Mapping Resilience: How Native American Traditional Knowledge Protects History and Identity

Beyond the static lines of colonial cartography lie maps that breathe life, knowledge, and sovereignty: maps of Native American traditional knowledge protection. These are not merely geographical representations but intricate tapestries woven from centuries of ancestral wisdom, cultural identity, and an unwavering commitment to stewardship. Far from being quaint relics of the past, these maps are dynamic, living documents, crucial tools in the ongoing struggle for self-determination, environmental justice, and the revitalization of Indigenous cultures in North America. For the traveler and the student of history alike, understanding these maps offers a profound gateway into the enduring legacy and contemporary resilience of Native American nations.

The Deep Roots of Indigenous Cartography

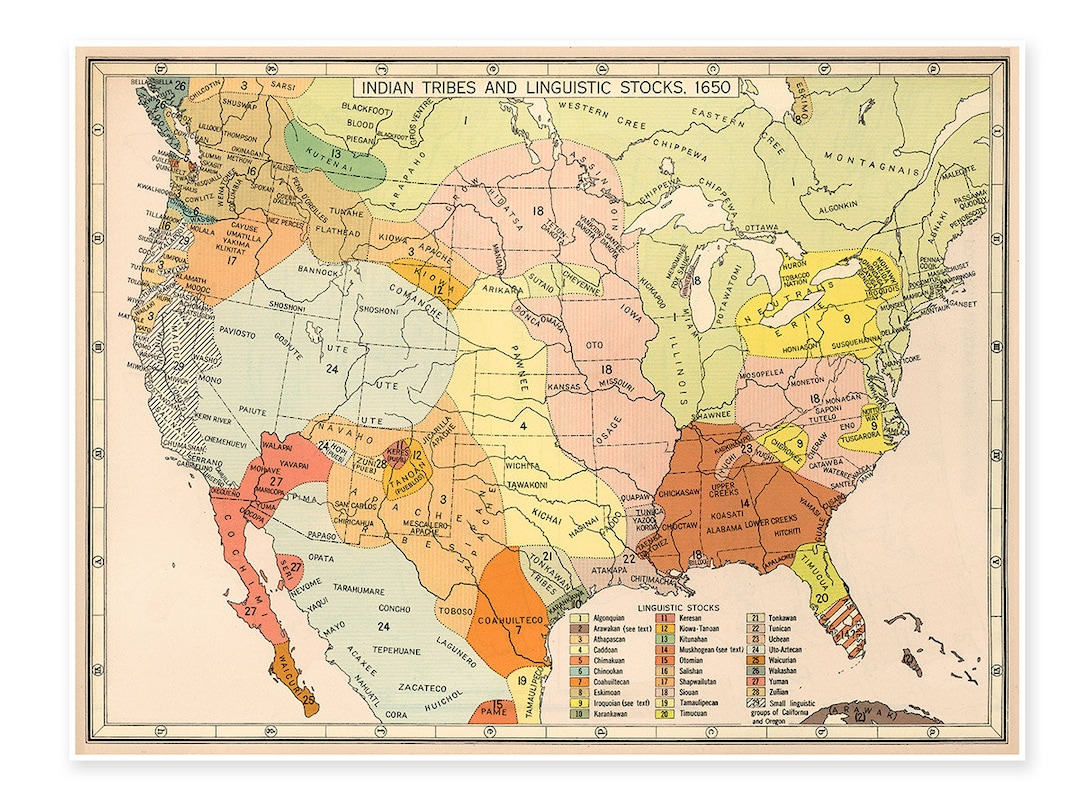

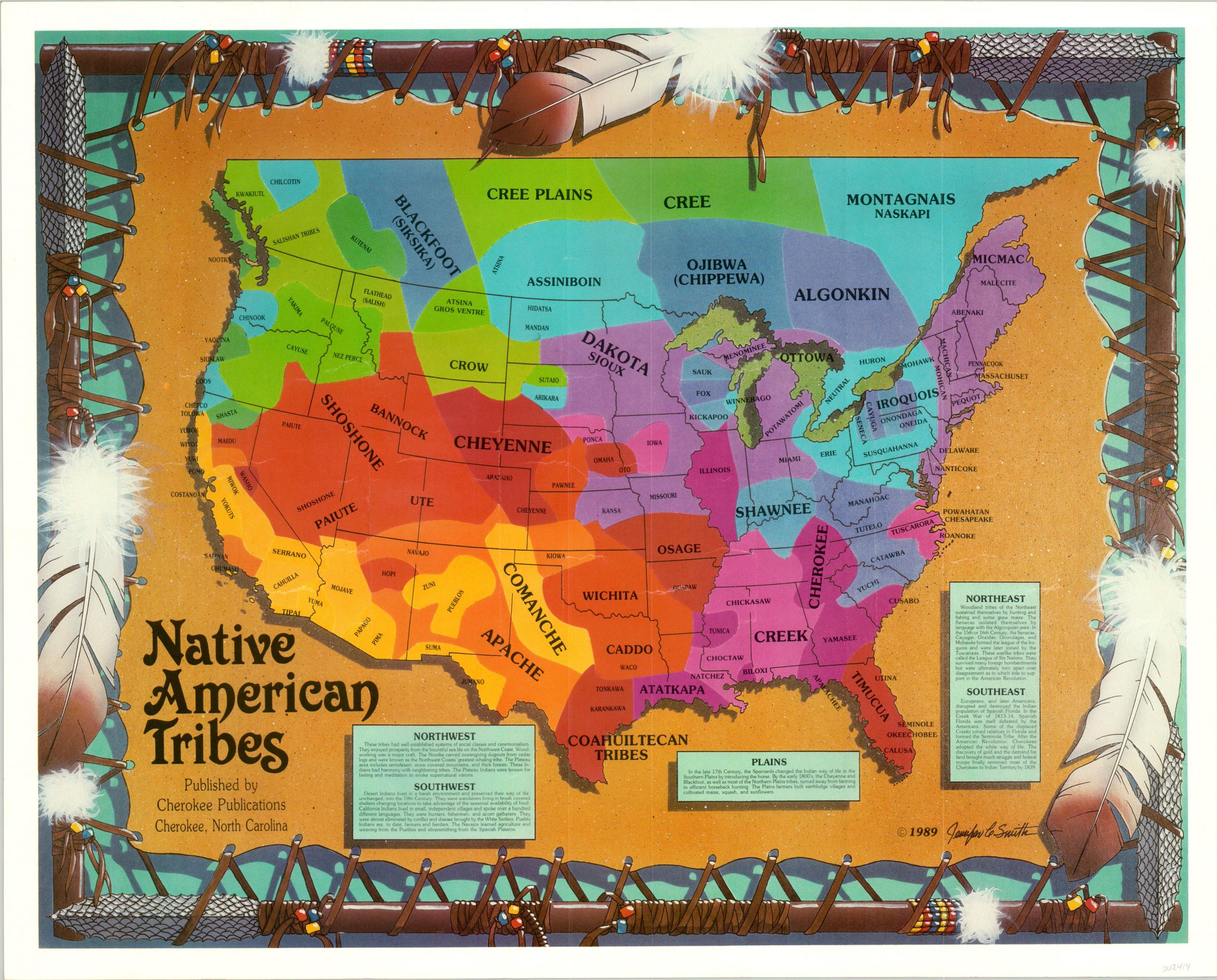

To understand traditional knowledge protection maps, one must first decolonize the very concept of "map." Before European contact, Indigenous peoples across North America possessed sophisticated systems of spatial understanding and knowledge transmission. These "maps" were embedded in oral histories, ceremonial routes, seasonal migration patterns, star charts, pictographs, petroglyphs, and even intricate fiber arts or wampum belts. They encoded vital information about sacred sites, resource availability, ecological processes, kinship networks, and historical events. This knowledge was not abstract; it was inextricably linked to identity, spirituality, and survival, passed down through generations.

