>

Mapping Sovereignty: The Unseen Battle for Native American Voting Rights

Imagine a map. Not just lines on a page, but a living, breathing document of history, struggle, and enduring identity. When we talk about a "Map of Native American voting rights," we’re not referring to a single, static cartographic image. Instead, we’re envisioning an intricate overlay of ancestral tribal lands, federal and state jurisdictions, and the complex web of laws, cultural practices, and socio-economic realities that have shaped, and continue to shape, the ability of Indigenous peoples to cast their ballot. For the traveler and history enthusiast, understanding this "map" is essential to truly grasping the landscape of American democracy and the profound resilience of its First Peoples.

This isn’t merely a political issue; it’s a story deeply rooted in sovereignty, self-determination, and the very definition of citizenship. It’s a journey that takes us from the earliest days of European contact to the modern polling place, revealing layers of disenfranchisement, hard-won victories, and ongoing challenges.

The Invisible Lines: Beyond Geographic Borders

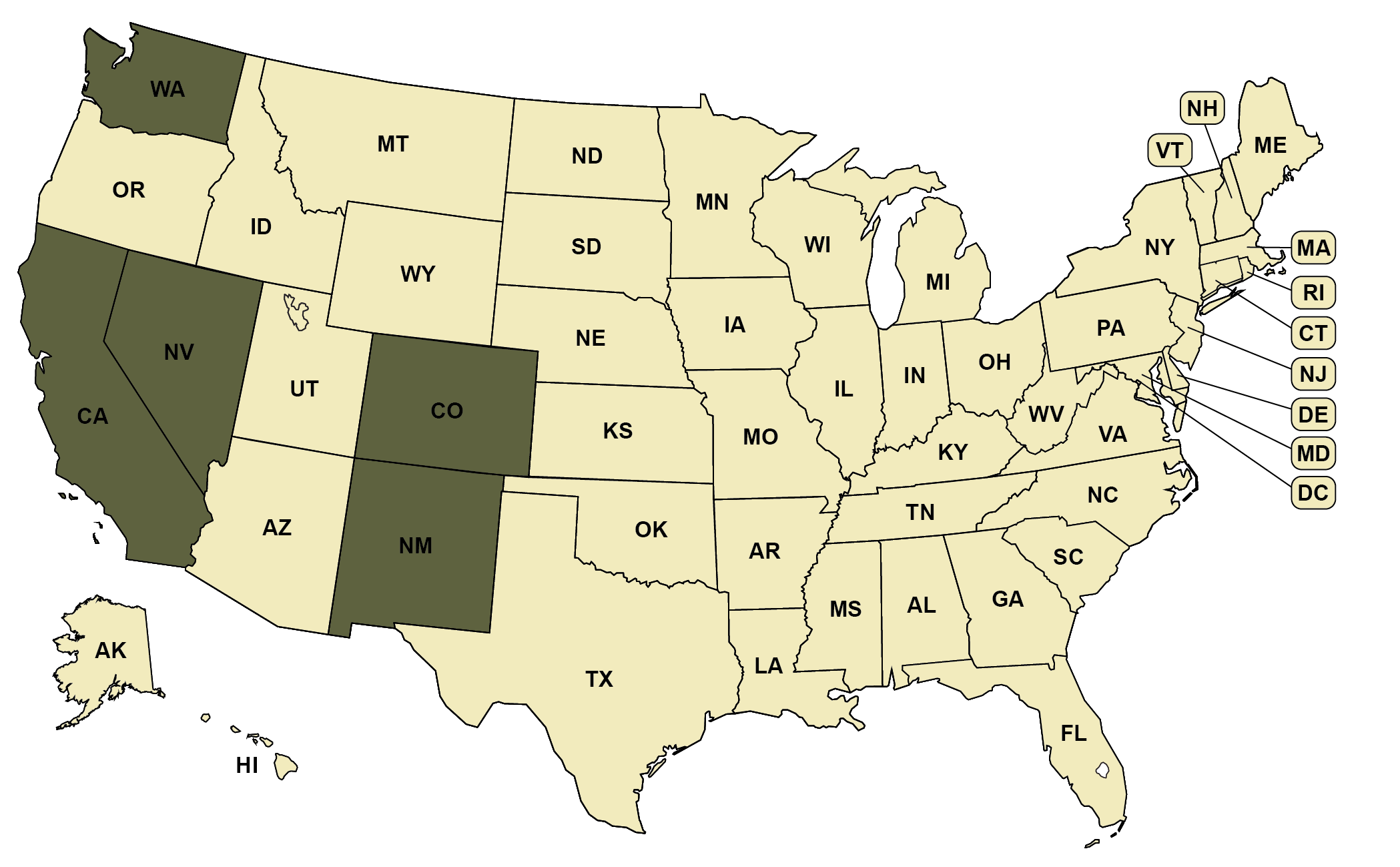

To understand this conceptual map, we must first acknowledge the physical map of Native American tribes. Over 574 federally recognized tribes, and many more state-recognized or unrecognized, occupy distinct territories—often referred to as reservations—across the United States. These lands are not simply parcels of property; they are homelands, sacred spaces, and the physical manifestations of tribal sovereignty. Each tribe possesses a unique history, language, and cultural identity.

The "Map of Native American voting rights" is superimposed upon this tribal landscape, illustrating where the right to vote has been granted, denied, obstructed, or championed. It shows the concentrations of Native populations, the distances to polling places, the linguistic diversity requiring translated materials, and the socio-economic factors that often create barriers. It’s a map not of what is, but of what has been and what could be.

A Century of Struggle: Historical Roots of Disenfranchisement

The history of Native American voting rights is a stark reminder that citizenship and suffrage have been anything but universal in the United States. For centuries, Indigenous peoples were considered "domestic dependent nations" or foreign subjects, not citizens of the U.S. and therefore ineligible to vote.

-

Early Eras (Pre-1924): Before the 20th century, Native Americans were largely excluded from the body politic. The prevailing view was that they were members of separate, sovereign nations. While some treaties contained provisions that could have been interpreted as granting certain rights, the general consensus was one of exclusion. The Dawes Act of 1887, which aimed to assimilate Native Americans by breaking up communal tribal lands into individual allotments, did offer citizenship to those who accepted allotments and severed ties with their tribes. However, this was often a coercive measure designed to dismantle tribal structures, and it still didn’t guarantee voting rights in practice.

-

