The map of Native American land claims court cases is not merely a static cartographic representation; it is a living, breathing testament to centuries of legal battles, cultural survival, and the enduring fight for sovereignty and identity. For anyone traversing the diverse landscapes of North America, understanding this intricate legal geography is crucial for appreciating the rich history, complex present, and determined future of Indigenous peoples. This map, far from being a simple outline of reservations, reveals the layered history of treaties made and broken, the relentless erosion of Indigenous lands, and the powerful resurgence of Native nations asserting their rights through the American legal system.

The Historical Genesis of Claims: From Contact to Dispossession

The genesis of these land claims lies in the very moment of European contact. Prior to colonization, Indigenous nations held aboriginal title to their ancestral lands, a concept rooted in long-standing occupation and use. European powers, however, asserted their own doctrines—primarily the "doctrine of discovery"—which claimed that European nations gained title to lands they "discovered," diminishing Indigenous land rights to mere occupancy. This foundational legal fiction laid the groundwork for centuries of dispossession.

The nascent United States, after its independence, largely adopted this framework. While acknowledging some form of Indigenous land rights, it asserted the exclusive right to extinguish those rights, primarily through treaties. The treaty era, particularly from the late 18th to mid-19th centuries, saw hundreds of agreements between the U.S. government and various Native nations. These treaties often involved the cession of vast territories in exchange for promises of protected reservations, annuities, and guaranteed rights to hunt, fish, and gather on ceded lands. Crucially, these treaties were considered nation-to-nation agreements, implicitly recognizing the inherent sovereignty of Native tribes.

However, these promises were systematically broken. The relentless westward expansion of American settlers, driven by manifest destiny and the desire for land and resources, led to escalating pressures on tribal territories. The Indian Removal Act of 1830, for example, forcibly relocated numerous Southeastern tribes, including the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole, from their ancestral lands to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma) along the tragic "Trail of Tears," despite earlier treaties guaranteeing their rights. This period marked a profound betrayal and set the stage for future legal battles.

Early Legal Precedents and the Marshall Trilogy

The Supreme Court, under Chief Justice John Marshall, attempted to define the relationship between Native nations and the U.S. government in a series of landmark cases in the 1820s and 1830s, collectively known as the "Marshall Trilogy."

- Johnson v. M’Intosh (1823): This case affirmed the doctrine of discovery, stating that Indigenous nations had a right of occupancy but not full title, and only the federal government could extinguish their title. This fundamentally limited tribal sovereignty in relation to land ownership.

- Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (1831): The Cherokee Nation sought an injunction to prevent Georgia from extending its laws over their territory. Marshall famously described Native tribes as "domestic dependent nations," establishing a unique trust relationship where the federal government held a fiduciary responsibility to protect tribal lands and resources. However, the Court denied the Cherokee’s direct standing to sue, viewing them as a "state" but not a foreign one.

- Worcester v. Georgia (1832): In a powerful affirmation of tribal sovereignty, the Court ruled that Georgia had no right to impose its laws within Cherokee territory. Marshall declared that the Cherokee Nation was a distinct political community, with its own territory and self-government, and that federal law, not state law, governed relations with tribes. President Andrew Jackson famously defied this ruling, illustrating the persistent gap between legal precedent and political will.

These cases established the core principles of federal Indian law: tribal sovereignty, the federal trust responsibility, and the plenary power of Congress (the idea that Congress holds ultimate authority over Indian affairs, often interpreted as nearly absolute, though challenged over time). While Worcester was a victory for tribal rights, its non-enforcement underscored the vulnerability of Native nations to federal and state encroachment.

The Allotment and Termination Eras: Further Erosion

The late 19th and mid-20th centuries witnessed new strategies to dismantle tribal land bases and assimilate Native peoples. The Dawes Act (General Allotment Act) of 1887, driven by a misguided belief that private land ownership would "civilize" Indigenous people, broke up communally held tribal lands into individual allotments. "Surplus" land, often the most valuable, was then sold off to non-Native settlers. This policy drastically reduced the Native land base by two-thirds, from 150 million acres in 1887 to 48 million acres by 1934, and fragmented tribal communities, creating the complex "checkerboard" land ownership patterns seen on many reservations today, where tribal, individual Native, and non-Native lands intermingle.