The arrival of European colonizers introduced a new, alien form of cartography: one of conquest, division, and ownership. Colonial maps flattened complex cultural landscapes into grids for resource extraction, land speculation, and the forceful removal of Indigenous peoples. Rivers became boundaries, mountains became resources, and ancestral territories were erased or renamed. This imposition of foreign geographical frameworks was a deliberate act of dispossession, severing Indigenous peoples from the lands that defined their existence and sustained their knowledge systems.

What are Traditional Knowledge Protection Maps Today?

In response to this historical trauma and ongoing threats, Native American traditional knowledge protection maps have emerged as powerful tools for reclamation and assertion. These contemporary maps are multifaceted, serving several critical functions:

- Documentation and Preservation: They meticulously record traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) – information about plant uses, animal behaviors, water sources, climate patterns, and sustainable land management practices. This includes documenting sacred sites, burial grounds, ceremonial places, and historical village locations that are often invisible or dismissed by mainstream maps.

- Legal and Political Advocacy: These maps provide irrefutable evidence for land claims, treaty rights, and environmental protection. They are used in legal battles against resource extraction projects (mining, logging, oil pipelines) that threaten ancestral lands, demonstrating the profound cultural and ecological impact of such developments. They assert Indigenous jurisdiction over territories often depicted as "public lands" or "unoccupied."

- Cultural Revitalization and Education: By making traditional knowledge visible and accessible (within culturally appropriate boundaries), these maps help revitalize languages, ceremonies, and traditional practices. They are invaluable educational tools for younger generations, reconnecting them to their heritage and fostering a sense of pride and stewardship.

- Community Empowerment and Self-Determination: The process of creating these maps is often community-led, involving elders, knowledge keepers, youth, and mapping specialists. This collaborative effort strengthens community bonds, reinforces collective memory, and empowers tribes to assert control over their own narratives and resources.

Unlike colonial maps, which often sought to simplify and control, Indigenous protection maps embrace complexity. They integrate qualitative data—stories, songs, personal testimonies—with quantitative geographical information. They are often dynamic, designed to be updated as knowledge evolves or as new threats emerge.

Identity: Land as the Foundation of Being

For Native American peoples, identity is fundamentally rooted in a spiritual, historical, and practical relationship with the land. This is not mere sentimentality; it is an epistemology, a way of knowing and being in the world. The land is seen as a relative, a provider, a library of ancestral wisdom, and the source of cultural practices, languages, and ceremonies.

Traditional knowledge protection maps embody this profound connection. When a map identifies a sacred spring, it’s not just a water source; it’s a place where ceremonies are performed, where ancestors are remembered, and where specific plant medicines grow. When it delineates a hunting ground, it’s not merely a resource zone; it’s a place where intergenerational knowledge about animal behavior, ethical harvesting, and respect for life is passed down. The very act of mapping these elements reaffirms identity, asserting that "we are still here, and this is who we are, tied to this place."

The forced removal of tribes from their ancestral lands—epitomized by the Trail of Tears and countless other displacements—was a deliberate attempt to sever this connection, to erase identity. Traditional knowledge protection maps directly counter this historical violence by asserting the continuity of Indigenous presence and the enduring validity of their relationship with the land, regardless of imposed borders or legal definitions. They are declarations of nationhood, reminding the world that Native American tribes are sovereign nations with inherent rights to self-governance and cultural preservation.

Historical Context: A Legacy of Resistance and Resilience

The development of traditional knowledge protection maps is deeply intertwined with the history of Native American resistance against colonialism. From the earliest encounters, Indigenous peoples have fought to retain their lands, cultures, and ways of life. Treaties, often broken by the U.S. government, implicitly or explicitly recognized Indigenous territories, but these recognitions were consistently undermined.

The late 20th and 21st centuries have seen a resurgence in Indigenous mapping initiatives, spurred by several factors:

- Growing Recognition of Indigenous Rights: International frameworks like the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) provide a legal and moral basis for asserting rights to lands, territories, and resources, and the protection of traditional knowledge.

- Technological Advancements: Geographic Information Systems (GIS), satellite imagery, and drone technology have become powerful tools, enabling tribes to create highly detailed and sophisticated maps. Crucially, these technologies are increasingly controlled and utilized by Indigenous communities, rather than imposed upon them.

