Beyond the Lines: Exploring Native American Land Management & Traditional Maps at the Indian Pueblo Cultural Center

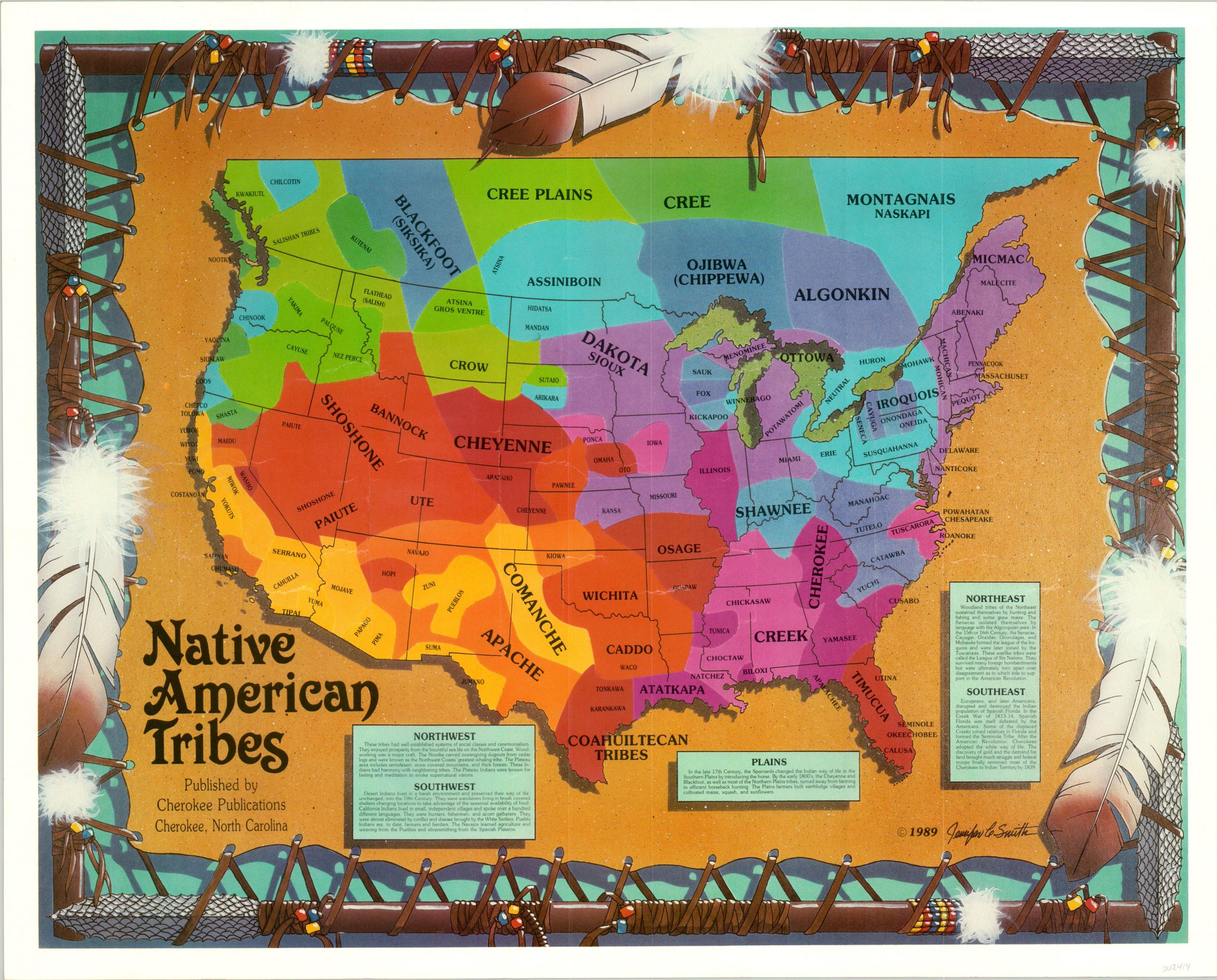

Forget everything you think you know about maps. For centuries, Western cartography has defined land by lines, borders, and grids – a two-dimensional representation of ownership and control. But step into the world of Native American traditional land management, and you quickly learn that a map isn’t just paper and ink; it’s a living, breathing knowledge system woven into the very fabric of existence. It’s a song, a ceremony, a migration route, a sacred site, a generational story, and an intricate understanding of the land’s heartbeat.

