Here’s an article directly addressing the Map of Native American Housing Initiatives, suitable for a travel and history education blog, at approximately 1200 words.

>

Beyond the Horizon: Mapping Native American Housing Initiatives – A Tapestry of History, Identity, and Resilience

When we speak of "maps," our minds often conjure images of geographical boundaries, roads, and cities. But imagine a different kind of map – one that charts not just physical locations, but the profound human story embedded within housing. A "Map of Native American Housing Initiatives" is precisely this: a dynamic, living document that reveals centuries of history, the unwavering spirit of cultural identity, and the ongoing journey towards self-determination and well-being for Indigenous peoples across the United States. This isn’t merely about structures; it’s about sovereignty, community, and the right to a home that reflects who you are.

This article delves into what such a conceptual map would illuminate, tracing the historical currents that have shaped Native American housing, exploring the challenges and innovative solutions of today, and celebrating how housing initiatives are intrinsically linked to tribal identity and the assertion of self-governance.

The Conceptual Map: A Mosaic of Needs and Aspirations

At its core, a "Map of Native American Housing Initiatives" would be a comprehensive visualization of the diverse housing landscape within Indigenous communities. It wouldn’t be a single, static image, but rather a layered, interactive experience showcasing:

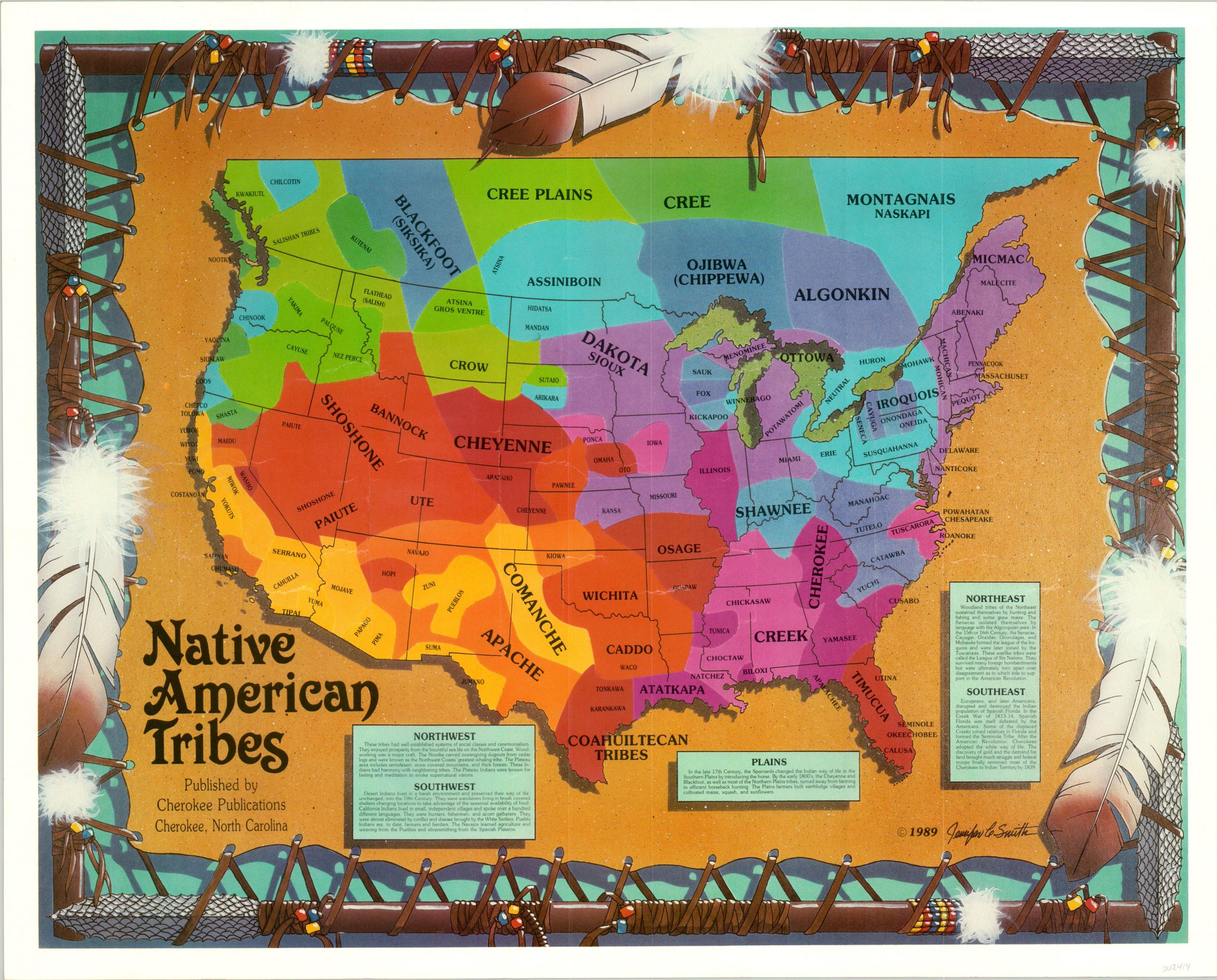

- Geographic Distribution: Where are the federally recognized tribes located? Where are their reservations, and how do they vary in size, climate, and remoteness?

- Housing Stock Data: What is the condition of existing housing? Where are the highest rates of overcrowding, dilapidation, or lack of basic infrastructure (water, sanitation, electricity, internet)?

- Initiative Hotspots: Where are new housing units being built? Where are rehabilitation projects underway? Which communities are implementing unique, culturally sensitive designs?

- Funding Flows: Which federal, tribal, and private programs are supporting these efforts, and where are the needs still unmet?

- Impact Stories: Beyond numbers, the map would point to the human stories of improved health, educational attainment, and economic opportunity that stem from stable, adequate housing.

Such a map quickly disabuses any notion of a monolithic "Native American experience." Instead, it reveals a vibrant, complex mosaic, each tile representing a distinct tribal nation with its own history, challenges, and solutions.

A Legacy of Disruption: The Historical Roots of Housing Challenges