- Environmental Threats: The escalating climate crisis and industrial development pressures have intensified the need for Indigenous-led conservation and management strategies, often informed by TEK and articulated through these maps.

- Cultural Revitalization Movements: A strong emphasis on language preservation, ceremonial revival, and intergenerational knowledge transfer has underscored the importance of documenting and protecting the spatial dimensions of these practices.

Consider the example of the Bears Ears National Monument in Utah. For a coalition of five Southwestern tribes, this area is not just a scenic landscape but a sacred space teeming with ancestral sites, medicinal plants, and cultural significance. Their "Indigenous Land Management Plan" and accompanying maps provide a detailed counter-narrative to government designations, articulating their historical and ongoing stewardship and proposing a co-management framework based on traditional knowledge. These maps illustrate where specific plants are gathered, where ceremonies are performed, and where ancient dwellings stand, demonstrating a profound, intricate relationship with the land that goes far beyond recreational use.

Methodologies: Community-Led and Culturally Appropriate

The creation of traditional knowledge protection maps is rarely a top-down academic exercise. Instead, it is typically a community-driven process, ensuring cultural appropriateness and Indigenous ownership of the data. Key methodologies include:

- Participatory GIS (PGIS): This involves community members directly contributing their knowledge to digital mapping platforms. Elders share stories, youth input data, and all participants collectively decide what information is mapped, how it’s represented, and who has access to it.

- Oral History Interviews: Documenting narratives, place names in Indigenous languages, and personal experiences related to specific geographical features provides rich, qualitative data that adds depth and meaning to the maps.

- Ethnobotanical and Ethnozoological Surveys: Identifying and mapping the locations of culturally significant plants and animals, along with the knowledge associated with their use and conservation.

- Ceremonial and Migration Route Mapping: Tracing traditional paths, seasonal camps, and ceremonial sites, often extending across vast landscapes, to illustrate historical land use and spiritual connections.

- Digital Storytelling and Multimedia Integration: Modern maps can incorporate audio recordings of elders, videos of ceremonies, and historical photographs, transforming static maps into dynamic, immersive cultural archives.

A crucial ethical consideration in this process is data sovereignty. Tribes assert their right to own, control, access, and possess their own data. This means deciding what information is public, what is restricted, and who can use it, preventing the misappropriation or exploitation of sensitive traditional knowledge.

Impact and Future Directions

The impact of traditional knowledge protection maps is far-reaching. They have influenced legal decisions, informed environmental policy, guided archaeological investigations, and played a vital role in the repatriation of ancestral remains and cultural items. They have fostered intertribal collaboration, strengthened cultural pride, and served as powerful tools for intergenerational knowledge transfer.

For travelers and history enthusiasts, these maps offer a profound educational opportunity. They challenge conventional understandings of history, geography, and land ownership, revealing the enduring presence and wisdom of Native American nations. Visiting areas where such mapping has occurred (with respect for local protocols and privacy) allows one to see the landscape through Indigenous eyes, understanding the layers of meaning and history embedded in every feature.

Looking forward, the field of Indigenous cartography is only growing. As technology advances and Indigenous rights gain further recognition, these maps will continue to evolve. They will likely become even more sophisticated, integrating virtual reality, augmented reality, and other immersive technologies to tell stories and transmit knowledge in innovative ways. They will continue to be critical in the fight against climate change, offering Indigenous-led solutions rooted in millennia of ecological understanding.

Conclusion

Traditional knowledge protection maps are far more than just lines on paper or pixels on a screen. They are potent symbols of Native American resilience, declarations of sovereignty, and vital tools for cultural survival. They weave together history, identity, and the profound connection to the land, offering a powerful counter-narrative to centuries of colonial erasure. For anyone seeking a deeper, more truthful understanding of North America’s past and present, these maps provide an essential guide, revealing the living heart of Indigenous nations and their enduring commitment to protecting their heritage for generations to come. They remind us that true knowledge of a place comes not just from its physical features, but from the stories, wisdom, and identities of the peoples who have called it home since time immemorial.