My recent visit to the Indian Pueblo Cultural Center (IPCC) in Albuquerque, New Mexico, wasn’t just a cultural excursion; it was a profound re-education. This review isn’t about the pristine condition of the exhibits (though they are excellent) or the efficiency of the gift shop (also great). It’s about how the IPCC, as a vital cultural institution, serves as an unparalleled gateway to understanding the deep, complex, and often overlooked legacy of Native American maps of traditional land management – a wisdom that holds critical lessons for our modern world.

The IPCC: A Living Repository of Indigenous Wisdom

From the moment you approach the IPCC, with its stunning Pueblo architecture reflecting the sun-drenched landscape, you sense a deep connection to the earth. This isn’t just a museum; it’s a dynamic cultural hub owned and operated by the 19 Pueblos of New Mexico. Its mission is to preserve and perpetuate Pueblo culture, and in doing so, it naturally becomes a powerful interpreter of Indigenous land management.

The center’s layout, designed to evoke a traditional Pueblo village, immediately grounds you in the environment. Exhibits are not just static displays; they are storytelling platforms that reveal the intricate relationship between the Pueblo peoples and their ancestral lands. You’ll see pottery etched with symbols representing water, corn, and mountains; textiles woven with patterns that map out spiritual journeys; and historical photographs depicting daily life intricately tied to the changing seasons and available resources. Each artifact, each image, each narrative piece contributes to a larger, holistic "map" of how these communities have understood, navigated, and sustained their environments for millennia.

Beyond Cartography: The True Nature of Native American "Maps"

The IPCC masterfully challenges the conventional definition of a map. Here, a map is not a static document but a dynamic, multi-layered system of knowledge passed down through generations.

-

Oral Histories and Songs: The exhibits emphasize that stories, songs, and ceremonies are perhaps the most potent forms of Indigenous mapping. They encode vital information about migratory routes, sacred places, resource locations (water sources, hunting grounds, foraging areas), historical events, and environmental changes. A song might describe a journey across a desert, naming every landmark, waterhole, and potential danger. A story might recount the origin of a mountain, imbuing it with spiritual significance that dictates respectful interaction. At the IPCC, listening to recorded narratives and reading interpretive panels, you begin to grasp how these oral traditions serve as GPS, ecological surveys, and legal documents all rolled into one.

-

Petroglyphs and Geoglyphs: The center highlights examples of ancient rock art found across the Southwest. These aren’t just art; many are sophisticated territorial markers, astronomical calendars, seasonal indicators, and records of resource availability. A series of spirals might denote the passage of time or the path of the sun, crucial for planting and harvesting cycles. Animal figures could indicate important hunting grounds or migration paths. The IPCC provides context for these ancient "maps," helping visitors understand their functional as well as artistic significance.

-

Material Culture: Pottery, weaving, and jewelry often contain symbols that represent elements of the landscape – rain clouds, lightning, mountains, rivers, corn, squash, beans. These symbols are not merely decorative; they are visual representations of a spiritual and practical connection to the land. A pottery design depicting a specific rain pattern could be a prayer for water, but also a visual reminder of the importance of water conservation and the knowledge of where and when rain typically falls.

-

Mental Maps and Experiential Knowledge: The most profound form of Indigenous mapping is the internal, experiential map held by individuals and communities. This map is built through direct interaction with the land over a lifetime: knowing the subtle changes in elevation, the types of soil in different areas, the behavior of local wildlife, the cycles of plants, the direction of winds, and the taste of different waters. The IPCC’s focus on intergenerational knowledge transfer underscores how this deep, embodied understanding of place is continuously taught and reinforced, forming the foundation of effective land management.

Traditional Land Management: A Blueprint for Sustainability

The core of the IPCC’s educational impact lies in its ability to articulate the principles and practices of traditional Native American land management. This isn’t about simply extracting resources; it’s about a reciprocal relationship where humans are stewards, not masters, of the land.

