Beyond the Lines: Navigating Southeastern Indigenous Lands with Ancient Maps as Your Guide

Forget everything you think you know about maps. For most of us, a map is a static, two-dimensional representation of a place, drawn with grids and standardized symbols. But for the Indigenous peoples of the American Southeast – the Cherokee, Muscogee (Creek), Choctaw, Chickasaw, Seminole, and countless others – maps were, and often still are, living, breathing narratives. They are stories etched into the landscape itself, sung in ancient languages, passed down through generations, and manifested in the very way communities interacted with their homelands.

This isn’t a review of a single museum exhibit or a specific historical park. Instead, this is an invitation to review an entire region – the ancestral lands of the Southeastern Indigenous peoples – through the profound, often overlooked, lens of their traditional cartography. It’s a journey that redefines "travel" from simply visiting sites to deeply understanding place, guided by a wisdom far older than any European-drawn chart.

The "Place" Under Review: The Ancestral Southeastern Landscape

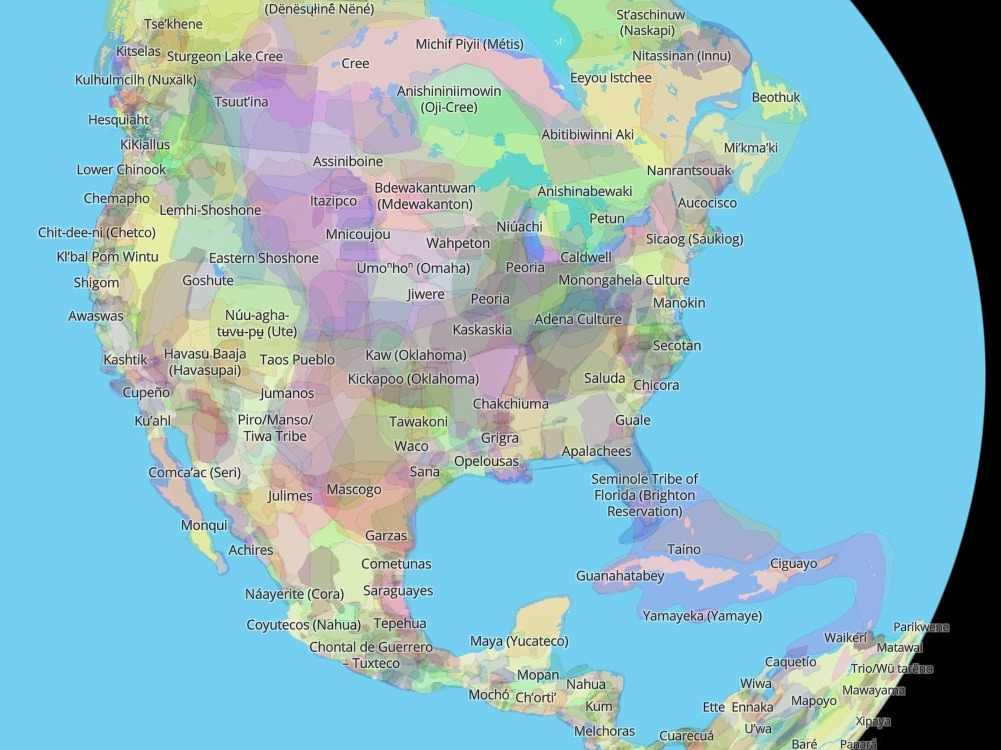

The "place" we’re reviewing is the vast, ecologically diverse tapestry of the Southeastern United States, encompassing modern-day states like Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Florida, Tennessee, North Carolina, South Carolina, Kentucky, and parts of Louisiana and Arkansas. This region, teeming with rivers, mountains, swamps, and fertile plains, was not an empty wilderness but a meticulously understood and managed landscape, crisscrossed by trade routes, marked by sacred sites, and sustained by complex agricultural systems.

To truly review this place through Indigenous maps means to embark on a multi-faceted exploration. It means visiting specific cultural centers and historical sites, yes, but more importantly, it means learning to read the land itself as Indigenous peoples did.

Unpacking Indigenous Cartography: More Than Just Paper

Before diving into specific sites, it’s crucial to understand what Indigenous "maps" entailed. Unlike the paper maps introduced by Europeans, Southeastern Indigenous cartography was often:

- Oral and Performative: Knowledge of routes, resources, boundaries, and historical events was embedded in stories, songs, dances, and ceremonies. These were dynamic, mnemonic devices passed down, ensuring the "map" was never lost, even if physical representations were.

