Beyond the Lines: Navigating America’s True Cartography of Land and Loss

Forget the glossy tourist maps, the neatly drawn state lines, and the highways that promise effortless transit. To truly understand the land you travel across in North America, you must look deeper, to a cartography far more profound and painful: the Native American maps of land cessions and appropriations. These aren’t just historical documents; they are a living testament to sovereignty lost, cultures reshaped, and a resilience that continues to define Indigenous nations today. This is not a review of a single location, but an immersive journey into the very concept of "place" as defined and redefined by these powerful, often heartbreaking, maps.

Imagine standing on a bluff overlooking a river, perhaps the Mississippi, the Ohio, or a tributary flowing through the Appalachian foothills. Your modern map shows you a state park, a national forest, or a small town. But if you could overlay the Indigenous maps of just a few centuries ago, you would see a vibrant tapestry of tribal territories, hunting grounds, sacred sites, and established communities – the ancestral homelands of nations like the Cherokee, Choctaw, Muscogee (Creek), Lakota, Nez Perce, and countless others. These were not empty wildernesses awaiting "discovery," but complex, managed landscapes, intrinsically tied to the identities of their stewards.

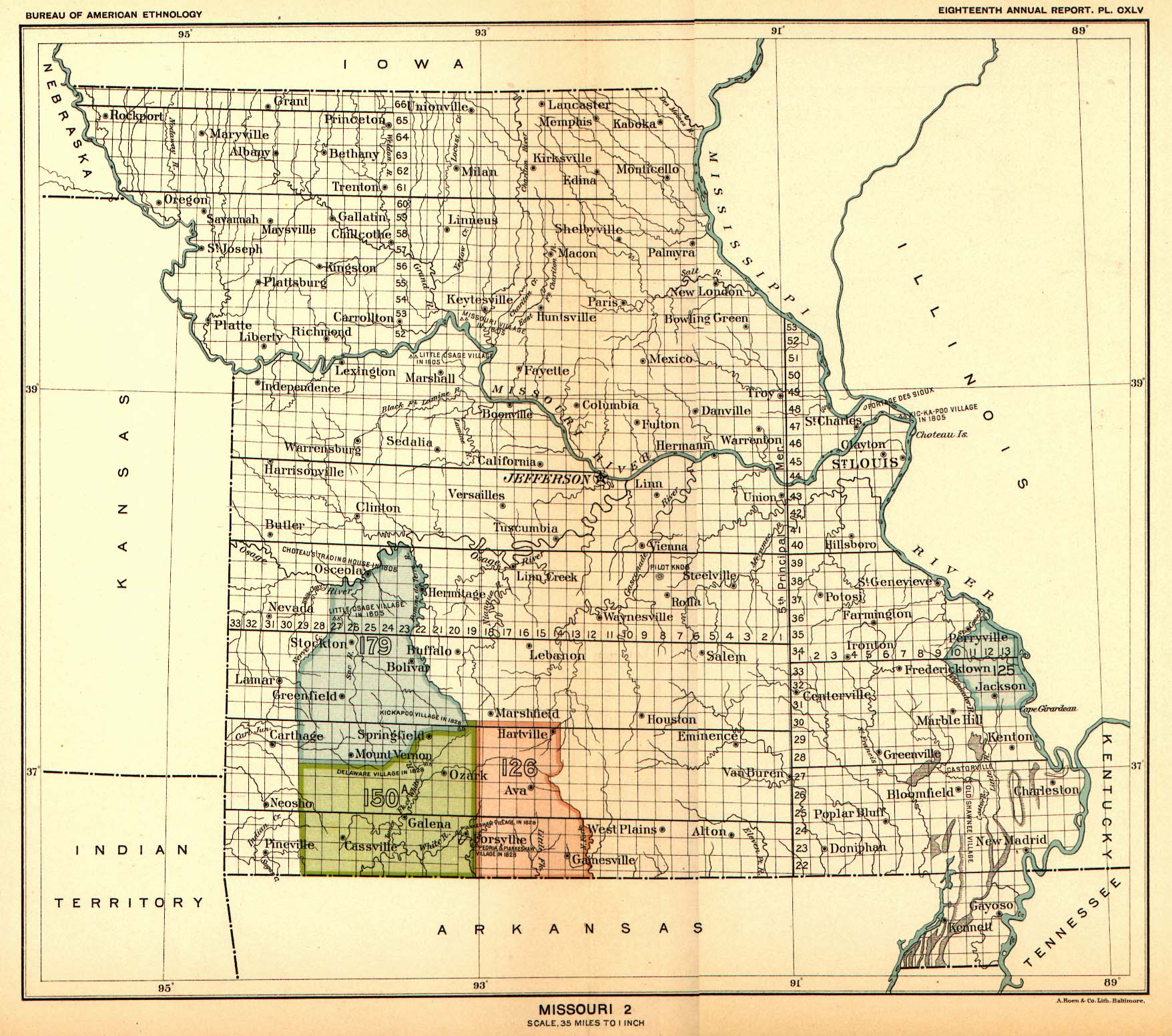

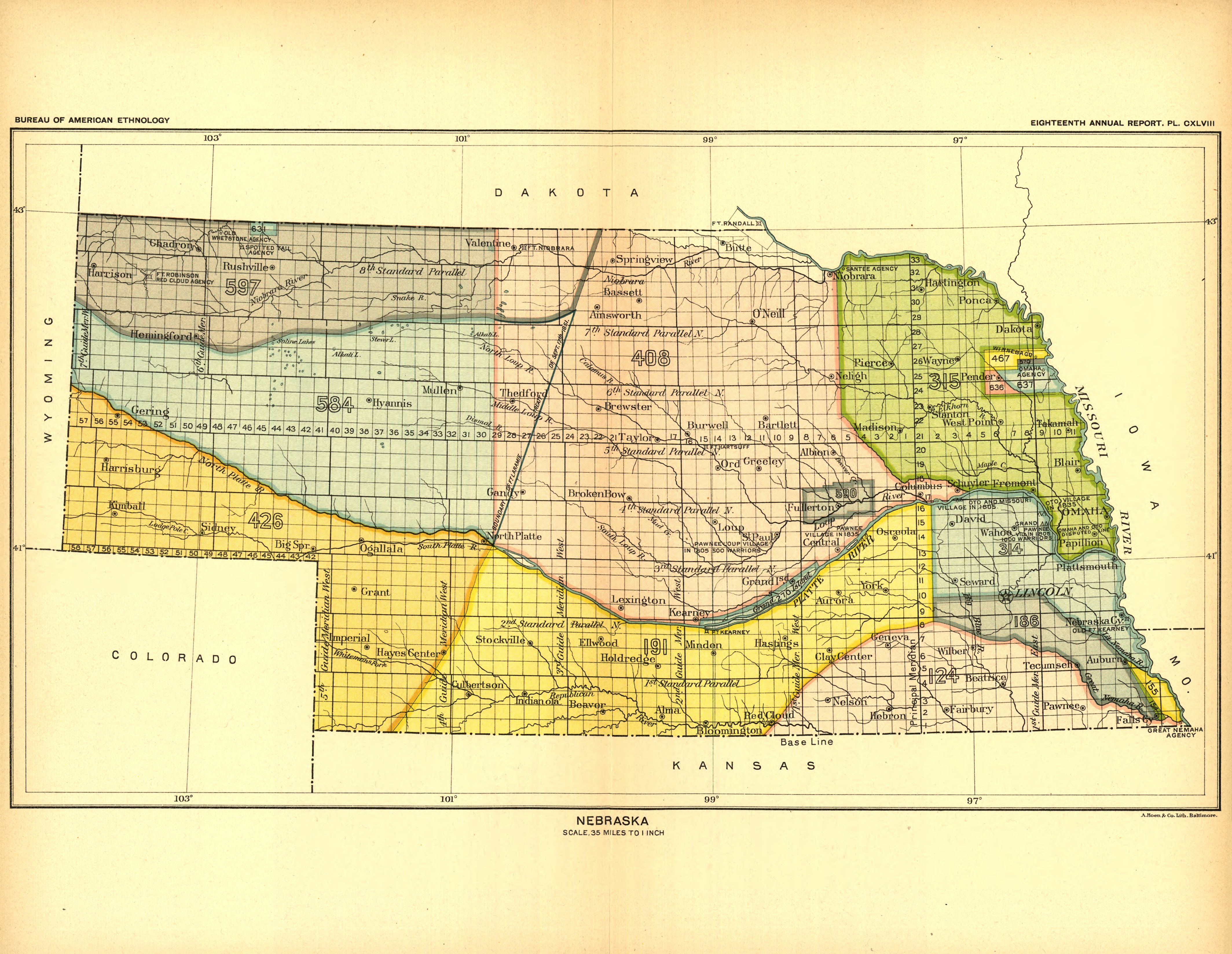

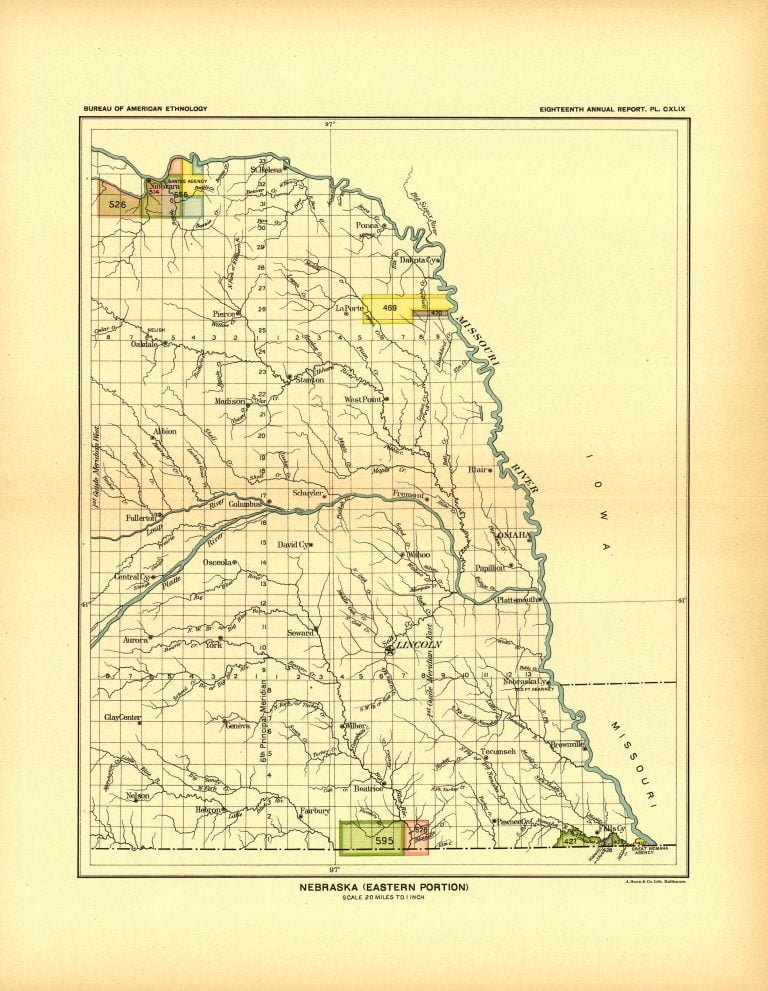

