Unveiling the Invisible Map: A Traveler’s Guide to Native American Federal Relations, History, and Identity

For the curious traveler and the earnest student of history, the map of the United States holds more than just state lines and geographical features. Beneath the surface, woven into the very fabric of the land, lies an "invisible map"—a complex, dynamic tapestry of Native American federal relations, sovereignty, and enduring identity. This isn’t just about dots on a map indicating reservations; it’s about understanding the living history, the distinct nations, and the profound resilience that defines Indigenous America. To truly appreciate the landscapes and cultures you encounter, one must first grasp this intricate historical and political framework.

Pre-Colonial Foundations: A Tapestry of Nations, Not Tribes

Before European contact, the continent now known as North America was home to hundreds of distinct, self-governing nations, each with its own language, political system, spiritual beliefs, and intricate cultural practices. From the agricultural societies of the Ancestral Puebloans in the Southwest to the sophisticated confederacies of the Iroquois in the Northeast, and the vast hunting grounds of the Plains Nations, Indigenous peoples lived in complex, thriving societies, managing their lands and resources sustainably for millennia. These were not amorphous "tribes" in a generic sense, but sovereign nations with established diplomatic protocols, trade networks, and distinct identities. Understanding this foundational truth—that Indigenous peoples existed and thrived as nations long before the concept of "federal relations" even emerged—is crucial to appreciating the subsequent history.

The Shifting Sands of Encounter: Early Diplomacy and the Treaty Era

The initial interactions between European powers and Native nations were often conducted on a nation-to-nation basis, recognizing Indigenous sovereignty. Treaties were signed, outlining boundaries, trade agreements, and mutual defense pacts. For Native nations, treaties were sacred, reflecting solemn agreements between equals. For European powers, and later the United States, treaties often became tools of expansion, frequently broken, reinterpreted, or coerced under duress.

The early United States, fresh from its own fight for independence, initially adopted a policy of treating Native nations as foreign entities. Landmark Supreme Court cases, particularly Worcester v. Georgia (1832), affirmed the sovereignty of Cherokee Nation, describing Native nations as "distinct, independent political communities" with whom the federal government had a unique "trust relationship." This "trust responsibility" meant the U.S. government had a legal and moral obligation to protect Native lands, assets, resources, and treaty rights. However, this legal recognition often clashed with the burgeoning expansionist desires of the young republic.

The Era of Removal and Reservation: A Forced Reshaping of the Map

The 19th century witnessed a dramatic shift in U.S. policy, driven by land hunger and Manifest Destiny. The Indian Removal Act of 1830, championed by President Andrew Jackson, authorized the forced displacement of Southeastern Native nations (Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole) to lands west of the Mississippi River. The infamous "Trail of Tears"—the forced march of the Cherokee Nation—epitomizes this brutal chapter, resulting in the deaths of thousands and the loss of ancestral lands.

This era solidified the concept of the "reservation." Initially conceived as isolated areas where Native peoples could be contained and "civilized," reservations became involuntary homelands. They were lands "reserved" by Native nations in treaties, or set aside by executive order, often far removed from their ancestral territories. While intended to isolate and control, reservations ironically became crucibles of cultural preservation and eventually, centers for renewed self-determination. They represent a fundamental paradox: a forced imposition that ultimately served as a bastion of identity.

Allotment and Assimilation: Stripping Identity and Land

The late 19th century brought another devastating policy: allotment. The General Allotment Act (Dawes Act) of 1887 aimed to break up communally held reservation lands into individual parcels, intending to force Native Americans into a Euro-American model of private land ownership and farming. The "surplus" lands, after allotments were made, were then opened up to non-Native settlers. This policy was catastrophic, leading to the loss of two-thirds of the remaining Native land base—from 138 million acres in 1887 to 48 million in 1934.

Beyond land loss, allotment sought to destroy tribal governments and communal identities. Simultaneously, federal boarding schools were established, forcibly removing Native children from their families and cultures, forbidding their languages and traditions, and instilling Christian, American values. The mantra "kill the Indian, save the man" encapsulated this genocidal cultural policy, which inflicted deep, intergenerational trauma still felt today.

Reorganization and Resilience: A Turn Towards Self-Governance

The disastrous consequences of allotment and assimilation became undeniable by the early 20th century. The Meriam Report of 1928 exposed the abject poverty, poor health, and cultural destruction wrought by federal policies. This led to the Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) of 1934, often called the "Indian New Deal." The IRA ended the allotment policy, encouraged tribes to adopt constitutional governments (often modeled on Western structures), and provided some economic development assistance. While still under federal oversight, the IRA marked a significant shift towards recognizing tribal self-governance and halting the erosion of the land base. It was a crucial step in the long journey towards self-determination.