To understand the current state of Native American housing, one must first grasp the profound historical forces that have shaped it. Indigenous housing before European contact was incredibly diverse, sophisticated, and perfectly adapted to varying environments and cultures. From the multi-story adobe pueblos of the Southwest to the longhouses of the Iroquois, the earth lodges of the Plains, and the cedar plank houses of the Pacific Northwest, these structures were not just shelters but embodiments of spiritual beliefs, social structures, and community life. They were sustainable, resilient, and deeply connected to the land.

The arrival of European colonizers shattered this equilibrium. The subsequent policies of the United States government systematically undermined Indigenous ways of life, including housing.

- Forced Removal and Relocation (19th Century): Policies like the Indian Removal Act (1830) violently uprooted tribes from their ancestral lands, forcing them onto unfamiliar territories. This disruption severed ties to traditional building materials, knowledge, and community structures.

- The Reservation System (Mid-19th Century onward): Confining tribes to often desolate, resource-poor reservations further limited their ability to maintain traditional housing. Government-issued, often inadequate, housing replaced culturally appropriate dwellings, leading to initial challenges with overcrowding and substandard conditions.

- Allotment and Assimilation (Dawes Act of 1887): This policy aimed to break up communal tribal landholdings into individual parcels, forcing Indigenous peoples into an Anglo-American model of private property and nuclear family homes. It resulted in the loss of millions of acres of tribal land and further eroded traditional community structures, making it difficult to build or maintain housing collectively.

- Termination and Relocation (1950s-1960s): This era saw the federal government attempt to end its relationship with specific tribes, withdrawing federal services and encouraging Indigenous people to relocate to urban centers. This led to further displacement, a lack of culturally appropriate housing in cities, and exacerbated poverty both on and off reservations.

By the mid-20th century, the legacy of these policies was stark: chronic housing shortages, pervasive substandard conditions, lack of infrastructure, and widespread poverty across Indian Country. This historical context is not merely background; it is the living foundation upon which contemporary housing initiatives are built.

The Dawn of Self-Determination: Modern Housing Initiatives

The shift towards tribal self-determination in the 1970s marked a critical turning point. Recognizing the failures of past paternalistic policies, the federal government began to empower tribes to manage their own affairs, including housing. This culminated in the landmark Native American Housing Assistance and Self-Determination Act (NAHASDA) of 1996.