-

Reciprocity and Stewardship: A recurring theme is reciprocity – the understanding that if you take from the land, you must also give back. This manifests in ceremonies, prayers, and sustainable practices. Exhibits explain how harvests are never exhaustive, always leaving enough for the land to regenerate and for other species to thrive. Stewardship means taking responsibility for the health of the entire ecosystem, not just the parts that directly benefit humans. The IPCC illustrates this through narratives of respectful hunting practices, selective gathering, and ceremonies that express gratitude to the earth.

-

Water Management: In the arid Southwest, water is life. The Pueblo peoples developed ingenious water management systems centuries before modern engineering. The IPCC showcases the history and principles of acequias (community-managed irrigation canals) and waffle gardens (sunken gardens designed to trap and conserve moisture). These systems are not just practical; they are social structures that foster community cooperation and shared responsibility, reflecting a collective "map" of water flow and allocation.

-

Fire Management: While often controversial in modern contexts, traditional Indigenous fire management is gaining renewed recognition. Many Native American communities historically used controlled burns to clear underbrush, promote new growth, enhance biodiversity, and prevent catastrophic wildfires. The IPCC’s exhibits, particularly those discussing historical ecological practices, allude to this sophisticated understanding of fire as a tool for maintaining healthy landscapes, a deliberate act of management informed by centuries of observation and knowledge.

-

Polyculture and Biodiversity: The concept of the "Three Sisters" – corn, beans, and squash planted together – is a prime example of Indigenous agricultural wisdom. Corn provides a stalk for beans to climb, beans fix nitrogen in the soil, and squash leaves shade the ground, retaining moisture and deterring pests. This isn’t just efficient farming; it’s an ecological strategy that promotes soil health, reduces erosion, and increases biodiversity, forming a micro-ecosystem within the larger landscape. The IPCC beautifully illustrates this through diagrams and descriptions, connecting it to the broader principles of ecological balance.

-

Seasonal Calendars and Cycles: Traditional life was intricately linked to the seasons. Planting, harvesting, hunting, gathering, and ceremonial cycles were all dictated by the sun, moon, and stars. These seasonal "maps" ensured that resources were utilized at their peak, minimizing waste and ensuring long-term availability. The IPCC’s exhibits often feature calendars and astronomical knowledge, demonstrating how celestial observations guided land use decisions.