The mid-20th century brought the Termination Era (1950s-1960s), a disastrous policy aimed at ending the federal government’s relationship with tribes, abolishing reservations, and dissolving tribal governments. Over 100 tribes were "terminated," losing their federal recognition, land, and treaty rights, leading to severe economic hardship and social disruption. Public Law 280 (1953) further complicated matters by transferring criminal and civil jurisdiction over reservations from the federal government to certain states without tribal consent, eroding tribal sovereignty.

The Modern Era of Litigation and Self-Determination

The Civil Rights Movement and growing Indigenous activism in the 1960s and 70s ushered in the "Self-Determination Era." Tribes, with newfound political leverage and the support of legal aid organizations, began to aggressively use the courts to reclaim lost lands, assert treaty rights, and affirm their inherent sovereignty. This period is where the "map of land claims" truly begins to manifest as a dynamic legal battleground.

-

Oneida Nation v. County of Oneida (1974/1985): This seminal case resurrected the concept of aboriginal title. The Oneida Nation of New York sued for the return of lands taken in violation of the 1790 Nonintercourse Act. The Supreme Court affirmed the tribe’s right to sue for aboriginal title and, in a later ruling, upheld the validity of the Nonintercourse Act in protecting tribal lands. This opened the door for numerous other land claims based on historical violations of federal law.

-

United States v. Washington (1974) – The Boldt Decision: This landmark ruling affirmed the treaty-reserved fishing rights of several Pacific Northwest tribes. Judge George Boldt famously declared that tribes were entitled to 50% of the harvestable fish runs, affirming their "reserved" rights to resources on ceded lands. This case underscored that treaty rights are not "grants" from the government but "reservations" by tribes of rights they always possessed. Similar cases have affirmed hunting, gathering, and water rights, profoundly impacting natural resource management and tribal economies.

-

Water Rights: Often overlooked but critically important, water rights are frequently litigated. The Winters Doctrine (1908) established that when reservations were created, tribes implicitly reserved enough water to make their lands viable. Many ongoing claims involve securing adequate water for tribal agriculture, cultural practices, and economic development, particularly in arid regions of the West.

-

Jurisdiction and Sovereignty: The question of who governs whom on Native lands remains a central legal issue.

- Oliphant v. Suquamish Indian Tribe (1978): This case severely limited tribal criminal jurisdiction, ruling that tribes do not have inherent criminal jurisdiction over non-Indians who commit crimes on reservations. This created a jurisdictional vacuum and contributed to high crime rates in Indian Country.

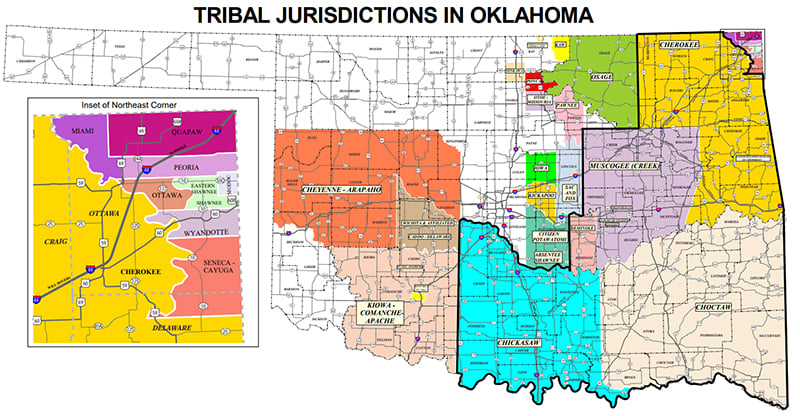

- McGirt v. Oklahoma (2020): A monumental victory for tribal sovereignty, the Supreme Court ruled that a vast portion of eastern Oklahoma, including the city of Tulsa, remains a reservation for purposes of the Major Crimes Act. This decision, impacting the Muscogee (Creek) Nation and subsequently extended to the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, and Seminole Nations, reaffirmed that their reservations were never disestablished by Congress, dramatically expanding tribal jurisdiction over criminal matters involving Native Americans within these areas. This case literally redrew the jurisdictional map of a state.

