Walking the Ancient Arteries: Tracing the Haudenosaunee War Paths Through the Lake George-Lake Champlain Corridor

Forget dusty archives and static maps for a moment. To truly grasp the strategic genius and indomitable spirit of the Iroquois Confederacy – the Haudenosaunee – you must walk their ground. Not just any ground, but the very arteries of conflict and diplomacy that defined their world for centuries. My recent journey into the Lake George-Lake Champlain corridor wasn’t just a scenic drive; it was a profound immersion into one of North America’s most pivotal historical war paths, a living map etched into the landscape itself.

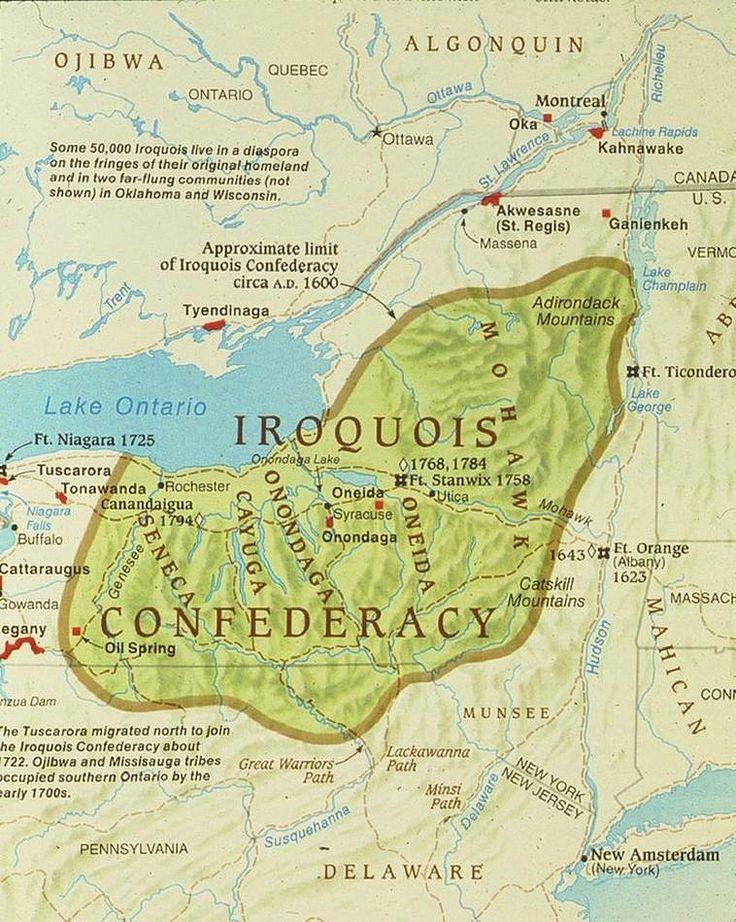

This narrow, watery corridor, stretching from the headwaters of Lake George north to the Richelieu River, was not merely a trade route or a hunting ground. It was the Great War Path, a superhighway of movement for the Haudenosaunee, their allies, and their adversaries. For the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, and Seneca – the Five (later Six) Nations – control and mastery of this path were paramount. Their historical war paths maps, though not always drawn on parchment, were deeply ingrained in their knowledge of the land: the portages, the hidden bays, the strategic heights, the best places to make camp or lay an ambush. My goal was to experience this landscape through their historical lens, to feel the weight of countless journeys, raids, and diplomatic missions that unfolded here.

The journey begins, perhaps appropriately, at the southern tip of Lake George. Today, it’s a bustling tourist town, but peel back the layers of modern amusement and you stand on ground soaked in history. The Lake George Battlefield Park offers the first tangible connection. As I walked through the serene grounds, past monuments to colonial-era battles, it was crucial to remember that these conflicts were often fought on or for control of these ancient Indigenous pathways. The Haudenosaunee understood the geography here intimately. They knew the flow of the water, the density of the forests, the best vantage points. For them, this wasn’t just a battlefield; it was a carefully chosen segment of their strategic network, a vital link in their geopolitical strategy that stretched from the Atlantic to the Mississippi.

Moving north, the lake narrows, and the strategic importance of the corridor becomes strikingly clear. The steep, forested hills that hem in Lake George and, further on, Lake Champlain, create a natural funnel. There are few alternative routes, making this corridor an unavoidable choke point. It’s easy to imagine fleets of bark canoes, silent and swift, navigating these waters, carrying warriors, diplomats, and trade goods. These were the "roads" of the Haudenosaunee – not paved, but known with a precision that modern GPS often lacks, passed down through generations.

The true heart of this historical war path experience lies at Fort Ticonderoga. Perched majestically on a promontory overlooking the confluence of Lake George and Lake Champlain, Ticonderoga (or Carillon to the French) was the ultimate strategic prize. Walking the grounds of this meticulously restored fort, one is immediately struck by its commanding views. From its ramparts, you can survey miles of the lake in both directions, understanding why the Haudenosaunee would have valued – and fiercely contested – this very spot long before European fortifications rose.