- Environmental and Experiential: The landscape itself was the primary map. Rivers were highways, mountains were landmarks, unique tree formations or rock outcrops marked significant places. The "lines" on these maps were the flow of water, the rise and fall of terrain, the migration patterns of animals.

- Spiritual and Symbolic: Maps often depicted not just physical reality but spiritual connections, sacred sites, and the cosmic order. They were imbued with meaning that went beyond mere navigation.

- Temporary and Contextual: While some physical maps were drawn on hides, bark, or sand for specific purposes (like explaining a journey or a treaty boundary), their ephemeral nature contrasted sharply with European desires for permanent, reproducible charts. The true map lived in the collective memory and experience.

Your Journey: Reading the Land and Its Stories

To review this "place" through an Indigenous cartographic lens, your journey will involve a blend of direct engagement with cultural institutions and mindful exploration of the natural world.

1. The Cherokee Nation: Echoes in the Mountains and Museums

Our journey begins in the heart of the Appalachian Mountains, ancestral home of the Cherokee. The Cherokee Nation, renowned for its sophisticated governance and the development of the syllabary by Sequoyah, had an intricate understanding of their mountainous domain.

- Oconaluftee Indian Village (Cherokee, North Carolina): This living history museum offers an unparalleled glimpse into 18th-century Cherokee life. Here, you’ll see how the landscape dictated architecture, agriculture, and daily routines. Artisans demonstrate traditional crafts, and interpreters share stories. Crucially, pay attention to the flow of the Oconaluftee River, which was a vital artery and boundary. Understanding the river’s role is a fundamental lesson in Cherokee mapping – not as a line on a chart, but as a dynamic pathway.

- Museum of the Cherokee Indian (Cherokee, North Carolina): This world-class museum is essential. Beyond displaying artifacts, it contextualizes them within Cherokee cosmology and history. Look for early maps drawn by European explorers that attempted to delineate Cherokee territory, but more importantly, seek out explanations of how the Cherokee themselves perceived and named their land. You’ll find narratives about sacred places like Kuwahi (Clingmans Dome), not just as a mountain, but as a spiritual nexus.

- New Echota State Historic Site (Calhoun, Georgia): This was the capital of the Cherokee Nation from 1825 until their forced removal. Walking the grounds, you can see the council house, the print shop (where the Cherokee Phoenix newspaper was published), and homes. This site represents a period where the Cherokee were actively asserting their sovereignty and territorial claims against encroaching settlers, often using European-style maps to defend their land in legal battles, while simultaneously maintaining their own profound, internal cartographies. The layout of the town itself, though influenced by American planning, still reflects a deep connection to the local environment and water sources.

2. Muscogee (Creek) Nation: Earthworks as Enduring Maps

Moving west into Georgia, we encounter the ancestral lands of the Muscogee (Creek) people. The Muscogee, a confederacy of various tribes, were master mound builders, and their earthworks serve as some of the most enduring physical "maps" of their spiritual and social organization.

- Ocmulgee Mounds National Historical Park (Macon, Georgia): This park is a revelation. The massive earthen mounds – ceremonial, burial, and defensive – are not random structures. They are deliberate interventions in the landscape, creating sacred spaces and marking significant cosmological alignments. The Great Temple Mound, the Funeral Mound, and the Earth Lodge (with its intricately shaped floor) are tangible representations of Muscogee worldviews. To walk among them is to read a map of their spiritual geography, their societal structure, and their connection to the cosmos. The mounds tell stories of ancestors, ceremonies, and astronomical observations, all embedded in the very earth. The Ocmulgee River, flowing nearby, was another critical "line" on their living map, providing resources and pathways.

3. Choctaw and Chickasaw Homelands: Rivers, Trade, and Enduring Presence

Further west, in Mississippi and Alabama, lie the homelands of the Choctaw and Chickasaw. These nations, deeply connected to the river systems and fertile lands, also had rich traditions of oral and environmental mapping.

- Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians (Philadelphia, Mississippi): While not a historical "site" in the same way as New Echota, visiting the Choctaw reservation offers a crucial perspective: the enduring presence of Indigenous peoples in their ancestral lands. Engage with local cultural events if possible, or visit the Pearl River Community for a sense of contemporary Choctaw life. Their oral traditions and place names continue to map the landscape in ways that modern road signs cannot. Understanding their deep-rooted connection to the land helps contextualize historical maps that depict their vast territories before removal.

