Bears Ears: A Journey Through America’s Living Indigenous Map of Land, Culture, and Contention

The American Southwest, with its boundless horizons, crimson canyons, and stoic mesas, often evokes images of pristine wilderness and ancient mysteries. For many travelers, it’s a landscape of escape, a backdrop for adventure. But beneath the surface of this breathtaking beauty, especially in places like southeastern Utah, lies a complex and deeply contested story of land, sovereignty, and survival. This is the story of Bears Ears National Monument, a place that isn’t just a geological wonder, but a living, breathing map of contemporary Indigenous land disputes, etched not in ink, but in rock, spirit, and relentless advocacy.

Forget your conventional travel guide’s focus on amenities or star ratings. To "review" Bears Ears is to engage with something far more profound: it’s to understand how Indigenous peoples are literally redrawing the map of America, asserting their ancestral claims through a powerful fusion of traditional knowledge and modern activism. My journey through Bears Ears wasn’t just a scenic drive; it was an immersion into a landscape where every mesa, every canyon, every ancient dwelling tells a story of Indigenous mapping that directly shaped its designation, its reduction, and its eventual restoration.

The Landscape: A Postcard Hiding Millennia

First, let’s acknowledge the obvious: Bears Ears is stunning. Named for the two distinctive, twin buttes that rise dramatically from the landscape, resembling a bear’s ears peering over the horizon, this region of southeastern Utah is a geological marvel. Imagine vast expanses of sagebrush and juniper giving way to deep canyons carved by ancient rivers, towering sandstone cliffs painted in hues of ochre and rust, and secret alcoves sheltering Ancestral Puebloan cliff dwellings that cling precariously to rock faces.

For the casual traveler, it offers unparalleled opportunities for hiking, rock climbing, stargazing, and photography. The silence is profound, broken only by the whisper of wind or the distant cry of a hawk. Driving along the Moki Dugway, a dizzying unpaved switchback road carved into the face of a cliff, offers panoramic views that stretch to the distant Abajo Mountains. Discovering a hidden petroglyph panel or a well-preserved kiva can feel like stepping back in time, a tangible connection to the people who thrived here thousands of years ago.

This raw, untamed beauty is precisely what draws visitors. But to truly experience Bears Ears, one must look beyond the surface, recognizing that every vista, every rock formation, every archaeological site is not just a point of interest, but a node on a deeply personal, Indigenous map.

