Beyond Reservations: Unveiling the Living Map of Native American Tribal Governments

Forget simple lines on a map. To truly understand the landscape of North America, one must look beyond state borders and national parks to the vibrant, complex, and enduring presence of Native American tribal governments. These aren’t merely historical footnotes or cultural curiosities; they are sovereign nations, each with its own history, identity, and unique relationship with federal, state, and even international bodies. For the discerning traveler and history enthusiast, understanding this intricate "map" of governmental relations is not just educational – it’s essential for respectful engagement and a deeper appreciation of a resilient, living heritage.

The Foundation of Sovereignty: A History Forged in Treaties and Resilience

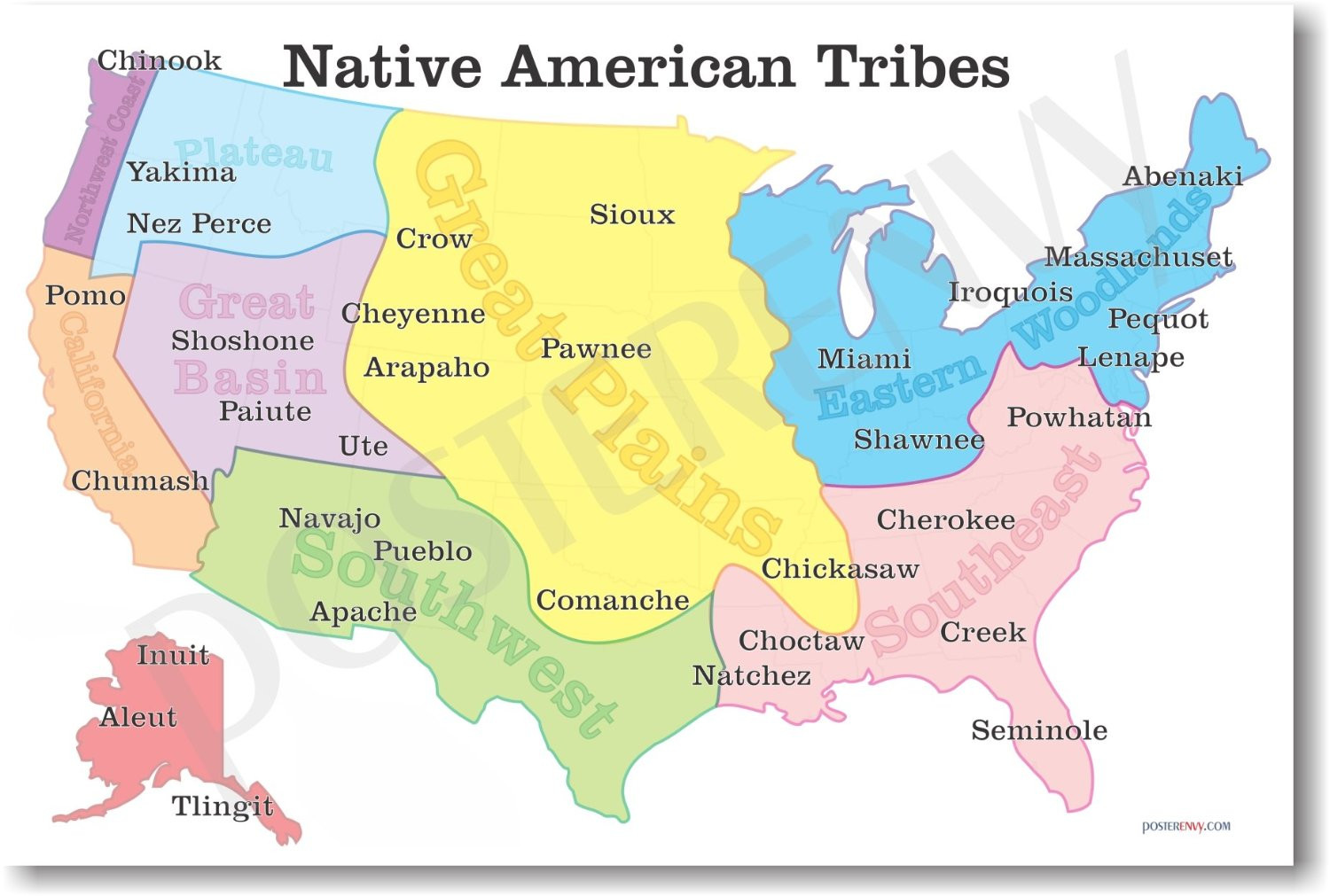

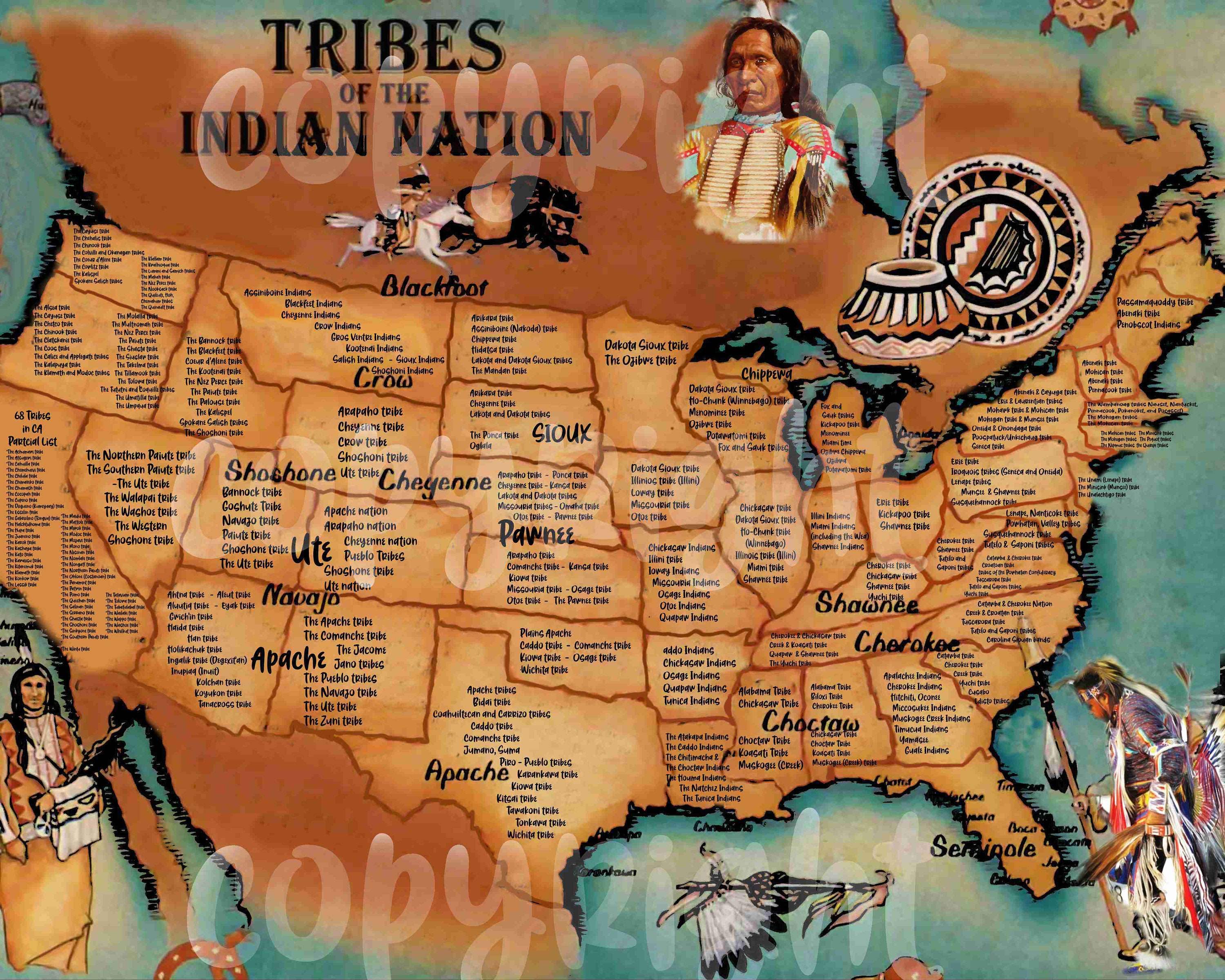

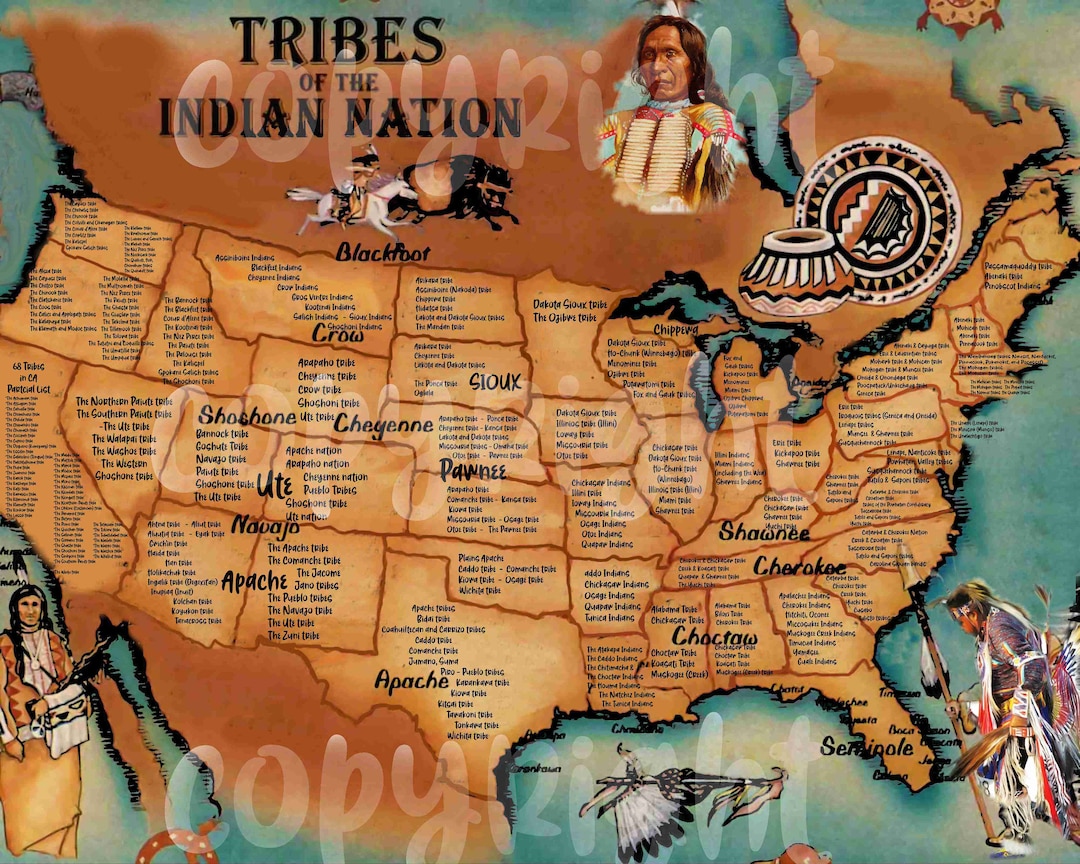

To grasp the current governmental landscape, we must first journey back in time. Prior to European contact, hundreds of distinct Native American nations thrived across the continent, each with sophisticated political systems, economies, and intricate diplomatic networks. These were fully sovereign entities, engaging in trade, warfare, and alliance-making on their own terms.

The arrival of European powers marked a turning point, yet it also solidified the concept of Native sovereignty in a new context. European nations, and later the United States, frequently engaged with tribes through treaties – formal agreements between sovereign powers. While these treaties were often coerced, violated, or misunderstood, their very existence affirmed the status of tribes as independent nations capable of entering into binding agreements.