- Tupelo, Mississippi (Chickasaw): The Chickasaw lived in what is now northern Mississippi, with Tupelo as a significant area. While specific ancient sites might be less preserved than the Muscogee mounds, understanding the strategic importance of this region – its high ground, fertile soil, and access to waterways – reveals how the Chickasaw effectively "mapped" their defenses and resource management. The Chickasaw Cultural Center in Ada, Oklahoma, while outside the original homelands, offers incredible insights into their history and traditional understanding of their territory, which is vital for understanding their ancestral maps.

4. Seminole Nation: Mapping Resilience in the Everglades

Finally, a distinct journey takes us south to the Florida Everglades, the domain of the Seminole and Miccosukee peoples. Their "maps" are inextricably linked to their incredible resilience and mastery of a challenging environment.

- Big Cypress National Preserve (Ochopee, Florida): Here, the map is the water, the cypress domes, and the hidden hammocks. The Seminole and Miccosukee people were masters of navigating the intricate, ever-changing landscape of the Everglades. Their knowledge of water levels, safe passages, edible plants, and animal behaviors was their map – a constantly updated, experiential cartography that allowed them to survive and resist during the Seminole Wars. Airboat tours, while commercial, can offer a glimpse into the vastness and complexity of the ‘Glades, but deeper understanding comes from learning about traditional dugout canoes and the intimate knowledge required to traverse this unique wetland.

- Ah-Tah-Thi-Ki Museum (Clewiston, Florida): Located on the Big Cypress Seminole Reservation, this museum tells the story of the Seminole people, their adaptation to the Everglades, and their ongoing cultural traditions. You’ll see how their way of life was intrinsically mapped onto the environment, from their chickee houses designed for the climate to their use of specific plants and animals. Their very existence in the Everglades is a testament to their deep, living cartographic knowledge.

The Map of Trauma: The Trail of Tears

No review of Southeastern Indigenous lands and maps can ignore the most tragic "map" of all: the forced removal routes collectively known as the Trail of Tears. This isn’t a map of belonging but of displacement.

- The Trail of Tears National Historic Trail: This designated trail connects various sites across nine states, marking the routes taken by the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Muscogee (Creek), and Seminole during their forced marches to Indian Territory (Oklahoma) in the 1830s. Visiting segments of this trail, such as Mantle Rock Preserve in Kentucky or sections in Tennessee and Georgia, offers a somber but essential understanding of how European colonial maps, driven by land hunger and Manifest Destiny, violently overlaid and erased Indigenous cartographies. It highlights the devastating impact when one culture’s map is imposed upon another’s. This journey is not about finding ancient Indigenous maps, but about understanding the profound loss and the resilience required to navigate a landscape suddenly rendered alien by forced removal.

Practical Considerations for Your Journey

- Respect and Sensitivity: You are visiting ancestral lands and living communities. Be respectful of cultural protocols, private property, and sacred sites.

- Support Indigenous Businesses: Where possible, patronize Indigenous-owned businesses, artists, and cultural programs. Your tourism dollars can directly support these communities.

- Learn Beyond the Tourist Brochure: Seek out books, documentaries, and academic resources that offer Indigenous perspectives on history and land.

- Engage with the Landscape: Take time to walk, observe, and reflect. How does the river flow? What plants grow here? How might this have been understood and utilized by those who lived here for millennia?

Conclusion: A New Way to See the World

Reviewing the ancestral lands of the Southeastern Indigenous peoples through the lens of their traditional maps is not merely a historical exercise; it’s a transformative travel experience. It challenges the conventional wisdom of cartography and invites you to see the world not as a series of static lines and borders, but as a dynamic, interconnected tapestry of stories, spirits, and deep ecological knowledge.

This journey is an invitation to listen to the whispers of the wind through the cypress trees, to feel the history underfoot in the ancient mounds, and to understand that maps are not just about where you are, but who you are, and how you belong to a place. Embark on this journey, and you’ll find that the true map of the Southeast is written not on paper, but in the enduring spirit of its first peoples and the timeless beauty of their cherished homelands. You’ll leave with a profound appreciation for a different way of seeing, a richer understanding of place, and a deeper respect for the living maps that continue to guide us.