The fort’s interpretive displays and living history demonstrations are excellent, but to truly connect with the Iroquois Confederacy’s presence, one must look beyond the European narratives. The Haudenosaunee were not merely bystanders or auxiliaries in the French and Indian War or the American Revolution; they were central actors whose alliances, neutrality, or opposition profoundly shaped outcomes. Their war paths, meticulously mapped in their collective memory, guided their movements in crucial campaigns, allowing them to appear, seemingly from nowhere, to strike or to parley. The paths they used to approach Ticonderoga, whether by water or through the dense surrounding forests, were part of a sophisticated military doctrine. They knew the land, its hiding places, its resources, in a way no European army ever could.

Standing on the bluffs at Ticonderoga, looking north towards the broad expanse of Lake Champlain, the sheer scale of the corridor unfolds. This lake, often called the "Sixth Great Lake," was another vital artery. Its length and depth allowed for rapid movement, making it ideal for large-scale expeditions. The Haudenosaunee utilized its shores and islands for temporary encampments, supply caches, and ambush points. Their historical war paths maps weren’t just about the routes themselves, but also about the critical infrastructure – the places to rest, hunt, and strategize along the way.

Further north along Lake Champlain, Crown Point State Historic Site offers another powerful vantage point. While less dramatic than Ticonderoga, the ruins of the British and French forts here speak volumes about the persistent struggle for control over this critical corridor. For the Haudenosaunee, these forts represented a constant encroachment, a challenge to their sovereignty and their traditional use of these vital paths. Their response was often swift and strategic, leveraging their intimate knowledge of the surrounding wilderness – the true "map" – to outmaneuver or outlast their European rivals.

To truly immerse oneself in the spirit of these war paths, however, one must leave the forts behind and embrace the natural landscape. Hiking the numerous trails that snake through the Adirondack foothills around Lake George and Lake Champlain offers a tangible connection. Imagine stepping through forests that have witnessed centuries of passage. The rustle of leaves, the call of a distant bird – these are the sounds that accompanied Haudenosaunee warriors and diplomats on their journeys. Paddling a kayak or canoe on the lakes themselves is perhaps the most profound experience. Gliding across the water, feeling the current, seeing the shoreline as it would have appeared to those ancient travelers, allows for a visceral understanding of how these waterways functioned as the very essence of their mobility. You become a part of the historical war paths maps, tracing lines of movement across the water.

This journey is not just about appreciating the past; it’s about understanding the present. The enduring legacy of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy is not confined to history books. Their strategic thinking, their deep connection to the land, and their resilience continue to resonate. Visiting these sites, one gains a profound respect for their sophisticated military and diplomatic strategies, which were inextricably linked to their mastery of the land and its pathways. Their "maps" were not abstract drawings, but an intimate, experiential knowledge of every rise, fall, river, and portage.

For the modern traveler, this experience requires a shift in perspective. Instead of merely viewing these as scenic attractions or sites of colonial battles, consider them as segments of a vast, ancient network. Look beyond the visible fortifications to the invisible paths that crisscrossed the land and water, pathways that enabled the Haudenosaunee to maintain their power and influence for centuries.

Practicalities for the Journey:

- Best Time to Visit: Late spring (May-June) or early autumn (September-October) offers pleasant weather, fewer crowds, and stunning foliage. Summer is popular but can be very busy.

- Getting There: A car is essential to navigate between sites. The corridor is easily accessible from major highways in New York.

- Key Locations: Don’t miss Lake George Battlefield Park, Fort Ticonderoga, and Crown Point State Historic Site.

- Immersive Activities: Prioritize hiking trails that offer panoramic views or follow historical routes, and definitely consider renting a kayak or canoe to experience the waterways. Many local outfitters offer rentals.

- Accommodation: Options range from rustic camping in the Adirondacks to charming B&Bs and hotels in Lake George, Ticonderoga, and Plattsburgh.

- Respectful Engagement: Remember that these are not just historical sites but places of deep cultural significance for the Haudenosaunee people. Seek out and support Indigenous-led initiatives or cultural centers if available to gain further perspective. Look for interpretive signs that tell the story from an Indigenous viewpoint.

My journey through the Lake George-Lake Champlain corridor was more than just a trip; it was a revelation. It transformed my understanding of the Iroquois Confederacy, showing me that their power wasn’t just in their warriors or their diplomacy, but in their profound, strategic relationship with the land itself. Their historical war paths maps weren’t just lines on a page; they were the very veins and arteries of their existence, still palpable for those willing to walk them with an open mind and a discerning eye. To stand on these ancient paths is to connect with a powerful, enduring legacy that shaped a continent. It’s a journey I urge every intrepid traveler to undertake.