craftsmanship speak volumes about the abundant resources (especially cedar) and the complex social structures that characterized these societies. Indigenous maps of this region would have detailed vast old-growth forests, salmon-rich rivers, and coastal territories, indicating where these monumental resources could be harvested and where communities thrived. The plank house was a symbol of wealth, status, and ceremonial life.

5. The Ingenious Adaptations: Chickees and Earth Lodges

The NMAI further broadens the perspective with examples like the Seminole chickee of the Florida Everglades – open-sided, thatched-roof structures on raised platforms, perfectly adapted to a hot, humid, and often flooded environment. Or the earth lodges of the Mandan and Hidatsa along the Missouri River, semi-subterranean dome-shaped homes that offered insulation against harsh winters and hot summers, often mapped alongside fertile river bottomlands. Each structure, meticulously detailed in the exhibits, tells a story of intimate connection to a specific environment, a story often embedded within the indigenous maps of those regions.

The Interplay: Maps, Environment, and Culture in Architecture

What the NMAI articulates so powerfully is that traditional Native American housing was never a standalone architectural endeavor. It was, and remains, an integral part of a comprehensive indigenous worldview. The maps – whether physical, oral, or spiritual – provided the blueprint for understanding the land’s offerings and challenges. The environment dictated the available materials and climatic necessities. The culture, with its social structures, spiritual beliefs, and ceremonial practices, shaped the form, orientation, and symbolism of the dwelling.

The museum’s curated experience allows visitors to see how a nation’s knowledge of its water sources, hunting grounds, sacred sites, and even the direction of prevailing winds, directly informed where and how they built their homes. These weren’t just buildings; they were living entities, often seen as metaphors for the cosmos, embodying the relationship between humans and the natural world. NMAI’s focus on the indigenous voice ensures that these stories are told with authenticity and respect, moving beyond simplistic ethnographic descriptions to convey the profound ingenuity and spiritual depth embedded in every traditional structure.

Beyond the Exhibit: What Travelers Gain

Visiting the National Museum of the American Indian is more than just observing artifacts; it’s an educational journey that reshapes one’s understanding of architecture, land, and culture. Travelers leave with a far deeper appreciation for:

- Indigenous Ingenuity: The sheer brilliance of engineering and material science demonstrated by diverse Native American housing types, developed without the tools and technologies of modern construction.

- Ecological Wisdom: The profound, centuries-old understanding of local environments and sustainable living that guided every aspect of home building and community planning.

- Cultural Diversity: A vivid realization of the vast differences between Native American nations, each with its unique adaptations, beliefs, and architectural expressions.

- The Power of Place: How traditional homes were not just shelters but sacred spaces, embodying a nation’s identity, history, and spiritual connection to their land.

- Challenging Narratives: The NMAI directly counters many stereotypes about Native American peoples, showcasing their resilience, innovation, and rich cultural heritage.

For any traveler with an interest in sustainable architecture, cultural studies, or simply a desire to deepen their understanding of North America’s foundational peoples, the National Museum of the American Indian is an essential destination. It offers a direct, unflinching, and awe-inspiring look at how Native American maps – in all their forms – charted not just territories, but the very blueprints for living in harmony with the land, expressed through an extraordinary tapestry of traditional housing types. Go, explore, and let your perceptions of "home" be forever expanded.