NAHASDA revolutionized Native American housing by:

- Consolidating Funding: It replaced a patchwork of Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) programs with a single block grant system, giving tribes unprecedented flexibility.

- Empowering Tribes: It transferred control over housing funds and decision-making directly to tribal governments or tribally designated housing entities (TDHEs), often known as Tribal Housing Authorities (THAs). This was a monumental step towards true self-governance.

- Promoting Self-Determination: Tribes could now design and implement housing programs that directly addressed their unique needs, cultures, and priorities, rather than adhering to rigid federal mandates.

Under NAHASDA, Tribal Housing Authorities have become the frontline implementers of housing initiatives. Their work, which would be prominently featured on our conceptual map, includes:

- New Construction: Building homes to alleviate overcrowding and address population growth.

- Rehabilitation: Repairing and upgrading existing substandard housing units.

- Rental Assistance: Providing subsidies to low-income tribal members.

- Homeownership Programs: Creating pathways for tribal members to own their homes, often for the first time.

- Infrastructure Development: Installing essential utilities like water, sewer, and electricity to make new housing viable.

- Housing Management: Operating and maintaining rental units and community facilities.

Beyond NAHASDA, other federal agencies like the USDA Rural Development (for rural home loans and community facilities), the Indian Health Service (for sanitation facilities), and various state and private foundations also contribute to the complex tapestry of housing support.

Housing as an Expression of Identity and Sovereignty

What makes Native American housing initiatives distinct and worthy of deep appreciation is their profound connection to identity and the assertion of sovereignty. On our conceptual map, we wouldn’t just see houses; we’d see homes that embody cultural pride and self-governance.

- Culturally Appropriate Design: Moving beyond generic, Western-style housing, many tribes are now integrating traditional architectural elements, design principles, and spatial arrangements. This might mean incorporating specific orientations for spiritual reasons, using local materials, creating communal spaces reminiscent of traditional gathering areas, or designing homes that accommodate extended families, which is common in many Indigenous cultures. These designs are not mere aesthetics; they are functional expressions of identity, promoting well-being and a sense of belonging.

- Community Building: Housing is not just about individual shelter; it’s about the fabric of a community. Initiatives often include community centers, playgrounds, and shared spaces that foster social cohesion and cultural activities. Stable housing directly impacts health outcomes, educational attainment, and economic development, all vital components of a thriving community.

- Sustainable and Resilient Housing: Drawing upon ancestral knowledge of living in harmony with the land, many tribes are leading the way in sustainable building practices. This includes using passive solar design, natural ventilation, locally sourced materials, and technologies that conserve energy and water. As climate change increasingly impacts tribal lands, building resilient housing that can withstand extreme weather events is becoming a critical aspect of self-determination.

- Asserting Sovereignty: Every housing unit built under tribal authority, every home loan processed by a tribal program, and every community plan developed by a tribal housing board is an act of sovereignty. It demonstrates the capacity of tribal nations to govern themselves, manage their resources, and provide for their citizens. This is nation-building in action, a tangible manifestation of self-determination.

The Future: Continued Innovation and Unfinished Work

The "Map of Native American Housing Initiatives" is far from complete. Significant challenges persist: chronic underfunding, the impacts of climate change on infrastructure, the increasing costs of materials, and the ongoing need for skilled labor in remote areas. Many tribes still face dire overcrowding and lack of basic amenities.

However, the map also highlights incredible innovation and resilience. Tribes are exploring modular housing solutions for rapid deployment, developing their own tribal building codes, creating culturally relevant financial literacy programs, and forging partnerships to leverage resources. They are not just building houses; they are building futures.

For anyone interested in travel, history, or social justice, understanding this conceptual map is essential. It moves beyond superficial narratives, offering a profound appreciation for the diverse cultures, the enduring struggles, and the remarkable triumphs of Native American nations. It invites us to recognize that a home is more than just walls and a roof; it is a repository of history, a beacon of identity, and a testament to the unyielding spirit of a people building their own tomorrow, one home at a time.

As you explore the lands and histories of Native America, remember that every housing initiative, every community development, and every culturally inspired dwelling tells a powerful story – a story of continuity, struggle, and the enduring power of Indigenous identity and self-determination.