Beyond the Reservation: Unpacking the Map of Native American Urban Life

The mental image of Native American life often conjures vast plains, sacred mountains, or remote reservations. While these landscapes remain central to the identity and sovereignty of many Indigenous nations, they represent only a part of a much larger, more complex story. Today, over 70% of Native Americans live in urban areas, a demographic shift that has profoundly reshaped Indigenous identity, community, and political power. A map depicting Native American urban populations tells a story not just of migration, but of resilience, adaptation, and the enduring spirit of diverse peoples in the face of centuries of systemic disruption.

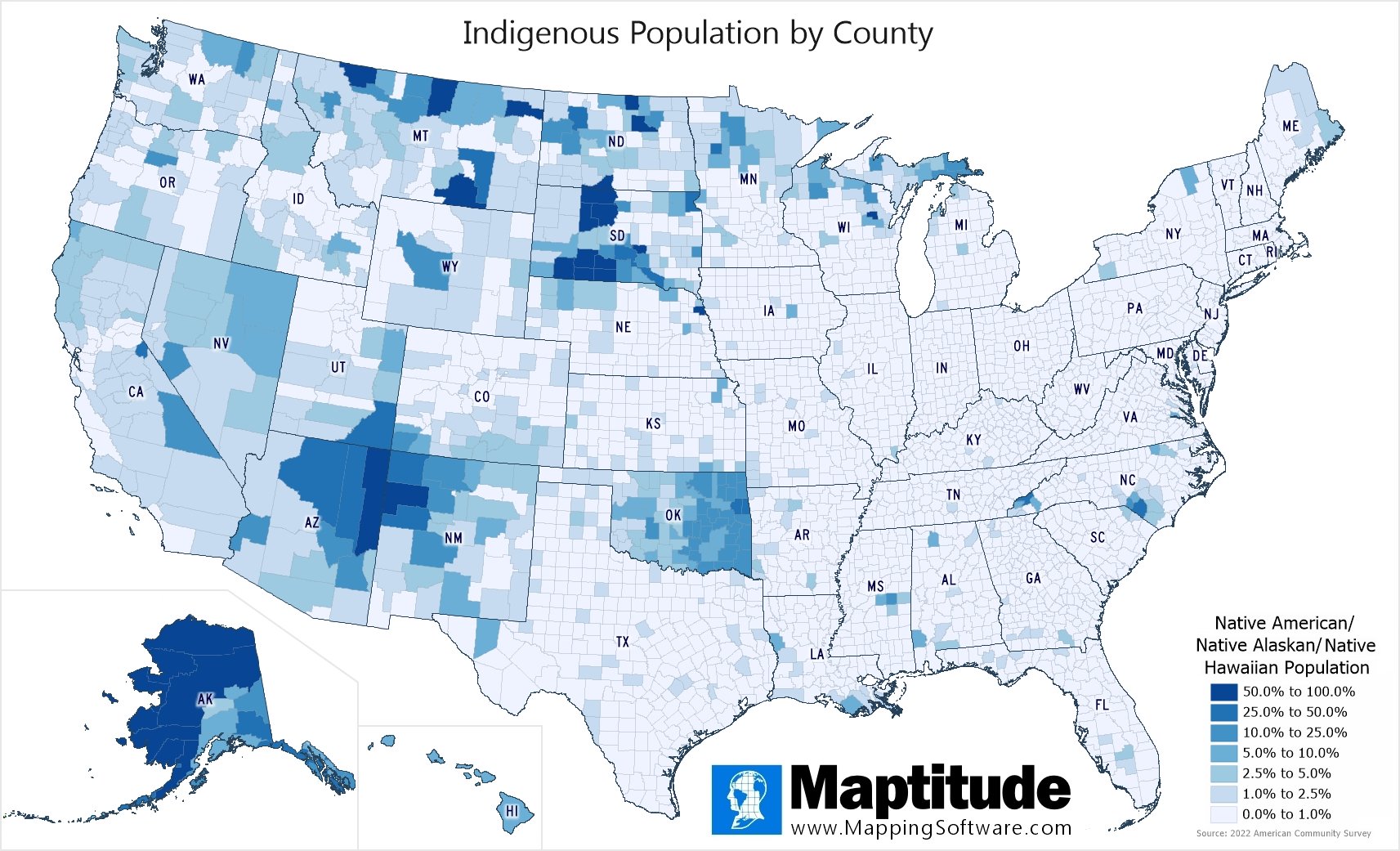

This map is not merely a scattering of dots; it is a vibrant tapestry woven from historical policies, economic realities, and an unwavering commitment to cultural survival. It reveals significant concentrations of Indigenous peoples in major metropolitan centers across the United States, from Los Angeles and Phoenix in the Southwest to Minneapolis and Chicago in the Midwest, and even unexpected hubs like New York City and Seattle. Understanding this map requires delving into the historical forces that shaped it and appreciating the unique ways Indigenous identity thrives within these urban landscapes.

