Tracing Ancient Footprints: Navigating the Finger Lakes Through Northeastern Native American Tribal Maps

Forget the glossy brochures and curated itineraries for a moment. Imagine, instead, your travel guide isn’t a modern GPS but an invisible overlay of ancient pathways, ancestral hunting grounds, and vibrant villages that once thrived across the land you traverse. This isn’t about finding dusty old paper maps; it’s about understanding the deep, enduring cartography etched into the very landscape by the Indigenous nations of the Northeastern Woodlands. For the discerning traveler seeking a profound connection to place, exploring a region like New York’s Finger Lakes through the lens of Northeastern Native American tribal maps offers an unparalleled journey into history, culture, and the spirit of the land.

The Finger Lakes region, with its eleven long, slender lakes resembling the fingers of a hand, was and remains the ancestral homeland of the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Confederacy, primarily the Seneca and Cayuga Nations. Before European contact, their "maps" weren’t drawn on parchment but lived in oral traditions, mnemonic devices, and an intimate, experiential knowledge of the land itself. Every hill, river bend, forest grove, and lake shore held significance – a hunting ground, a sacred site, a village location, a trade route. To travel here with this awareness is to embark on a quest not just to see sights, but to feel the echoes of a profound human history.

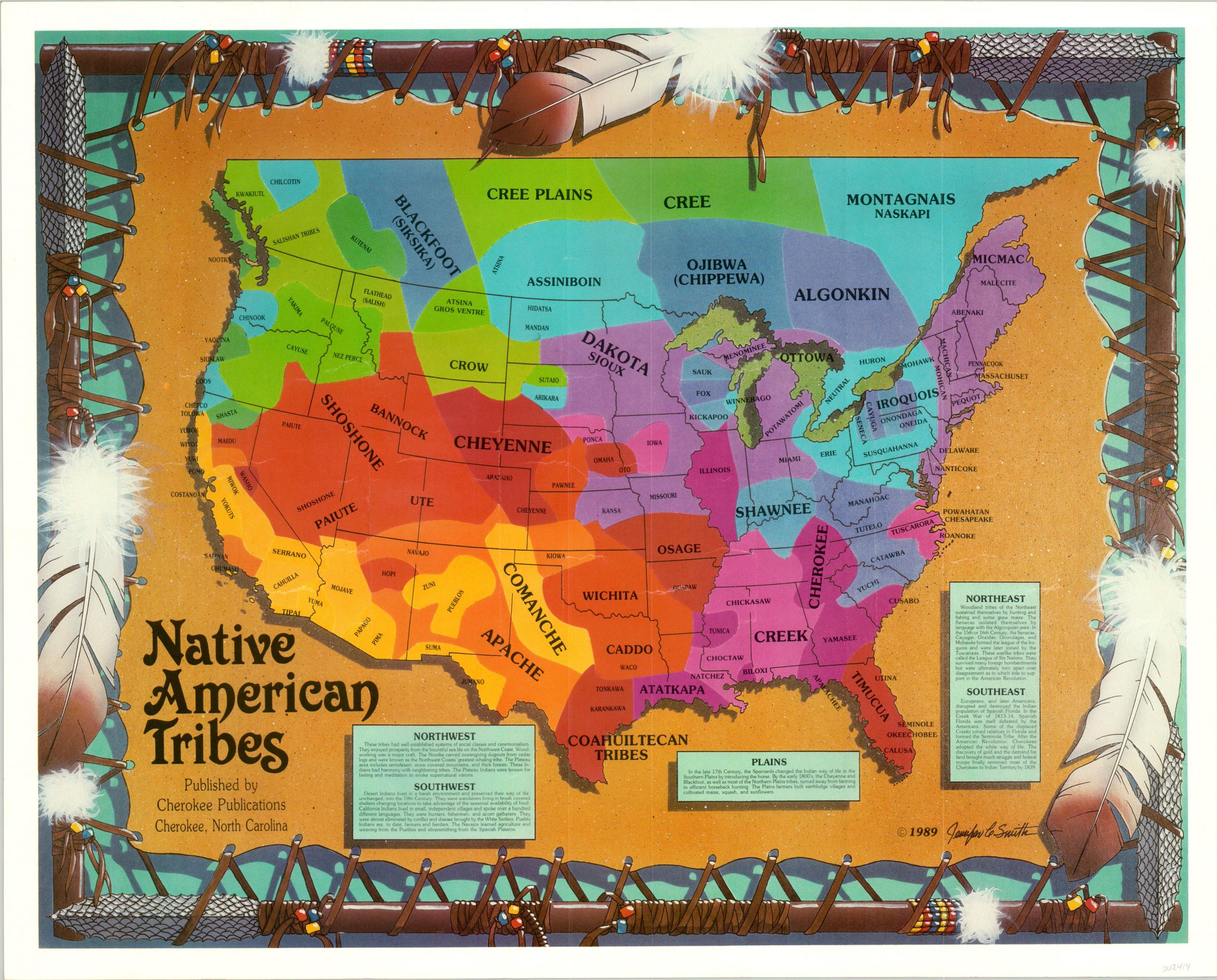

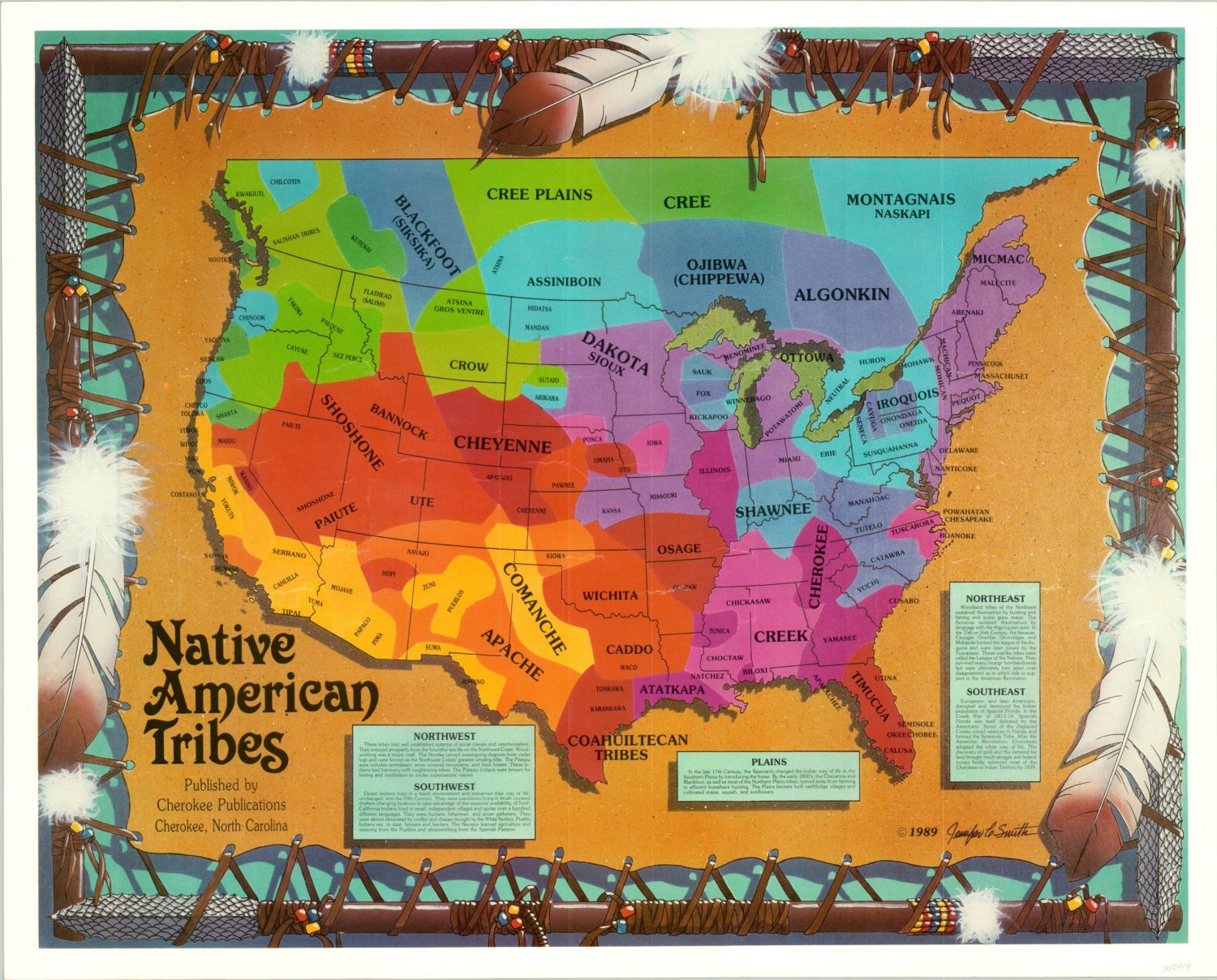

Our journey begins by understanding the foundational "map" of the Haudenosaunee. The Great Law of Peace bound together the Seneca, Cayuga, Onondaga, Oneida, and Mohawk Nations (later joined by the Tuscarora). Their territories stretched across what is now New York, and the Finger Lakes formed the heartland of the Seneca, "Keepers of the Western Door," and the Cayuga, nestled between their larger neighbors. These weren’t arbitrary lines on a map; they were living territories defined by kinship, resource management, and strategic defense. The lakes themselves were central arteries, not just features on a map, providing sustenance, transportation, and spiritual grounding.

