The Unseen Stories: Navigating the Aleut People’s Historical Lands Map of Alaska

A map is never just a collection of lines, colors, and place names. For Indigenous peoples, particularly the Aleut (Unangan) people of Alaska, a historical lands map is a vibrant tapestry woven from millennia of intimate connection, profound identity, and a history marked by both resilience and immense struggle. This article delves into the Aleut people’s historical lands map of Alaska, revealing not just geography, but the deep historical, cultural, and spiritual narratives embedded within their ancestral domain. Suitable for the discerning traveler and history enthusiast, this exploration seeks to illuminate the enduring spirit of the Unangan people.

The Aleutian Arc: A Homeland Forged by Fire and Sea

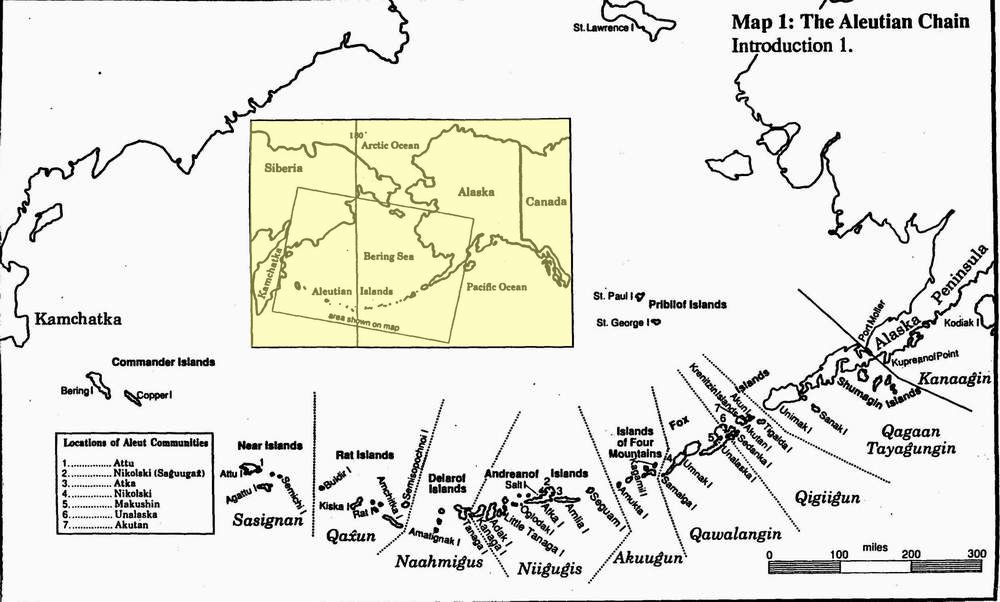

To understand the Aleut historical lands map, one must first grasp the extraordinary geography of their homeland. The map primarily depicts the Aleutian Archipelago, a 1,100-mile chain of over 300 volcanic islands stretching westward from the Alaska Peninsula into the Bering Sea, almost reaching Russia’s Kamchatka Peninsula. This is not merely a borderland; it is a world unto itself – a place where the North Pacific meets the Bering Sea, where fog, fierce winds, and active volcanoes shape an environment of both unforgiving challenge and unparalleled abundance.

The Unangan people, meaning "People of the East" or "Coastal People," have inhabited this arc for at least 9,000 years. Their traditional territory extends beyond the immediate islands to include the western tip of the Alaska Peninsula and the Pribilof Islands, crucial seasonal hunting grounds in the Bering Sea. Critically, some Aleut communities also reside on the Commander Islands in Russia, a testament to historical movements and the enduring cultural ties across what is now an international boundary.

Looking at this map, one immediately recognizes the distinct, linear sweep of the islands. For the Unangan, these aren’t isolated dots but a continuous highway – the sea itself. Their mastery of maritime navigation, boat-building, and hunting allowed them to thrive in this seemingly harsh environment, demonstrating an ingenious adaptation to a vast, interconnected ecosystem. The map, therefore, is not just land; it’s the sea, the currents, the hunting grounds, and the pathways that defined their existence.

