The Hudson Valley, a tapestry of rolling hills, dramatic cliffs, and the majestic river itself, is often celebrated for its colonial estates, artistic movements, and revolutionary war history. Yet, beneath these familiar layers lies an older, profound narrative, one etched not in stone or parchment, but in the very landscape—the maps of its original inhabitants, the Indigenous peoples whose understanding of this land predates recorded history. For the discerning traveler, to truly experience the Hudson Valley is to learn to read these ancient maps, to see the world through the eyes of the Lenape (Munsee-speaking bands) and Mohican (Mahican) nations who called this valley home for millennia.

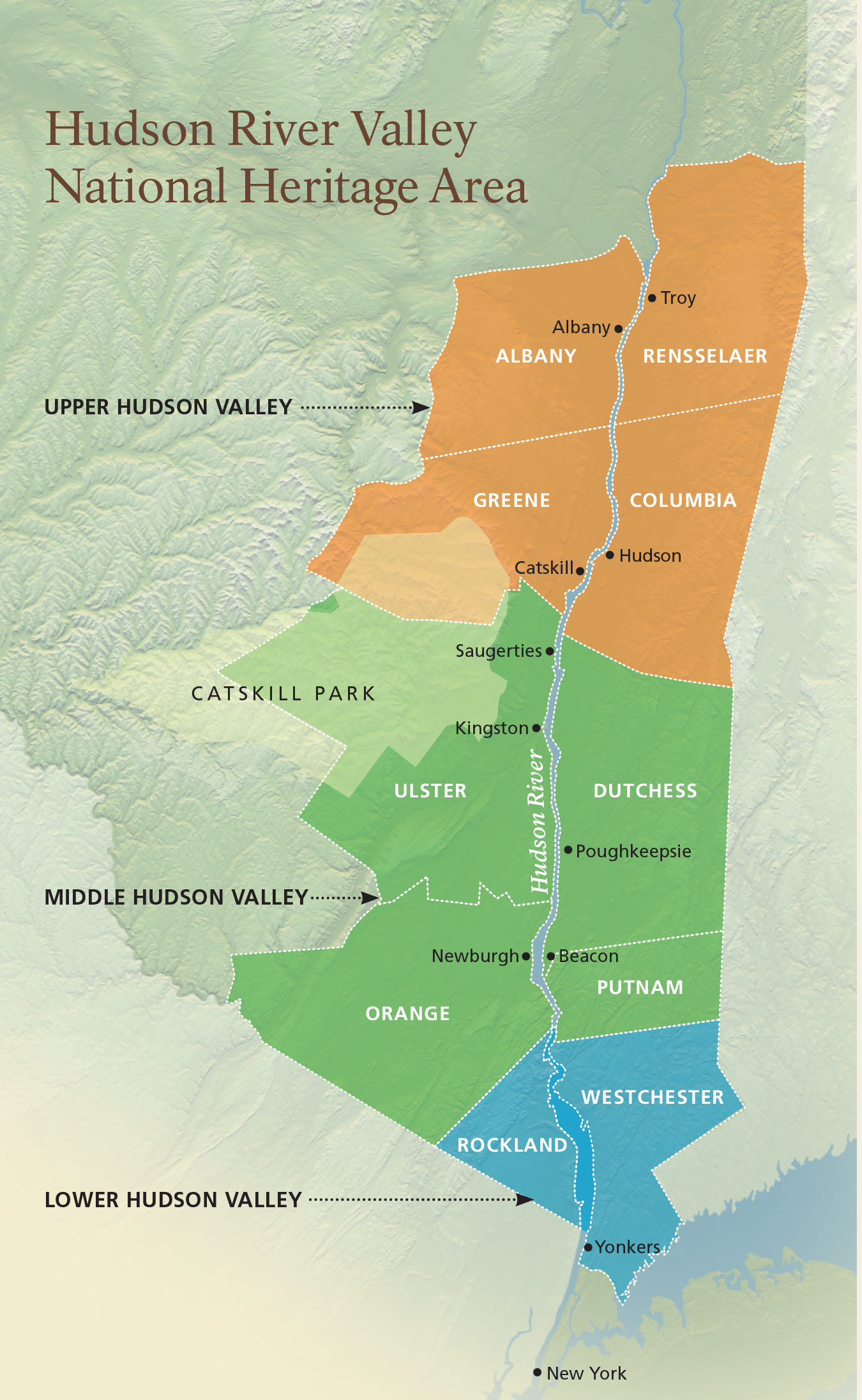

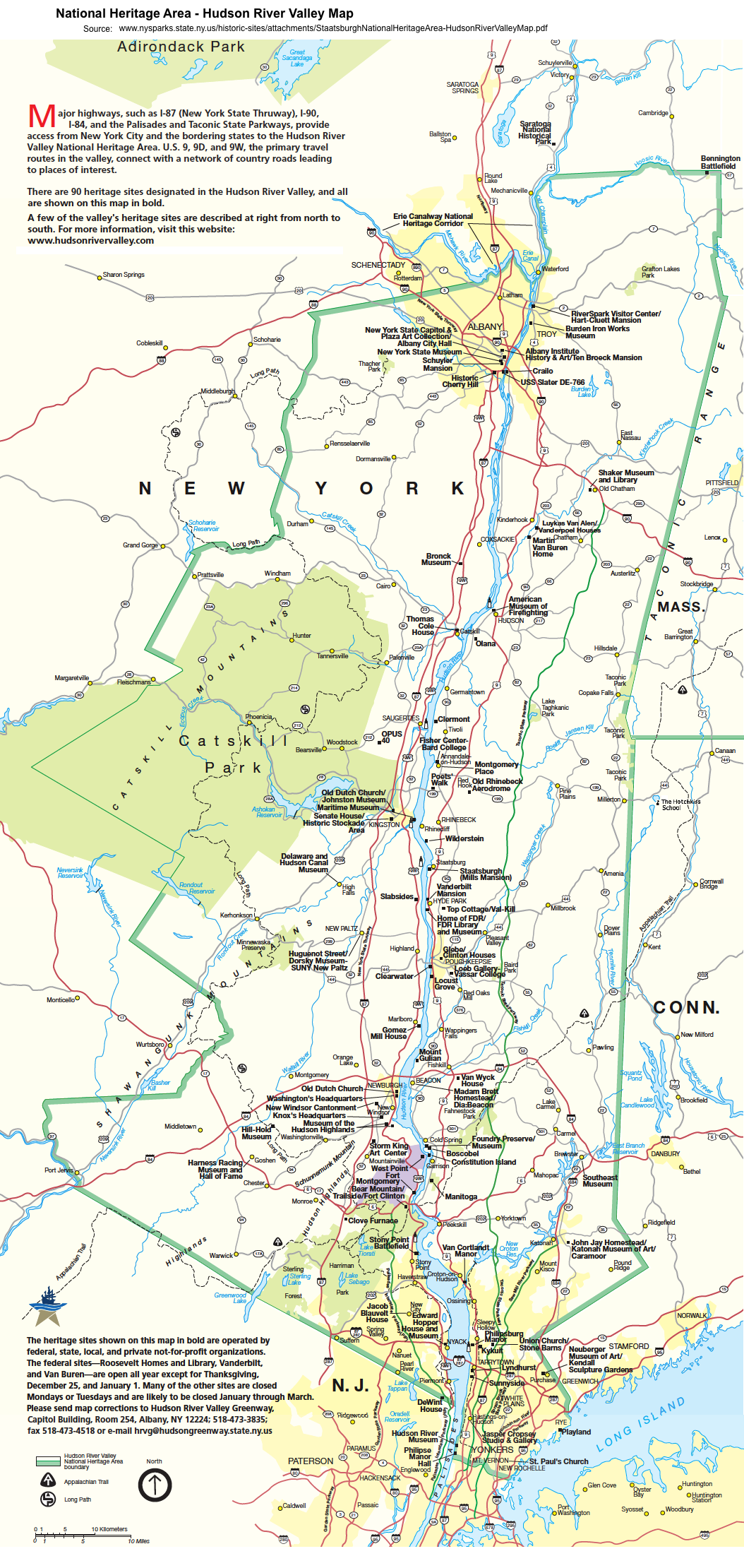

Forget the conventional paper maps; Indigenous cartography of the Hudson Valley was a living, breathing knowledge system, passed down through generations. These "maps" were embedded in oral traditions, mnemonic devices, songs, and ceremonies, guiding people not just across physical space but through cultural and spiritual landscapes. They detailed hunting grounds, fishing spots, sacred sites, seasonal gathering areas, portage routes, and trade pathways. The Hudson River, known to the Mohicans as Mahicannituck—"the river that flows both ways" due to its tidal nature—was not merely a geographic feature but the central artery of their world, a highway connecting communities from its headwaters in the Adirondacks to the Atlantic.

To begin unraveling these ancient maps, one must first appreciate the river itself. Imagine standing atop Storm King Mountain, its rugged profile commanding one of the most iconic views of the Hudson Highlands. From this dizzying height, the river snakes through the landscape, a ribbon of silver and blue. This vantage point, offering sweeping panoramas of both sides of the river and its intricate network of coves and tributaries, would have been invaluable. It was a strategic lookout, a place to observe the movement of game, the approach of visitors, or the changing seasons. The winding trails that ascend Storm King today likely follow ancient footpaths, meticulously maintained over centuries, connecting upland hunting camps to riverine settlements. A hike here is more than just exercise; it’s an opportunity to physically trace steps taken by countless generations, to feel the same wind, and gaze upon the same, largely unchanged, vistas.

