Forget everything you think you know about maps. For centuries, Western cartography has trained us to see the world as a grid of lines, political borders, and geographical features labeled with Latin script. But what if the land itself was a living document? What if maps weren’t static paper but dynamic narratives woven into the very fabric of existence?

This isn’t just a philosophical musing; it’s the profound reality of Native American mapping traditions. For travelers and researchers alike, unlocking these indigenous cartographies offers a revolutionary way to understand the places we visit, transcending mere sightseeing to a deep, respectful engagement with history, culture, and ecology. This article isn’t a review of a physical place, but rather a "review" of a transformative approach to understanding any location – a method that turns the entire North American continent, and indeed the world, into an "Unseen Atlas" waiting to be explored through indigenous eyes.

The Unseen Atlas: A Review of the Native American Cartographic Experience

The "Location": The Land Itself, Viewed Through Indigenous Lenses

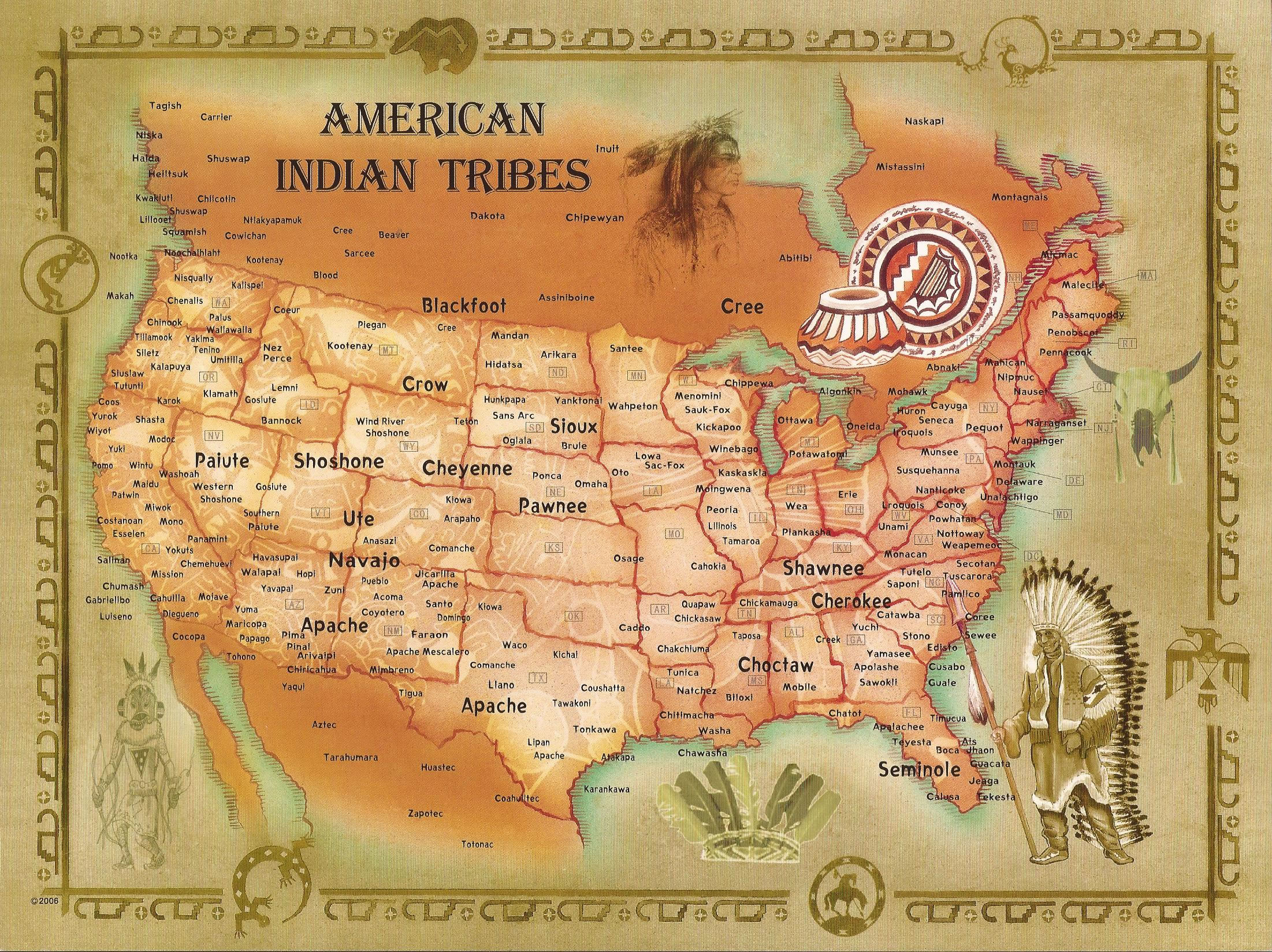

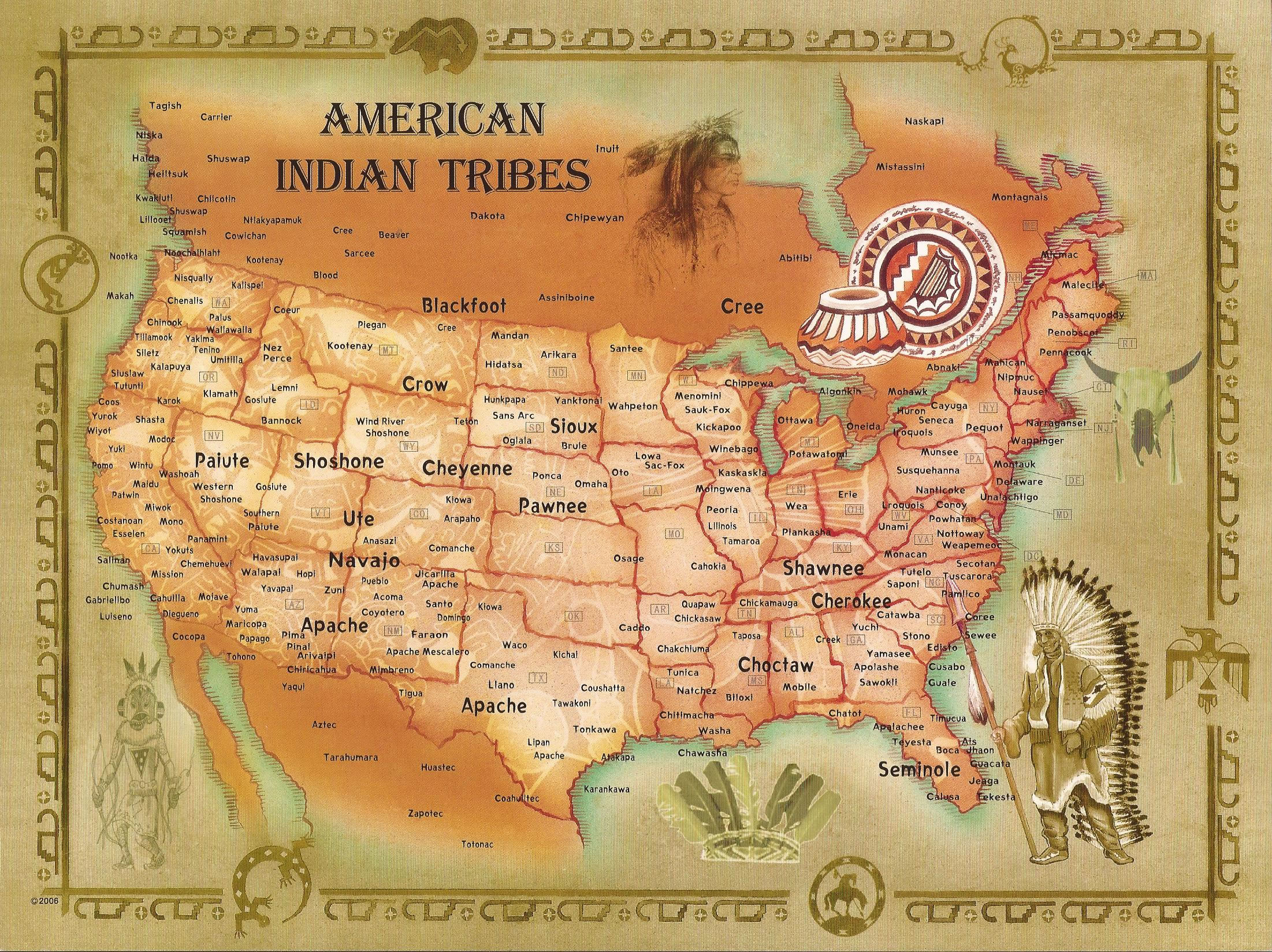

Instead of a specific museum or archive, our "location" for this review is the concept of the land as a primary indigenous map. Imagine walking through a national park, a vast desert, or along a winding river. Western maps show you trails, elevation, and perhaps geological features. Native American maps, however, reveal layers of meaning: ancestral migration routes, sacred sites, resource locations, historical events, spiritual narratives, and ecological wisdom. The land is not just on the map; it is the map.