Pre-Contact Flourishing: A Sophisticated Maritime Culture

Before the arrival of Europeans, the Aleutian chain supported a thriving, highly sophisticated culture. Archaeological evidence across the map’s expanse reveals a complex society with advanced technologies, intricate social structures, and a rich spiritual life. The Unangan were masters of the sea, their very existence predicated on their profound understanding of marine mammals.

Their iconic vessel, the baidarka (or iqyax in Unangam Tunuu, the Aleut language), was a marvel of engineering. These sleek, fast kayaks, made of sea mammal skins stretched over a wooden or bone frame, allowed single, double, or triple hunters to navigate treacherous waters, pursuing seals, sea otters, sea lions, and even whales. The map, in its quiet depiction of these islands, implicitly celebrates the routes taken by these magnificent boats, the hunting territories carefully observed, and the resource-rich waters that sustained entire communities.

Villages were strategically located along the coastlines, offering access to fresh water, sheltered bays, and optimal hunting grounds. Their homes, called barabaras (or ulax), were semi-subterranean sod houses, expertly designed to withstand the region’s intense winds and cold. Their diet was almost entirely marine-based, supplemented by birds, eggs, and sparse tundra plants. This sustainable way of life, honed over millennia, demonstrated an unparalleled harmony with their environment – a balance that the historical map implicitly underscores as the bedrock of their identity.

The Cataclysm of Contact: Russian Colonization and the Fur Rush

The quiet narrative of the pre-contact map was shattered with the arrival of Vitus Bering’s expedition in 1741, ushering in an era of profound and often brutal transformation. Russian promyshlenniki (fur traders and hunters) quickly followed, drawn by the incredible abundance of sea otters, whose pelts were highly prized in global markets. The Aleutian chain, as depicted on the map, became the epicenter of Russia’s colonial expansion into North America.

This period, from the mid-18th century through the Alaska Purchase in 1867, was catastrophic for the Unangan people. The promyshlenniki forced Aleut men into labor, compelling them to hunt sea otters for Russian profit, often under threat of violence against their families. Disease, particularly smallpox and measles, to which the Unangan had no immunity, decimated populations. Within a century, the Unangan population plummeted by an estimated 80-90%.

The map of this era tells a story of displacement, forced relocation, and the introduction of foreign settlements. Traditional hunting grounds were exploited to near exhaustion. Some Unangan were forcibly moved to the Commander Islands to establish new hunting colonies, explaining the presence of Aleut communities there to this day. The historical lands map, in this context, becomes a somber record of territorial infringement and the violent disruption of an ancient way of life. Yet, even amidst this devastation, the Unangan maintained their identity, adapting and resisting in various forms, a testament to their deep roots in this land.

American Rule and the World War II Betrayal

With the Alaska Purchase in 1867, the Aleutian Islands and the Unangan people came under American jurisdiction. While the overt violence of the Russian fur trade largely subsided, new forms of assimilation and marginalization emerged. American commercial interests continued to exploit marine resources, often to the detriment of Unangan subsistence. Policies like the establishment of boarding schools aimed to suppress Indigenous languages and cultures, further eroding traditional practices and knowledge passed down through generations. The map now represented a territory under a new colonial power, with its Indigenous inhabitants largely overlooked or actively suppressed.

However, one of the most tragic and least-known chapters in American history unfolded on the Aleutian map during World War II. After the Japanese invaded Attu and Kiska, two westernmost Aleutian Islands, in June 1942, the U.S. government, fearing further invasion, forcibly evacuated nearly all remaining Unangan civilians from the western and central Aleutian Islands and the Pribilofs. They were taken to internment camps in Southeast Alaska, far from their homes, often in abandoned canneries and mines with deplorable conditions.