Indigenous Maps: More Than Lines on Paper

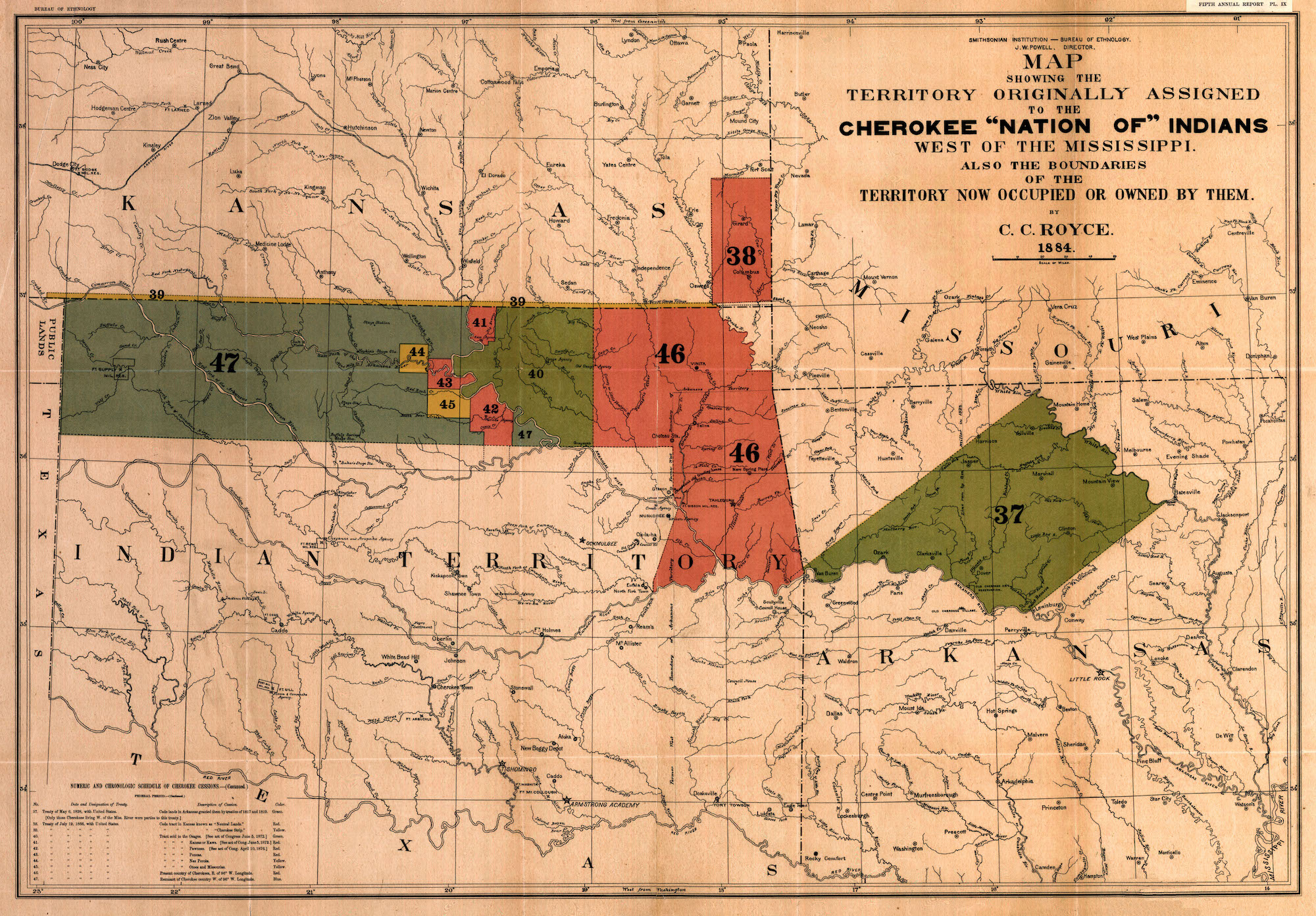

The conventional Western map is a cartographic exercise in defining boundaries, ownership, and resources – lines drawn on paper, often imposed from above. But for the Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition (comprising the Navajo Nation, Hopi Tribe, Ute Mountain Ute Tribe, Ute Indian Tribe of the Uintah and Ouray Reservation, and Zuni Tribe), their maps of Bears Ears are entirely different. These are not static documents; they are living narratives, deeply interwoven with oral histories, sacred ceremonies, traditional plant gathering areas, hunting grounds, ancestral trails, and countless named places in Indigenous languages.

When the idea of protecting Bears Ears began to gain momentum in the early 2010s, Indigenous communities didn’t just advocate; they mapped. They produced detailed, layered maps that depicted not just archaeological sites (which are plentiful, with over 100,000 documented sites in the region), but entire cultural landscapes. These maps meticulously charted:

- Sacred Sites: Places of spiritual significance, ceremonial use, and ancient prayer.

- Traditional Use Areas: Locations for gathering medicinal plants, edible plants, basketry materials, and firewood.

- Hunting and Fishing Grounds: Areas vital for subsistence and cultural practices.

- Travel Corridors: Ancient trails and migration routes connecting communities over millennia.

- Place Names: Thousands of Indigenous names for mountains, rivers, springs, and canyons, each carrying its own story and historical context.

These weren’t just academic exercises; they were powerful legal and political tools. They demonstrated an unbroken, continuous connection to the land, a deep stewardship that predates any colonial claim. They showed that this was not merely "wilderness" waiting to be discovered or developed, but a vibrant, living cultural landscape, actively used and cared for by multiple sovereign nations.

The Arc of Contention: Designation, Reduction, Restoration

The story of Bears Ears as a national monument is a microcosm of the larger struggle for Indigenous land rights and sovereignty in the United States.

The Obama Designation (2016): A Victory for Indigenous Cartography

After years of tireless advocacy, extensive mapping, and direct engagement with federal officials, the Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition achieved a monumental victory. In December 2016, President Barack Obama, utilizing the Antiquities Act of 1906, designated 1.35 million acres as Bears Ears National Monument. Critically, the proclamation explicitly acknowledged the unique cultural importance of the region to Indigenous peoples and established a groundbreaking co-management structure, giving the Inter-Tribal Coalition a direct voice in the monument’s management. This was a direct testament to the power of their maps, which provided irrefutable evidence of the land’s profound Indigenous significance.