So, how does a modern traveler engage with these ancient, unwritten maps? It means shifting your perception from viewing the landscape as merely scenic to understanding it as a palimpsest of human endeavor and ecological wisdom. Your itinerary becomes less about ticking off attractions and more about immersing yourself in the types of locations that would have been vital to the Haudenosaunee:

Ganondagan State Historic Site: Mapping a Living Village

No exploration of Seneca territory is complete without a visit to Ganondagan State Historic Site in Victor, New York. This is arguably the most tangible and immersive "map" you will encounter. Ganondagan was a thriving 17th-century Seneca town, encompassing longhouses, agricultural fields, and a sophisticated social structure. It was one of the largest Seneca settlements, a strategic hub for trade and defense, tragically destroyed in 1687 by French forces.

Today, Ganondagan isn’t just a historical marker; it’s a vibrant interpretive center that brings the Seneca world to life. The full-size replica of a 17th-century Seneca longhouse immediately transports you. Stepping inside, you can almost hear the voices, smell the smoke from the hearths, and imagine the multi-generational families who lived, worked, and governed within its communal walls. This longhouse is a living map of Seneca community, architecture, and daily life. The trails that wind through the site lead you through former cornfields, past mounds marking previous longhouse locations, and offer panoramic views of the surrounding landscape – views that Seneca villagers would have shared. The Interpretive Center provides invaluable context, showcasing artifacts, explaining