The Unseen Map: Navigating the Diverse Justice Systems of Native America

When we speak of a "Map of Native American justice systems," we aren’t referring to a single, static cartographic representation. Instead, we are exploring a vast, intricate, and living mosaic of legal frameworks, each a testament to the enduring sovereignty, distinct cultures, and profound resilience of hundreds of Native American nations across the United States. This conceptual map reveals not just legal procedures, but the very heart of identity, history, and self-governance for Indigenous peoples – a crucial understanding for anyone seeking a deeper appreciation of America’s true landscape.

The Deep Roots: Justice Before Contact

Before European arrival, North America was a continent of complex societies, each with sophisticated and highly contextualized systems of justice. These pre-colonial frameworks were not based on the punitive, retributive models that would later dominate Western law. Instead, they were deeply embedded in community values, spiritual beliefs, and the maintenance of harmony. Justice was often restorative, focusing on healing the individual, repairing harm to the community, and re-establishing balance.

For the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Confederacy, the Great Law of Peace established a complex constitutional system governing inter-tribal relations and internal disputes, emphasizing consensus and diplomacy. Among the Navajo (Diné), the concept of Hózhó – balance and harmony – guided peacemaking councils where elders facilitated dialogue to resolve conflicts, often through reparations and reconciliation rather than punishment. The Cheyenne, Lakota, and other Plains tribes relied on warrior societies and tribal councils to enforce norms, with shaming and banishment being potent tools for maintaining social order. These diverse systems, while unique to each nation, shared common threads: an emphasis on collective well-being, the wisdom of elders, spiritual guidance, and a deep understanding of human interconnectedness. They were expressions of sovereignty long before the term was coined in a European context.

The Collision of Worlds: Colonialism and Its Aftermath

The arrival of European powers initiated a centuries-long assault on Indigenous sovereignty and, by extension, their justice systems. Colonial powers, and later the United States, viewed Native legal traditions as "primitive" or non-existent, imposing their own laws and administrative structures. Treaties, often broken or coerced, became the primary legal instruments governing relations, but these were frequently interpreted unilaterally by the U.S. government to dispossess tribes of land and power.

The 19th century brought the era of "Indian Removal," epitomized by the Trail of Tears, where tribes like the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole, despite having their own written constitutions and courts, were forcibly relocated. The Supreme Court cases of Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (1831) and Worcester v. Georgia (1832) established tribes as "domestic dependent nations" – a legal oxymoron that simultaneously recognized their distinct status while subordinating them to federal authority.

Later policies like the Dawes Act of 1887 aimed at forced assimilation by breaking up communal landholdings and imposing individual property ownership, further eroding tribal governance. The federal government also took control of criminal jurisdiction over major crimes in Indian Country through the Major Crimes Act of 1885, a direct response to the Supreme Court’s decision in Ex parte Crow Dog (1883), which affirmed tribal jurisdiction over crimes committed by tribal members on tribal land. This act marked a significant federal intrusion into tribal legal affairs and remains a cornerstone of federal Indian law today.

The Long Road to Self-Determination

The mid-20th century saw a shift in federal Indian policy, albeit a rocky one. The Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 attempted to reverse some of the damage of allotment, encouraging tribes to adopt written constitutions and establish formal tribal governments and courts. However, many of these "reorganized" governments were modeled after Western structures, sometimes at the expense of traditional governance.

The period of "termination" in the 1950s and 60s, aimed at ending federal recognition of tribes and their unique relationship with the U.S., was devastating. Public Law 280 (1953) granted some states broad criminal and civil jurisdiction over certain tribal lands, further complicating the jurisdictional landscape and undermining tribal self-governance.

The tide began to turn with the "self-determination era" starting in the 1970s. Key legislation like the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975 allowed tribes to contract with the federal government to administer their own programs, including justice services. The Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) of 1978 affirmed tribal jurisdiction over child custody proceedings involving Native children, recognizing the importance of maintaining tribal family structures. These acts, alongside countless tribal efforts, began the arduous process of rebuilding and revitalizing Indigenous justice systems.

Mapping the Present: A Mosaic of Modern Tribal Justice

Today, the "Map of Native American justice systems" reveals a dynamic and incredibly diverse landscape. There are 574 federally recognized tribes in the United States, and each is a sovereign nation with the inherent right to govern itself, including establishing and enforcing its own laws. This means there are at least 574 unique justice systems, ranging from highly formalized courts with written codes and trained legal professionals to traditional peacemaking councils rooted in ancient customs.

Components of Tribal Justice Systems:

- Tribal Courts: These are the heart of many tribal justice systems. They handle a wide array of cases, from civil disputes (family law, property, contracts) to criminal misdemeanors. Judges may be elected, appointed, or selected based on traditional criteria. Many tribal courts operate under codes that blend elements of Anglo-American law with traditional tribal laws and customs.