The maps of land cessions tell the story of how these Indigenous nations were systematically dispossessed. "Cession" – the formal yielding of territory by one state or government to another – sounds neutral, even voluntary. The reality for Native Americans was anything but. These were often treaties signed under immense duress, economic pressure, military threat, or by unrepresentative factions of a tribe, later disavowed by the majority. Each line drawn on these maps represents not just a boundary shift, but a profound rupture: the loss of sacred sites, burial grounds, crucial agricultural lands, hunting territories, and the very foundation of communal life.

The Southeastern Crucible: A Journey Through Removal

To truly grasp this cartographic tragedy, let’s focus our journey on the southeastern United United States, a region often romanticized for its Southern charm, but whose landscape is etched with the scars of the Indian Removal Era. This is where the story of land cession reaches one of its most brutal apexes, culminating in the Trail of Tears.

The "Five Civilized Tribes" and the Erosion of Sovereignty:

Prior to the 19th century, nations like the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Muscogee (Creek), and Seminole occupied vast, rich territories across what is now Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Florida, Tennessee, and North Carolina. They were not nomadic bands; they were settled agricultural societies with sophisticated governance, written languages (in the case of the Cherokee), and established economies. Their maps, though often oral or woven into textiles and pottery, defined their world.

Then came the treaties. From the late 1700s through the 1830s, a relentless series of agreements chipped away at their lands. Early treaties, like the Treaty of Hopewell (1785) with the Cherokee, initially sought to define boundaries. But as the American population grew and the desire for land intensified – particularly after the discovery of gold on Cherokee land in Georgia – the pressure became unbearable. Each subsequent treaty map shows smaller and smaller Indigenous territories, a shrinking island in a rising tide of settler expansion.

Experiencing the Legacy: New Echota and the Cherokee Nation

To begin our immersive journey, consider a visit to New Echota Historic Site in Calhoun, Georgia. This was the capital of the Cherokee Nation from 1825 until their forced removal. Here, you can walk among reconstructed buildings – the Supreme Court, the Council House, the printing office where the Cherokee Phoenix newspaper was published in both English and Cherokee. Looking at a map of New Echota in its prime, then comparing it to a cession map from the 1830s, the contrast is stark. This vibrant, self-governing capital, a testament to Indigenous modernity, was swallowed by the surrounding demand for land. It was here that the Treaty of New Echota, signed by a small, unauthorized faction of the Cherokee Nation, sealed the fate of thousands, despite the vast majority of the nation rejecting its legitimacy.