The Indian Citizenship Act of 1924: This was a monumental piece of legislation, granting U.S. citizenship to all Native Americans born within the territorial limits of the United States. It was a victory, but it was far from a complete solution. Crucially, the Act did not automatically guarantee voting rights. States retained the power to regulate suffrage, and many states—especially in the West—continued to erect formidable barriers.

-

State-Level Resistance (Post-1924 to 1960s): Even after 1924, states like Arizona, New Mexico, Maine, and Utah actively denied Native Americans the right to vote for decades. Common tactics included:

- "Ward of the State" Status: Arguing that Native Americans living on reservations were under federal guardianship and thus not residents of the state for voting purposes. Arizona and New Mexico upheld this until 1948 and 1962, respectively.

- Literacy Tests: Discriminatory tests designed to disenfranchise those who didn’t speak English or had limited access to formal education.

- Poll Taxes: Financial burdens that disproportionately affected impoverished communities.

- Residency Requirements: Complex rules that made it difficult for those living on reservations to prove state residency.

- Intimidation and Violence: Overt and covert threats to prevent Native Americans from registering or voting.

It wasn’t until the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and subsequent amendments, that many of these explicit state-level barriers were finally dismantled. Even then, the unique challenges faced by Native communities required further specific protections, eventually leading to the 1975 amendments that included provisions for language assistance.

Identity and Sovereignty: The Cultural Dimension of the Vote

For Native Americans, voting is not just an individual civic duty; it’s often an act deeply intertwined with tribal identity, sovereignty, and the future of their communities. Many Native people hold a dual citizenship—both as citizens of their tribal nation and as citizens of the United States. This dual identity informs their political engagement.

Voting becomes a crucial mechanism for:

- Protecting Treaty Rights: Many tribes have treaties with the U.S. government that guarantee specific rights to land, resources, and self-governance. Voting for candidates who respect and uphold these treaties is paramount.

- Preserving Culture and Language: Political representation can ensure funding for cultural programs, language revitalization efforts, and educational initiatives that safeguard unique Indigenous identities.

- Exercising Self-Determination: The ability to influence local, state, and federal policy directly impacts the autonomy and well-being of tribal nations, from healthcare and education to environmental protection and economic development on reservations.

- Honoring Ancestors: For many, the fight for the vote is a continuation of their ancestors’ struggles for survival and justice, a way to ensure their voices are heard in a system that historically sought to silence them.

When a Native American casts a ballot, they are often voting not just for themselves, but for their family, their tribe, their land, and their heritage. It’s a collective act of sovereignty, asserting their right to exist and thrive on their ancestral homelands.

