>

Navigating the Invisible Map: Understanding Native American Intergovernmental Relations

When we speak of a "map" in the context of Native American intergovernmental relations, we are not primarily referring to lines on a physical atlas. Instead, we are exploring a complex, living tapestry woven from history, law, culture, and identity—a dynamic web of relationships that defines the very essence of Indigenous nationhood within the United States. For travelers and history enthusiasts seeking a deeper understanding of America’s true heritage, comprehending this "invisible map" is crucial to respectfully engaging with Native cultures and appreciating their enduring sovereignty.

This map charts the intricate interactions between federally recognized Native American tribes and nations, the U.S. federal government, state governments, and even other tribal governments. It’s a story of profound resilience, persistent struggle, and unwavering self-determination, offering a lens through which to view the diverse and vibrant Indigenous societies that predate and continue to shape this continent.

The Deep Roots: Pre-Contact Sovereignty and Early Encounters

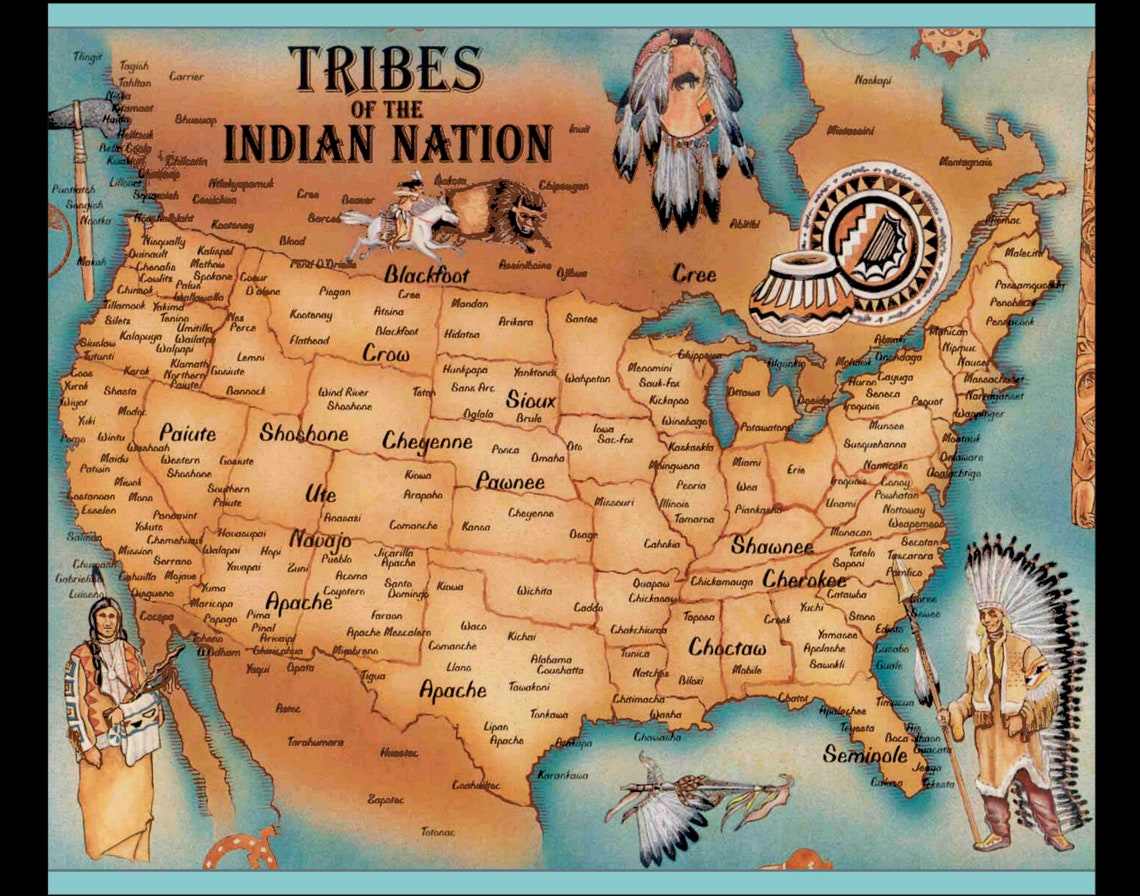

To truly understand this map, we must first acknowledge the starting point: a continent inhabited by hundreds of distinct Indigenous nations, each with its own language, governance structures, economic systems, spiritual beliefs, and territories. These were not mere "bands" but complex societies—nations that engaged in diplomacy, trade, and warfare with their neighbors, exercising full inherent sovereignty long before European arrival.