The river’s tributaries were equally critical arteries. Consider the Esopus Creek, which empties into the Hudson near Kingston. This creek, and the surrounding fertile lands, were central to the Lenape peoples, particularly the Esopus band. Following its course, whether by foot along modern trails or by kayak through its calmer sections, reveals a different kind of map. Here, the focus shifts from grand vistas to intimate details: the bends in the river that might hide a prime fishing spot, the sheltered banks ideal for temporary encampments, the confluence points where different paths converged. These were the highways of smaller canoes, the access points to deeper forests and fertile floodplains. To paddle the Esopus is to understand the rhythm of a smaller waterway, its subtle currents and hidden corners, just as Indigenous navigators would have.

.png)

Further north, the Catskill Creek offers similar insights into Mohican territories. Flowing down from the Catskill Mountains, this creek was a vital conduit for resources and travel. The area around its mouth, near the modern-day town of Catskill, was a significant trading hub. When one explores places like the Cohotate Preserve along the Catskill Creek, the natural features—the bluffs, the marshlands, the access to the Hudson—become legible as markers on an ancient map. These were not arbitrary locations but places chosen for their strategic advantage, their abundance of resources, or their spiritual significance. Visiting these less-trafficked natural preserves allows for a deeper immersion, a chance to quiet the modern mind and listen for the echoes of ancient footsteps and paddles.

The mountains themselves formed another layer of this Indigenous cartography. The Catskills to the west and the Taconic Range to the east were more than just scenic backdrops; they were navigational landmarks, sources of medicinal plants, and spiritual refuges. The Kaaterskill Clove in the Catskills, with its dramatic waterfalls and steep ravines, was not just a beautiful place but a powerful, sacred site, its features likely incorporated into origin stories and ceremonial practices. Exploring a trail like the one to Kaaterskill Falls allows a traveler to connect with this raw, untamed power of the land, to feel the immensity that would have inspired awe and reverence. These high places offered not just physical orientation but spiritual grounding.

To truly understand these maps, a traveler must also consider the subtle shifts in topography that marked different resource zones. The fertile floodplains along the river were prime agricultural lands for corn, beans, and squash. The upland forests provided deer, bear, and various small game, as well as nuts and berries. Wetlands were sources of reeds for baskets and mats, and waterfowl. Each feature, whether a prominent mountain peak or a humble berry patch, held a specific place on the mental map of its people.

One contemporary site that offers a unique perspective on this ancient landscape is Olana State Historic Site, the former home of Hudson River School painter Frederic Church. While Church’s vision was distinctly European-Romantic, his chosen vantage point atop a hill overlooking the Hudson, with the Catskills in the distance, captures the very essence of the Indigenous "map." From Olana’s sweeping vistas, one can trace the river’s path, identify distant peaks, and imagine the interconnectedness of the entire valley. It’s a place to contemplate how a landscape, viewed from a specific point, reveals its underlying structure, a structure that was fundamentally understood and utilized by Indigenous communities long before Church ever set up his easel. It’s a testament to the enduring power of the land itself as a source of knowledge.

Another compelling experience is crossing the Walkway Over the Hudson in Poughkeepsie. This repurposed railway bridge offers an unparalleled linear perspective of the river. Suspended high above the water, you get a bird’s-eye view of the river’s width, its currents, and the surrounding banks. It’s an ideal spot to visualize the river as a busy thoroughfare, teeming with canoes, bustling with trade, and serving as a boundary and a connector between different communities. Imagine the communication across the river, the signaling, the crossing points that would have been well-known and utilized. This modern marvel ironically provides a window into ancient movements.

The Indigenous maps also included intangible elements: sacred sites, burial grounds, and places of spiritual power. While many of these are no longer overtly marked or accessible, their presence is subtly felt in the enduring place names that pepper the valley: Wappinger, Esopus, Katonah, Mohonk. These names, often corrupted from their original Indigenous forms, are linguistic echoes of a vibrant past, signposts on an invisible map. To encounter these names is to be reminded of the people who first named these places, imbuing them with meaning long before European settlement.

For the conscientious traveler, truly engaging with the Native American maps of the Hudson Valley requires more than just visiting scenic spots. It demands a shift in perspective, an active imagination, and a commitment to learning. It means:

- Hiking with intention: Not just seeing the view, but understanding its significance.

- Paddling with awareness: Feeling the flow of the water, imagining the journey.

- Visiting local historical societies and museums: Seeking out exhibits or resources that specifically address Indigenous history, often working in conjunction with local Native American communities.

- Reading Indigenous perspectives: Engaging with books, articles, and oral histories from the Lenape and Mohican peoples themselves.

- Acknowledging the land: Understanding that every step taken in the Hudson Valley is on ancestral lands, and showing respect for that heritage.

The Hudson Valley is a land of profound beauty and layered history. By learning to read its ancient maps, by understanding the landscape through the eyes of its first inhabitants, travelers can unlock a deeper, richer experience. It’s an invitation to look beyond the picturesque surface and connect with the enduring spirit of a land that has been mapped, loved, and lived upon for thousands of years, a journey that transforms a simple scenic drive into a pilgrimage through time.