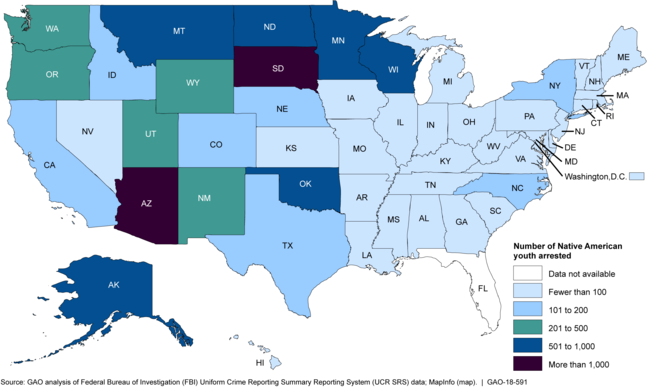

- Law Enforcement: Over 200 tribes operate their own police departments, providing vital public safety services on their lands. These officers are often cross-deputized by state or federal agencies, allowing them to enforce a broader range of laws.

- Correctional Facilities: Some tribes operate their own jails or detention centers, while others contract with federal, state, or county facilities.

- Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR): Many tribes actively integrate traditional ADR methods, such as peacemaking, talking circles, and mediation, which emphasize reconciliation, healing, and community involvement over adversarial proceedings. These approaches are often more culturally appropriate and effective for Native communities.

- Prosecution and Defense: Tribal nations employ their own prosecutors and public defenders or contract for these services, ensuring due process within their systems.

The Complexities of Jurisdiction:

One of the most challenging aspects of this "map" is understanding the intricate web of jurisdictional authority in Indian Country. Who has the power to investigate, arrest, prosecute, and punish for a crime? It depends on:

- Where the crime occurred: On tribal land, state land, or federal land?

- Who committed the crime: A tribal member, a non-member Indian, or a non-Indian?

- What type of crime it is: A major felony, a misdemeanor, or a civil matter?

The Supreme Court’s decision in Oliphant v. Suquamish Indian Tribe (1978) significantly limited tribal criminal jurisdiction, holding that tribes generally do not have inherent criminal jurisdiction over non-Indians. This created a dangerous "jurisdictional gap," especially on reservations, where non-Native perpetrators of crimes against Native people often faced no justice, as state authorities frequently claimed no jurisdiction and federal authorities were selective in their prosecution.

Later legislation and court decisions have attempted to address these gaps. The Tribal Law and Order Act (TLOA) of 2010 enhanced tribal sentencing authority and improved data collection. The Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) reauthorization of 2013, and expanded in 2022, restored some special criminal jurisdiction to tribes over non-Indian perpetrators of domestic violence, dating violence, sexual assault, and other crimes committed in Indian Country. While these are significant steps, the jurisdictional landscape remains incredibly complex and often underfunded, posing ongoing challenges to justice for Native communities.

Justice as Identity: Sovereignty in Action

The revitalization of Native American justice systems is far more than a legal endeavor; it is a profound act of cultural reclamation and an assertion of inherent sovereignty. For many tribes, operating their own courts and law enforcement is a direct manifestation of their nationhood and their right to self-governance. It allows them to:

- Preserve Cultural Values: Integrate traditional legal principles, ethical frameworks, and dispute resolution methods into contemporary practice. This ensures that justice is administered in a way that respects and reinforces tribal identity.

- Heal Historical Trauma: Provide a forum for justice that acknowledges the impact of generations of colonial oppression, fostering healing within the community.

- Promote Community Well-being: Address crime and conflict in ways that are tailored to the specific needs and social structures of the community, often prioritizing rehabilitation and reintegration over simple punishment.

- Strengthen Self-Governance: Develop and exercise the governmental capacity necessary to protect their citizens and resources, and to shape their own futures.

Challenges and Triumphs: The Ongoing Journey

Despite significant progress, tribal justice systems face numerous challenges: chronic underfunding, jurisdictional complexities that lead to gaps in justice, a shortage of culturally competent legal professionals, and the ongoing impact of historical trauma on their communities. Yet, the triumphs are equally profound. Tribes are continuously innovating, adapting, and strengthening their justice systems, demonstrating remarkable resilience and determination. They are building robust legal infrastructures, training their own judges and police officers, and developing unique programs that reflect their distinct cultural values.

Beyond the Map: Why This Matters for Travelers and Learners

For anyone traveling through or learning about the United States, understanding this "Map of Native American justice systems" is not just an academic exercise; it is essential for respectful engagement and a complete understanding of the nation.

- Respect Sovereignty: Recognizing that tribal nations are distinct governmental entities with their own laws is fundamental to respecting their sovereignty. When you visit tribal lands, you are entering a different nation with its own rules and customs.

- Appreciate Diversity: This conceptual map highlights the incredible diversity of Indigenous cultures and governance structures, moving beyond monolithic stereotypes.

- Understand History’s Legacy: The complexities of tribal justice today are a direct result of centuries of interaction with the U.S. government, marked by both oppression and resilience.

- Support Self-Determination: By learning about and advocating for strong tribal justice systems, we support the self-determination and well-being of Native communities.

To truly travel through America is to understand its multifaceted past and present. The "Map of Native American justice systems" offers a crucial lens through which to view the enduring identity, sovereignty, and adaptive strength of Indigenous nations – a living, breathing testament to their rightful place in the ongoing story of this continent. It’s a journey not just across lands, but across cultures, histories, and the very concept of justice itself.