-

Cobell v. Salazar (2009): This class-action lawsuit, initiated by Elouise Cobell, addressed the federal government’s gross mismanagement of Individual Indian Money (IIM) trust accounts, which held funds from leases and royalties on Native American trust lands. The eventual settlement, totaling $3.4 billion, was the largest government class-action settlement in U.S. history, highlighting the enduring federal trust responsibility and its historical failures.

-

NAGPRA (Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act) (1990): While not a land claim in the traditional sense, NAGPRA has profoundly impacted Indigenous identity and the relationship to land. It requires federal agencies and museums to return Native American human remains, funerary objects, sacred objects, and objects of cultural patrimony to lineal descendants and culturally affiliated Native American tribes. This act acknowledges the deep spiritual and historical connection between Indigenous peoples, their ancestors, and their ancestral lands, even when those lands are no longer under tribal control.

The "Map" as a Layered Reality

The map of Native American land claims is not a simple boundary line; it’s a multi-layered representation of legal, historical, and cultural geographies.

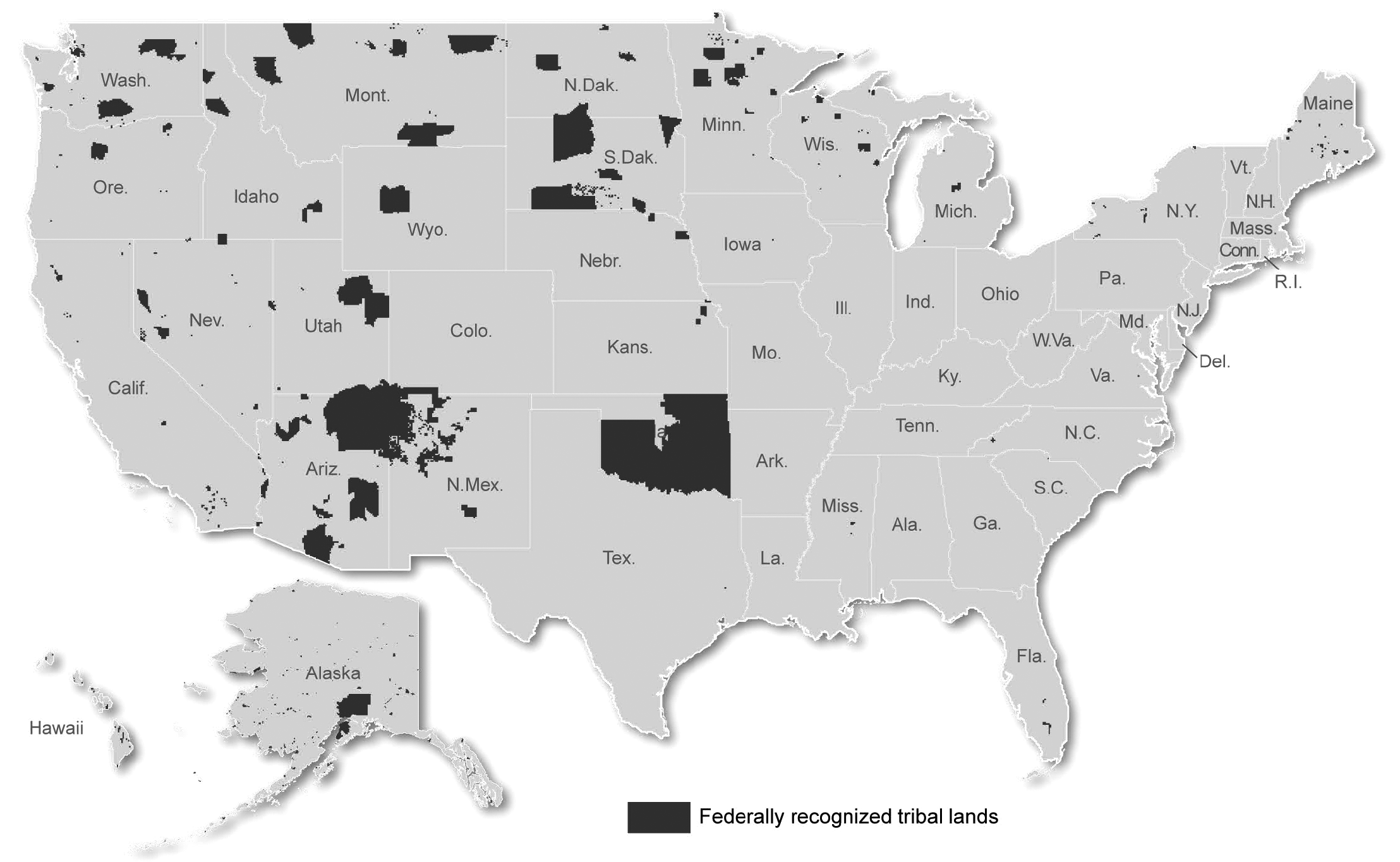

- Reservations: These are lands set aside for the exclusive use and benefit of federally recognized tribes, often held in trust by the U.S. government. However, within many reservations, there are "fee lands" owned by non-Natives or individual Natives in fee simple, creating complex "checkerboard" patterns that complicate jurisdiction and resource management.

- Ceded Territories with Retained Rights: Vast areas of the United States were ceded by tribes through treaties, but often with retained rights to hunt, fish, gather, and access sacred sites. These rights are frequently asserted in court, even on lands now privately owned or managed by states.

- Aboriginal Title Claims: These are claims to lands based on historical occupancy that were never formally extinguished by treaty or statute. While often difficult to win due to legal hurdles, successful aboriginal title claims can lead to monetary compensation or, in rare cases, land return.

- Jurisdictional Boundaries: The McGirt decision vividly illustrates how a "map" can change overnight, not by redrawing lines on paper, but by reasserting long-dormant jurisdictional realities. This impacts everything from law enforcement to environmental regulation.

Identity, Sovereignty, and Resilience

These land claims and legal battles are not merely about real estate; they are fundamentally about identity, sovereignty, and the survival of Native nations.

- Cultural Preservation: Land is inextricably linked to culture, language, and spiritual practices. Securing land and resource rights allows tribes to maintain traditional lifeways, practice ceremonies, and pass on ancestral knowledge.