The initial encounters between European powers (Spain, France, England) and Native nations were often conducted on a nation-to-nation basis. Early treaties, though frequently broken or misunderstood, formally recognized Native tribes as sovereign entities capable of negotiating land cessions, alliances, and peace agreements. This foundational principle—that Native nations possessed inherent sovereignty—was later adopted, albeit imperfectly, by the nascent United States.

The Shifting Sands: The Formative Years of U.S.-Tribal Relations

The U.S. Constitution itself acknowledges Native nations, placing "commerce with the Indian Tribes" under federal purview, distinct from foreign nations and individual states. This set the stage for a unique legal and political relationship, often termed the "trust relationship," where the federal government assumed a guardian-like role, theoretically protecting tribal lands and resources.

However, the 19th century saw this relationship devolve into a period of aggressive expansionism and dispossession. Landmark Supreme Court cases like Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (1831) and Worcester v. Georgia (1832), articulated by Chief Justice John Marshall, defined tribes as "domestic dependent nations." While acknowledging their distinct political status and inherent sovereignty, this ruling also placed them under the "protection" of the U.S. government, denying them the status of foreign nations in a legal sense. This legal paradox—sovereign yet dependent—would define the relationship for centuries.

The Indian Removal Act of 1830 epitomized the federal government’s policy of forced displacement, culminating in the tragic Trail of Tears. Tribes were forcibly relocated to lands west of the Mississippi, often under brutal conditions, paving the way for further U.S. settlement. The creation of reservations—areas of land set aside for tribal use—initially served as a tool of containment, yet paradoxically, they also became bastions of cultural survival and the physical embodiments of tribal nationhood.

The Eras of Assimilation and Termination: Attacks on Identity and Nationhood

The late 19th and early 20th centuries witnessed a relentless assault on Native identity and self-governance. The Dawes Allotment Act of 1887 sought to dismantle communal land ownership, dividing reservations into individual parcels and selling off "surplus" lands to non-Native settlers. This policy aimed to break down tribal structures, assimilate Native people into mainstream American society, and further erode their land base. Its devastating impact led to the loss of millions of acres of tribal land and severely undermined traditional governance.

Parallel to this, federal Indian boarding schools aggressively pursued a policy of cultural genocide, separating Native children from their families, languages, and traditions. The goal was explicit: "Kill the Indian, save the man." These policies aimed to erase the distinct identities that underpinned Native nationhood, thereby simplifying the intergovernmental "map" by attempting to remove one of its primary players.

The mid-20th century brought another seismic shift with the Termination Era (1950s-1960s). Driven by a desire to "free" Native Americans from federal supervision and assimilate them fully, Congress passed legislation that unilaterally terminated the federal recognition of over 100 tribes, dissolving their reservations, and ending their special relationship with the U.S. government. This disastrous policy resulted in profound economic hardship, loss of land, and cultural dislocation for the affected tribes, demonstrating the immense power the federal government wielded over tribal existence.

The Dawn of Self-Determination: Rebuilding the Map

The tide began to turn in the 1960s and 70s, fueled by the Civil Rights Movement and growing Indigenous activism. The Nixon administration, in a pivotal shift, declared an end to termination and ushered in the era of "self-determination." This new policy recognized the right of Native nations to govern themselves and control their own affairs.

The Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act (ISDEAA) of 1975 was a cornerstone of this era. It allowed tribes to contract with the federal government to operate their own programs and services—such as healthcare, education, and law enforcement—that were previously administered by federal agencies like the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) or the Indian Health Service (IHS). This marked a significant step towards restoring tribal sovereignty and rebuilding governmental capacity.

Today, there are 574 federally recognized Native American tribes and nations in the United States, each with a government-to-government relationship with the U.S. federal government. This recognition grants them specific rights, powers, and responsibilities, including the ability to:

- Formulate their own laws and judicial systems: Many tribes have their own police forces, courts, and detention facilities.

- Manage their lands and natural resources: This includes environmental protection, water rights, and resource development.

- Determine their own membership: Tribes define who is a citizen of their nation.

- Tax and regulate commerce within their territories: This is a key aspect of economic development and self-sufficiency.

- Provide essential services: Healthcare, education, housing, and infrastructure.

The Modern Map: A Multifaceted Web of Relations

The contemporary "map" of Native American intergovernmental relations is a complex, multi-layered construct:

- Federal-Tribal Relations: This remains the primary relationship. It’s rooted in treaties, federal statutes, executive orders, and court decisions. It’s a "government-to-government" relationship, acknowledging tribal nations as distinct sovereign entities. The federal "trust responsibility" continues to be a crucial, though often contentious, aspect, obligating the U.S. to protect tribal assets, resources, and treaty rights.

- State-Tribal Relations: While the U.S. Constitution generally restricts states from interfering with tribal affairs, the reality is far more nuanced. Many states have significant Native populations and tribal lands within their borders, leading to complex jurisdictional issues over taxation, law enforcement, environmental regulation, and gaming compacts. Some states have developed robust government-to-government relationships with tribes, while others remain resistant to recognizing tribal authority.

- Inter-Tribal Relations: This vital layer often goes unnoticed but is critical to Native identity and resilience. Tribes engage in extensive diplomacy, collaboration, and resource sharing with one another. Regional and national inter-tribal organizations (like the National Congress of American Indians or the Great Plains Tribal Chairman’s Association) advocate for collective interests, share best practices, and strengthen the collective voice of Indigenous nations.

- International Engagement: Some Native nations, particularly those with historical treaties predating the U.S., also engage with international bodies and foreign governments, asserting their inherent sovereignty on a global stage.

Identity and the Enduring Power of Nationhood

At the heart of this intergovernmental map lies identity. For Native peoples, identity is inextricably linked to their nation, their land, their language, and their cultural practices. The long struggle for self-determination has been a fight not just for political rights, but for the right to maintain and celebrate these unique identities.

Travelers visiting tribal lands will encounter this vibrant reality. You might see tribal flags flying alongside state and national flags, visit tribal museums showcasing millennia of history, learn about language revitalization efforts, or witness contemporary art that blends tradition with modern expression. Economic ventures, from casinos and resorts to energy projects and agricultural enterprises, are not merely businesses; they are expressions of sovereignty, designed to create jobs, fund essential services, and strengthen tribal self-sufficiency.

Navigating the Map: A Call for Respectful Engagement

For those seeking to explore this "invisible map," respectful engagement is paramount:

- Recognize Sovereignty: Understand that when you visit a reservation, you are entering another nation. Respect their laws, customs, and authorities.

- Educate Yourself: Learn about the specific history, culture, and governance of the tribe whose lands you are visiting. Many tribes have excellent cultural centers and museums.

- Support Tribal Enterprises: Patronize tribally owned businesses, artists, and tour operators. Your dollars directly support tribal economies and services.

- Listen to Indigenous Voices: Seek out opportunities to learn directly from tribal members, elders, and cultural practitioners.

The map of Native American intergovernmental relations is not static; it is constantly evolving, shaped by ongoing legal battles, political negotiations, and the unwavering determination of Native nations to protect their sovereignty and cultural heritage. By understanding this complex landscape, we gain a deeper appreciation for the enduring strength, diversity, and vital contributions of Indigenous peoples to the fabric of North America—a journey well worth taking for any curious traveler or student of history.