Modern Obstacles: The Map of Ongoing Challenges

Despite historical victories, the "map" of Native American voting rights today still reveals significant obstacles, many of which are unique to Indigenous communities:

-

Geographic Isolation and Lack of Infrastructure: Many reservations are remote, covering vast areas with sparse populations. This translates to:

- Few Polling Places: Voters may have to travel dozens or even hundreds of miles to reach a polling site.

- Lack of Transportation: Limited access to reliable vehicles or public transportation on reservations.

- Limited Mail Services: Inconsistent or slow mail delivery can hinder absentee ballot applications and returns.

- Lack of Internet/Phone Access: Essential for online voter registration, accessing election information, and staying informed.

-

Voter ID Laws and Address Issues: Stringent voter ID laws disproportionately affect Native communities. Many residents on reservations lack standard street addresses, instead using P.O. boxes or descriptive directions. This can complicate voter registration forms and make it difficult to obtain state-issued IDs that require a physical address. While tribal IDs are valid forms of identification, they are not universally accepted at polling places across all states, creating an unnecessary hurdle.

-

Language Barriers: Despite the 1975 VRA amendments, access to translated election materials and bilingual poll workers remains a challenge in many areas, particularly for elders or those who primarily speak their tribal language.

-

Gerrymandering and Voter Roll Purges: Native communities, like other minority groups, are often targeted by partisan gerrymandering that dilutes their voting power. Aggressive voter roll purges can also disproportionately remove eligible Native voters due to address inconsistencies or inactive voter status, especially if they have limited access to mail or internet to confirm their registration.

-

Historical Trauma and Distrust: Generations of broken promises, cultural suppression, and political marginalization have fostered a deep-seated distrust in government systems. Overcoming this historical trauma and encouraging participation requires consistent, culturally sensitive outreach.

These obstacles are not accidental; they are systemic challenges that create a "voter suppression map" that largely overlays the "tribal lands map," highlighting areas where Indigenous voices are still being marginalized.

The Power of the Native Vote: Shaping the Future

Despite these challenges, the Native American vote is a powerful and growing force. In recent elections, particularly in swing states with significant Indigenous populations like Arizona, New Mexico, Nevada, and North Dakota, the Native vote has proven decisive.

- Increased Mobilization: Tribal nations and Native-led organizations are increasingly investing in voter registration, education, and get-out-the-vote efforts, often employing innovative, culturally relevant strategies.

- Political Representation: More Native Americans are running for office and winning, bringing essential Indigenous perspectives to state legislatures, Congress, and local governments.

- Impact on Key Issues: The Native vote is critical for advancing issues such as environmental protection, water rights, healthcare access, sacred site protection, and addressing the crisis of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls (MMIWG).

- Youth Engagement: A growing movement of young Indigenous activists and leaders are leveraging social media and community organizing to empower their peers and demand a voice in the political process.

The map of Native American voting rights is therefore not just a map of problems, but also a map of burgeoning political power, demonstrating the resilience and determination of Indigenous communities to assert their rightful place in American democracy.

For the Traveler and Learner: Engaging with This Map

For those traveling through Native lands or interested in history and education, understanding this complex "map" offers a profound opportunity for deeper engagement:

- Visit Tribal Cultural Centers and Museums: These institutions offer invaluable insights into specific tribal histories, languages, and contemporary issues. They are windows into the living cultures that shape the political landscape.

- Support Native Businesses: Economic empowerment is intrinsically linked to political power. Supporting Indigenous-owned businesses helps build stronger, more self-sufficient communities.

- Learn Local Tribal History: Before visiting an area, research the Indigenous peoples who traditionally inhabit that land. Understand their treaties, their struggles, and their triumphs. Consider making a land acknowledgment.

- Listen to Native Voices: Seek out and listen to the perspectives of Indigenous leaders, elders, and community members. Attend public forums or events where Native issues are discussed.

- Advocate for Voting Access: Support organizations working to remove barriers to voting for Native Americans. Understanding the challenges is the first step toward advocating for solutions.

The "Map of Native American voting rights" is a testament to an ongoing journey—a journey of asserting sovereignty, preserving identity, and fighting for a voice in a nation that was built on their ancestral lands. It’s a journey that continues today, reminding us that democracy is a dynamic process, constantly shaped by the persistent efforts of those who demand to be heard. As you explore the diverse landscapes of America, remember that beneath the surface, there’s a deeper map of human rights and cultural resilience waiting to be understood and honored.

>