Termination and Its Aftermath: Another Policy U-Turn

Mid-20th century policy took another bewildering turn with "Termination." From the 1940s through the 1960s, the U.S. government pursued policies aimed at ending its trust relationship with Native nations, abolishing reservations, and assimilating Native peoples into mainstream society. The stated goal was to free Native Americans from federal control; the actual effect was devastating. Over 100 tribes were terminated, losing federal recognition, treaty rights, and access to essential services. This led to widespread poverty, cultural disruption, and the loss of remaining lands. The Menominee Nation of Wisconsin, for example, saw its thriving tribal enterprises dismantled and its people plunged into poverty. Termination was eventually repealed due to overwhelming Native advocacy and public outcry, leading to the restoration of federal recognition for many terminated tribes.

The Self-Determination Era: Modern Sovereignty and Empowerment

The late 1960s and early 1970s ushered in the "Self-Determination Era," a profound and lasting paradigm shift. Influenced by the Civil Rights Movement and powerful Native American activism (including events like the occupation of Alcatraz and Wounded Knee), President Richard Nixon formally repudiated termination. The Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act (ISDEAA) of 1975 allowed tribes to contract with the federal government to run their own programs and services, rather than having them dictated by the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA).

This era affirmed the inherent sovereignty of Native nations—their right to govern themselves, manage their own affairs, and exercise jurisdiction over their lands and citizens. It recognized that tribes are not merely interest groups, but distinct governments with a nation-to-nation relationship with the United States. This sovereignty is exercised through tribal courts, law enforcement, healthcare systems, schools, and cultural programs. It also underlies the significant economic development seen on many reservations, particularly through gaming, which is allowed because tribes, as sovereign entities, have the right to regulate activities on their own lands.