the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, and detailing the Seneca relationship with the land. Ganondagan is not just a place to learn; it’s a place to feel the vibrant presence of a civilization that once flourished, offering a direct spatial understanding of what a Seneca "village map" truly entailed.

Letchworth State Park: Tracing Ancient Corridors

Further west, where the Genesee River carves a dramatic gorge through the landscape, lies Letchworth State Park, often called the "Grand Canyon of the East." While renowned for its breathtaking waterfalls and deep canyons, Letchworth’s significance extends far beyond its geological wonders when viewed through a Native American lens. The Genesee River was a vital corridor, a major artery on the Seneca’s mental map of their territory. It was a source of fish, a pathway for canoes, and its fertile banks supported settlements and hunting grounds.

Hiking the trails along the gorge, you are, in essence, walking ancient paths. Imagine the Seneca navigating these same bluffs, hunting in the forests, and camping by the river. The high ground offered strategic lookouts, while the river itself connected distant communities. A visit to the Seneca Council House within the park, though moved from its original location, provides another tangible link to the political and social mapping of the Haudenosaunee. Understanding the river’s role as a lifeline and a boundary transforms your experience of this stunning natural landscape. It ceases to be just a beautiful park and becomes a segment of a vast, living map.

The Lakes Themselves: Waterways as Central Features

The Finger Lakes themselves – Seneca, Cayuga, Canandaigua, Keuka, Owasco, Skaneateles, and others – are the most prominent features on any Indigenous map of the region. These weren’t merely bodies of water; they were the heart of existence. For the Cayuga Nation, Cayuga Lake was the defining feature of their territory, while Seneca Lake held similar centrality for the Seneca.