What’s Being "Reviewed": The Methodology and Its Revelations

This "review" focuses on the process of engaging with Native American maps for research and travel, highlighting its immense value and the profound shifts in perspective it demands. It’s an invitation to step beyond the familiar and embrace a cartographic tradition rooted in relationship, memory, and spiritual connection.

Features of the Unseen Atlas:

- Dynamic and Multi-Dimensional: Unlike static paper maps, indigenous maps are often fluid. They can be embodied in oral histories, sung in ceremonies, painted on hide, etched into rock, woven into textiles, or even manifested in landscape modifications. They are less about precise coordinates and more about relationships, journeys, and the flow of life.

- Culturally Rich Narratives: Every feature on an indigenous map tells a story. A mountain isn’t just a peak; it might be a deity, a site of creation, or the place of a pivotal battle. A river isn’t just a waterway; it’s a lifeline, a boundary, a spiritual pathway, or the scene of ancestral crossings. These maps are repositories of cultural memory and identity.

- Ecological Wisdom: Native American maps are often deeply intertwined with environmental knowledge. They pinpoint seasonal resources, migration patterns of animals, sustainable harvesting areas, and safe passages through challenging terrain. This knowledge, honed over millennia, is invaluable for understanding past and present ecological systems.

- Sacred Geographies: Many indigenous maps delineate sacred spaces, ceremonial routes, and spiritual connections to the land. Understanding these geographies fosters a deeper appreciation for the spiritual significance of places and promotes respectful interaction.

How to Navigate the Unseen Atlas: A Practical Guide for Researchers and Travelers

Engaging with Native American maps requires a fundamental shift in perspective and a commitment to respectful, ethical research. Here’s how to begin your journey:

Step 1: Shift Your Cartographic Paradigm

Before you even look for a map, understand that Native American cartography is rarely about fixed points and objective measurements. It’s subjective, relational, and deeply personal to the people who created it. It prioritizes memory, narrative, and ecological awareness over Euclidean geometry. Embrace this difference; it’s where the richness lies.

Step 2: Start with the Landscape Itself (Direct Observation and Indigenous Place Names)

Your journey begins on the ground. Pay attention to the natural world around you. What are the prominent features? How do they connect?

- Indigenous Place Names: Researching indigenous place names for an area is one of the most direct ways to access Native American cartography. Names like "Chattahoochee" (meaning "painted rocks" or "flowering rocks" in Creek) or "Mississippi" ("great river" in Ojibwe) are not just labels; they are concise descriptions, historical markers, or spiritual references that reveal how indigenous people understood and interacted with their environment. These names often describe the land’s use, its resources, or its mythological significance.

- Oral Histories: Seek out published oral histories or, even better, engage with tribal elders (with appropriate protocols and permissions). Many "maps" exist purely in spoken tradition, describing journeys, resource locations, and significant events tied to specific geographical features.

Step 3: Consult Indigenous Knowledge Keepers and Tribal Archives

This is paramount. The most authentic and respectful way to understand Native American maps is directly from the source.

- Tribal Cultural Centers and Archives: Many Native American nations have established their own cultural centers, museums, and archives. These institutions are invaluable repositories of indigenous knowledge, often holding maps, oral histories, and cultural artifacts that are not found elsewhere. They are also vital for understanding the context and meaning of these materials from an indigenous perspective. Always contact them first, explain your research, and respect their protocols.

- Elders and Community Members: If possible and appropriate, seeking guidance from tribal elders or community knowledge keepers can provide unparalleled insights. This requires immense respect, patience, and a willingness to listen. Be prepared to offer compensation for their time and knowledge, and always adhere to their guidance regarding what information can be shared and how it can be used.

Step 4: Explore Public Institutions with Caution and Criticality

Many public institutions house Native American cartographic materials, often collected during periods of colonization. While these can be valuable, it’s crucial to approach them critically, understanding the context of their collection.