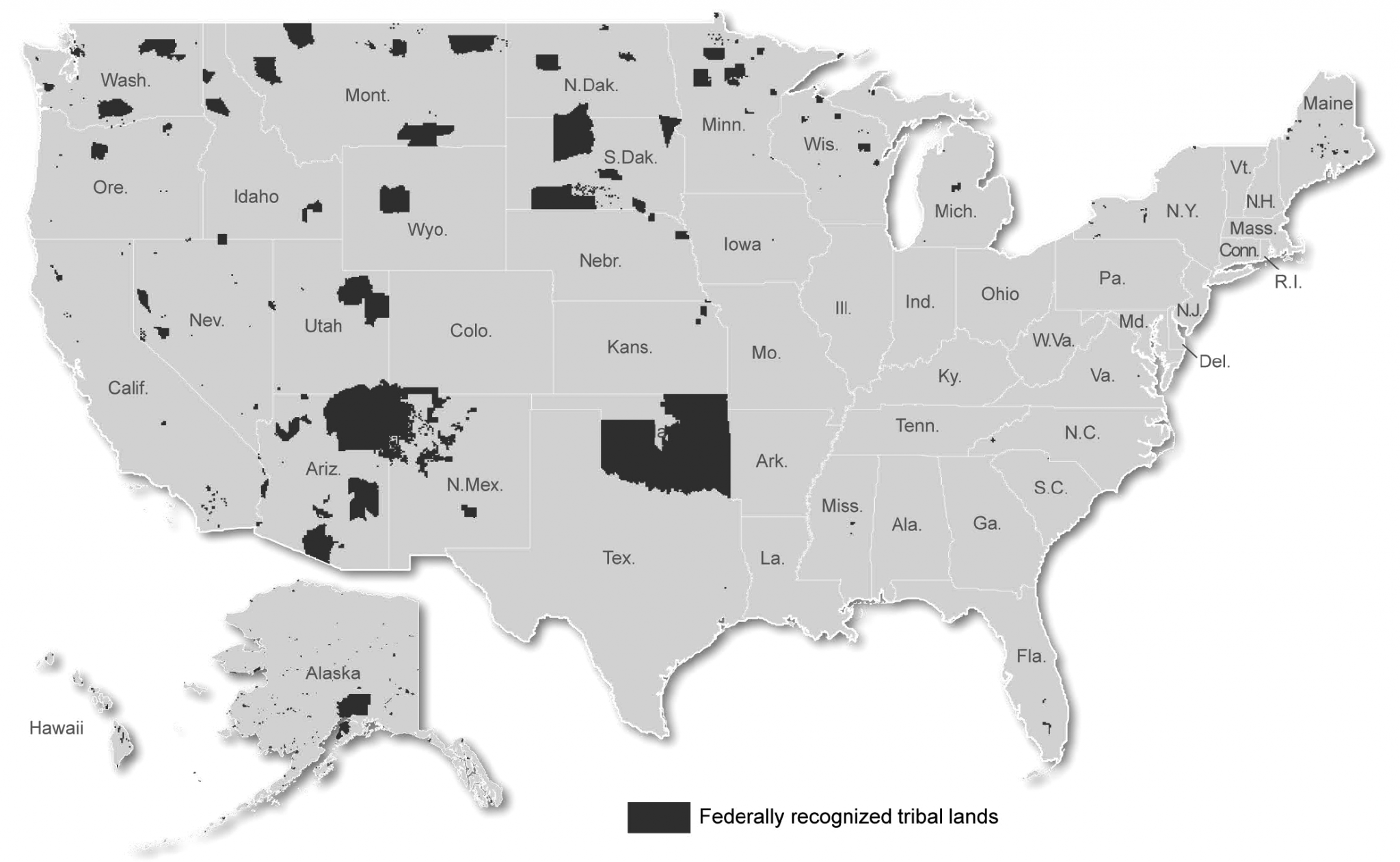

The Contemporary Map: Reservations, Trust Lands, and Unceded Territories

Today, the "map of federal relations" is a vibrant mosaic.

- Reservations: These are not federal property but lands held in trust by the U.S. for the benefit of tribal nations. They are sovereign territories where tribal governments exercise jurisdiction. Visiting a reservation means entering another nation, requiring respect for its laws, customs, and governance.

- Trust Lands: These are lands where the legal title is held by the U.S. government, but the beneficial interest is held by an individual Native American or a tribe. They are often part of or adjacent to reservations.

- Fee Simple Lands: These are lands owned outright by individual Native Americans or tribes, much like any private property.

- Unceded Territories: Many parts of the United States, particularly in the West, are lands never formally ceded by treaty to the U.S. government. Ongoing land claims, treaty rights disputes (e.g., hunting, fishing, water rights), and protests against resource extraction on traditional lands are rooted in these historical facts.

The map is also often "checkerboarded," meaning that within the exterior boundaries of a reservation, there can be a mix of tribal trust lands, individual Native American allotments, and non-Native owned fee simple lands. This complex jurisdictional landscape often leads to challenges in governance and law enforcement, but it also reflects the enduring presence and resilience of Native communities despite centuries of land loss.

Identity and Cultural Resilience in the 21st Century

The historical policies of the U.S. government were largely aimed at eradicating Native American identity. Yet, Native identity persists, thrives, and evolves. It is deeply rooted in:

- Language and Culture: Vigorous efforts are underway to revitalize endangered Indigenous languages and cultural practices, often through immersion schools and community programs.

- Spiritual Connection to Land: For many Native peoples, the land is not merely property but a living relative, imbued with spiritual significance and ancestral memory. This connection informs environmental stewardship and cultural practices.

- Family and Community: Strong kinship ties and community networks remain central to Native identity, providing support and cultural continuity.

- Political Identity: Being a citizen of a sovereign Native nation is a powerful aspect of identity, asserting self-determination and cultural pride.

Modern Native nations face ongoing challenges: economic disparities, inadequate healthcare, environmental threats to traditional lands, and the lingering effects of historical trauma. Yet, they also demonstrate incredible strength, innovation, and adaptability. From developing sustainable economies and renewable energy projects to advocating for climate justice and cultural heritage protection, Native nations are powerful forces in the 21st century.

Traveling and Engaging with Native Nations: A Call to Respect and Education

For the traveler, understanding this "invisible map" transforms a scenic drive into a journey through living history. When you visit places like the Navajo Nation, the Oglala Lakota’s Pine Ridge Reservation, or the pueblos of New Mexico, you are not just seeing landscapes; you are witnessing the enduring legacy of sovereign nations.

To be a respectful and informed traveler:

- Recognize Sovereignty: Understand that you are entering another nation. Respect tribal laws, customs, and authorities.

- Support Tribal Economies: Purchase goods and services directly from Native artists, businesses, and cultural centers. This directly benefits the community.

- Learn Before You Go: Research the history and contemporary issues of the specific Native nation whose lands you plan to visit. Many tribes have excellent websites.

- Visit Cultural Centers and Museums: These are invaluable resources for learning directly from Native perspectives.

- Ask Permission: Before taking photos of people or participating in ceremonies, always ask for permission. Some sites or events may be sacred and not open to the public or photography.

- Be Mindful of Language: Use respectful terminology. "Native American," "Indigenous peoples," and referring to specific tribal names are generally preferred over outdated or generic terms.

Conclusion

The map of Native American federal relations is not static; it is a dynamic, evolving story of struggle, resilience, and sovereignty. It is a story etched into the land, carried in the languages, and expressed in the vibrant cultures of hundreds of distinct nations. For the traveler and the student alike, truly understanding this invisible map enriches the experience of America, revealing its complex past and its enduring, diverse present. It’s a call to look beyond superficial boundaries and recognize the living nations, their histories, their identities, and their rightful place in the ongoing narrative of this continent. By doing so, we not only become better travelers but more informed and respectful citizens of the world.