This principle was enshrined in early U.S. law through the landmark Supreme Court decisions known as the Marshall Trilogy (1823-1832). In Cherokee Nation v. Georgia and Worcester v. Georgia, Chief Justice John Marshall famously described Native American tribes as "domestic dependent nations." This unique legal status, while limiting their foreign policy powers, recognized their inherent sovereignty and distinct governmental authority within their own territories. It established a direct, government-to-government relationship with the U.S. federal government, bypassing state interference. This concept – inherent, but with a unique dependency – remains the cornerstone of federal Indian law today.

A Rollercoaster of Policy: From Removal to Self-Determination

The history of U.S.-tribal relations is a complex tapestry woven with threads of treaty-making, broken promises, and fluctuating federal policies, each profoundly impacting tribal governments and identities:

- The Removal Era (1830s-1850s): Driven by land hunger and expansionism, policies like the Indian Removal Act forcibly relocated Eastern tribes westward, epitomized by the devastating Trail of Tears. This era sought to physically separate tribes, disrupting their traditional governance structures and land bases.

- The Reservation Era (Mid-19th Century): As westward expansion continued, tribes were confined to reservations, often small and unproductive parcels of their ancestral lands. While these lands were held in trust by the federal government, tribal governments often struggled under the paternalistic control of the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), which dictated many aspects of daily life.

- The Allotment and Assimilation Era (1887-1934): The Dawes Act of 1887 aimed to break up tribal communal landholdings into individual parcels, a direct assault on tribal identity and economic systems. The goal was to dismantle tribal governments, assimilate Native Americans into mainstream society, and open "surplus" lands to non-Native settlement. This policy resulted in the loss of two-thirds of tribal lands and immense cultural devastation.

- The Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) Era (1934-1940s): Acknowledging the failures of allotment, the IRA sought to reverse course, encouraging tribes to adopt written constitutions, elect tribal councils, and re-establish their governmental authority. While a step forward, the IRA often imposed Western-style governance models that sometimes clashed with traditional structures, creating internal divisions.

- The Termination and Relocation Era (1950s-1960s): This short-sighted policy aimed to "terminate" federal recognition of tribes, ending their special status and trust relationship, and relocating individuals to urban areas. The results were catastrophic, leading to widespread poverty, loss of land, and severe social dislocation for the terminated tribes.

- The Self-Determination Era (1970s-Present): Beginning with President Nixon, this era marked a profound shift. Federal policy moved towards supporting tribal self-governance, self-sufficiency, and the right of tribes to determine their own futures. Legislation like the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act (1975) allowed tribes to contract directly with the federal government to administer programs previously run by the BIA, from education and healthcare to law enforcement. This era has seen a resurgence of tribal identity, economic development, and governmental capacity.

Mapping the Relationships: A Multi-Layered Governance Landscape

Today, the "map" of Native American local government relations is a complex web involving federal, state, inter-tribal, and local entities.

1. Federal-Tribal Relations: The Government-to-Government Nexus

This is the bedrock relationship. The U.S. federal government recognizes 574 federally recognized tribes as sovereign nations, each with its own government, laws, and jurisdiction over its lands and citizens. This relationship is characterized by:

- Trust Responsibility: The U.S. government has a moral and legal obligation, stemming from treaties and statutes, to protect tribal lands, resources, and self-governance.

- Direct Funding & Services: Federal agencies (BIA, Indian Health Service, Department of Justice) provide funding and services directly to tribes, bypassing state governments.

- Jurisdiction: Tribal courts often have jurisdiction over civil matters and misdemeanor crimes committed by tribal members on tribal land. Federal courts handle major crimes and some civil disputes.

- Consultation: Federal agencies are increasingly required to consult with tribal governments on projects that may impact tribal lands, resources, or cultural sites.

2. State-Tribal Relations: A Landscape of Conflict and Cooperation

While the federal government is the primary interlocutor, state governments often have complex and sometimes contentious relationships with tribes. States generally do not have inherent jurisdiction over tribal lands unless explicitly granted by Congress (e.g., Public Law 280 in some states). This leads to:

- Jurisdictional Disputes: Ongoing conflicts over taxation, law enforcement, environmental regulation, and land use often arise, particularly when tribal lands are surrounded by or adjacent to state jurisdictions.