The Historical Undercurrents: Why the Map Looks This Way

The present-day distribution of Native American urban populations is a direct consequence of a series of deliberate, often coercive, U.S. government policies aimed at assimilation and dispossession. While Indigenous peoples have always moved, traded, and established communities in diverse settings, the mid-20th century saw a dramatic acceleration of urban migration.

Pre-Colonial Urbanism: It’s crucial to first dispel the myth that Indigenous peoples were solely nomadic or rural. Pre-contact North America boasted sophisticated urban centers like Cahokia (near modern-day St. Louis), a sprawling metropolis that rivaled European cities in size and complexity, and the Ancestral Puebloan cliff dwellings. These were vibrant hubs of trade, culture, and governance, demonstrating an ancient capacity for urban living long before European arrival. The current map, therefore, is not an entirely new phenomenon but a contemporary expression of an ancient adaptability, albeit under vastly different circumstances.

The Era of Forced Relocation (1950s-1970s): The most significant driver of modern Native American urbanization was the Indian Relocation Act of 1956, part of a broader federal policy known as "Termination." The U.S. government, through the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), sought to dismantle tribal governments, abolish reservations, and assimilate Native Americans into mainstream American society. The Relocation Program specifically encouraged and funded the migration of Native Americans from reservations to major cities like Los Angeles, Chicago, Denver, and Cleveland.

The promise was of better jobs, education, and housing. The reality was often harsh: participants frequently arrived in cities with inadequate support, facing discrimination, poverty, and a profound cultural disconnect. The program’s explicit goal was to break tribal ties and dissolve Indigenous communities. Ironically, it had an unintended, powerful counter-effect: it fostered the creation of new, intertribal communities in urban centers. Separated from their specific tribal lands and traditions, Indigenous individuals from diverse nations found common ground, forging a shared "pan-Indian" identity and building new support networks.

Economic Opportunities and Educational Pursuits: Beyond government policy, economic realities played a significant role. Reservations, often resource-poor due to historical land theft and underinvestment, frequently lacked sufficient job opportunities. Cities, conversely, offered the allure of employment, higher wages, and access to advanced education. Many young Native Americans moved to urban centers to pursue degrees or vocational training unavailable on their home lands, intending to return but often finding themselves establishing new lives.

Self-Determination and the Return to Cities: The era of Termination officially ended in the 1970s with the rise of the Self-Determination policy, which recognized tribal sovereignty and supported tribal self-governance. While this shift allowed for the revitalization of reservation communities, the urban populations had already become established. Many urban Indians, now empowered by a pan-Indian consciousness, began organizing to advocate for their rights and cultural needs within the cities, leading to the establishment of crucial urban Indian centers and services.

Interpreting the Map: What the Data Reveals

A map of Native American urban populations doesn’t just show numbers; it illustrates patterns of migration, networks of community, and cultural hotspots.

Major Urban Hubs:

- Los Angeles, CA: Often called the "largest reservation in the U.S.," Los Angeles boasts one of the highest Native American populations, drawing people from the Southwest (Navajo, Apache, Hopi, Zuni) and Plains tribes (Lakota, Cheyenne) due to its historical role as a primary relocation destination and its vast job market.

- Phoenix, AZ: Proximity to numerous tribal lands in Arizona and New Mexico makes Phoenix a natural magnet, with large populations of Navajo, Apache, Pima, and Maricopa people.

- Oklahoma City and Tulsa, OK: Oklahoma is home to 39 federally recognized tribes, and its major cities reflect this diversity, with a strong presence of Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole people, many of whom were forcibly removed to Indian Territory in the 19th century.

- Minneapolis-St. Paul, MN: This region is a significant hub for Ojibwe (Anishinaabe) and Dakota (Sioux) communities, due to proximity to reservations and historical connections.

- Seattle, WA: Draws Indigenous peoples from various Northwest tribes, Alaska Native communities, and other regions due to its strong economy and historical relocation efforts.

- Denver, CO: Another relocation hub, Denver has a diverse intertribal population, including many from the Plains and Southwest.

- Chicago, IL: As a major industrial center, Chicago attracted many Indigenous individuals during the relocation era, particularly from the Great Lakes region and the Plains.

- New York City, NY: While not as geographically concentrated as some Western cities, NYC has a vibrant and diverse Indigenous presence, including a significant population of Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) people, many of whom historically worked on high steel construction.

Density vs. Diversity: The map highlights not just where Native Americans live, but the incredible diversity within these urban spaces. Unlike reservations, which are often tribally specific, urban centers are melting pots where dozens, sometimes hundreds, of different tribal nations converge. This intertribal dynamic is a defining feature of urban Indigenous identity, fostering a rich exchange of traditions, languages, and perspectives.