This act was an unfathomable betrayal. While Japanese Americans were interned, the Aleuts, American citizens, were interned not because of disloyalty, but because they were the people of the Aleutians. They lost their homes, their belongings, and many suffered from disease and neglect in the camps. A significant portion of the evacuated population perished. When they were finally allowed to return after the war, many of their villages were in ruins, looted, or destroyed by American forces who had occupied them. Attu, once a vibrant Unangan village, was never re-inhabited, becoming a ghost island on the map – a stark reminder of the war’s devastating impact on Indigenous communities. The map, in this period, speaks of absence, displacement, and a profound sense of loss.

Resilience and Reclaiming Identity: The Map as a Symbol of Revival

Despite centuries of exploitation, disease, and forced displacement, the Unangan people have demonstrated extraordinary resilience. The latter half of the 20th century saw a powerful resurgence of Indigenous rights movements in Alaska, culminating in the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA) of 1971. This landmark legislation established regional and village corporations, granting Alaska Natives land ownership and financial resources in exchange for extinguishing aboriginal land claims.

For the Aleut people, ANCSA resulted in the creation of The Aleut Corporation (a regional corporation) and numerous village corporations across their historical lands. While not a return to traditional governance, ANCSA provided a new framework for economic self-determination and cultural preservation. The historical lands map now gained new significance, representing not just ancestral connection but also a tangible, albeit complex, form of modern land ownership and stewardship.

Today, cultural revitalization efforts are vibrant. Unangam Tunuu, once suppressed, is being taught in schools and community programs, ensuring its survival. Traditional arts, such as basket weaving, carving, and the intricate construction of replica baidarkas, are experiencing a revival. Organizations like the Aleutian/Pribilof Islands Association work tirelessly to advocate for Unangan rights, promote cultural heritage, and address contemporary challenges facing their communities. The map, once a record of loss, is now a symbol of renewed identity, self-determination, and the enduring spirit of a people deeply connected to their ancestral waters and lands.

The Living Map: Identity in the 21st Century

For the Unangan people, their historical lands map is not merely a static representation of the past; it is a living document that defines their identity in the 21st century. It embodies their traditional ecological knowledge (TEK), passed down through generations, which is crucial for understanding and managing the delicate ecosystems of the Aleutian arc. As climate change increasingly impacts the Arctic and Subarctic regions, with rising sea levels, ocean acidification, and shifting marine life, the Unangan people are on the front lines, their traditional knowledge offering invaluable insights into adaptation and mitigation.

The map also highlights contemporary challenges and aspirations. Economic development, often tied to fishing, shipping, and even military presence, must be carefully balanced with the preservation of cultural sites and traditional subsistence practices. The vastness of their ancestral territory, as seen on the map, underscores the immense responsibility and ongoing effort required to protect their unique heritage against external pressures.

For the traveler and history enthusiast, understanding the Aleut historical lands map offers a profound lesson. It’s an invitation to look beyond the exotic landscape and see the thousands of years of human story etched into its contours. It encourages a deeper appreciation for the resilience of Indigenous cultures and the complex, often painful, history that shapes modern Alaska. Visiting these lands, whether virtually or in person, with the context of this map in mind, transforms a geographical journey into a historical and cultural immersion – a journey into the heart of the Unangan people.

Conclusion: An Enduring Legacy

The Aleut people’s historical lands map of Alaska is far more than a geographical reference. It is a powerful narrative of survival, adaptation, and an unwavering spiritual connection to one of the planet’s most dramatic and resource-rich environments. From the ingenuity of their pre-contact maritime culture to the devastating impacts of colonization and war, and ultimately to their vibrant efforts at cultural revival and self-determination, the Unangan people’s journey is a testament to the enduring human spirit.

For those who seek to understand Alaska beyond its picturesque surface, this map serves as a crucial guide. It reminds us that every line, every island, and every stretch of sea holds stories of profound historical significance and deep-seated identity. To engage with this map is to engage with the Unangan people themselves – a people whose history is as vast and as compelling as the Aleutian chain they call home. It urges us to listen, to learn, and to respect the enduring legacy of the Unangan, ensuring their stories continue to be told for generations to come.