- Gaming Compacts: The Indian Gaming Regulatory Act (1988) requires tribes to negotiate compacts with states for Class III gaming (casino-style games). These compacts are often a significant source of revenue for both tribes and states.

- Resource Management: Shared concerns over water rights, fishing, hunting, and land management often necessitate intergovernmental agreements.

- Shared Services: Tribes and states increasingly cooperate on issues like emergency management, infrastructure, and public health, recognizing their shared populations and geographical proximity.

3. Inter-Tribal Relations: A Network of Mutual Support and Advocacy

Native American nations do not operate in isolation. A robust network of inter-tribal organizations exists to advocate for shared interests, preserve cultural heritage, and promote economic development:

- National Congress of American Indians (NCAI): The oldest and largest national organization, advocating for tribal sovereignty and well-being at the federal level.

- Regional Organizations: Groups like the United South and Eastern Tribes (USET) or the Great Plains Tribal Chairman’s Association address issues specific to their geographical regions.

- Cultural & Language Initiatives: Tribes collaborate on language revitalization programs, cultural preservation efforts, and educational initiatives.

- Economic Alliances: Tribes form partnerships for joint economic ventures, sharing resources and expertise.

4. Local (County/City)-Tribal Relations: Proximity and Practicalities

At the most immediate level, tribal governments interact with surrounding county and municipal governments on day-to-day issues:

- Infrastructure: Shared roads, utilities, and public services.

- Emergency Services: Mutual aid agreements for fire, police, and medical response.

- Land Use Planning: Coordinating development, zoning, and environmental impact assessments for projects near reservation borders.

- Economic Development: Collaborating on tourism, business parks, and employment opportunities.

Identity and Sovereignty: The Enduring Heart

Underpinning this entire governmental "map" is the profound connection between Native American identity and sovereignty. For Indigenous peoples, sovereignty is not merely a legal concept; it is an inherent right tied to their distinct cultures, languages, spiritual beliefs, and ancestral lands. It is the right to self-determination, to govern themselves according to their own traditions and needs.

Tribal governments today are not just administrative bodies; they are vital institutions that:

- Preserve Culture: Fund language immersion programs, cultural centers, and traditional ceremonies.

- Protect Resources: Manage land, water, and natural resources according to traditional ecological knowledge and modern conservation practices.

- Provide Services: Operate schools, healthcare facilities, police departments, and housing programs tailored to their communities.

- Foster Economic Development: Create jobs, generate revenue (often through gaming, tourism, or resource extraction), and invest in their communities to achieve self-sufficiency.

This resilience, the ability to adapt, survive, and thrive despite centuries of concerted efforts to dismantle their governments and identities, is a testament to the strength of Native American nations.

Engaging Respectfully: A Traveler’s Guide to the Living Map

For the history-minded traveler, understanding this complex governmental landscape is paramount for respectful and enriching experiences. When visiting Native American communities or events:

- Recognize Sovereignty: Understand that you are entering another nation. Respect their laws, customs, and leadership.

- Educate Yourself: Research the specific tribe whose lands you are visiting. Learn about their history, government, and cultural protocols. Many tribes have excellent websites.

- Support Tribal Economies: Purchase goods and services directly from tribal businesses, artists, and artisans. This directly benefits the community.

- Seek Permission: For photography, interviews, or participation in ceremonies, always ask permission first.

- Visit Cultural Centers & Museums: These institutions, often tribally run, offer invaluable insights directly from the source.

- Be a Guest, Not a Spectator: Approach your visit with humility and a genuine desire to learn.

The "map" of Native American local government relations is not static; it is a living, evolving tapestry of history, law, identity, and resilience. By moving beyond simplistic notions of "reservations" and embracing the reality of sovereign Native nations, travelers and students of history can unlock a deeper, more meaningful understanding of North America’s past and present, enriching their own journeys and fostering a future built on respect and mutual understanding.