- Economic Development: Land claims, especially those involving resource rights or gaming, provide crucial economic foundations for tribes, enabling them to fund education, healthcare, infrastructure, and other essential services for their communities, often reversing generations of poverty imposed by federal policies.

- Self-Determination: Every legal victory reinforces tribal sovereignty and the right to self-governance. It empowers tribes to make decisions for their own people and manage their own resources, rather than being subjected to external control.

- Historical Justice: These cases represent a pursuit of historical justice, acknowledging past wrongs and seeking redress for centuries of dispossession and broken promises.

For the Traveler and History Enthusiast

For anyone traveling through North America, understanding the map of Native American land claims court cases transforms a journey into a deeper historical and cultural immersion.

- Respectful Engagement: Recognizing the complex history of land ownership fosters respectful engagement with Indigenous communities. It encourages travelers to understand that the land they traverse often carries a profound Indigenous history, and that many areas remain under tribal jurisdiction or subject to tribal rights.

- Beyond the Stereotype: This knowledge moves beyond simplistic notions of "Indians" or "reservations" to reveal the diverse, dynamic, and resilient nature of over 574 federally recognized tribes, each with its own unique history, culture, and legal relationship with the U.S. government.

- Economic Impact: Visiting tribal businesses, casinos, cultural centers, or national parks co-managed with tribes directly supports Native economies and self-determination efforts.

- Cultural Significance: Understanding the historical context allows for a deeper appreciation of sacred sites, cultural practices, and the ongoing efforts of tribes to protect their heritage. The landscape is not just scenery; it is imbued with stories, legal struggles, and enduring connections.

- Ongoing Relevance: These are not just historical footnotes. Many claims are ongoing, and the repercussions of past decisions continue to shape contemporary Native life. Being aware of this dynamic reality offers a more nuanced and informed perspective on the American story.

In conclusion, the map of Native American land claims court cases is a powerful, evolving document. It illustrates a protracted struggle against injustice, a testament to the legal acumen and unwavering spirit of Indigenous peoples, and a critical lens through which to understand the true history of North America. It demands that we look beyond superficial boundaries and recognize the intricate tapestry of sovereignty, identity, and resilience woven into the very fabric of the land. For the curious traveler and the dedicated student of history, engaging with this map offers an unparalleled opportunity to grasp the enduring legacy of Native nations and their ongoing fight for justice and self-determination.