- Library of Congress, National Archives, Smithsonian Institution: These major institutions hold vast collections, including early European maps that incorporate indigenous knowledge, "copy maps" made by non-Natives based on indigenous accounts, and a growing collection of indigenous-created materials. Search their digital archives and reach out to their specialized departments.

- University Libraries and Special Collections: Many universities, particularly those with strong Native American Studies programs, have significant collections of maps, ethnographic notes, and related documents.

- Museums: Anthropological and historical museums often display or house indigenous maps (e.g., hide paintings, birchbark scrolls, wampum belts). Pay attention to the provenance and interpretation provided.

Step 5: Decipher Diverse Cartographic Formats

Native American maps come in a breathtaking array of forms:

- Oral Maps: The most prevalent form. These are stories, songs, and mnemonic devices that encode geographical information. Look for patterns, repeated place names, and directional cues within narratives.

- Petroglyphs and Pictographs: Rock art often depicts journeys, resource locations, astronomical observations, and spiritual geographies. Understanding the cultural context is key to interpretation.

- Hide Paintings and Birchbark Scrolls: Used by Plains nations and Northeastern Woodlands peoples, respectively, these were often travel maps, historical records, or ceremonial diagrams. Look for recurring symbols, pathways, and depictions of significant landmarks or events.

- Wampum Belts: While primarily diplomatic records, some wampum belts also conveyed geographical information, particularly in depicting alliances or territorial agreements.

- "Stick Maps" (e.g., Inuit Anirnisiit): Carved wooden objects used by Inuit navigators to map coastlines and sea currents, allowing them to "feel" the route in the dark or fog.

- Sand Paintings: Ceremonial maps created for healing or spiritual purposes, often depicting sacred landscapes and cosmic journeys. These are temporary and deeply sacred.

When encountering these forms, remember that they are not literal representations in the Western sense. They are often symbolic, metaphorical, and highly condensed.

Step 6: Cross-Reference and Interpret (with Humility)

- Compare with Western Maps: Use modern topographical maps and satellite imagery to identify geographical features mentioned in indigenous accounts. This can help you ground abstract narratives in the physical world.

- Archaeological and Ecological Data: Correlate indigenous maps with archaeological findings, environmental studies, and historical records. This interdisciplinary approach can reveal layers of human-environment interaction.

- Contextualize: Always strive to understand the cultural, historical, and spiritual context in which a map was created. Who made it? For what purpose? Who was the intended audience?

Step 7: Acknowledge, Attribute, and Respect

The ethical dimensions of using Native American maps cannot be overstated.

- Attribution: Always credit the source, whether it’s a specific tribe, an elder, or an archive.

- Permission: For contemporary research or public sharing, seek explicit permission from tribal authorities, especially for sensitive or sacred information.

- Avoid Misappropriation: Do not claim indigenous knowledge as your own. Understand that some information is sacred and not intended for public dissemination.

- Reciprocity: Consider how your research can benefit the indigenous communities whose knowledge you are using. This could be through sharing findings, supporting tribal initiatives, or advocating for indigenous rights.

The Journey’s Reward: A Transformed Perspective

Engaging with Native American maps is not merely an academic exercise; it’s a profound journey of discovery that enriches both the researcher and the traveler.

For the Traveler: Your perception of a landscape will be irrevocably altered. A simple hiking trail becomes an ancient trade route. A seemingly unremarkable hill becomes a place of spiritual significance. You move from being a passive observer to an informed participant in a living history. It fosters a deeper sense of connection, respect, and stewardship for the places you visit.

For the Researcher: This methodology offers unparalleled insights into indigenous land tenure, environmental management, historical movements, and cultural resilience. It challenges colonial narratives, amplifies indigenous voices, and contributes to a more holistic and accurate understanding of North American history. It pushes the boundaries of what cartography can be, moving beyond mere spatial representation to embody worldview, memory, and identity.

Conclusion: Reviewing the Path Forward

The "Unseen Atlas" of Native American cartography is not an easy read. It demands patience, humility, and a willingness to decolonize your own understanding of space and knowledge. But for those who embark on this journey, the rewards are immeasurable. It’s a review of a profound way of seeing, a method that transforms every landscape into a rich tapestry of stories, wisdom, and enduring human connection.

By learning to use Native American maps for research and travel, we don’t just find new routes; we discover new ways of being in the world, fostering a deeper respect for indigenous sovereignty, cultural heritage, and the living earth itself. This is a journey worth taking, a map worth learning, and an experience that will redefine your understanding of place, forever.