The Trail of Tears: A Map of Forced Migration

The ultimate expression of land appropriation was the Indian Removal Act of 1830, which paved the way for the forced relocation of these nations to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma). The maps of the Trail of Tears are perhaps the most harrowing. They don’t depict land ownership, but rather routes of suffering – the forced march of thousands of men, women, and children, often in winter, across hundreds of miles.

Where to Trace the Path:

- Trail of Tears National Historic Trail: This isn’t a single path but a network of land and water routes. Visiting segments of the trail – for example, in Red Clay State Historic Park, Tennessee, which served as the last seat of the Cherokee National Council before removal, or along sections of the Tennessee River where boats carried people west – offers a visceral connection. Imagine the maps the U.S. Army used to plan these routes, coldly marking out stages of a death march.

- Museums and Interpretive Centers: The Cherokee Heritage Center in Tahlequah, Oklahoma, or the Choctaw Nation Museum in Tuskahoma, Oklahoma, provide invaluable context, oral histories, and often display reproductions of these cession maps, placing them within the narrative of the people who endured them. These institutions actively counter the colonial narrative often embedded in the maps themselves.

Beyond Cession: The Appropriations of Allotment

Even after the forced removals, the story of land appropriation didn’t end. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the U.S. government enacted the Dawes Act (General Allotment Act of 1887) and subsequent legislation. This policy aimed to break up communally held tribal lands into individual allotments, often 160 acres per family, with the "surplus" land then deemed available for sale to non-Native settlers. The stated goal was to "civilize" Native Americans by forcing them into a Euro-American model of private property and farming. The real outcome was the further diminishment of Indigenous land bases.

Maps from the allotment era show tribal reservations, once established by treaty (even if on vastly reduced lands), being carved up like a pie. The "unallotted" sections are then shown as open to non-Native homesteaders. This was another form of cartographic violence, systematically dissolving tribal land holdings and disrupting traditional ways of life. The impact of allotment is still felt keenly in places like Oklahoma, where much of the land within the historical boundaries of the "Five Civilized Tribes" is now privately owned by non-Natives, creating a checkerboard pattern of jurisdiction and land use.

Counter-Mapping: Reclaiming the Narrative

While these historical maps often represent colonial power and Indigenous loss, Native American communities and scholars are increasingly engaged in "counter-mapping" – creating their own maps that reflect Indigenous perspectives, traditional ecological knowledge, and assertions of sovereignty. These maps might highlight sacred sites, traditional hunting and gathering routes, place names in Indigenous languages, or areas of cultural significance that were ignored or erased by colonial cartography.

Where to See Counter-Mapping in Action:

- National Museum of the American Indian (Washington D.C. & New York City): While not exclusively focused on maps, this museum consistently presents Indigenous perspectives on land, history, and sovereignty. Their exhibits often incorporate historical and contemporary maps to illustrate the ongoing connection to land.

- Tribal Cultural Centers and Archives: Many contemporary Indigenous nations maintain their own archives and cultural centers that present their history and connection to land through their own lens. These are invaluable places to learn directly from the source.

- University Collections and Digital Humanities Projects: Many universities are partnering with Indigenous communities to digitize historical maps and create interactive platforms that allow for the overlay of historical and contemporary Indigenous place names and narratives. Searching for "Indigenous GIS" or "Native American cartography projects" will reveal many such initiatives.

The Enduring Legacy: Resilience and Sovereignty

The review of these maps is not merely an academic exercise; it’s an essential part of understanding the present-day landscape of North America. The lines drawn on those old cession maps continue to shape political boundaries, economic disparities, and cultural identities. They are a constant reminder of broken promises, but also of incredible resilience.

Today, over 574 federally recognized Native American tribes exist in the United States, alongside numerous state-recognized and unrecognized nations. They are sovereign entities, governing their own lands, economies, and cultures. Visiting their reservations and communities, supporting their businesses, and engaging with their cultural institutions is the most meaningful way to connect with this living history.

Your Travel Imperative:

When you travel, don’t just see the land; understand its history. Seek out the museums, the historic sites, and most importantly, the contemporary Indigenous communities that are the living embodiment of this complex cartography. Look at the maps in a new light – not just as static lines, but as dynamic records of human struggle, endurance, and the enduring connection between people and place.

This is a journey that transcends typical tourism. It’s an invitation to engage with a deeper, more challenging, but ultimately more rewarding understanding of the land beneath your feet. It’s a journey into the heart of America’s true cartography, a map of power, loss, and the unbroken spirit of its first peoples. Forget the glossy maps; the real story is etched in the land itself, waiting to be understood.