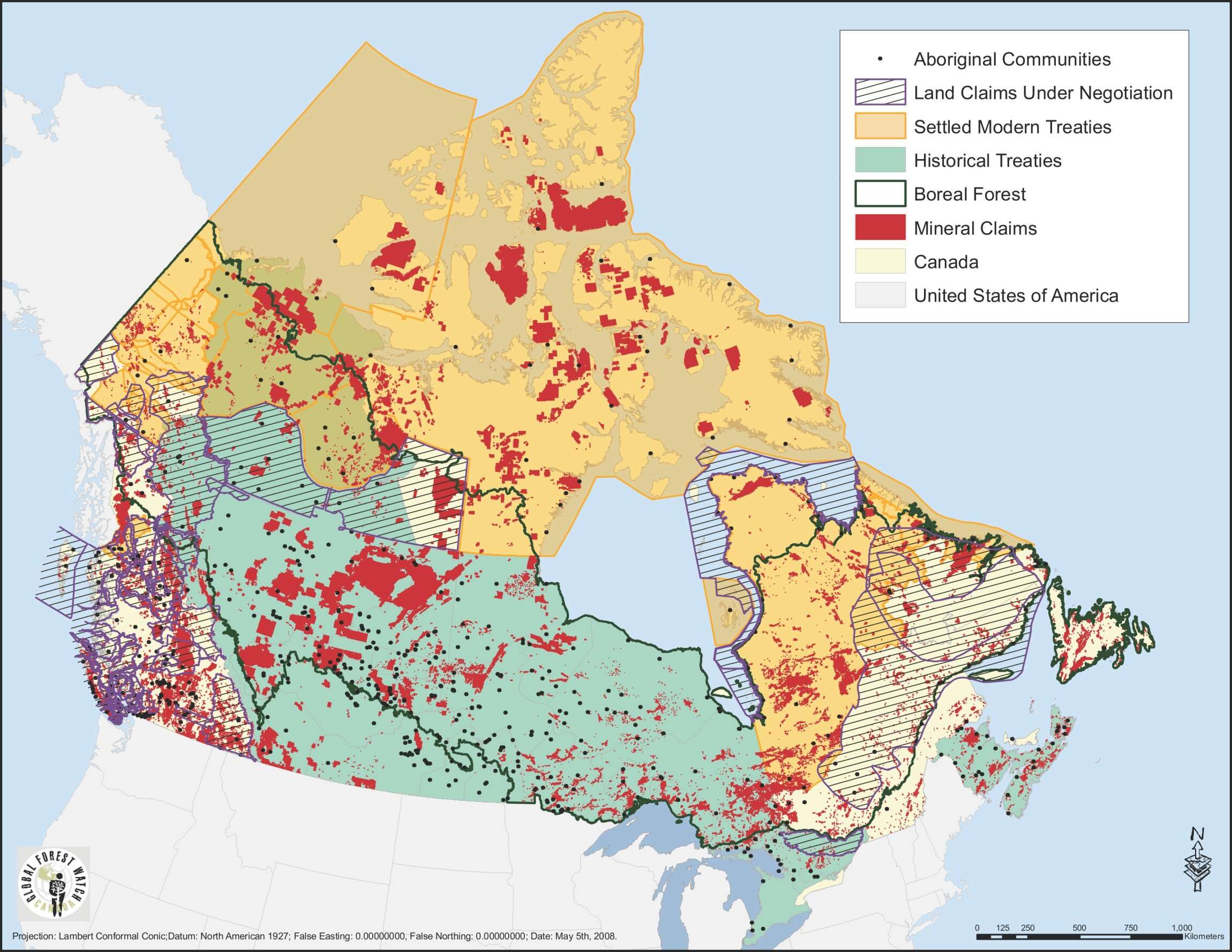

Modern Relevance and the Call for Re-learning

Perhaps the most compelling aspect of the IPCC experience is its profound relevance to contemporary challenges. As we grapple with climate change, biodiversity loss, and resource depletion, the ancient wisdom preserved and presented here offers crucial insights.

The center subtly but powerfully advocates for the integration of Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) into modern land management practices. Discussions around co-management of national parks and forests, the re-adoption of Indigenous fire practices, and the renewed interest in sustainable agriculture all echo the principles showcased at the IPCC. Visiting here, you realize that these aren’t just historical curiosities; they are blueprints for a more sustainable future. The "maps" of Indigenous knowledge are not outdated; they are timeless.

Practicalities for the Traveler:

Visiting the Indian Pueblo Cultural Center is an enriching experience for anyone interested in Native American culture, history, and the environment.

- Time: Allocate at least 3-4 hours to fully explore the exhibits, watch the cultural dances (often performed on weekends), and browse the excellent gift shop and art galleries.

- Food: The Pueblo Harvest Cafe offers delicious Indigenous-inspired cuisine, providing another layer of cultural immersion. Their traditional Pueblo bread is a must-try.

- Engagement: Don’t be afraid to ask questions of the knowledgeable staff and interpreters. Their insights deepen the understanding of the exhibits.

- Beyond IPCC: Use the IPCC as a springboard. It provides a fantastic overview, but respectfully visiting specific Pueblos (check their websites for visitor protocols) or exploring sites like Chaco Culture National Historical Park (with an understanding of its Ancestral Puebloan context) will further enrich your journey.

Conclusion: A Shift in Perspective

My time at the Indian Pueblo Cultural Center was transformative. It didn’t just review a location; it reviewed my understanding of the land itself. It laid bare the limitations of Western cartography and unveiled the profound, holistic "maps" of Native American traditional land management – systems built on reciprocity, deep ecological knowledge, and an unwavering respect for the earth.

The IPCC isn’t just a place to learn about history; it’s a place to learn how to see the world differently. It teaches us that true sustainability comes not from drawing lines on a map, but from understanding the intricate, interconnected web of life that flourishes within those perceived boundaries, and recognizing our sacred role as stewards of that living map. It’s a journey beyond the lines, into the heart of the land.