Consider a kayaking or paddleboarding excursion on one of these lakes. As your paddle dips into the water, you’re not just enjoying recreation; you’re traveling a route that countless Indigenous ancestors traversed for millennia. Imagine their dugout canoes laden with corn, furs, or trade goods. The shores were dotted with fishing camps, sacred sites, and temporary settlements. The depths provided fish, and the surrounding lands offered game and medicinal plants. When you stand on a bluff overlooking Seneca Lake, stretching for over 38 miles, try to visualize it not as a modern recreational playground, but as a vast, interconnected system of life, a primary resource and communication network on the Haudenosaunee map. The longhouse villages, like Ganondagan, were strategically located to access these waterways, illustrating the sophisticated geographical understanding that guided their settlement patterns.

Montezuma National Wildlife Refuge: Mapping Resource-Rich Landscapes

At the northern end of Cayuga Lake lies the Montezuma National Wildlife Refuge, a vast expanse of wetlands, marshes, and waterways. Today, it’s a haven for migratory birds, but historically, it was an incredibly rich resource area for the Cayuga and other Haudenosaunee nations. This kind of landscape would have been meticulously mapped in their minds, denoting prime hunting and fishing grounds, areas for gathering wild rice, reeds for baskets, and medicinal plants.

Exploring the refuge’s trails and observation decks allows you to connect with a different kind of "map" – a resource map. It highlights how Indigenous communities understood and managed their environment for sustenance and survival. The abundance of wildlife here is a testament to the ecological knowledge and stewardship practiced by the original inhabitants. It’s a powerful reminder that their maps weren’t just about where to live, but where to thrive, where to gather, and where to maintain the delicate balance of the natural world.

Beyond the Sites: The Feeling of the Land

Engaging with the Finger Lakes through this historical lens isn’t just about visiting specific sites; it’s about a fundamental shift in perception. As you drive through rolling hills, hike through dense forests, or stand on a quiet shore, the land itself begins to speak. The ancient trails, now often paved over or transformed into modern roads, still hint at the lines of communication that once connected communities. The fertile soils, still producing bountiful harvests, echo the intensive agricultural practices of the Haudenosaunee, whose "Three Sisters" (corn, beans, and squash) formed the bedrock of their diet and culture.

This interpretive mapping encourages a deeper sense of presence and respect. It’s an acknowledgment that this land was not "discovered" but has been lived upon, nurtured, and mapped by Indigenous peoples for thousands of years. The challenges, of course, are immense. Centuries of colonization, displacement, and the deliberate erasure of Indigenous history mean that many physical markers are gone. The "maps" we seek are often intellectual, spiritual, and interpretive, requiring an active imagination and a commitment to learning. It’s crucial to acknowledge the ongoing presence of the Haudenosaunee nations today and to understand that their connection to these lands is enduring. Support contemporary Indigenous cultural centers or artists when possible, and approach the history with sensitivity and respect.

Practical Travel Tips for the Conscious Explorer:

- Research Extensively: Before you go, delve into the history of the Seneca and Cayuga Nations. Resources from Ganondagan, university archives, and tribal websites are invaluable.

- Visit Interpretive Centers: Places like Ganondagan are essential for providing context and understanding.

- Hike and Paddle: Get out onto the land and water. This is the best way to feel the ancient pathways and waterways.

- Seek Local Knowledge: Smaller local historical societies might have specific information on Indigenous presence in their immediate area.

- Respect the Land: Practice Leave No Trace principles. Understand that you are a guest on ancestral lands.

- Look for Contemporary Connections: While the focus is historical, remember that Indigenous peoples are still here. Seek out opportunities to learn about contemporary Haudenosaunee culture and challenges, always with respect and appropriate engagement.

In conclusion, a journey through the Finger Lakes region guided by the invisible, yet profoundly felt, maps of the Northeastern Native American tribes is more than just a vacation; it’s an act of historical re-engagement. It transforms the familiar into the sacred, the scenic into the significant. It’s an invitation to travel not just across space, but across time, to understand the deep, layered history of a land that continues to bear the indelible imprint of its first inhabitants. By consciously seeking out the echoes of these ancient maps, we don’t just see the Finger Lakes; we begin to truly understand them, fostering a richer, more meaningful connection to this remarkable corner of the world.