Growth and Reverse Migration: The trend towards urbanization continues, but the map also hints at a more complex flow. While cities offer opportunities, the desire to reconnect with ancestral lands, participate in tribal governance, or escape urban challenges has also led to "reverse migration," where some Indigenous individuals and families move back to reservations or rural tribal communities. This dynamic ebb and flow further complicates and enriches the story the map tells.

Identity in the Concrete Jungle: Reclaiming and Redefining

For many Indigenous individuals, moving to an urban area presents a unique challenge: how to maintain a strong cultural identity when separated from ancestral lands, extended family networks, and traditional ceremonies. Yet, the map demonstrates that urban settings are not places where Indigenous identity fades, but where it adapts, re-forms, and often flourishes in new and powerful ways.

The Rise of Pan-Indianism: In cities, the specific traditions of individual tribes often merge into a broader "pan-Indian" identity. This shared experience of being Indigenous in a non-Indigenous dominant society fosters solidarity and a common cultural framework. Urban powwows, for instance, are rarely tribally specific; they are intertribal gatherings where people from many nations come together to dance, sing, and celebrate their shared heritage. This phenomenon is a testament to the resilience and adaptability of Indigenous cultures.

Urban Native American Centers: Crucial to this cultural survival are the numerous urban Native American centers. These organizations, often established by Indigenous activists and community leaders, serve as lifelines. They provide vital social services (housing assistance, healthcare, job training), cultural programming (language classes, traditional arts workshops, drumming circles), and a safe space for community gathering. They are the physical embodiments of the dots on the map, transforming mere population figures into living, breathing communities.

Cultural Revitalization: Far from being lost, Indigenous cultures in urban settings are often undergoing revitalization. Language immersion programs, traditional art forms, storytelling, and ceremonial practices are being consciously preserved and taught to younger generations. Urban Indigenous youth, often blending traditional knowledge with contemporary urban experiences, are at the forefront of this revitalization, utilizing social media and modern art to express their unique identities.

Political and Social Activism: Urban centers have historically been crucial sites for Indigenous activism. The American Indian Movement (AIM) was founded in Minneapolis, and many significant protests and movements have originated in or drawn strength from urban Indigenous communities. The map, therefore, also signifies centers of political organizing and advocacy, where Indigenous voices collectively demand justice, recognition, and sovereignty.

For the Traveler and Learner: Engaging with Urban Native Culture

For those interested in understanding the full breadth of Native American life, exploring the Indigenous presence in urban centers is essential. This is not about seeking out "authentic" experiences in a superficial way, but about respectful engagement with living, evolving cultures.

Beyond Stereotypes: The first step is to discard romanticized or stereotypical notions of Native Americans. Urban Indigenous people are doctors, artists, entrepreneurs, activists, and everyday citizens, blending their Indigenous heritage with modern life. They are not relics of the past but vibrant contributors to contemporary society.

Where to Look:

- Urban Native American Centers: These are the best starting points. Many centers welcome visitors and offer public events, cultural workshops, and opportunities to learn directly from community members.

- Museums and Cultural Institutions: Seek out museums that have strong Native American exhibits, particularly those developed in collaboration with Indigenous communities or that employ Indigenous curators. Examples include the National Museum of the American Indian (though primarily in D.C. and NYC, its influence is broad), and regional museums in cities like Phoenix, Denver, or Seattle.

- Powwows: Attending a public powwow is an immersive experience. These gatherings are vibrant celebrations of dance, music, and community. Research local listings for "urban powwows" in major cities. Remember to observe proper etiquette, such as asking before taking photos and respecting sacred areas.

- Native-Owned Businesses and Art Galleries: Support Indigenous entrepreneurs, artists, and restaurants. This directly contributes to the economic well-being of the community and offers authentic cultural insights.

- Community Events: Look for public lectures, film screenings, art shows, or educational programs organized by Indigenous groups in urban areas.

Respectful Engagement: Approach these experiences with an open mind, a willingness to listen, and profound respect. Recognize that you are a guest. Learn about the specific Indigenous histories of the land you are visiting, even in a city. Support Indigenous self-determination and cultural preservation efforts.

Conclusion

The map of Native American urban populations is a powerful counter-narrative to historical attempts at erasure. It illustrates not a displacement into anonymity, but a profound transformation and reassertion of identity. These urban centers, once intended as melting pots for assimilation, have instead become crucibles for the forging of new, dynamic Indigenous communities.

For travelers and learners, this map points to a rich, often overlooked, dimension of American history and contemporary culture. It invites us to look beyond the expected, to challenge preconceived notions, and to discover the vibrant, resilient, and diverse Indigenous nations thriving in the heart of our cities. To truly understand Native America is to understand that its heartbeat echoes not just across vast plains and sacred mountains, but also along the bustling streets and within the close-knit communities of its urban centers.