Tracing the Echoes: A Traveler’s Guide to Tsimshian Historical Potlatch Sites and Their Unwritten Maps

The Pacific Northwest Coast of British Columbia, a region of breathtaking fjords, ancient rainforests, and islands shrouded in mist, is more than just a landscape of unparalleled natural beauty. It is a living, breathing testament to millennia of Indigenous culture, particularly that of the Tsimshian Nation. For the discerning traveler seeking a journey beyond the picturesque, an exploration of Tsimshian historical potlatch sites offers an immersive dive into one of the world’s most sophisticated and enduring cultures. This isn’t a trip where you simply follow a marked trail on a conventional map; it’s an invitation to understand a deeper cartography, one woven from oral tradition, ecological knowledge, and the profound respect for place.

The Potlatch: A Cultural Cornerstone and Its Enduring Legacy

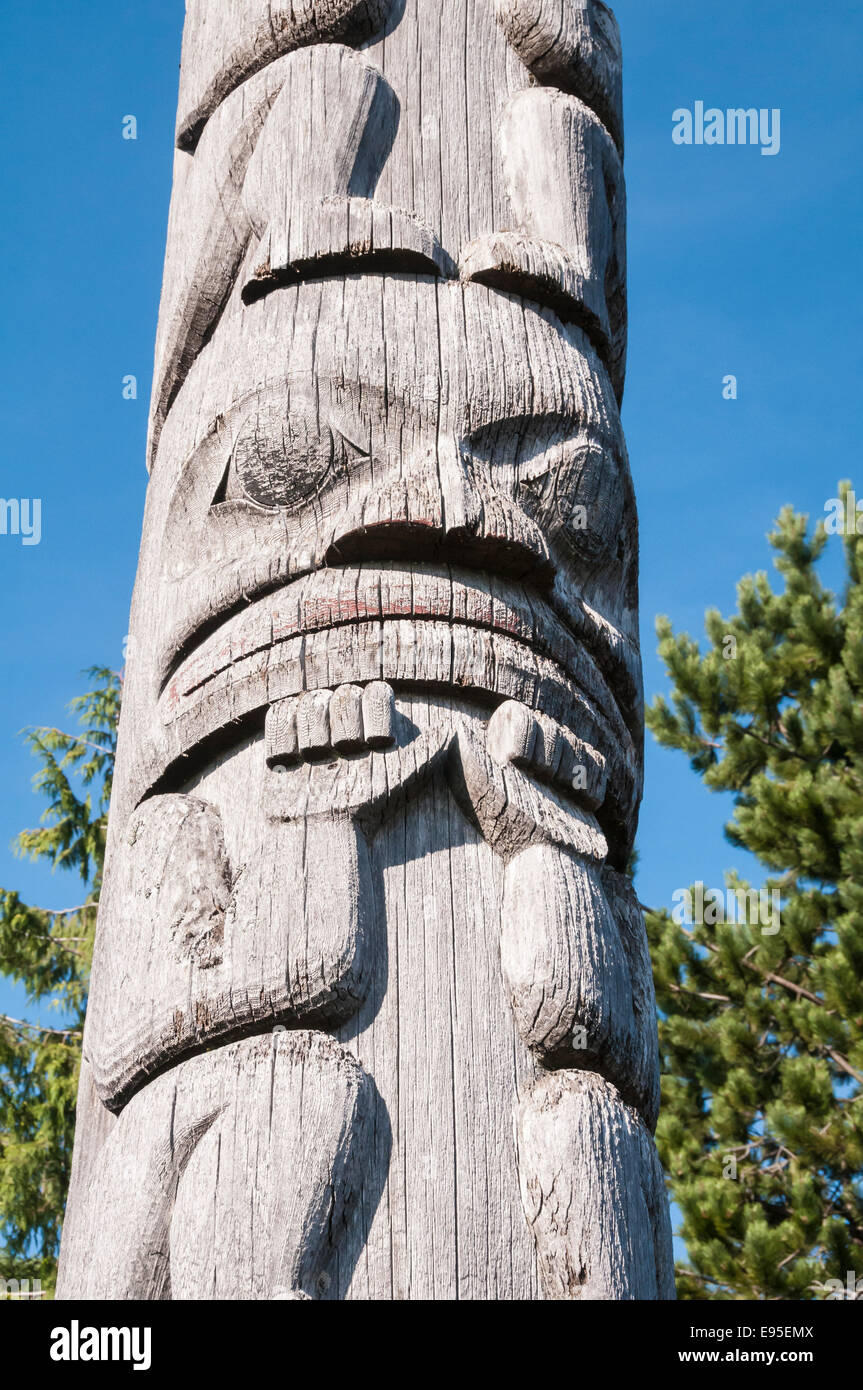

To understand Tsimshian historical sites, one must first grasp the significance of the potlatch. Far from being a mere feast or celebration, the potlatch was, and remains, the bedrock of Tsimshian society. It was a complex system of governance, economic redistribution, spiritual practice, and social validation. During a potlatch, hosts would display their wealth, validate claims to names, territories, and privileges, mourn the deceased, celebrate marriages, and raise totem poles, all through elaborate ceremonies, dances, songs, and the lavish distribution of gifts. This was where history was recounted, laws were upheld, and the social fabric was strengthened.

Colonial powers, viewing the potlatch as an impediment to assimilation and an economically "wasteful" practice, banned it in Canada for over 60 years (1884-1951). Despite this oppressive period, Tsimshian people continued to practice potlatches in secret, ensuring the survival of their traditions. Today, the potlatch has undergone a powerful revival, a vibrant testament to Tsimshian resilience and cultural strength.

The Challenge of Mapping the Intangible

For the traveler eager to connect with these historical sites, the concept of "maps" takes on a unique dimension. Unlike European historical sites marked by crumbling castles or clearly defined ruins, Tsimshian potlatch sites, often dating back hundreds or even thousands of years, manifest differently in the landscape. Traditional longhouses, built from cedar, eventually returned to the earth, leaving subtle depressions or raised platforms. Totem poles eventually decayed, their stories absorbed by the forest.

Therefore, the "maps" to these places are not solely paper charts with X’s marking archaeological digs. They are multi-layered:

- Oral Histories and Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK): The most vital "map" is held within the memory and knowledge of Tsimshian elders and community members. These oral traditions describe specific locations, the events that transpired there, the resources gathered, and the spiritual significance of the land. This is an ongoing, living map.

- Archaeological Surveys: Professional archaeologists, often working in collaboration with Tsimshian communities, use modern techniques to identify village sites, midden heaps (accumulations of shells and other domestic waste), house platforms, and other indicators of past human activity. These surveys often confirm and complement oral histories.

- Modern Community-Led Mapping Projects: Many Tsimshian communities are actively engaged in mapping their traditional territories, documenting historical sites, place names in Sm’algya̱x (the Tsimshian language), and resource-use areas. These projects are crucial for cultural preservation, land claims, and educational purposes.

- The Landscape Itself: For the trained eye, the landscape speaks volumes. A sudden flattening in a slope, a cluster of ancient cedars, or an unusually rich patch of berries can all be subtle indicators of a former village or potlatch site.

Navigating the Tsimshian Homelands: Where to Begin Your Journey

The Tsimshian Nation comprises fourteen distinct First Nations, traditionally divided into three main groups based on their geographic location: the Coast Tsimshian (along the coast and islands), the Southern Tsimshian (on the islands south of Prince Rupert), and the Gitksan and Nisga’a (inland along the Skeena and Nass Rivers, though often considered distinct Nations with related languages). While specific historical potlatch sites are often on unceded ancestral lands, respectful engagement with the communities is paramount.

Your journey would likely focus on the traditional territories around Prince Rupert, the Skeena River estuary, and the surrounding islands. Key Tsimshian communities in this area include:

- Lax Kw’alaams (Port Simpson): Historically a major gathering place and trading hub, and a significant potlatch site. The remnants of ancient village sites and shell middens are found in the surrounding areas.

- Metlakatla: Located on Metlakatla Pass, an area rich in history and traditional resource gathering. It offers insights into early contact and the Tsimshian way of life.

- Gitxaala (Kitkatla): Situated on Dolphin Island, this community holds deep connections to ancestral lands and marine resources, with numerous historical sites in its traditional territory.