The Trump Reduction (2017): A Disregard for Indigenous Voices

Just ten months later, the rug was pulled out from under this historic achievement. In December 2017, President Donald Trump drastically reduced the monument by 85%, shrinking it to a mere 200,000 acres, ostensibly to "reverse federal overreach" and allow for more resource extraction. This move was widely condemned by Indigenous nations, conservation groups, and even some archaeologists. It was perceived as a direct affront to Indigenous sovereignty and a blatant disregard for the ancestral maps and cultural connections that had underpinned the original designation. The reduction not only opened up sacred sites and culturally significant areas to potential development and looting but also sent a chilling message about the fragility of Indigenous land protections.

The Biden Restoration (2021): A Renewed Hope

The fight, however, was far from over. Indigenous nations, supported by environmental groups, immediately launched legal challenges. In October 2021, President Joe Biden, after extensive consultation with tribal leaders, restored the monument to its original 1.35 million-acre boundaries. This restoration was another landmark moment, reaffirming the importance of Indigenous voices in land management and acknowledging the cultural and historical significance of the entire landscape. It reinforced the principle that the land, as mapped and understood by its original inhabitants, deserved protection.

The Ongoing Review: What You Experience Today

Visiting Bears Ears today is to experience this arc of contention firsthand. While the monument is officially restored, the scars of the past reduction and the ongoing threats of extractive industries, inadequate funding, and rising tourism are palpable.

- The Power of Place: As you hike to an ancient cliff dwelling or stand atop a mesa overlooking vast stretches of red rock, you’re not just seeing beautiful scenery. You’re standing on land that was fought for, protected by maps drawn from generations of knowledge, then threatened, and ultimately, saved. This awareness adds an incredible layer of meaning to every step.

- The Co-Management Model: While still in its early stages and facing funding challenges, the Bears Ears Commission—comprised of representatives from the five coalition tribes—is actively involved in managing the monument alongside federal agencies. This innovative approach to land stewardship is revolutionary, attempting to integrate traditional ecological knowledge with Western scientific management. As a visitor, you might not directly interact with the commission, but knowing its existence changes your perception of "public land" from solely federal oversight to a shared responsibility with sovereign nations.

- Educational Opportunities: Rangers and interpretive signs often highlight the Indigenous connection, but to truly understand, you must seek out Indigenous perspectives. Engage with local tribal members, visit cultural centers in nearby towns like Bluff or Blanding, or read books and articles written by Indigenous authors about the region. This is where the "review" deepens – it’s not just about the landscape, but the narratives that define it.

- Responsible Tourism: The very act of visiting Bears Ears comes with a responsibility. The increased recognition and restoration bring more visitors, which can inadvertently lead to damage to sensitive cultural sites. Practicing "Leave No Trace" principles is paramount. Even more, it means traveling with respect, understanding that you are a guest on ancestral lands, and educating yourself about the ongoing struggles and triumphs of the Indigenous peoples who call this place home.

Bears Ears: A Blueprint for the Future

Bears Ears is more than just a national monument; it’s a testament to the enduring power of Indigenous mapping and advocacy in shaping contemporary land policy. It demonstrates that maps are not just tools for navigation or demarcation; they are potent instruments of cultural memory, political assertion, and spiritual connection. The disputes surrounding Bears Ears are not isolated incidents; they reflect broader conflicts playing out across the American West and indeed, the world, where Indigenous communities are fighting for self-determination, environmental justice, and the protection of their ancestral lands from extractive industries and colonial legacies.

For the traveler seeking more than just a pretty view, Bears Ears offers a profound experience. It invites you to transcend the typical tourist gaze and engage with a landscape that is simultaneously ancient and fiercely contemporary. It challenges preconceived notions of "wilderness" and "public land," revealing them as deeply human and culturally inscribed spaces.

To "review" Bears Ears is to acknowledge its breathtaking beauty, yes, but more importantly, it is to bear witness to the resilience of Indigenous cultures, the transformative power of their maps, and the ongoing struggle to protect sacred lands. It is to leave not just with stunning photographs, but with a deeper understanding of how the fight for land, sovereignty, and cultural survival continues to shape the very fabric of America. This isn’t just a place to visit; it’s a place to learn, to reflect, and to understand the profound truth that the land itself, when mapped by its original stewards, is a powerful advocate for justice.