- Gitga’at (Hartley Bay): Further south, the Gitga’at territory is pristine wilderness, home to numerous ancient village sites and culturally significant locations accessed primarily by boat.

- Kitsumkalum and Kitselas: Located further up the Skeena River, these communities have historical sites along the riverbanks, including ancient village platforms, petroglyphs, and resource harvesting areas that would have supported potlatch economies.

The Experience of Visiting: More Than Just Sightseeing

Visiting a Tsimshian historical potlatch site is not like visiting a meticulously preserved ruin. It is an experience that demands respect, imagination, and often, the invaluable guidance of a local Tsimshian guide.

- Guided Tours are Essential: This cannot be stressed enough. A local Tsimshian guide provides not just navigation, but the critical cultural context, oral histories, and insights that bring a place to life. They can point out subtle landscape features that denote a former longhouse site, explain the significance of certain plant species, or recount the stories of ancestral chiefs who hosted grand potlatches on that very ground. Without this guidance, you might walk right past millennia of history without realizing it.

- Immerse Yourself in Nature: These sites are often nestled within breathtaking natural environments – ancient forests, pristine coastlines, and powerful rivers. The journey to the site is as much a part of the experience as the destination itself. Observe the salmon runs, the eagles soaring overhead, and the lush temperate rainforest. These natural elements were integral to the potlatch economy and worldview.

- Visualizing the Past: At a historical village site, you might see subtle depressions in the earth, indicating where longhouses once stood, or mounds of shell middens, hinting at centuries of feasts. Imagine the vibrant activity: the smoke rising from longhouse fires, the rhythmic drumming and singing, the elaborate regalia worn by dancers, the murmur of hundreds of people gathered for ceremony.

- Connect with the Present: Your journey should extend beyond historical sites to engage with contemporary Tsimshian culture. Visit local cultural centers, art galleries featuring Tsimshian artists, and if possible, attend public cultural events (always with respect and invitation). This reinforces that Tsimshian culture is vibrant and ongoing, not merely a relic of the past.

- A Sense of Sacredness: Many of these sites hold deep spiritual significance for the Tsimshian people. Approach them with reverence, understanding that you are on ancestral land that continues to be spiritually active.

Practicalities for the Respectful Traveler

- Seek Permission and Guidance: Always engage with the local Tsimshian Nation or designated cultural tourism operators before planning a visit to ancestral lands. Many communities offer guided tours that ensure respectful access and provide invaluable interpretation.

- Support Local Indigenous Tourism: Choose tour operators and businesses owned or operated by Tsimshian people. This directly benefits the communities whose history and culture you are exploring.

- Leave No Trace: Practice strict "leave no trace" principles. Pack out everything you pack in, stay on designated paths (if any), and do not disturb any natural or historical features.

- Be Prepared for Wilderness Travel: Accessing many of these sites involves boat travel, hiking through uneven terrain, and exposure to coastal weather. Dress in layers, bring appropriate gear, and inform others of your travel plans.

- Learn Basic Cultural Etiquette: Familiarize yourself with Tsimshian history, protocols, and respect for elders and traditional knowledge. A genuine interest and open mind are the best tools for respectful engagement.

- Understand the Sensitivity: The history of Indigenous peoples in Canada is marked by colonization, trauma, and resilience. Approach your visit with an understanding of this context, acknowledging the ongoing efforts towards reconciliation and cultural revitalization.

Beyond the Map: A Journey of Understanding

Exploring Tsimshian historical potlatch sites is not a conventional tourist activity; it is a profound journey into the heart of an ancient and enduring culture. It challenges the Western notion of "maps" and invites travelers to listen to the whispers of the past, carried on the wind and through the voices of those who know the land intimately. It’s an opportunity to witness the resilience of a people, to learn about a sophisticated societal structure, and to gain a deeper appreciation for the intricate relationship between people, place, and tradition.

By choosing to engage respectfully, support Indigenous-led initiatives, and approach these sacred spaces with an open heart, travelers can forge a connection not just with history, but with the living spirit of the Tsimshian Nation, a journey that promises to be as transformative as the landscape itself. It’s an adventure that leaves an indelible mark, enriching your understanding of the world and the enduring power of culture.